The declining significance of race, quantified

New research updates a classic

Raj Chetty and his colleagues at the Opportunity Insights project have been producing papers detailing new research on upward mobility for years now. Their latest effort, co-authored by Chetty with Will Dobbie, Benjamin Goldman, Sonya R. Porter, and Crystal S. Yang provides a granular and persuasive look at a phenomenon that I think most people are aware of but that isn’t discussed as much as it should be: the waning of the racial caste system in America, and its replacement by a growing level of economic stratification.

At the beginning of the year, I wrote about William Julius Wilson, the great sociologist of race and class, whose 1978 book “The Declining Significance of Race” anticipated a lot of what this latest Opportunity Insights paper finds (back in his “Hillbilly Elegy” phase, J.D. Vance was very much writing about these themes as well — they even did a panel together). The paper has lots of detail and plenty of nuance, but the basic story is captured in the chart below, which shows the relationship between an individual’s income and parental income, at age 27, for people born in 1978 and for people born in 1992, separated by race.

What you see is that for white kids, the slope of the line has gotten steeper — meaning the poor are more likely to stay poor and the rich are more likely to stay rich.

For Black kids, though, the line retained a similar shape and just moved up.

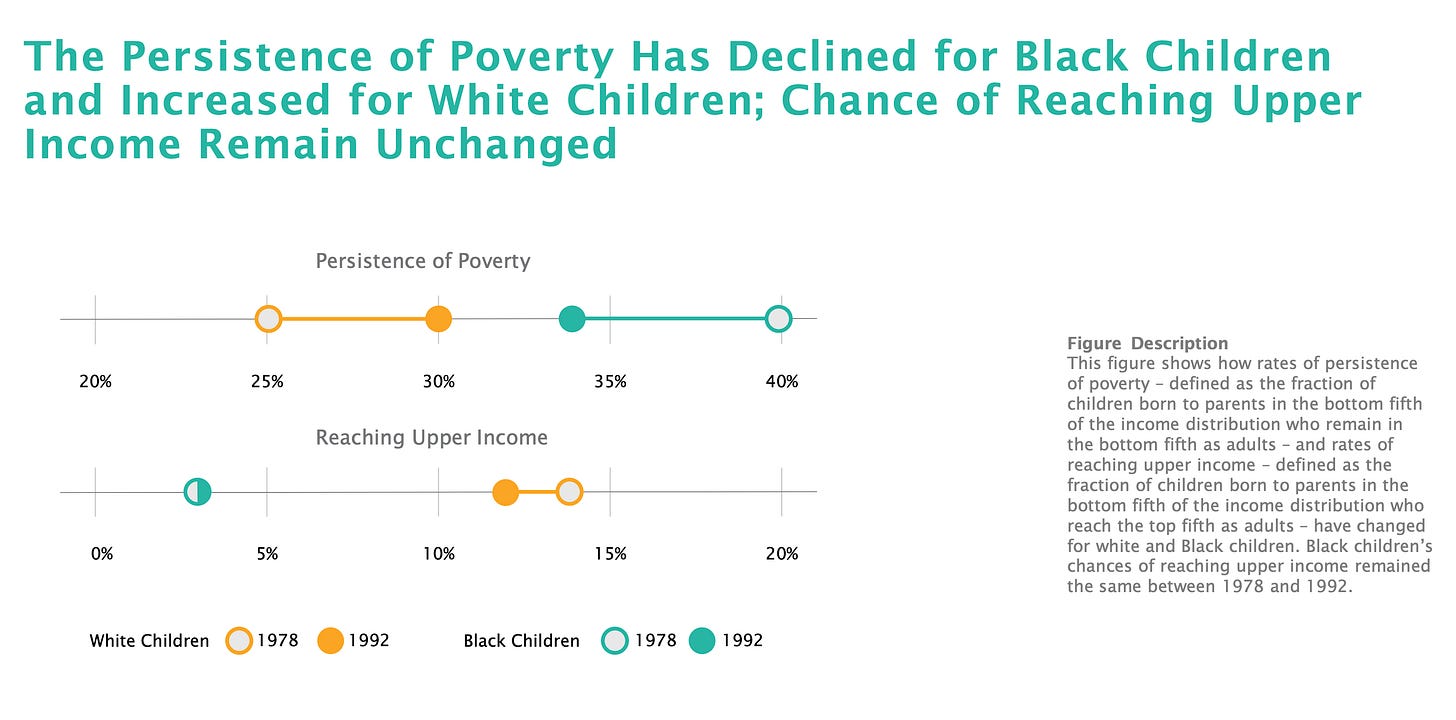

This is to say that though African-Americans at all parental income levels today enjoy less upward mobility than similarly situated white kids, they are more likely to experience upward mobility than similarly situated Black kids born 14 years earlier. The purely racial opportunity gap is narrowing, which is good. But it’s getting especially narrow at the low end of the spectrum, because upward mobility for poor white kids is getting worse. A related visualization shows that poverty has become more persistent for white kids, but less persistent for Black kids, while poor white kids’ odds of making it to the top fifth of the income distribution have declined and Black kids’ odds remain low.

They have some theories about why upward mobility varies from place to place and how we might be able to leverage that to generate more upward mobility. But I do think that the descriptive sociological facts are worth dwelling on, because they touch on some delicate but politically significant issues.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.