Tax the tourists

Maine should make the Summer People pay

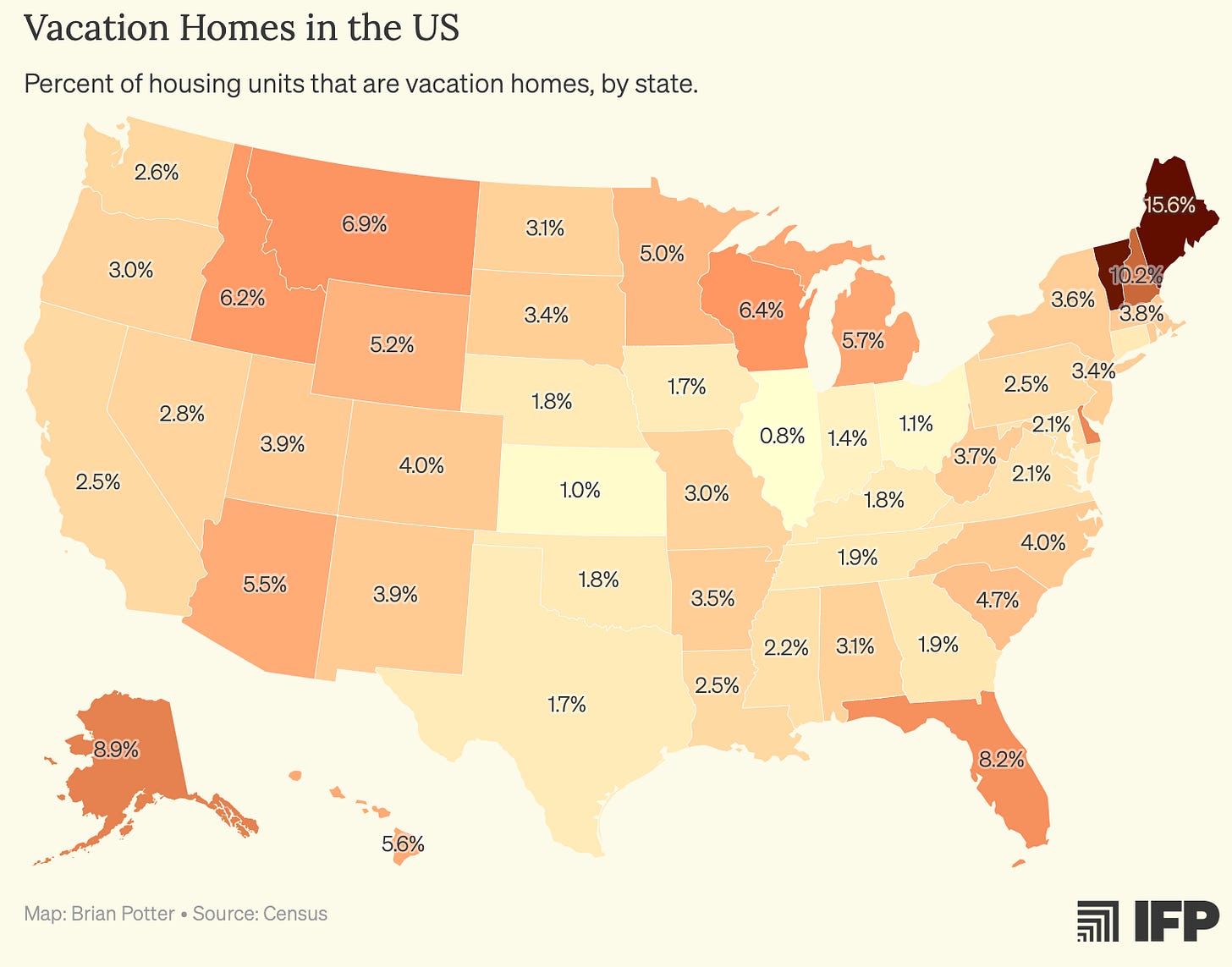

While sitting in my vacation home in Maine, I learned from Brian Potter’s article on vacation homes that Maine is the state where the largest share of homes are seasonal residences — and it’s not particularly close.

