Every few weeks, Twitter kicks around U.S. versus European material living standards, and I’m mostly Team America1 on this.

But this only makes it more striking that Americans have markedly worse health outcomes and life expectancies than residents of Western Europe or rich Asian countries. Indeed, life expectancy in the United States is so bad that the relevant comparison class is a set of much poorer countries like Chile and Poland — countries that are richer than the world average but aren’t even close to the top.

A common left-wing knee-jerk reaction is that this reflects deficiencies of the American healthcare system, but I think that’s mostly wrong.

Despite the shortcomings of the U.S. safety net, the vast majority of people do have health insurance, and America’s track record at disease-curing is actually quite good. But more broadly, “health care” as we understand it is a relatively weak lever for improving life expectancy. Historically the big gains have come from public health interventions like functioning sewer and water systems and fairly simple pharmacological interventions like vaccinations and antibiotics. And for more contemporary diseases, an ounce of prevention in terms of heart disease and cancer really is worth a pound of cure.

But the most sobering aspect of the chart above is that America’s life expectancy is getting worse. Whatever proportion of the U.S.-Canada gap circa 2000 can be attributed to Canadians having universal health care, it doesn’t explain why progress in the United States has halted and life expectancy has started shrinking over the past several years.

And that chart ends in 2019. Since then we’ve had the Covid-19 pandemic. But we’ve also had a large increase in the murder rate. And we’ve also had an increase in car accidents. And we’ve also seen the opioid epidemic worsen.

Since living a long and healthy life seems like a good thing to do, I think Americans should probably spend less time getting furious at each other over small-stakes culture war stuff and more time asking why we’re doing such a poor job of translating our vast wealth and material resources into good health.

Defining the problem

I’m obviously not the first person to notice this.

And one way of thinking about it is as a kind of statistical decomposition problem. When pseudonymous internet personality Xenocrypt looked at this in 2019, his interest was in exploring not the absolute gap between the U.S. and the rich country average, but the growth in the gap. So by his metrics, the high murder rate in the United States isn’t important because the murder gap was shrinking during the relevant period. Conversely, even though overdose deaths don’t account for a large share of the gap, they were a big deal in terms of explaining why the gap was growing.

But this analysis also uncovered some weird facts like, “While deaths by cardiovascular disease at older ages have shrunk dramatically in both the United States and in ‘other rich countries,’ they have shrunk more slowly in the United States.”

That’s good a reminder that the answer to this kind of question is pretty sensitive to the specific question being asked.

Another pseudonymous internet personality, Random Critical Analysis, asked a different statistical decomposition question and finds that the absolute gap is mostly overdoses, homicides, and car accidents:

In terms of the rest, obesity is obviously a big deal. Here, though, one confronts the fact that while obesity is high and rising in the United States, it’s rising everywhere.

My guess is that measuring obesity as a BMI threshold is a bad way to do it. When we say a larger share of Americans than Germans have a BMI of over 30, that represents a whole distribution curve shifted to the right, which means a large increase in the proportion of extreme outliers. You’ve probably seen some version of this chart illustrating why a modest increase in global average temperature can entail a huge increase in the number of extreme global heat events.

If you apply this to body fat and bad health outcomes, you can see why the U.S. — deeper into the danger zone — is pushing more into extreme adverse outcomes.

All that being said, what I am primarily interested in is not statistical exercises but policies. Americans have bigger houses and better appliances and cars than most other people in rich countries, but we have bad population-level health outcomes and we should try to improve them.

The situation is very anomalous

It’s worth underscoring that the situation is weirder than it sounds if simply described as, “Americans die younger than residents of other rich countries.”

That’s because:

On average, life expectancy scales with national prosperity.

America is quite a bit richer than “other rich countries.”

Looking at GDP per capita vs life expectancy, we’re clearly a significant outlier.

But is this all about inequality? Maybe Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos are living high on the hog but the average American has the prosperity of the average Czech?

