The dangerous war on Tylenol

Autism diagnoses have increased because diagnostic practices changed.

I spoke with someone earlier this week who is optimistic that the Trump administration is going to reform the clinical trial process in ways that should make it cheaper and easier to get safe and effective medications to market.

This is a really good and important idea, one I’ve been talking about for years. I’ve written about challenge trials for vaccines (and noted larger problems with the regulation of clinical research) and about the importance of boosting drug innovation on the supply side, not just the demand side.

Rapid progress in artificial intelligence makes this all the more pressing, because it seems likely that A.I. is going to give us some speedier ways to identify promising candidate molecules and potentially to gain more insights into safety and efficacy, but without per se speeding up the regulatory process. I’m worried about a biomedical equivalent of the elevator, where we have developed a great technological solution to the problem of land scarcity (tall buildings) but in America, we mostly don’t use it.

I hope Trump finds his way toward some bipartisan reforms here. He certainly has some biotech innovators in his corner pushing in that direction.

On the other hand, the president just did a splashy press conference with his secretary of health and human services in which he told pregnant women they should stop taking Tylenol because it’s causing autism.

This was all, in some sense, harm reduction relative to the possibility that the Trump administration might move to more decisively embrace the theory that measles vaccines are causing autism. And the good news is that acetaminophen remains on the market and fully available in pharmacies. So biotech-oriented people can certainly tell themselves that Trump remains a force for good on the regulatory front.

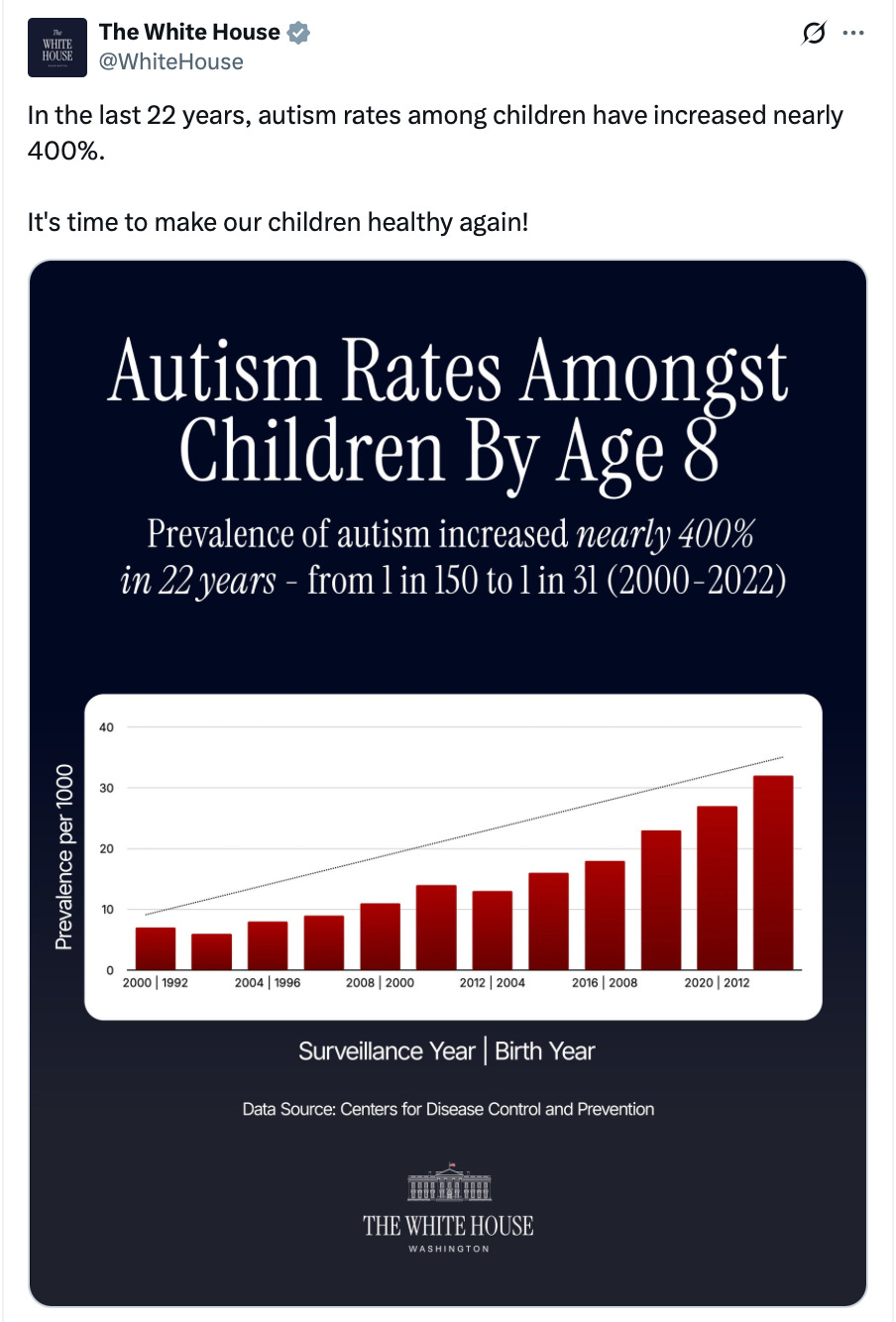

But I do have to say, I think it’s dangerous to have the White House and H.H.S. controlled by people with terrible epistemics, the kind of people who put out this kind of public message:

