The forgotten politics of “big tobacco”

It’s worth learning lessons from the wins of the past.

In one of the least-noteworthy policy developments of his first term, Donald Trump signed a law in December of 2019 raising the minimum age to purchase cigarettes and other tobacco products from 18 to 21.

Then in February of 2020, the Trump F.D.A. promulgated new rules restricting the sale of certain kinds of flavored e-cigarettes. Their legal authority to do so stemmed from the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009, which passed the Senate with a strong 79 to 17 vote. That legal authority was used during the Obama years to ban certain previously popular cigarette-marketing terms.

Back when I was a smoker, my brand of choice was Camel Lights, but the F.D.A. — once empowered to regulate cigarettes just like they regulate packaged foods and over-the-counter drugs — decided that was a misleading term designed to convince people that Lights were a healthier alternative to conventional cigarettes. And that is, in fact, how they were marketed in advertising campaigns.

Cigarette advertising used to be a huge deal. Tobacco ads were banned from broadcast TV and radio way back in 1971, and the practical upshot was that cigarette companies became some of the biggest boosters of print periodicals.

Much later, the 1998 Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement between the four largest tobacco companies and 52 state and territory attorneys involved an agreement to stop running cigarette ads in publications that had very large youth-readership shares. Still, when I was an intern at Rolling Stone in 2000, the magazine’s business model relied in large part on the fact that its readership demographics were young-skewing without tripping the T.M.S.A. threshold. And throughout the 2000s, various social-pressure campaigns attempted to shame Rolling Stone and others out of running cigarette ads.

But there’s a reason F.D.A. regulation of tobacco didn’t become law until 2009. The vote was fairly bipartisan; Kay Hagan of North Carolina was the only Democrat who voted no, and most Republicans from outside the South voted yes. But it took Barack Obama winning a landslide presidential election and big Democratic majorities in Congress to make it happen (when Nancy Pelosi passed similar legislation out of the House in 2008, the Bush administration threatened to veto it).

And as Democrats headed into the 2010 midterms looking to boost progressive enthusiasm for what their Congress had achieved despite the crummy labor market, they were a bit surprised and frustrated to learn that the smoking bill didn’t quite have the juice they’d expected, given the issue’s very recent high profile.

On the merits, though, that very nonchalance was the victory.

There had been lots of regulatory blows against the tobacco industry going all the way back to the original 1964 surgeon general’s warning on cigarettes, but for a generation, these were hard-fought wins against a powerful interest group. Obama’s difficulty extracting any juice out of his win signaled that this once-powerful interest was basically dead.

I think it sometimes surprises people who aren’t old enough to remember 1990s and early 2000s politics that these tobacco-regulation topics used to be a top-tier political issue. Thirty years later, it sounds borderline absurd that the Clinton administration was doing major press events about tobacco regulation, and normal people wouldn’t even know how to code this ideologically as a topic in 2025. But it was a huge fight in its day.

When you win on an issue, people tend to stop talking about it. And indeed one lesson of the tobacco fight is that at a certain point, Democrats won on policy but precisely because they won, they stopped being able to make political hay out of it.

It’s worth revisiting these policy successes, both as a source of inspiration and as a reminder that the slow boring of hard boards really can pay off when you’re strategically smart and tactically disciplined.

Big tobacco was a big issue

Michael Mann’s 1999 movie “The Insider” was nominated for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor, but it’s lost to time in a way that his older movies like “Heat” and “Thief” aren’t. Crime dramas are timeless, but the idea that you’d have to penetrate multiple levels of corporate conspiracy to bring people the information that smoking is unhealthy feels odd.

Still, not only was this a mainstream cultural topic at the time (see also John Grisham’s “The Runaway Jury,” which similarly plays as more dated than many of his earlier books), the film is grounded in real world events. By the ‘90s, almost everyone was aware that smoking is bad for you — the surgeon general had been saying so since the ‘60s — but establishing the idea that tobacco companies knowingly deceived the public about the health effects of tobacco was an important part of a larger litigation strategy.

