The economics of the New Cold War

Competing with China requires more trade, not less

A reminder that you still have one more day to submit questions for Maya’s mailbag on Friday (this one is for paid subscribers).

The United States of America has, without much fanfare, slipped into a version of a New Cold War with China, with the war between Russia and Ukraine serving as a “hot” proxy battle between the two.

You probably don’t think of me as a foreign policy writer, and neither do I. But once upon a time I wrote a book about the Iraq War debate inside the Democratic Party and the urgent need to establish a rules-based international order and avoid a New Cold War dynamic. Then many years later, I wrote a second book accepting rivalry with China as inevitable and calling for a program of domestic renewal and population growth to provide a peaceful path to continued American global leadership. So I actually have thought about this a lot over the years, in a very stepped-back way. I did not stick the landing on timing “One Billion Americans,” because when it came out, a lot of people found the framing puzzling, separate from any points of specific agreement or disagreement.

Now, though, I think people get it.

The current administration differs from Trump’s in many ways, but Biden has maintained Trump-era tariffs on Chinese imports and placed a series of steep new tariffs on Chinese electric cars, prioritizing strategic competition over short-term emission reduction. Congress’ moves on TikTok, similarly, are a complete repudiation of Clinton-era optimism about commercial ties leading to Chinese political liberalization. Today we are concerned, appropriately, about the opposite dynamic — that commercial ties will allow China to export its own authoritarianism around the world. When people eventually look back in a more sober-minded way, I think they’re going to see not only that Biden’s approach has had a lot of continuity with Trump’s, but that Obama pivoted pretty hard away from engagement in his second term.

That being said, I always thought that if a New Cold War broke out, there would be some kind of grand declaration, that everyone would say “here’s the day it happened, now the New Cold War is on.” In retrospect, I don’t know why I thought it would happen that way — why shouldn’t things unfold gradually? But because there was no dramatic declaration, I think the general public doesn’t fully grasp the significance of the situation we are in. Notably:

Intense geopolitical competition with China is a huge bummer that is going to leave people worse off than we’d be in a more cooperative world.

The United States (and friends) are at very serious risk of losing to China (and friends) unless we start making smarter choices.

Making smarter choices is going to have to involve both some level of greater bipartisanship at home and more coordination with the “(and friends)” abroad, which seems hard to pull off, on both counts.

Foreign policy is much more driven by elite consensus than by public opinion, which does make cooperation easier to imagine here than on many issues. But it also intersects with climate change, labor union interests, taxes, and other matters that are of concern to the general public. So an elite consensus around China can’t just be a consensus among foreign policy elites — the situation requires an approach with some level of public buy-in.

We’re not number one

To some extent, obviously, Biden’s latest tariff gambit is primarily about Trump and the Electoral College. But I think cynics have downplayed the force of the argument on the merits.

China, for better or worse, is continuing to grow its manufacturing exports, even as overall economic growth has slowed down dramatically. The United States would like China to seek future growth by producing more services for domestic consumption — for example, providing its citizens with more robust health care and pension benefits — but the Chinese government is choosing not to do that, instead throwing everything it can into making more goods. China’s overall GDP is either slightly smaller than America’s (at market exchange rates) or slightly higher (using Purchasing Power Parities), but its manufacturing capacity is much larger than ours.

If it comes to a war, this is no bueno. It’s nice that American companies dominate the global market for streaming video and targeted web ads, but it’s hard to convert the production of tradable services into military might. By contrast, if you can build cars, you can probably pivot to building military vehicles; that’s how our grandparents won World War II. Now obviously, the United States could cede the entire civilian automobile value chain to China and just try to preserve a separate tank industry. But in practice, your defense industrial base is likely to become extremely uncompetitive and unproductive if it’s not sharing any supply elements with civilian production. If we're going to need microchips and metal and whatever else for military production, we also want to have civilian manufacturers using many of the same components to make products that are competitive on global markets.

Slapping prohibitively high tariffs on Chinese electric cars and key components like batteries is a pretty crude policy approach, especially absent good complementary measures. But it does make sense.

