The case for higher alcohol taxes

It turns out that alcohol is pretty bad

This is not particularly in the news, but I think one of the most underrated basic public policy points around is that the consumption of alcoholic beverages is a pretty serious public health problem.

Now don’t get me wrong, I enjoy a drink now and then, and I enjoyed more drinks more frequently when I was younger. A lot of people derive immense satisfaction out of alcohol as a complement to socializing or find winding down with a glass of wine at the end of the day to be incredibly relaxing.

But I don’t think we really have any kind of clear consensus on how to weigh everyday pleasures against public health concerns. About 40,000 people die each year from injuries inflicted by firearms, of which more than half are suicides. In some social circles in the United States, that’s seen as an acute crisis worthy of drastic political action to curtail the tide of violence. CDC stats say about 95,000 excess deaths each year can be attributed to alcohol abuse, of which about 10,000 are drunk driving fatalities. So looked at one way, booze is deadlier than guns. Looked at another way, gun murder is a more serious problem than drunk driving. Either way, to the extent that you’re inclined to see the gun situation as worth major legislative action, I think it’s certainly worth looking at alcohol as well. Indeed, scholars think that something like 40% of murders involves the use of alcohol, so the issues really are fairly comparable.

Obviously, we’re not going to create mandatory background checks for buying liquor or ban high-capacity kegs of beer. But there are some attractive policy options in this space — like taxes — that could generate revenue while saving lives.

Alcohol has gotten much more affordable

We tax alcohol in the United States, of course, but we’ve chosen to do it in a slightly odd way that treats beer, wine, and liquor differently.