The litigation was important, in part, because one of the main policy goals of the anti-smoking movement was to restrict the marketing of tobacco products. The First Amendment creates significant barriers to regulating this kind of thing, but it was eventually achieved through litigation. In a legal settlement, the defendants normally agree to pay monetary damages to the plaintiffs. But you’re allowed to make whatever kind of deals you want, and the T.M.S.A. included not only money but conduct remedies — including advertising rules that couldn’t be achieved through legislation alone.

Legislation, however, was also difficult.

Republicans were mostly opposed to tougher regulation of cigarette companies, in keeping with their pro-business ideology. But Democrats from tobacco-growing regions of the United States also generally opposed policies they saw as bad for or hostile to local economic interests. The litigation targeted the big cigarette-manufacturing companies, dubbed “big tobacco” by their opponents, in an effort to focus the debate on a small number of corporate actors rather than the much larger set of people involved in growing tobacco.

National Democrats in the ‘90s saw this as a winning political message. Back in 1996, as part of the lead-in to his re-election campaign, Clinton issued an executive order directing the F.D.A. to begin regulating tobacco products. Announcing the initiative, he declared, “Joe Camel and the Marlboro Man will be out of our children’s reach forever.” Journalists who covered the story at the time noted that the F.D.A. would likely lose in court, but Clinton welcomed the political fight.

As predicted, his administration eventually lost in court on this, but that set the stage for the litigation strategy as well as for further political conflict. In 1998, Clinton threw his weight behind a high-profile effort to pass a federal tobacco-regulation bill, and then after the T.M.S.A. came together, he launched a new effort to have the federal government sue tobacco companies. This set up a new conflict with congressional Republicans about funding the litigation effort in 1999 and 2000 that was also dramatized in fictional versions in several “West Wing” episodes. Due to appeals court rulings limiting the actual scope of remedies, this litigation ended up being somewhat anticlimactic when it finally resolved in 2006, but getting it off the ground was a major political fight in the late Clinton era.

The secondhand smoke era

In the 2000 election, this was still very much a live issue.

The Washington Post dedicated an entire article to exploring George W. Bush’s record on tobacco regulation in Texas, identifying some hints of moderation despite extensive ties to the tobacco lobby. The Nation, which at the time was unquestionably the leading left-wing magazine in America, wrote extensively about Bush’s relationship with Philip Morris and published a big tobacco exposé in 2002. Al Gore was accused of hypocrisy for having taken tobacco money as a politician in Tennessee and, in a 2000 op-ed, future Vice President Mike Pence held down the right flank of the debate by arguing that “smoking doesn’t kill.” The 2000 Democratic Party platform had a two-paragraph “fighting teen smoking” plank that mentioned funding federal litigation and legislation to empower the F.D.A. as just two of its policy goals.

But of course, Bush won, so the whole federal agenda ground to a halt.

As the anti-smoking movement shifted to the state and local level, though, anti-smoking activists hit on something that I think was ultimately more consequential than all these pushes around advertising: narrowing the number of places where a person was allowed to smoke.

