The case for progressive austerity

Lower inflation and lower interest rates can be achieved.

Today is Day One of a two-week break from public school during which time we have two major federal holidays that will occur on Thursdays. Slow Boring is committed to keeping everyone entertained and informed during the holiday season, but with a somewhat reduced pace of work activity from our staff. So there will be no posts on Christmas Day or New Year’s Day, the comment section is going to be more lightly moderated than usual (but behave yourselves because if people have to take time away from their families to intervene it’ll probably be by bringing the hammer down), and all our posts are going to be for paid subscribers only and a little bit more off the news than usual.

Hope everyone has a Merry Christmas or an enjoyable observance of the War on Christmas according to your personal tastes and family traditions.

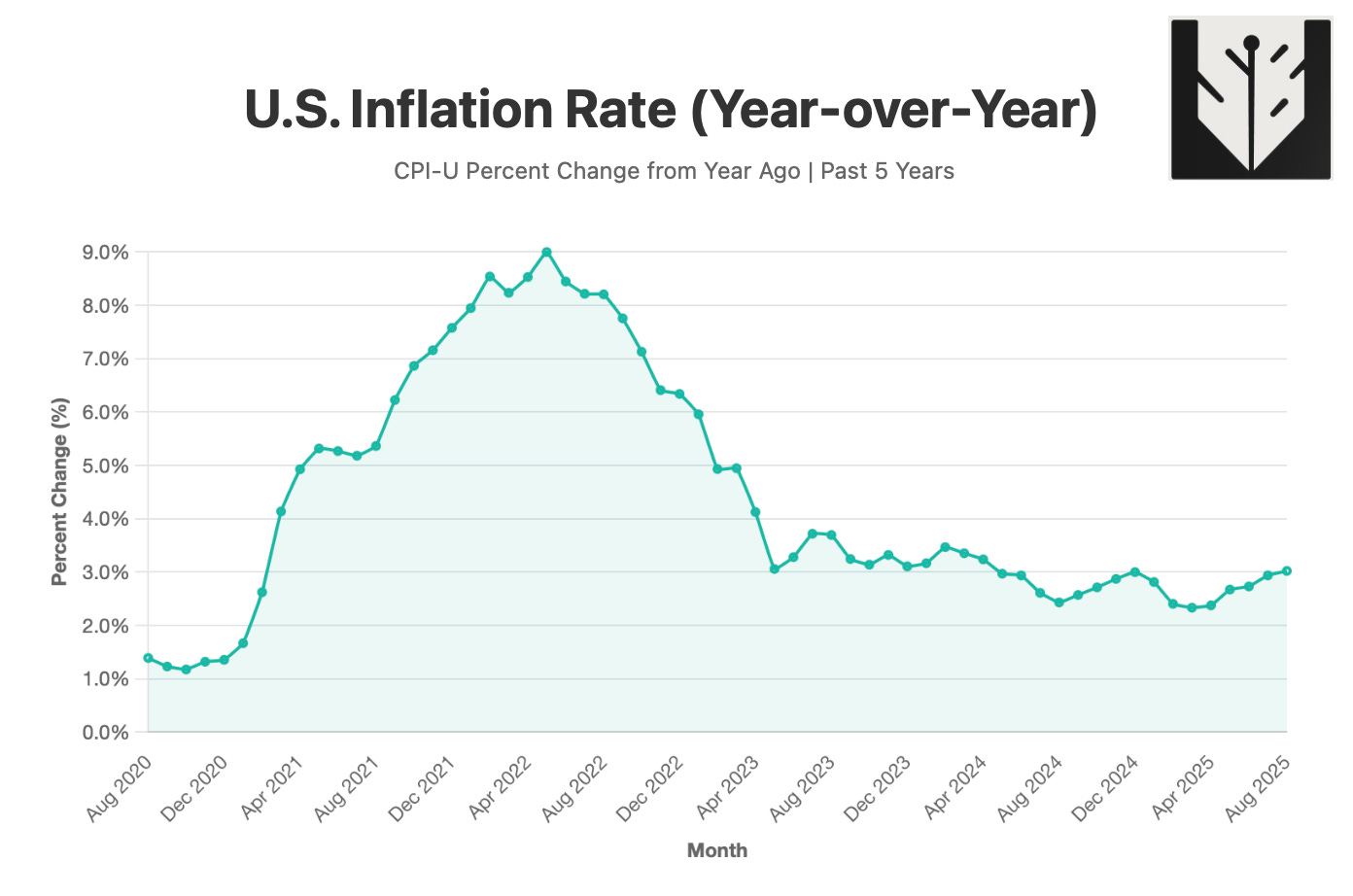

Inflation was very high in 2021 and 2022, and while it was definitely lower and falling in 2023 and 2024, it didn’t go all the way back down to the Fed’s target rate of 2 percent. Then in 2025, inflation stayed above target and if anything picked up a little.