A different world

I am a believer in the economic benefits of free trade. If history were going in a different direction, I would have a different view of this.

Imagine the past decade or so had gone in a different direction.

Specifically, imagine the 2014 Umbrella Revolution in Hong Kong had succeeded and entrenched the principle of “one country, two systems,” with a liberal and democratic Hong Kong operating in association with the larger People’s Republic of China. And then say Xi Jinping announced a successor in 2018 rather than announcing the end of term limits for Chinese leadership. In our world, Trump grandly announced that he’d secured a huge deal with China on trade, but in reality they never implemented it. In the Happy Timeline, Chinese leaders see that the thing American officials want them to do — raise domestic consumption — will also be popular at home, so they actually do it. Xi’s successor takes over a few years later and says explicitly that he’s glad the Umbrella Revolution succeeded, because it’s important to show the people of Taiwan that peaceful integration can happen, and as a step in that direction, they are going to start liberalizing speech controls at home. This China is proud of ByteDance’s global success, and wants to prove to the world that it can trust Chinese companies, so it orders everyone to stop trying to export Chinese censorship.

That world is not all roses. But it’s a world in which engagement is working and the dream of the nineties is alive.

In that world, I would say that if China wanted to export cheap electric cars to everyone, that’s great. I would say it’s natural in some respects for global manufacturing’s center of gravity to be in Asia, since that’s where most people are.1 Specifically, the center of gravity should, in fact, be in China, with important penumbras and emanations fanning out to Korea and Japan and down to Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Then the United States really could just specialize in natural resources and internet companies, while Europe does tourism and niche luxury products. The logic of comparative advantage is powerful.