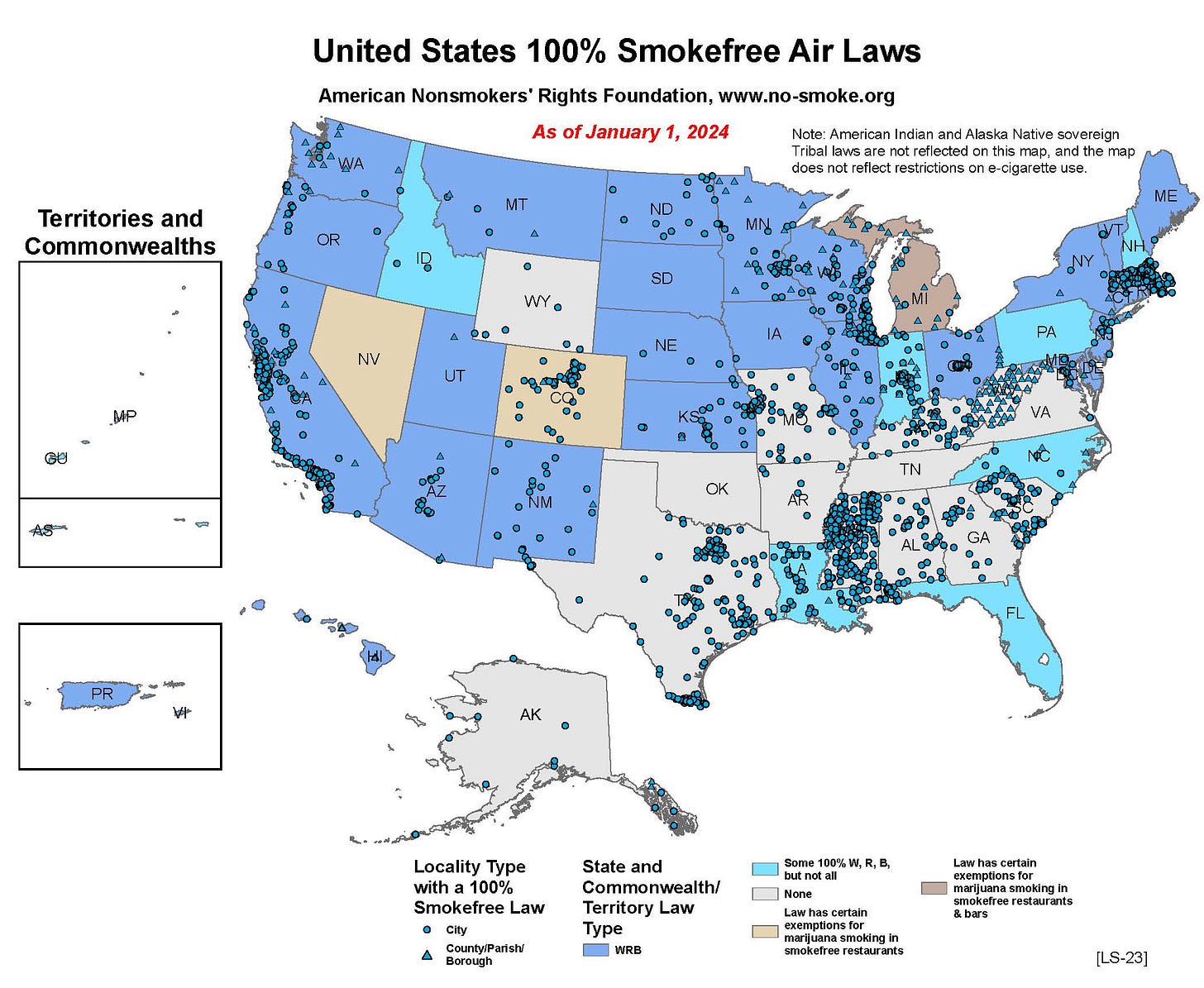

At the turn of the 21st century, you could smoke in bars and independent coffee shops basically anywhere you went. Most chains and many restaurants had gone nonsmoking, but there were plenty of smoking sections available for sit-down diners. When New York City banned smoking in nearly all bars and restaurants while raising cigarette taxes in 2002, it was seen as radical policy change — the public health equivalent of Zohran Mamdani’s government-run grocery stores.

But despite short-term complaining, indoor smoking bans prompted little if any electoral backlash. Once New York City acted, the bans spread like wildfire, taking over most states. Even in a place like Texas, where indoor smoking is formally allowed, more than 100 municipalities (including all the major cities) have anti-smoking regulations in place.

The key is that most people don’t smoke, and most nonsmokers find the smell of cigarette smoke to be pretty unpleasant. Because smokers are addicted to nicotine, there’s a preference intensity gap that makes it rational for a wide range of businesses to cater to smokers, even though most people prefer smoke-free air. That’s especially true when, as was certainly the case 20 years ago, smoking was permitted in almost all bars and many restaurants. But it turned out that the typical nonsmoker, given the opportunity to force smokers to do their smoking outdoors, preferred it that way.

Officially, the point of the campaign against secondhand smoke is that it’s bad for you. Realistically, though, without carefully weighing the cost-benefit analysis of the public health question, you’re just left with the basic fact that cigarette smoke is smelly and most people don’t like it.

Marijuana policy has moved in the opposite direction, but the number one complaint I hear about marijuana legalization isn’t any kind of detailed policy analysis — it’s annoyance that the smell has become ubiquitous in lots of places. Cigarettes as a minor-but-real nuisance proved to be an incredibly potent political argument, and creating a world in which being a nicotine addict is annoying and marginalizing has proven to be a pretty effective way of getting fewer people to smoke.