This is a fact about the Maine housing stock, but it reveals a larger truth about the Maine economy: While many places in the United States have significant seasonal economic cycles, Maine’s economy experiences the largest systematic seasonal impact. New Hampshire next door is similarly situated, but the impact is smaller. Florida, like Maine, has a lot of tourism. But visits to Florida are less seasonal, and Florida has ten (10!) metro areas with larger permanent populations than Greater Portland, so there’s just a lot more happening there.

People who live in Maine, like most people in places that rely on tourism, have a lot of complaints about tourism.

Bar Harbor, near Acadia National Park, is the epicenter of anti-tourism politics, and they’ve banned new hotel construction and placed strict limits on cruise ship arrivals. It’s easy to understand why affluent residents of a well-located town would take such steps, but tourism is genuinely central to the Maine economy, and I think it’s probably a mistake for the state government to allow the relatively tiny group of people who constitute the year-round population of Mount Desert Island to deprive the entire state of job opportunities and tax revenue.

Indeed, Bar Harbor is a bit of a weird NIMBY vortex. First, the town became unaffordable for the people who work in tourist-serving industries, so they’ve been pushed to Ellsworth and Trenton and Lemoine. Now, the rich people left behind adopt rules that further cut off job opportunities. And despite the economic consequences of this attitude, it’s clearly the dominant view of the state’s year-round residents, who often see the whole tourism complex as antithetical to the state’s heritage industries (fishing, logging, and manufacturing wood products).

But I think there is an opportunity here for the state to reconfigure its seasonal economy as more purely win-win by moving beyond taxing things like hotel rooms and car rentals to varying the sales tax (and related taxes) by season — it should be higher than the current rate in the summer and lower the rest of the year.

The tax status quo

Maine has a progressive income tax and a progressive corporate income tax, plus a 5.5 percent state sales tax and a ban on local governments imposing sales taxes. Prepared foods (and associated beverages) are taxed at 8 percent, rental lodgings at 9 percent, and car rentals at 10 percent.

The problem, though, is that the fiscal condition of towns is incredibly dependent on geography. Local revenue comes exclusively through property taxes, but property taxes are driven by proximity to the coast and to Boston. The outsized share of vacation homes makes this especially relevant. In the town where my family spends summers, about half the structures are seasonally occupied. That’s a windfall for the local school that a town with less coastline simply can’t replicate.

What does provide a statewide benefit from seasonal visitors is the taxes on tourists.

But right now, those taxes are paid by people who make short-term stays at hotels or Airbnbs and who rent cars. If you maintain a vacation house that you drive your own car to, you’re a workhorse contributor to the local tax base, but a minimal contributor to the statewide tax base.

The alignment of incentives is also a little odd. Someone who flies into Bangor, rents a car at the airport, and stays in a hotel while visiting Acadia National Park is contributing a lot to Maine’s tax base. But Maine, like most states, vests most land use power in the hands of local governments. So even though building more hotels in Bar Harbor would drive a lot of state tax revenue, it’s up to Bar Harbor to decide whether that’s allowed — even though it doesn’t drive very much local government revenue. Of course, hotels pay property taxes. But coastal towns are awash in property tax revenue, whether or not they have rental accommodations.

Bar Harbor’s bans mean that Ellsworth, a town halfway between Bangor and Acadia without much scenic coastline, has become the new home for hotel construction.

That’s good for Ellsworth, but it’s a leaky bucket of redistribution. I’ve emphasized before that losses are involved in not allowing housing to be located where the demand is highest, even if there are objectively plenty of homes somewhere. But this is even more true of hotels and vacation rentals. A hotel on the coast drives a lot more revenue (and therefore, ultimately, tax dollars) than a hotel near the coast. But beyond that, if you look at the Maine Office of Tourism’s account of direct tourism expenditures in 2024, “accommodations” alone aren’t bringing in as much revenue as you might think. Restaurants are about the same, and notably, so is the combination of shopping and groceries.

