Schools are getting worse in most red states

The “Southern surge” is great, but it’s just four states.

I am a believer in the “Mississippi Miracle,” where one of America’s worst-resourced school systems has achieved some of its best results in early reading through solid training and rigorous implementation of best practices. More broadly, I am bought in on the idea of what David Brooks hailed as “the biggest education story of the last few years … the so-called Southern surge, the significant rise in test scores in states such as Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Tennessee.”

But I do think it’s important to pay attention to the limits of this story.

It’s not a significant rise in test scores in states such as Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Tennessee. It’s just those four states.

That’s a great achievement by those states, but I’ve seen a fair amount of discourse using their example to hail red state governance more broadly.

Viewing this through a narrow partisan lens, it’s worth noting that Louisiana’s turnaround mostly happened under John Bel Edwards, a Democratic governor. But more to the point, there are way more than four red states. If we were actually seeing broad-based educational improvement as a result of conservative governance, that would be much more embarrassing for Democrats but much better for the country than the reality.

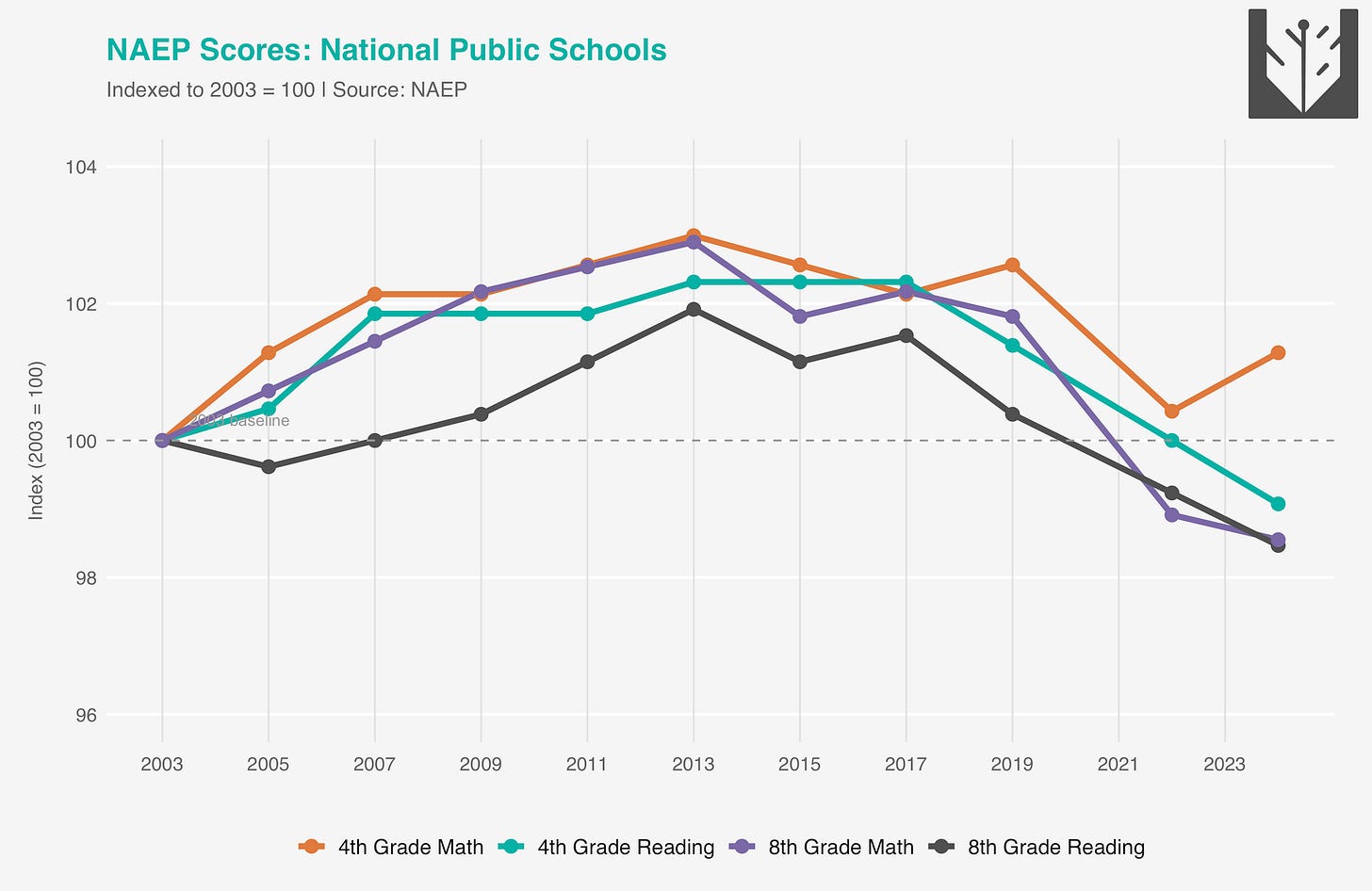

One reason that Mississippi has shot up the rankings is that not only have its scores been going up, but scores in most places are getting worse. As a result, a state can now be a top performer with results that would have been pretty average a decade ago.