Given how central inflation was to the politics of the Biden era, I think this basic set of facts has received too little attention.

Democrats have decided that talking about “affordability” is better than talking about “inflation,” which is fine by me. But this has spun out in ways that are slightly odd, with progressives both overthinking the true meaning of the cost-of-living crisis (as in this Roosevelt Institute report) and also underthinking the boring question of what Democrats are prepared to do on policy to generate lower inflation.

And I want to be clear that I’m talking about a governance problem more than a messaging one.

The mass public’s understanding of macroeconomic issues is poor, so plenty of things that sound persuasive to voters won’t work and vice versa. How to cope with that is a hard question. But to answer it, Democrats need to start with what would actually work to bring inflation down. This isn’t a huge mystery that requires us to reinvent the wheel in terms of public policy. The Federal Reserve could run tighter monetary policy, but that has a lot of well-known downsides. Or, we could lower the budget deficit.

“We should reduce the budget deficit” is not an alien concept in Democratic Party politics. Bill Clinton did it. Barack Obama’s administration emphasized deficit reduction, though at a time when it was macroeconomically inappropriate. Joe Biden ran a unique experiment in dropping this from the Democratic Party lexicon, and it didn’t work out very well.

Of course how to reduce the deficit is controversial. But there are plenty of deficit-reducing ideas with solid progressive backing.

The hard turn is that Democrats would have to commit themselves to actually deploying these ideas for the purposes of deficit reduction rather than using all the revenue on new spending. That kind of restraint is a tough pill to swallow for many in the post-Obama party, which I understand.

But there isn’t really that much to the “affordability” issue other than trying to make inflation and interest rates lower, so it’s worth taking seriously. Maybe there will be a recession or a war or something else that knocks this off the agenda. But as long as the cost of living is the number one issue on voters’ minds, it’s smart to think about actually workable ideas for addressing it.

How Trump built himself a pain cave

When Donald Trump was campaigning in 2024, he promised over and over again, and explicitly, that if he were elected president, he would make the price level drop, reversing the inflation that occurred during Joe Biden’s presidency.

This is what voters wanted to hear, so it made a certain amount of sense to promise it, even though informed people knew he couldn’t possibly deliver.

The cult-like structure of MAGA politics also helped him here. The question of whether engineering a fall in the aggregate price level would be feasible or desirable is not one that separates conservatives from progressives — it separates an informed minority from a not-informed majority. A Democrat who centered a promise this ridiculous would face elite friendly fire in the media, which would encourage some same party elected officials to defect, and next thing you know you have a circular firing squad.

But if Trump wants to run around the country promising an immediate drop in the price level, nobody is going to take up space in conservative media contradicting him.

What happens after the election? Well, that’s a problem for after the election.

But I have to say that I thought it was going to work. My guess was that if Trump won the election, conservative media would start cheerleading for the economy and a lot of independents would sort of mentally reset and say inflation was a Biden problem. I was actually pretty confident about this, in retrospect overconfident.

What we know about inflation is that historically it has been brought to an end by a recession. For that reason, if you go back to 2022, you can find a lot of analysts who are confident that only a big spike in unemployment will bring inflation back down.

I said at the time that I thought that was wrong, but I had to concede that I was making a purely theoretical argument. Empirically speaking, past inflations were ended by a recession. We also know that when a recession hits, jobs and the recession become the top issue. We had no information about how public opinion would react to inflation slowing down; I just kind of assumed that if Trump, he would reset people’s intuitions and do okay.