This, again, reflects the fact that a lot of the people in Maine in any given summer aren’t staying in a hotel for a long weekend. They’re staying in houses and buying groceries. And they’re often staying for long stretches of time and coming back year after year and doing things like buying paper towels and blenders and umbrellas and bicycles and towels. The goal of seasonal taxation should be to have all of the state’s consumption taxes be systematically higher when so many out-of-state people are visiting, thus lowering the cost of living for full-time residents.

How seasonal taxes might work

The state of Maine releases monthly reports on taxable sales.

For 2024, their data shows about $3.9 billion in total restaurant sales, which is taxed at the state’s 8 percent rate. Delving into the monthly breakouts shows you could raise the same amount of revenue by increasing the rate to 10 percent in June, July, and August, then cutting the rate to 7 percent in the other nine months of the year. People who are here year-round (or off-season visitors) would pay lower taxes than they currently do, but people who are here only during the high season would pay more.

Crucially, this dynamic applies even outside of food service.

Maine’s “general merchandise” category saw above-average sales volumes in June, July, and August. The seasonality isn’t quite as pronounced here — those sales were also high in December. But that’s just to say that general merchandise sales nationally have a strong seasonal pattern tilted toward Christmas, which in Maine is overlaid with a subsidiary summer seasonality. Building supply and grocery stores see the same pattern of higher-than-average sales in the summer.

And, of course, lodging is incredibly skewed. Half the state’s lodging revenue is booked during three months of the year.

A dedicated wonk with access to more detailed data could come up with a more sophisticated version of seasonally varying taxes. You might want to do it on a week- by-week basis and avoid a steep cliff by phasing the summer rates in and out during shoulder seasons.

The point, though, is that rather than levying heavy charges on direct tourism expenditures like lodging and car rentals, the state should try to make the overall burden of taxation higher during the months when a large share of all kinds of purchases are being made by non-residents. Then the state can lower taxes during the majority of the year, which is good for residents. But it also means that Maine could cut lodging and car rental taxes during the low season and encourage more tourism during the months of the year when the state’s infrastructure isn’t overburdened. Because part of the point here is that while high levels of tourism demand are good, pronounced seasonal demand patterns are awkward and inefficient.

Seasonal demand smoothing is good

There’s a casual restaurant near where my family lives that serves breakfast and lunch most days during the high season.

During the winter months, they’re open for breakfast, lunch, and dinner on the weekends, but they shut down for April and most of May to retool for the busier summer season.

Versions of this are pretty common in coastal towns: The outdoor-only seafood shacks don’t operate during the offseason, and other restaurants maintain longer hours (and often extra outdoor tables because of the nice weather) during the high season. These strong seasonal variations mean that Maine is a great place to be a high school student looking to make some extra cash with a summer job. For most adults, though, it’s not ideal. There’s often little work to be found in the offseason, and many people need to make up for that by working extra-long hours at precisely the time of year when parents of young kids are dealing with schools being out. And from a business standpoint, summer sales are fundamentally limited by labor availability. On a per capita basis, there are a staggering number of job opportunities in Maine right now compared to other states.

To an extent, of course, companies can address this by offering incentives like bonuses and higher pay. But again, the seasonality makes this awkward. Most business owners want to hire the best, most reliable people for the year-round job opportunities. But that means they can’t pay summer hires wages that are way out of line with the base pay, or the permanent staff will (reasonably) get annoyed. And of course, people who have full-time jobs aren’t going to quit them to get a signing bonus for a job that will only last 10 weeks.

This is why, for example, even at the height of the high season, the cafe near my house isn’t open seven days a week and doesn’t try to serve dinner. Everyone adds shifts when demand expands, but there are fundamental limits to how much you can add.