That’s not to take anything away from Mississippi, where schools and state officials are doing a truly excellent job of combating these serious national headwinds.

But if you want to understand what Mississippi’s results do — and don’t — mean for American society, you need to get the ratio of figure to ground correctly. Mississippi stands out partly because the national background has gotten worse. Most red states aren’t seeing similar improvements, and students in blue states aren’t doing well either. The failures look different, but they’re still bad.

Probably the best thing you can say about the conservative approach to education right now, all things considered, is that when Republicans give you a school system that doesn’t work, they also won’t spend too much of your money on it, which is at least coherent.

It would be nice, though, if both parties would take the task of school performance more seriously. This means not just learning from Mississippi, but re-embracing some of the lost lessons of the No Child Left Behind era.

The “Southern sag” that I just made up

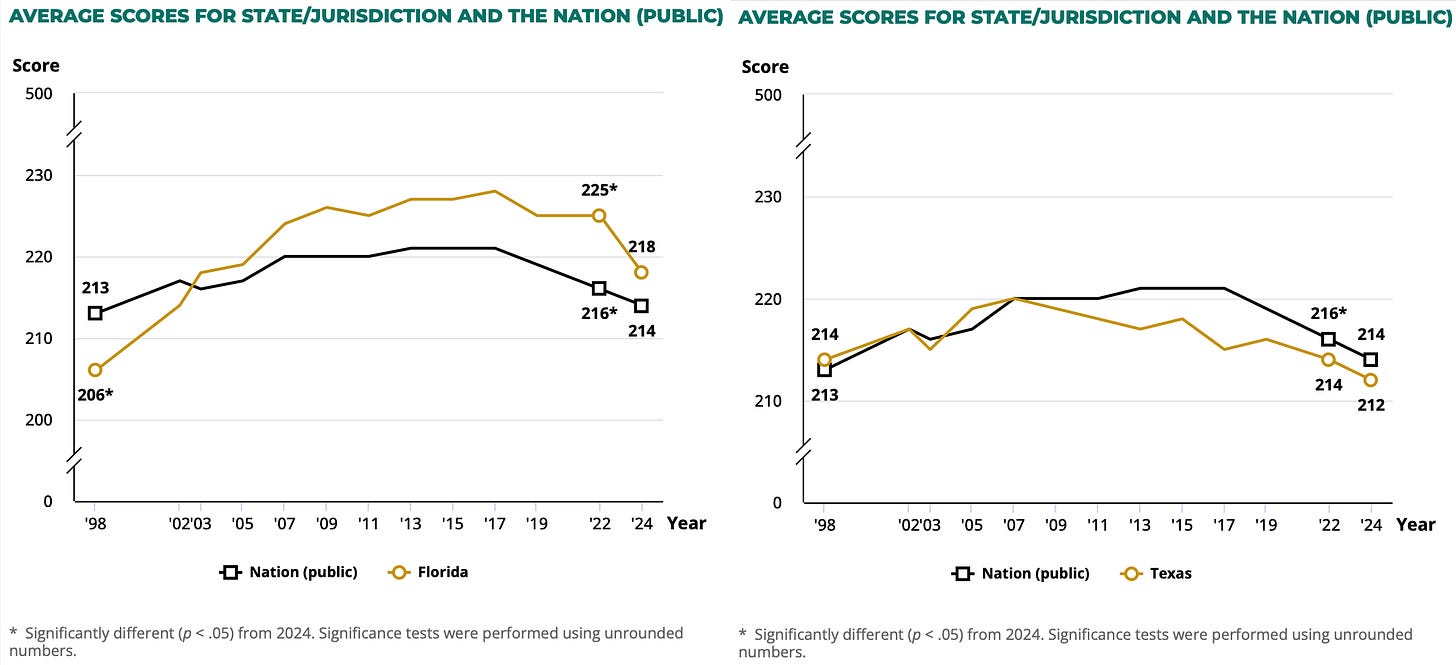

Consider that if you add up public-school enrollment in all four surging states, it’s about equal to the number of school kids in Florida, while Texas has many more students than that. When I was a young pundit, Texas and Florida were the examples smart journalists would cite of conservative states that were counterintuitively doing better than virtue-signaling liberal states at educating their students. If the surging four were now joining Texas and Florida in delivering good results, that would be incredible news for America’s kids.

But look at the fourth-grade NAEP reading scores in Texas and Florida — they’re getting worse!

This “Southern sag,” unfortunately, involves more than twice as many children as are benefiting from the Southern surge.

Of course it doesn’t make a ton of sense to talk about a Southern sag, since there’s nothing distinctively Southern about it. It’s just that national scores have gone broadly down. They’re down in the South and down in the Midwest and down in every other region. They’re down in blue states and they’re down in red states. The achievements in MS/AL/TN/LA are genuinely worth celebrating and paying attention to, but the fact that Texas and Florida and all kinds of other places are moving backward also underscores that you can’t just blame Democrats or teachers unions or believe that Republicans have this figured out.