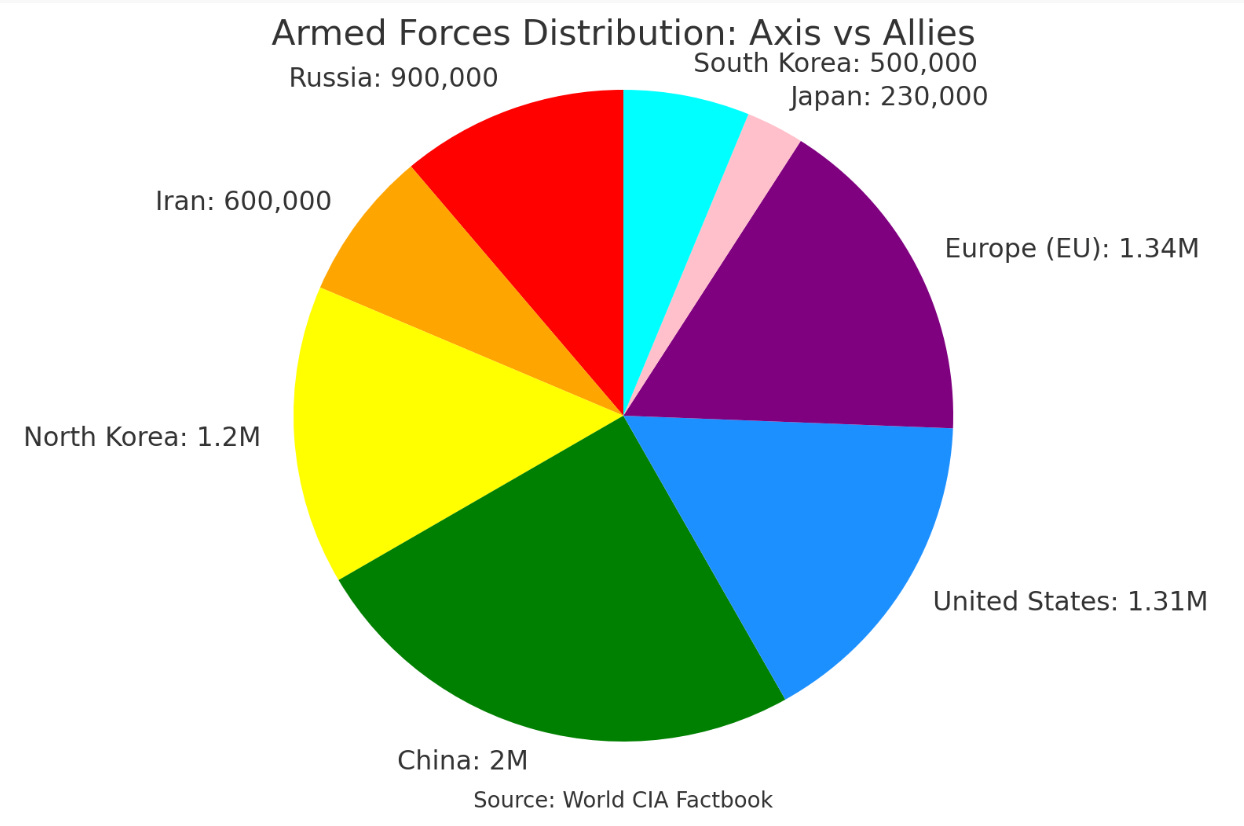

But we are pretty clearly not in that world. The actually existing People’s Republic of China has quashed all hope of domestic liberalization, clearly aspires to coercively reunify with Taiwan, and tries very aggressively to control what people outside of China can say or do about their country. And I think it’s dangerous for a country like that to dominate global manufacturing. Right now, the good news is that if you combine the United States with our major allies among the other advanced industrial democracies, the New Allies still out-manufacture the New Axis of Russia and China. But there are plenty of crucial sectors, including not-so-minor items like warships, where we have the smaller half of the stick.

This is not a great situation. What’s more, Iran and North Korea have giant militaries for relatively modest sized countries, while Japan has a small military despite being a large country. Obviously a raw count of the number of people in uniform is not the most precise indicator in the world. But it’s a sign, like the warships, that the balance of power is not necessarily in favor of the forces of freedom and democracy.

All of which is to say that we should not be complacent about the current situation. We really do need to be building more linkages and deeper ties with friendly countries to help the entire free world grow as much as possible.

Strategic competition, not protection

Twenty years ago, I worked at the American Prospect, which was always close to labor unions and skeptical of free trade. Some of the folks there were very big on the work of the US–China Economic and Security Review Commission, including its many reports on the dangers of letting too much of the US industrial base migrate to China. They liked this argument, of course, because they were always looking for rationalizations for protectionism. I used to say “watch out, this is actually just crazy China hawks.” And now that I’m a China hawk, it drives me crazy that there is still muddying of the waters between the argument that there is, in fact, a specific national security issue with China and generic revisionist theories of trade economics.

But I think it’s important to say that 100 percent of the economic arguments for free trade apply completely in a world of intensifying geopolitical competition. My argument is that, for geopolitical reasons, we should do something that is economically costly. Building an aircraft carrier “creates jobs,” but it’s not something that you do for economic reasons. Judged in purely economic terms, aircraft carriers and missile silos and nuclear attack submarines are all just giant wastes of labor and material. Just because it’s economically harmful to maintain a powerful military doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it. But you also shouldn’t delude yourself into thinking it isn’t economically harmful.

By the same token, trade barriers with China are economically costly.

What we ought to be doing is trying to minimize the total amount of trade barriers, and thus the economic cost of pursuing competition with China, by reducing as many trade barriers as we can. We should stop complaining about cheap Canadian lumber. We should stop blocking imports of Latin American sugar. We should let Toyota sell cheap small trucks to Americans who want them. We should, frankly, probably start buying (or leasing2) warships from Japan and Korea, where they actually know how to build ships. America is toast in a conflict with China if we can’t count on cooperation with our friends, so we may as well optimize on maximum economic efficiency and the freest possible trade within the free world. This also applies to quasi-trade in professional services — we should make it easier for foreign doctors to practice here, and have the FDA and European drug regulators work together so approval by one agency will let you sell on either side of the Atlantic. There’s a lot we can do to work together internationally and increase prosperity.