Seasonal taxation would help smooth demand across the year. It must be tempting for year-round residents to splurge a little during summer when it’s easier to make money and when more businesses are open and for longer hours. Variable taxation, though, would encourage year-round residents to save their summer earnings and splurge in the off-season. It would also encourage more off-season visitors. Sustaining a higher level of off-season demand would generate more year-round job opportunities, build a more sustainable labor force for the state, and improve the odds of residents launching and growing successful businesses.

Finally, seasonally varying sales taxes provides particular advantages to the thriftiest families. Most people probably aren’t going to sweat a few percentage points of price difference, but the ones who will are mostly going to be the lowest-income folks. Highly price sensitive people will often be able to time their durable goods purchases for the off-season months when taxes will be lower than under the status quo.

Tourism as a ladder

The ultimate goal here, of course, isn’t just to shift the tax burden onto visitors, it’s to help ensure that spending by non-residents drives a coherent growth strategy for the state.

Maine passed an impressive set of zoning reforms this spring that should facilitate ongoing expansion of the state’s housing stock. This is important in all kinds of places, but it’s particularly important for a state like Maine.

I’m always annoyed by leftists who only acknowledge that supply and demand matters for housing in the context of banning Airbnb and other short-term rentals. At the same time, I have to admit that when people buy vacation houses or start renting out structures as short-term rentals, this does push up the price of housing. The solution is to do what the Maine legislature did and try to make sure that housing supply is elastic, so demand for short-term rentals and getaways turns into construction jobs and retail customers and other sources of economic value, rather than setting off a zero-sum scramble for dwellings.

I think the state should ultimately take a stronger hand on not just housing, but on the hotel and cruise ship issue. The goal, though, has to be to feed this back into things that normal people care about.

This means optimizing the state’s tax structure such that the seasonal influx of visitors constitutes a clear win for year-round residents. Maine has a lot of basic infrastructure challenges — the winter is brutal on the roads, maintaining the electricity grid is expensive, and the state has backed itself into an equilibrium where the working-age population is shrinking. Leveraging tourism into lower offseason taxes could help sustain all that infrastructure while hopefully improving business conditions for non-tourism businesses. That could be legacy industries related to forest products, but it could also be something else. It’s a matter of turning the beauty of the landscape and the large number of visitors into a consistent engine for growth.

In general Cruise Ships bring in relatively little income to the local economy of the ports. This can be characterised in various ways, but one way of putting it is just to say that it's part of the business of a Cruise Line to capture as much of the spending of their customers as possible, and they're pretty good at it.

What you do get is a kind of crowding out of notionally free public spaces, e.g. crowds walk around a quaint village in Maine, pushing out other more economically valuable tourists at the margin.

The solution here is high docking fees or high passenger disembarkation fees, both to pay for additional public facilities, and at the margin to reduce the tax burden on other tourists (or long-term residents).

Unlike most of Matt's tax takes, I don't absolutely hate this one, even if it's not how I would structure my tax code.

But while I can't speak specifically to Maine, I think this misidentifies the NIMBY source in many other resort towns. The permanent residents more or less knowledge that the old year round industries are gone and not coming back in prominence, and accepting the existence of a seasonal economy. And most tourists, as Matt says, are willing to splurge while on vacation.

I think the main NIMBY source are people who own residences in town, but only use them on a seasonal basis. These people tend to have these seasonal houses not only to take advantage of nicer weather, but also to get away from lots of people. Building more housing runs contrary to that desire. And they're the classic types who think that *their* presence is fine because they've owned property there for th proper amount of time (the time they acquired it), but not for *others* who want to enjoy the same place. And Matt's tax proposal doesn't solve what they want, it instead hits them harder.

The bottom line is that people just need to grow up and tolerate the presence of other people, and cities need to stop catering to them and build a stronger economy.