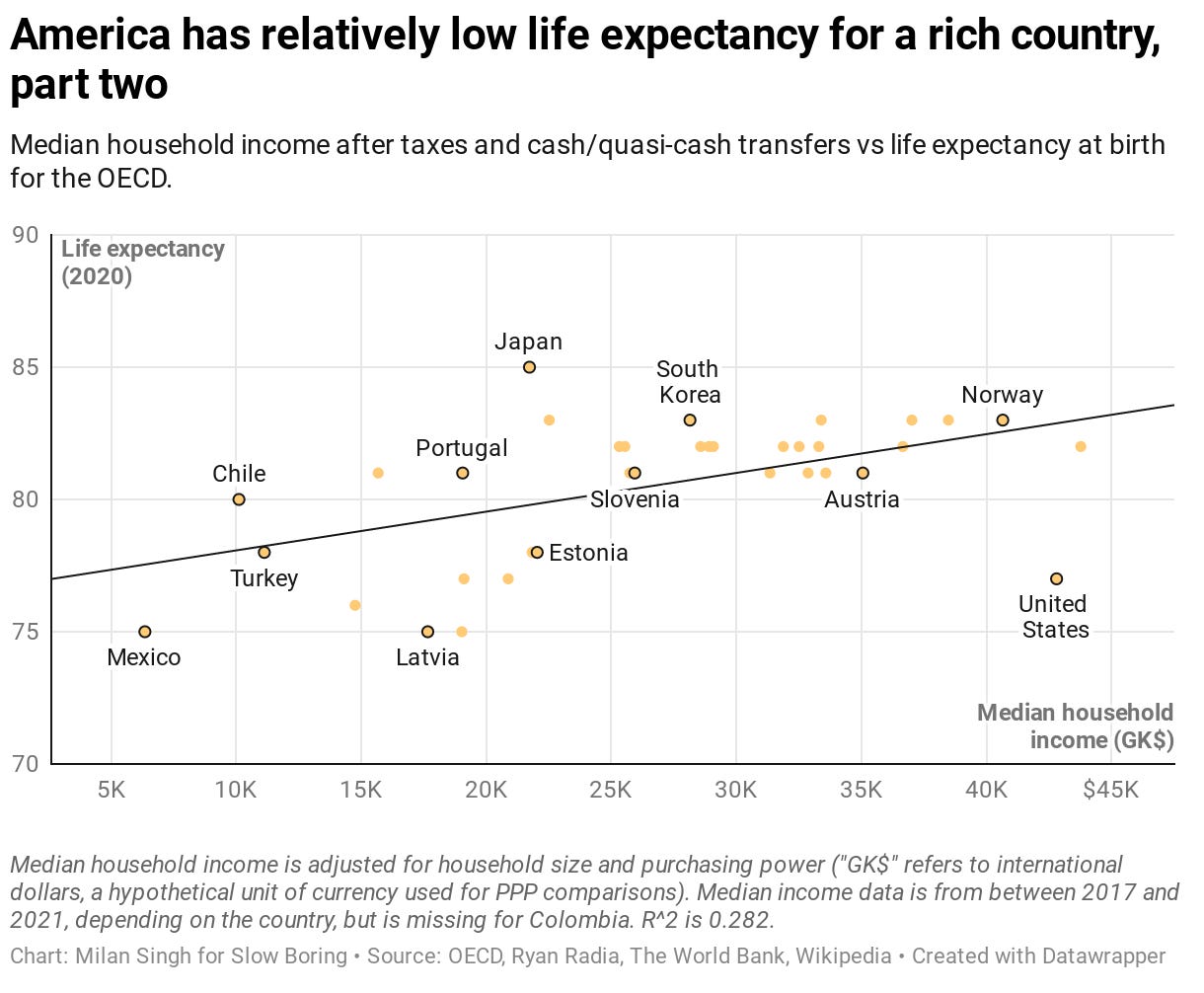

No, looking at this in terms of median disposable income, the U.S. looks worse. The phantom GDP of Ireland and Luxembourg2 goes away, and it’s clear that we are earning like Norwegians but dying like Latvians.

So I think this is the issue — less a statistical decomposition of how we differ from Slovenia than a question of how we can take advantage of the fact that we are much richer than Slovenia to enjoy Slovenian levels of life expectancy.

Now more than ever

There is nothing lamer than a political pundit telling people some new problem illustrates the importance of his longtime hangups.

But to get back on my bullshit, land use policy is implicated in a decent chunk of this. America’s fatalities per kilometer driven are very average, but we drive a lot more than anyone else, including residents of Canada and Australia, countries that are more sparsely populated and that don’t have any cities as dense or transit-rich as New York. Every minimum lot size ordinance, every FAR and height cap, every minimum parking requirement, and every other zoning restriction generates more driving than a neutral market would generate even in a very rich and sparsely populated country. But then all that stuff also contributes to reduced levels of physical activity and poor population-level cardiovascular health.