But of course, I wouldn’t be me if I didn’t insist on the relevance of the domestic piece of this. Right now, American politics is being torn apart by the edge case question of how to deal with floods of people making asylum claims. But the historical foundation of America’s emergence as a great power was the deliberate cultivation of a large population via legal immigration. There is so much the United States could do to boost our domestic production capabilities by legalizing more housing growth and more immigration of skilled workers. On both fronts, though, I worry that the country has gotten mired in some slightly odd fantasies of autarky, where we try to have entire supply chains fully within our borders, even while the labor force shrinks. That doesn’t make any sense, and in an increasingly competitive world, we don’t have the luxury of indulging in nonsense.

If you draw a triangle between Indonesia, Pakistan, and Japan, that contains the majority of the world’s population.

When a company buys something expensive and durable, the normal practice is to say that at the time of purchase, you just swapped money for an asset with no impact on the balance sheet, and then the “cost” plays out over time as the thing you bought depreciates. The government just accounts the full cost on the day the thing is bought and doesn’t consider the value of the asset. This makes the up-front outlay involved in acquiring ships look prohibitive. So theoretically, you could lease them instead and spread the cost over the useful life of the ship.

I agree we’re in a second Cold War. But I think it’s not just with China, and it’s important to underline that.

I also think it’s pretty clear when that second Cold War began: February 24, 2022.

The Ukraine war made it official: We’re not going back. Regimes like Russia and China are not just going to try to oppose Western-aligned regimes, but discredit, neuter, and render democracy a dead letter where it lives—and where they do not accept it, physically crush it. China and company clearly regard all that as critical for their own regimes’ survival.

Qua Anne Applebaum, I think the dictators of the 21st century have found each other and realized their common interests, and what stands in the way of their common interests. And also qua Anne, I think that second Cold War is being very clearly fought at home, in a way the first never was, no matter what Joe McCarthy pretended.

A MAGA victory, and the return to power of a lawless indicted criminal in the United States, is China, Russia, and the whole corrupt gang’s dearest hope for victory, and for their enemies to go the way of the USSR circa 1991.

(Trump himself would probably agree, in a way—he seems to regard China’s model for governance with more admiration than America’s. If they just stopped calling themselves “communist” they wouldn’t be so bad, in his mind.)

To an extent MAGA ideas seem aimed at unwittingly losing the second Cold War, that may not be a coincidence. The MAGA foreign policy vision, if you can call it that, seems aimed not so much as bringing about “peace” as re-directing our martial energies away from engaging in world affairs, and toward crushing its domestic opposition at home. To them, Russia, China, authoritarianism writ large are nothing compared to the “threat” of the people in their own country they don’t like. All their boasting about their anti-China bonafides to the contrary, it’s a literally, and almost openly, anti-American message.

We may have to start acting, and politically treating them, accordingly. It will be difficult to align the fractious liberal coalition behind such a counterintuitive, “patriotic” platform. I don’t know that liberals can unite for any reason at this point, let alone for that one. But I think they’ll ultimately have no choice.

The good news is this issue is genuinely getting traction, and throughout the Biden administration you've clearly seen bipartisan elite support moving in the right direction. The bad news is the American public has become more distinctly isolationist. I don't think there's public enthusiasm yet for going to bat for allies (or even for Taiwan) over Chinese aims in the Pacific. There needs to be a very distinct threat directly at American interests to galvanize support.

This all feels very sadly 1930s. The New Axis is armed to the teeth and on a roll, the New Allies are dawdling, with American elites trying to quietly start moving America back to war footing while the public, disillusioned by some foreign escapades about 20 years ago, wants nothing to do with playing a role in the global order. We might need a kick in the pants, but if Pearl Harbor happened now we'd be in trouble. By 1941 we were fully rearmed and in wartime production, or ready to be in months.

And I've said it elsewhere, but it is genuinely tragic that China is heading in the direction of is. The integration of a billion Chinese into the liberal order would have been outstanding. Look at the cultural footprint of the Asian powers that entered the order - batting way above replacement. The Chinese diaspora has made a huge positive impact here in the US. Nothing is set in stone, and things can still work out for the best. But it's not looking great right now.