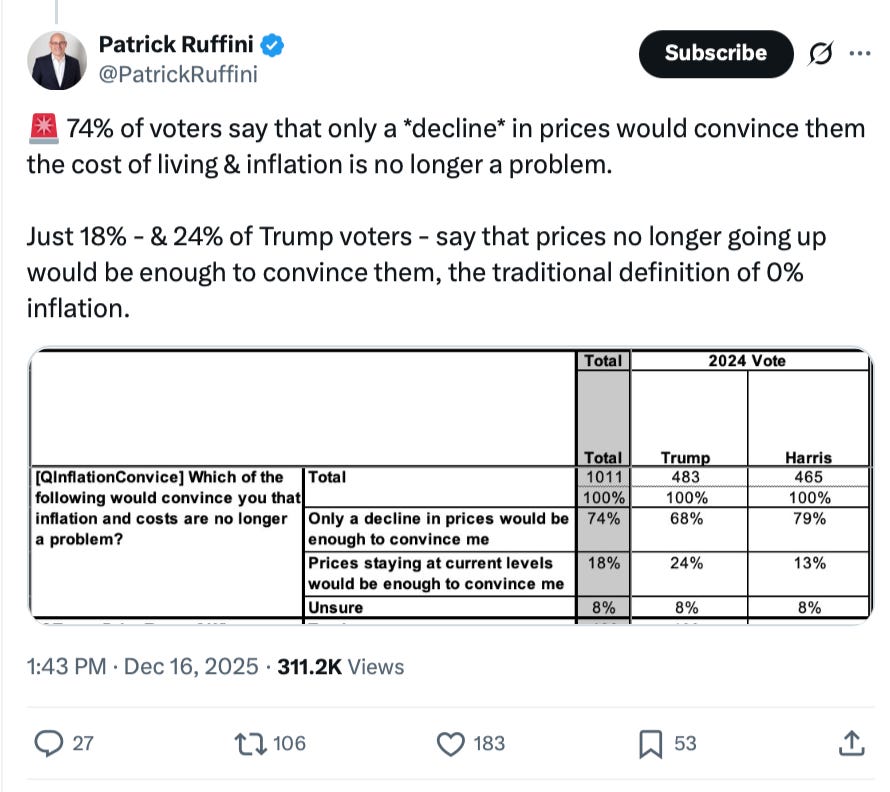

And I guess he made the same bet, but it’s worked out very poorly for him because voters — including a huge share of his supporters — say that they genuinely want falling prices.

I feel like I’ve spent a lot of time over the past few years having long, angry internet debates about really stupid questions with obvious answers like “should politicians run on unpopular ideas?” or “do moderates perform better at elections?”

Part of why I find that aggravating is that there are lots of more interesting questions out there, like “should you make unrealistic promises to try to win an election?”

On the one hand, winning is good! On the other hand, I feel like Trump set himself up for problems here by overpromising. On the third hand, he’s constitutionally ineligible to run for re-election so maybe he is narrowly correct not to care. But I do think that Democrats should ponder how much overpromising they want to do here. In terms of the upcoming midterms, it probably doesn’t matter. But if inflation is still a dominant concern in 2028, I think they should modulate between taking advantage of public anger while not boxing themselves in too much.

We can have lower inflation

The most important thing about this to remember is that while you can’t realistically promise people a lower overall price level, we could definitely have a lower inflation rate. From the spring of 2022 through to the spring of 2023, inflation was high but it was also falling rapidly. Then for the next year it continued to fall, albeit at a lower rate.

Since then, though, we have genuinely stalled-out at an above-target level.

What’s more, part of how we accomplished that reduction in inflation was higher interest rates. Things like higher mortgage and car payments aren’t technically considered inflation for sound macroeconomic reasons, but in common sense terms, the price of money is a price.

I think it’s quite reasonable to promise inflation at the Fed’s target level. It is Trump who chose, wrongly I think, to spend his whole first year in office bullying the Fed for easier money rather than encouraging them to hit their target first. Of course, the reason he did that is he wanted the lower interest rates. But you can create sustainable lower interest rates with a lower budget deficit. If DOGE had actually identified a large amount of government waste, for example, that would have been a great way to accomplish this.

But they didn’t. And not because there is no wasteful spending, but because they were actually focused on nonsense, political soft targets, and arbitrary power grabs rather than identifying waste. The government routinely spends billions of dollars a year in farm subsidies, for example, and now under Trump we’re making extra bonus payments to compensate farmers for the harm they are incurring due to his trade wars.

I’m not going to say that you could single-handedly end inflation by ending the Trump tariffs, replacing the lost revenue by ending some the Trump tax cuts, eliminating the side payments Trump has made to offset some of the harm of the tariffs, and then cutting unnecessary farm subsidies.

But it would help!

I get that if I were to write “the Democrats’ agenda for 2029 should be technocratic tax reform and scalpel-like cuts in federal spending — plus ideally some big bipartisan fiscal commission to address the larger deficit challenge,” people would rightly say that sounds boring.

But absolutely everyone agrees that voters are fired-up about the cost of living. There’s nothing wrong with politicians trying to put some ideas on the table with some razzle-dazzle. But Trump is not lacking for razzle-dazzle, and after a year in office people are really mad at him. The main thing keeping his standing afloat is that even though he is deeply underwater on affordability, Democrats don’t have that much credibility either.

So Democrats should think hard about what it would look like to reduce inflation and interest rates, and the fact is that what it looks like is mostly boring technocratic stuff and fiscal austerity.