It’s hard for material abundance to contribute to longevity if our regulatory system forces us to deploy our wealth in unhealthy ways.

Then there is homicide. One way that material abundance manifests in the United States is that we have a staggeringly large number of guns. Some of these guns are legally purchased and then misused in spectacular ways. But many others filter from the legal market into the gray or black market via private sales or thefts. That means that interpersonal violence in the United States is unusually deadly. Gangs fight with guns instead of clubs and muggers stick people up with guns instead of knives. Meanwhile, we have average levels of police funding for an OECD country, despite the much more serious objective risk environment. We do relatively little in terms of surveillance. We don’t have many good active labor market policies to get people out of communities of concentrated poverty.

One could go on about crime at extraordinary length, but one particularly relevant issue here is the tie-in with health care. Medicaid expansion appears to reduce crime largely by expanding opportunities for drug treatment. That of course could also reduce opioid overdose deaths, another big driver of American deaths.

American health care is in some ways very good

Internet progressives often take it for granted that the health care situation of even insured Americans is awful.

I sometimes want to say that the American health care status quo is underrated, but then I remember that surveys always show that the vast majority of insured people are happy with their existing insurance situation. So my actual hot take about this is that the status quo is maybe correctly rated for the majority of people. The tl;dr is that while American health care consumes a lot of financial resources compared to other countries, it also seems to deliver some of the benefits you would expect from spending more money.

A good paper from Samuel Preston and Jessica Ho delves into this:

“The US appears to screen more vigorously for cancer than Europe and people in the US who are diagnosed with cancer have higher 5-year survival probabilities.”

There is a similar, though not quite as strong, pattern with cardiovascular disease — it is treated more aggressively on average in the U.S., and survival odds are better.

A detailed survey of prostate cancer evidence shows that “The combination of earlier detection and aggressive treatment in the US has produced greatly improved survival chances for men diagnosed with prostate cancer.”

Similarly for breast cancer, America does more early screening and more aggressive treatment with the result that “the US has experienced a significantly faster decline in breast cancer mortality than comparison countries.”

None of this is to say that all is well with American health care.

In particular, health insurance is first and foremost an insurance product. Foreign healthcare systems do a very good job of redistributing economic resources from the healthy to the sick, shielding people from catastrophic financial misfortune induced by illness. The risk in America is less that you’ll die and more that you’ll be bankrupted. This just turns out to be less relevant to life expectancy than you might think.

The broader question, that I think is harder to answer, is about the impact the American healthcare system has on non-acute health care. The studies I’ve covered so far show that people with acute health needs get good treatment in the United States. But we also have studies showing that Medicaid expansion (which is tragically incomplete) has important benefits in terms of making addiction treatment services more broadly available. A big open question in the research, it seems to me, is how much good it would do across the whole spectrum of lifestyle choices if every American could routinely access non-acute routine healthcare services for free.

Could doctors be getting lots more people into basic treatment for addiction and mental health problems? Could we have earlier and more effective interventions for obesity? It’s all well and good to say, “it’s not that we’re bad at treating cancer and heart disease, it’s that our population is so ravaged by cancer and heart disease.” But that still leaves you with the question of why we are so ravaged, and I think the organization of the healthcare system is plausibly a factor.

Health and inequality

It probably doesn’t come as a huge surprise to learn that low-income Americans have worse health outcomes than richer ones. Or that this gradient is steeper in the United States than in Europe.

But the actual truth about health inequality turns out to be a little bit weirder than you might think. A huge team of researchers took a look at this last year by binning people according to where they live, then organizing geography by “poverty rank” to compare Americans who live in the richest 20 percent of areas to Europeans who live in the richest 20 percent of areas. They found that poor Americans die at dramatically higher rates than poor Europeans. This is especially true if you’re talking about poor Black Americans, but it’s true of white ones as well. But the striking thing is that rich Americans also die at higher rates than rich Europeans. In fact, as of 2018 (i.e., before the death rate in America started surging), rich Americans died at roughly the rate of poor Europeans.3

So there is both an important inequality story here, and also a story that isn’t about inequality at all. Rich Americans are much richer than rich Europeans (to say nothing of poor Europeans!) and are still in relatively poor health. And while I think we urgently ought to fully expand Medicaid and enact big cuts in child poverty, clearly neither of those things will address the underlying health gap. Addressing murders, car wrecks, and drug overdoses is critical. But I think it’s worth looking pretty hard at more forceful interventions into behavior.