The research considering a Tylenol-autism link is not as shoddy as the vaccine-autism theory, and the consequences of stigmatizing Tylenol use are not as dire as stigmatizing vaccines. However, the causal research on this is still pretty flimsy. Studies with better causal design, such as those that rely on sibling controls, find no association.

The bigger point that I would make, though, is that it’s unclear whether there has been any rise in autism at all. There are certainly more diagnoses. But that’s almost certainly because the diagnostic criteria have changed, there’s more surveillance, and there are shifting incentives for families and institutions to diagnose more cases.

I don’t think that necessarily means that the rise in diagnoses is entirely benign. There are reasonable questions to ask about whether more aggressive diagnosis of psychological maladies is making things better or worse.

But serious people would be asking serious questions, not promulgating nonsense.

From “infantile autism” to “autism spectrum disorder”

If you’re looking to explain why something increased four-fold between 1992 and 2012, your proposed cause should probably also be something that increased dramatically between 1992 and 2012.

If the M.M.R. vaccine had been introduced in 1992 and phased-in steadily over the next twenty years, that might be an interesting hypothesis to investigate. But it was developed in 1971, and nothing about it changed in the 1990s. Similarly, acetaminophen has been the preferred option to reduce pain and relieve fever in pregnant women for more than forty years. If we’re trying to understand a more recent change, we need to look at potential causes that changed more recently.

And what’s changed dramatically is diagnostic practice.

The terminology of autism as a distinct syndrome dates back to Leo Kanner’s 1943 article “Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact” in which he argued that a particular set of behaviors should be acknowledged as something other than schizophrenia. This proposed shift was debated in the literature for decades, and infantile autism was not officially recognized by the American Psychiatric Association until the publication of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1980.

The D.S.M.-III called for a diagnosis of infantile autism if all six of these criteria were met:

Onset before 30 months of age

Pervasive lack of responsiveness to other people

Gross deficits in language development

Peculiar speech patterns (if speech is present) such as immediate and delayed echolalia, metaphorical language, or pronominal reversal

Bizarre responses to various aspects of the environment, e.g., resistance to change, peculiar interest in or attachments to animate or inanimate objects

Absence of delusions, hallucinations, loosening of associations, and incoherence, as in schizophrenia

This is clearly describing a uniformly debilitating condition, especially in terms of criteria (3) and (4). But in 1987, the diagnostic criteria were updated, notably altering the speech criteria to “qualitative impairment in verbal and nonverbal communication and in imaginative activity,” such that someone might qualify by failing to make eye contact and “indulging in lengthy monologues on one subject regardless of interjections from others.” The ’87 criteria were still quite strict, but this marks the commencement of a shift in autism diagnosis from applying exclusively to people with severe functional impairment to including behaviors that are sometimes present in people who are quite functional.

By the time the D.S.M.-IV came out in 1994, things like “lack of social or emotional reciprocity” when combined with “lack of varied spontaneous make-believe play or social imitative play appropriate to developmental level” could qualify a child for an autism diagnosis, as long as they also have trouble making eye contact.

At this point, a pretty big range of behaviors could qualify.

And because we’re talking about diagnosing kids, we’re talking about a pretty big range of potential long-term outcomes. Back in the 1940s, at around the time Kanner first published on autism, Hans Asperger wrote a study of what he called “autistic psychopathy,” which involved children (mostly boys) whom he characterized as suffering from behavioral and social deficits but who were also “little professors” who could talk with adults in great detail about their subjects of special interest.

Clinicians came to see a relationship between these kids and Kanner’s kids and to conceptualize the issue at hand as a spectrum of behaviors that ranged from people experiencing profound difficulties to people who are just eccentric. The D.S.M.-IV characterized a separate-but-related Asperger’s disorder, and then the 2013 D.S.M.-5 shifted to a unified autism spectrum disorder (A.S.D.) that includes an expansive range of behaviors.

And this, not Tylenol usage or vaccines, is the big thing that shifted rapidly during the time period in which we see an enormous increase in autism diagnoses.

Autism detection has become more intense

Something that I think is often missed here is that small changes in classification can have disproportionately large impacts on counts. Suppose you say that you need to have a 1450 SAT score to be “smart.” That’s about 1 percent of test-takers.