All of this now-obscure ‘90s and aughts history helps explain why the Obama team was a little taken aback that their historic achievement on F.D.A. regulation wasn’t more widely celebrated. Obama sealed the deal on a major initiative of the prior Democratic president and felt that should count as a huge win. By 2009, the tobacco lobby had lost its grip on Congress, but policy wins by anti-smoking forces had become so routine that nobody really noticed or cared.

The ghosts of big tobacco

This is a lot of words about something nobody cares about, but I think the legacy of tobacco politics lives on in two disparate areas of public policy that people do care about today: MAHA and climate change.

Michael Bloomberg, a pioneer in anti-smoking efforts, was clearly proud of the lives saved by his anti-smoking work. Relatively little of that life-saving impact actually comes from secondhand smoke, but it turned out that secondhand smoke was key to the politics of anti-smoking. And when he wanted to move on to other paternalistic public health causes — banning large sodas and trans fats, for example — he made significantly less progress. Because unlike with cigarettes, there’s no secondhand smoke here. You have to say that you’re taking away people’s Big Gulps for their own good. And progressives largely stopped talking about promoting healthy lifestyles once they realized this kind of thing wasn’t a big winner.

The MAHA movement is obviously about stoking paranoia around vaccines and the pharmaceutical industry. But it’s also about repackaging the paternalists’ basic insights as hierarchical/individualistic right-wing politics rather than egalitarian/collectivist progressive politics. Instead of seeking collective solutions to public health problems, R.F.K. Jr. is pointing to the power of diet and exercise to try to explain why it’s okay to cut food stamps and be indifferent to the need for public provision of health care services.

On the other side of the political aisle, the climate movement has taken direct inspiration from the anti-smoking movement, accusing the fossil fuel industry of using “big tobacco tactics” to cover up the harms of climate change and employing an aggressive litigation strategy when they know the prospects for legislation to ban fossil fuels are bleak.

This analogy doesn’t make a ton of sense. Even though I personally really enjoyed smoking back in the day, the thing about cigarettes is that you can live a smoke-free life just fine. By contrast, we do not have any economically feasible alternatives to fossil fuels for a wide range of socially critical applications, like freight shipping and agriculture. The harms of climate change are very real, but you can’t just wish these technological problems away and act like “big oil” tricked us into thinking that an airplane is a good way to travel long distances. That’s just objectively true.

But in the interest of being nice to the oft-criticized-by-me climate movement, it is smart that they’re at least trying to learn lessons from a successful progressive reform effort.

Joel Wertheimer’s suggestion earlier this week that we use tobacco as a model for thinking about social media regulation is more novel than it ought to be. So much of the discourse around technology regulation has leaned into a narrow antitrust framework or borderline anti-capitalism. Obviously you don’t want to slavishly copy the tactics of the anti-tobacco movement in situations that are different. But it’s helpful to recognize that anti-smoking was a big win and to consider using it as a model for future change.

One important thing to remember is the anti-tobacco movement also went too far. Matt has a line in there about anti-vaping laws as a victory for the movement, but in fact those laws are almost certainly murdering significant numbers of smokers.

Vaping is far less dangerous than smoking and allows people to enjoy nicotine, which Matt concedes is enjoyable. (Full disclosure: I don't smoke or vape.) And yet we apply the same rules against secondhand smoke to public vaping, make vapes difficult to obtain, fill them with warning labels, etc. Why? Because just like Prohibitionists favored putting poison in alcohol, the anti-smoking lobby WANTS to murder smokers because they want to deter people from the fun they disapprove of, rather than focusing on actually saving lives by preventing smoking and chewing tobacco.

This is, I think, a danger in all such movements. They attract puritans, and they don't shut down after winning the important victories. And they can end up losing the thread and lurching towards sociopathy when society doesn't do exactly what they want.

Tangentially, I really, really find flight-shaming to be the absolute lowest and laziest form of performing concern about climate change.

And unfortunately, it's really popular among senior academics who built their career in part on flying to conferences, research sites and collaborations, and then turn around and sanctimoniously tell younger scholars that flying is bad and you shouldn't do it!