Taxation for public health

I’ve written before about the case for higher taxes on alcohol and don’t want to fully rehash that except to say that booze taxes are very good.

There are more deaths attributable to alcohol each year in the United States than there are deaths attributable to guns.

There is some overlap between these categories because alcohol is involved in a lot of crime.

While most alcohol deaths are the drinker killing themselves, drunk driving is a non-trivial source of mortality for bystanders.

The conventional wisdom in the United States that alcohol prohibition was a mistake is correct. But the conventional wisdom does miss two key points: alcohol consumption really did fall, and despite the increase in organized crime activity, there was an overall reduction in crime and violence because drunkenness is a big problem.

We could capture a large amount of the upside of prohibition with few of the downsides by raising taxes and returning to the 20th-century practice of “voluntary” restrictions on alcohol advertising.4

And even though it seems politically implausible at the moment, I’d go much further than this on the tax front. The United States is the world leader in sugar consumption by a large margin, to our detriment. My read of the science is it would be good to tax all sweeteners pretty heavily. Not that this would eliminate desserts from the world, but it would strongly discourage liquid calories and the use of stealth sweeteners in processed savory dishes. And like all the earnest wonks have been saying forever, we should eliminate subsidies for staple crops like wheat, corn, and soy.

I know broad-based tax hikes seem inconceivable in today’s politics. But Social Security is scheduled for large automatic benefit cuts in 2035, and that’s not very politically palatable either. Between inflation, the steady upward march of public sector health spending, and the looming Social Security shortfall, I think there may be a new era of austerity politics coming around the corner pretty soon. And as long as Congress needs to choose between a range of politically dicey options, I think they really should take a hard look at things like higher gasoline taxes, carbon taxes, and taxes on booze and sweeteners. There is nothing wrong with taxing the rich, too — America has plenty of fiscal needs, and part of my public health agenda is to redistribute via Child Tax Credit and Medicaid expansion — but I think it’s clear that the pattern of consumption in the United States is contributing in important ways to our bad health outcomes, and we ought to do something about it.

Long story short, Team Europe inevitably ends up comparing the U.S. average to idiosyncratically rich parts of Northern Europe. But if you limit your attention to idiosyncratically rich parts of the northern United States, it’s clear that Massachusetts is similar in scale to Finland or Denmark and much richer.

For tax purposes, multinational companies are incentivized to get creative about finding ways to attribute as much profit as possible to their subsidiaries in Ireland and Luxembourg.

The other interesting thing here is the very large gains in Black life expectancy over the past generation. A lot of this is the decline in crime and improved treatment for HIV/AIDS, but that doesn’t fully explain it — some other stuff is getting better.

The current legal doctrine where a state can make alcohol illegal but can’t ban booze on ads television is not very logical, but it means that legislators and regulators can bully trade associations into curbs on advertising in exchange for not being driven out of business entirely.

It’s cliche/overly simple, but certainly America’s culture of individualism/liberty/“muh freedoms” or whatever you want to call it comes into play. Americans of both parties place high value on allowing other people to do what they want, or at least they themselves being free from the moralizing and micromanaging of people who think they know better. And the clear outcome at a societal level is, people die. Now I sound weird and authoritarian. But it’s pretty simple- most moral pressure in groups is rooted in the idea that if everyone did X, we’d see better group outcomes, even if individuals might feel a little stifled. It’s easy to see that on things you agree with- “if no one had guns, we’d have fewer deaths!” vs things that code as “the other guys”- “if no one had sex til they were married, we’d have fewer out-of-wedlock kids and they’d grow up in more stable homes!” (See also Nellie Bowles’ piece on liberals who fight for the right of people to choose to die on the streets of SF.) Anyway I could go on and on here. But your thesis is refreshingly straightforward- what can we do from a *policy* perspective? And I just caution that any policy that aims at expanding life expectancy runs the risk of being coded by the voters as “nanny state thinks they know better than me how to run my life!” which is political poison in our culture. That said I think it’s possible to thread the needle, and your ideas aren’t bad. But gas and sugar taxes won’t be popular. (Also I thought this piece was very interesting and well-done and I learned quite a bit!!)

I really thought footnote 1 was just going to say "Fuck Yeah".