What progressive austerity looks like

To a generation of millennials reared on the political combat of Barack Obama’s first term (or of David Cameron’s ministry in the UK) “austerity” is a dirty word and the whole idea of fiscal discipline feels alien.

But two points on this:

The Keynesian logic goes in both directions: If you believe strongly in fiscal stimulus when there is high unemployment and interest rates are at zero, you should believe in fiscal stringency when there is high inflation and interest rates are not zero.

Obama could have stimulated the economy by backing Republican bills for debt-financed tax cuts. That was considered un-progressive at the time, even though the economy needed stimulus, so he didn’t do it. By the same token, reducing the deficit by raising taxes is a perfectly solid progressive idea.

Which is all just to say that taking deficit reduction seriously doesn’t mean that you need to cut at all costs.

What it means is owning up to the fact that if the public’s top economic policy priority is reducing the cost of living, then when you’re setting your own economic policy priorities, you should put reducing the cost of living pretty high up there.

Any Democratic administration is going to want to make some efforts to raise tax revenue, and they are going to find that raising taxes is hard. There will not be enough revenue to cover everything that everyone wants the government to do. But if the thing that the public most wants is lower inflation and lower interest rates, then the way to deliver on that is to devote the lion’s share of new tax revenue to reducing the deficit.

In one frame of mind, this would be a huge bummer for Democrats who really want to spend a bunch of money on other things.

But I would encourage everyone to step outside themselves for a minute and ask how it looks to you when Donald Trump blows off the public’s desire for attention to the cost of living in order to pursue ideological projects. That’s bad, right? A big part of the point of economic policy is that you’re supposed to be making people’s lives better, making the economy work better for more people. The fact that the mechanism by which a progressive approach to deficit reduction leads to higher living standards is a bit wonky and boring doesn’t change the fact that addressing the public’s complaints about the economy is a really important and worthwhile task.

I would ask people who are passionate about more spending on priority X, Y, or Z that they think is very important to think about identifying less-important or less-effective programs that the government is already spending money on. Progressives have done a lot of good reporting on the many problems with Medicare Advantage, which the left doesn’t like because it’s a quasi-privatization of a beloved public program. So if it’s bad — cut it. That can be a deficit reducer or an offset for some better spending.

This is also where I think “abundance” comes down from the clouds and gets into reality. You actually can push inflation down below two percent without sparking a recession as long as the disinflation is driven by productivity growth rather than weak spending. Any unnecessary or inefficient regulation that you can take off the books helps with this.

Again, I hear the criticism that this is boring and that a political agenda needs to be sexier than this. But it is also literally the public’s number one top priority so how boring can it be exactly? Figuring out how to close the gap between the public’s intense interest in inflation and the cost of living and the slightly humdrum nature of the policies that would achieve this is an interesting problem.

But we’ve just seen Trump spend a full year trying to find a solution that doesn’t involve actually addressing the substance of the issue, and it doesn’t work.

As the beginning of this post notes, I’ll be a bit less active in the comment section this week. I’m traveling around vietnam! If anyone has any recs for Saigon and Hanoi lemme know. I’ll also be around vinh hy

Can I note that the three things Americans probably have the most complaints about are items Dems can actually bring down prices “day 1”. I would say in order they are groceries, cost of mortgages and cost of car loans. Groceries is the item that if you get rid of tariffs cost of a lot goods should actually possibly come down. Furthermore, housing and cars are Americans two biggest purchases. Policies that actually meaningfully bring down the 10-year would actually lower prices.

Back to the tariffs though. It pains me to no end that Democrats seems to be rhetorically supportive of tariffs. That somehow the only issue is Trump is implementing them stupidly. Which at least as the virtue of being true. But my god is there a “horse shoe” theory going on with tariffs. Maybe a reminder that Trump was once a Democrat and this issue might be a reason why. Basically it’s the absurd utterly out of date mental model of “blue collar workers” as somehow all “lunch pail” steel workers. For Trump he wants to bring back these jobs because they somehow bring some fake time when “men were men, grrrr”. But for Dems it seems to be all about bringing back old school unions.

And to piggyback off that last point. I’m not even particularly anti Union. I actually have a decent amount of sympathy for SEIU or workers trying to unionize Starbucks. But these older unions? These relics of an economy that doesn’t exist? I will repeat to Dems; These aren’t your friends! Even the ones who endorsed Harris. The membership of Teamsters, Dockworkers, etc voted for Trump. For the love of god Dems can you please also update your mental model of the modern economy. And to bring it back to the post at hand. You know what can bring down prices? Automating ports! The dockworkers had no greater friend than Biden and it did square root of f**k all. So why are we trying to protect their jobs decades after any time they could deliver votes?