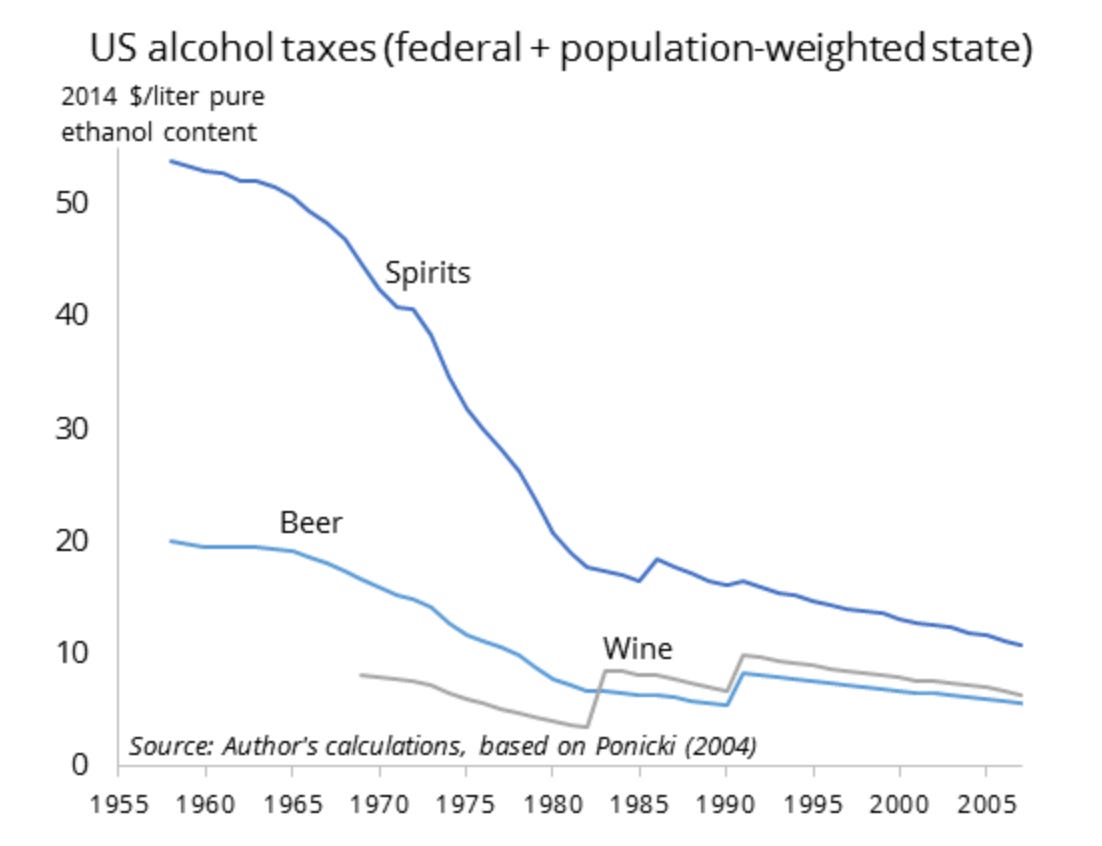

As a side note, the favorable tax treatment of beer relative to liquor helps explain the rise of “hard seltzer.” You could combine vodka and carbonated water in a can, but that would be taxed as liquor. Eventually, people figured out a process for creating a flavorless malt liquor — “hard seltzer” — that is taxed like beer. But as you can see here courtesy of David Roodman, the big picture is that inflation has eroded the value of all of these taxes.

This is particularly significant because household income has also risen a lot since 1960. So the real value of the tax on beer and spirits has not only fallen considerably, but the affordability of paying the booze tax has surged over the generations.

And of course, there is also the underlying product. Certain things have seen their prices rise much faster than the rate of overall inflation — that’s normally labor-intensive services like child care and education. Other things, mostly related to computers, have gotten much cheaper. Alcoholic beverages are about average — the nominal price is higher than it was 30 or 40 years ago but in line with overall inflation. So as incomes have risen, alcohol has gotten more affordable.

Drinking causes problems — not just for the drinker

When German Lopez made the case for a higher alcohol tax at Vox a few years ago, he noted that “if you care about gun violence, or car crashes, or the current drug overdose crisis, or HIV/AIDS, you should care about alcohol — because alcohol’s annual death toll is higher than deaths due to guns, cars, drug overdoses, or HIV/AIDS ever have been in a single year in America.”

With crime on the rise, I think it’s particularly important to note the role of alcohol in perpetuating violence.

“Take any dimension of the problem you like, except for source country violence,” the late crime scholar Mark Kleiman told the Washington Post in 2013. “All illegal drugs combined are to alcohol as the Mediterranean is to the Pacific.”

He explained that surveys of incarcerated people reveal that half the people in prison were drunk at the time they committed their offense. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they wouldn’t have committed the crime if they’d been sober. But we all know that drunkenness reduces inhibitions and time-horizons (that’s why it’s fun, right?), and uninhibited people who don’t think about long-term consequences commit more crimes.

That interview ran eight years ago, and at the time, I think Kleiman’s point about this mostly played as a kind of somewhat theoretical argument about drug policy. It was perverse to be so harsh on marijuana and so lax on alcohol. The rational course was to legalize recreational cannabis in some form (including high taxes) and to also put higher taxes on alcohol. Today though, with crime creeping back onto the public agenda, I think it’s more of a first-order thing. If you want cities to reduce crime without resorting to more policing, higher alcohol taxes do that. And if you want cities to reduce crime by hiring more police, well, higher alcohol taxes generate revenue.

Back when higher alcohol taxes were in the mix as a potential revenue source for the Affordable Care Act, Kleiman estimated that doubling the tax on beer would generate a five to 20% drop in assaults.

Of course there’s more to alcohol than crime. But I dwell on the crime a bit because it’s politically salient, as it underscores that alcohol isn’t just a paternalistic public health issue (the way smoking is), and also because it suggests the CDC death toll may be an understatement. If a drunk person gets in a fight and the fight turns deadly, or if a drunk person does a carjacking that turns fatal, those are assault deaths, not alcohol deaths. But we would have fewer of them with less drinking. Alcohol is also strongly related to rape and sexual assault.

Alcohol taxes hit richer people harder

American politics is very averse to any kind of tax increase that doesn’t strictly target the richest people. And you will hear it said that alcohol taxes are regressive.