If you relax it to 1300, then 9 percent of test-takers are smart. And if you drop 150 points more down to 1150, then 26 percent of test-takers are smart. I don’t think there’s any objective way to decide whether we should say that a quarter of people are “smart,” or 10 percent or 1 percent. These are all viable definitions of smart. But because SAT scores are normally distributed, each 150 point drop from perfection brings in a larger group of people than the prior one. By the same token, shifting from “gross deficits in language development” to Asperger’s “little professors,” generate a much larger group of people with autism.

At least, if anyone is bothering to count.

The more people discuss autism, the more people seek diagnoses. The rise in childhood autism has corresponded with a fall in the number of other childhood intellectual disorders. Some states have adopted rules mandating insurance coverage of A.S.D., which studies show leads to more A.S.D. diagnoses over time. It’s widely believed that early detection and treatment can lead to better outcomes for kids, so a number of states have incentivized early screening in schools, which studies show leads to more diagnoses.

One can read trends in an idealistic or cynical manner. Idealistically, we’re trying harder to identify kids in need and delivering them helpful resources. Cynically, we’ve created financial incentives to classify borderline cases as A.S.D. to unlock money.

The truth is probably some mix of the two.

With autism, there’s no blood test that can verify ground truth or a cheap and highly effective treatment that can be used in cost-benefit analysis. There are lots of kids in the country who benefit from additional resources for all kinds of reasons. One study in California found that 26 percent of the increase in A.S.D. cases was accounted for by a reclassification of what would previously have been diagnosed as generic “mental retardation.” Pediatricians are now told to do universal A.S.D. screenings during well-child visits. The Affordable Care Act mandated that insurance plans make well-child visits free and explicitly identifies A.S.D. screenings as covered services.

I do wish I could offer you a take on the merits of the increased screening and changed diagnostic criteria. Is this helping a lot of people? Is it mostly just shifting resources within the child development space around? I haven’t been able to find credible analyses on these questions. But I do think the facts are pretty clear: We have simultaneously adopted more elastic criteria for who counts as autistic and also tried harder to positively identify cases. So of course we get more cases. The interesting question is how helpful this has been.

A cascade of harmful information

Autism has become highly politicized, but if you’ve tuned in at all to American society over the past few decades, you’ll recognize this as part of a broader trend of more awareness of various mental health conditions and more tendency to apply mental health terminology broadly.

People who are not in fact suffering major impairments in their lives will describe themselves as “O.C.D.” or “A.D.H.D.” to broadly express aspects of their personality. I have a weird thing where if I can help it, I like to avoid retracing my path through the city. Because D.C. has a grid-type street layout, there are normally a large number of roughly equivalent routes I can take between Point A and Point B, so I’ll take one route going and another returning. I try to apply this in the Maine countryside, where I live during the summer, even though it’s less convenient.

But in terms of practical impact on my life, this is closer to the “weird quirk” end of the spectrum than to the “debilitating compulsion” end. If looping is significantly less convenient than backtracking, I’ll just backtrack. But back during Covid, when I was routinely taking my kid out on Saturday hikes, I did spend a non-trivial amount of time trying to make sure I could find loop trails rather than out-and-backs. And because we live in an era of mental health awareness and destigmatization, I do tend to talk about this — to the extent that I talk about it at all — using the language of compulsion.

The question of whether this mental health awareness trend has gone too far is an interesting one. But wherever we draw the line for a particular diagnosis, a lot of people will be just on the other side of the line and some will feel that the line should be moved as a matter of logic. And whether that’s actually true is in part a question of whether there are helpful treatments.

But there are also society-level implications. Getting an I.E.P. for a child can unlock additional resources for that kid in a way that’s helpful, but it does not magically generate additional resources in the world. Expansive criteria can crowd out help for those who are most in need or best-positioned to benefit. The clinician’s instinct that it’s always better to diagnose is good if there are highly effective treatments available at low marginal cost, but that’s not always the case. I think there are legitimate questions in this neighborhood that an H.H.S. secretary who knows what he’s talking about could be asking.

But speaking of conditions for which effective low-cost treatments are available, acetaminophen works really well at reducing fevers.

We also know that, while fever can be very uncomfortable, fever per se is not normally a big health problem. The big exception to this is pregnancy, when elevated body temperature increases the risk your baby will develop spina bifida. Pregnant women are advised to avoid saunas and hot tubs for the same reason. Telling pregnant women to “tough it out” during a spell of fever is genuinely terrible advice.

To return to where I started, Trump isn’t big on intellectual rigor or consistency, so it’s certainly possible that he’ll accelerate new medical developments even while talking total nonsense about the subject. But his abandonment of his own major achievements on vaccine development should raise doubts here. It’s hard to spur biomedical advances when you surround yourself with kooks and cultivate a political constituency of cranks.

It does seem kind of ridiculous that someone who can't speak and needs 24/7 care is said to have the same "disease" as someone with a large Lego collection.

Half this comment section at least, myself included, would have formal autism diagnoses had we been born 15 years later.