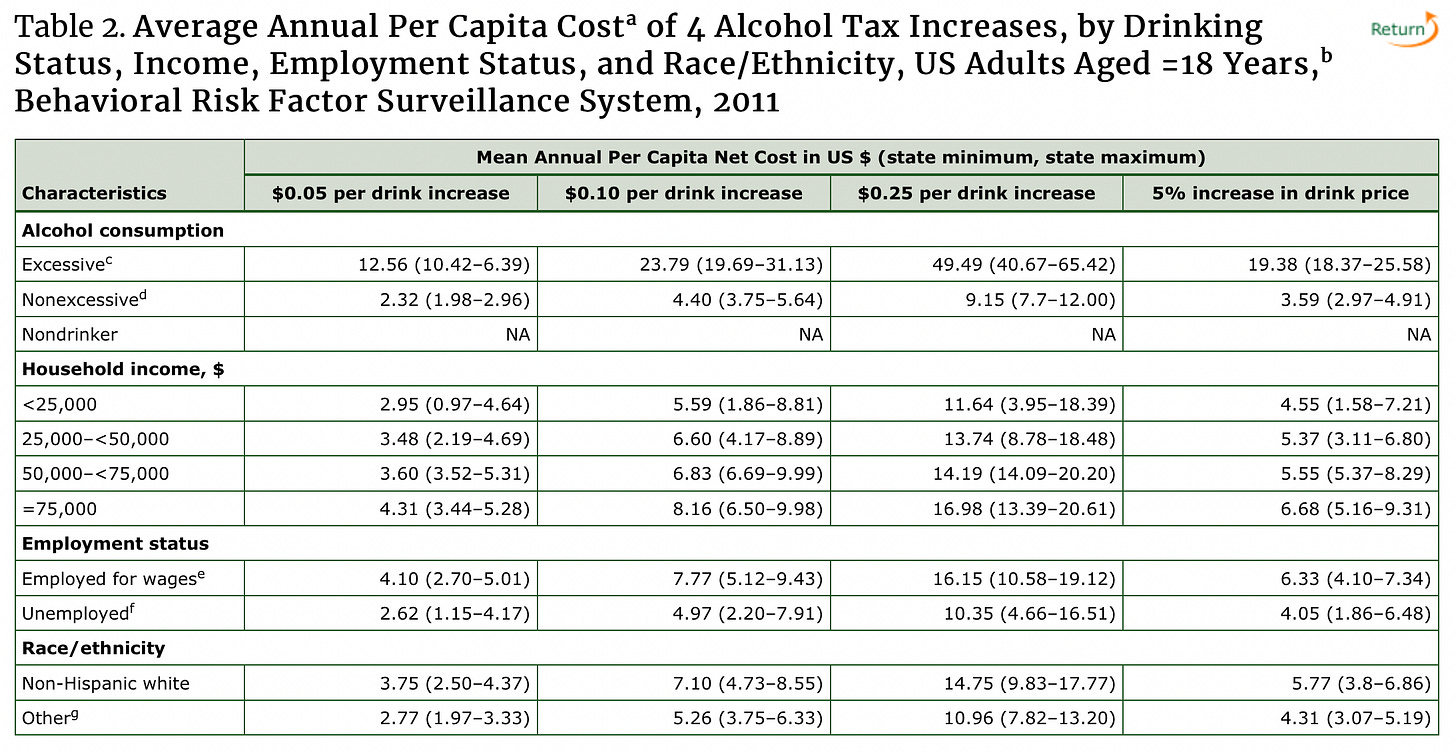

But alcohol consumption rises with income, and as these CDC simulations show, higher taxes on alcohol would hit more affluent people harder.

For the sake of honesty, it is worth saying that as far as I know, basically any tax on consumption of anything that normal people buy ends up being regressive with respect to really rich people. That’s because, on the one hand, rich people save a lot of money — recalling that something like buying a $3 million beach house counts as “saving” in the national accounts. Rich people also buy a certain amount of special rich people products like yachts and luxury watches that no normal person would ever buy. So beer expenditures end up being a smaller share of income for someone earning seven figures than for a normal working-class person.

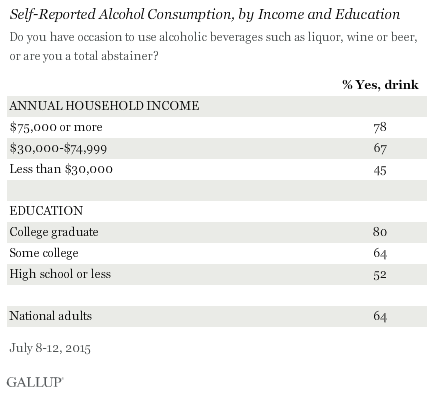

This Gallup survey is also telling, revealing that abstention from alcohol is a low-income working-class phenomenon in the United States.

So unless you’re going to eschew literally any kind of broad-based tax whatsoever, I think alcohol taxes fit a plausible concept of progressivity.

I would add to the CDC analysis, though, that the American practice of taxing per unit of volume isn’t the only way to do this. For reasons that are pretty obvious, the public health people mostly worry about the minimum price of the cheapest drink. But you could combine a price floor with an ad valorem tax of X% on the retail price of the drink.

That would raise more revenue and make the tax more progressive. I also tend to think that, in basic political terms, normal people think that people who drink very expensive bottles of wine are ridiculous. But I will admit I don’t have polling to back me up on this — it’s just a guess.

Higher taxes mean less drinking

A lot of people seem to be skeptical that higher alcohol taxes would have a meaningful impact on any alcohol-related problems.

Conveniently, not only is there a lot of research out there about this, but David Roodman reviewed it for the Open Philanthropy Project and, in many cases, did replications of the underlying studies. And the evidence is pretty clear that higher taxes mean less drinking. There is even a convenient pattern that explains why this isn’t a universal finding. Roodman says that the “overall pattern across the quasi-experiment studies is that the larger the experiment—the larger the price change—the clearer the effects. The 7% tax hike in Alaska on October 1, 2002, and the 18% cut in Finland on March 1, 2004, are leading examples.”

So while you can find studies that find a null effect, it seems pretty clear across the whole set of studies that alcohol consumption is responsive to prices, and overall it seems like every 1% increase in the price of alcohol leads to a 0.5% reduction in consumption.

If all of that fall in consumption came from pushing light drinkers into total abstention, the public health gains would be small. The idea that moderate drinking is good for you appears to be a myth, but we don’t see very strong evidence for major harms from moderate drinking either.

Roodman’s view is that looking only at alcohol-related disease, “a 10 percent price increase would cut the death rate 9-25 percent,” saving several thousand lives per year.

Thinking broader on taxes

In terms of what’s immediately on the congressional agenda, I think Emily Stewart and the Biden administration have it right — just tax the rich.

Indeed, I would further note that Biden “pays for” new spending in part with a timing mismatch with his Jobs Plan. You have 15 years of revenue offsetting eight years of spending. That’s appropriate, I think, given today’s low interest rates. In effect, you are financing the infrastructure with borrowing and then paying it back over time.

But even though Biden’s proposals are big, they’re not big enough to be a “forever agenda” for American politics. As a candidate, Biden promised significant investments in Section 8 housing vouchers and Title I funding for K-12 schools. His expanded Child Tax Credit cuts out the richest 2% of families to save a little money, but that contributes to administrative burdens that reduce participation among the genuinely eligible in a way that saves another good chunk of change. But those are bad savings; we should make the program genuinely universal.

The post-ACA health care system really is a lot better than the prior system in a way that people often underrate. Slow Boring, for example, probably wouldn’t exist without the ACA exchanges. But it’s still really, really, really not a perfect system, and we need to do more here. I like the Data for Progress public infrastructure for care idea a lot.

But the reason Biden hasn’t even proposed the full Biden Agenda is there really are limits to how much revenue you can plausibly squeeze out of just the very rich. You need to persuade people to endorse some broad-based taxes as well. And while I’m not going to try to tell you that a higher tax on booze can pay for a full social democratic welfare state (it absolutely cannot), what is true is that in the realm of broad-based taxes, taxing booze is one of the best kinds of taxes — delivering significant gains to public health and public safety even before you spend the money.

I own a craft distillery and this is the by far worst Yglesias take I've ever seen. I'm just being objective.

Don’t have a lot of brainy stuff to add but I like that Matt references Kleinen and wish he would have done a deeper take on Kleinens criticism of our lack of alcohol regulations. I was persuaded by his illustrations of how much the alcohol industry is dependent on alcoholism, how your average neighborhood bar needs the neighborhood drunks and caters to them, how most of the advertising revenue in booze centers on the cheapest lowest quality stuff partly because that’s what alcoholics prefer, how there is a huge incentive to get people to drink as young as possible and this pervades advertising patterns and ought to be redirected away from young people through regulation. Simply his stat of x percent of alcohol is consumed by y percent of people, x being surprisingly big and y being surprisingly small was eye opening. I drink, but alcohol is bad and we shouldn’t be so skiddish about regulating it and taxing it to minimize its harms.