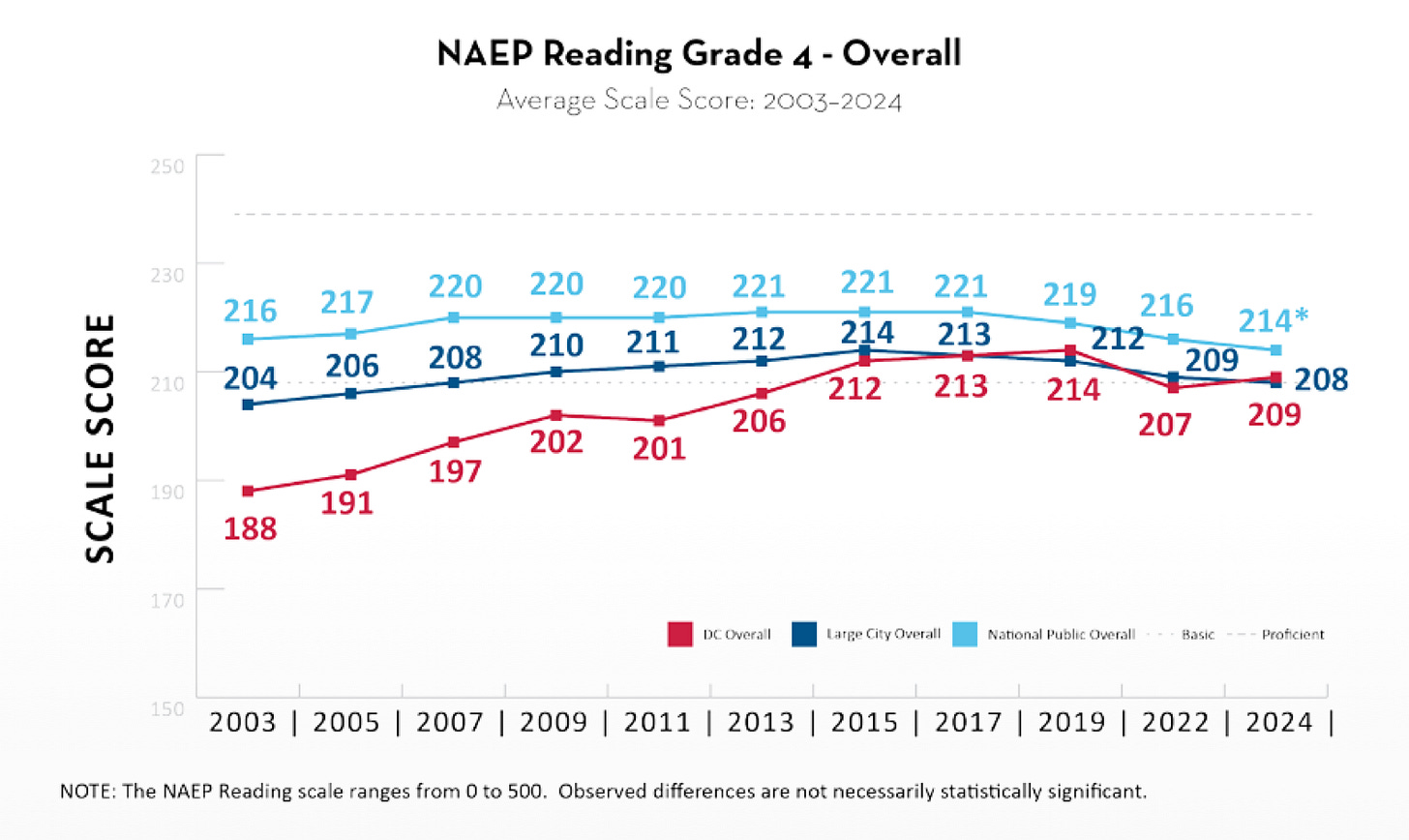

Indeed, the other “state” that has done pretty well during this period is Washington, D.C., which was a wildly below-average school system when I first moved here and is now almost exactly average for a big city.

D.C.’s fourth-grade reading achievements are not as impressive as Mississippi’s, but on the flip side our eighth-grade reading scores have improved more than theirs, indicating that we have perhaps done something right.

And I would say that one of the big things that is driving success in the minority of places that are succeeding is that those places are trying.

Accountability is key

The No Child Left Behind law that was passed on a bipartisan basis in 2002 seems to have worked well. But it led to significant bipartisan backlash and was largely dismantled in Obama’s second term, and things have generally gotten much worse since then.

And yet, almost nobody is calling for going back to a system that was delivering improved results.

I think people know, broadly speaking, that teachers and unions generally did not like No Child Left Behind because it threatened negative consequences for a poor-performing minority of schools. This reflects poorly on them and conservatives are right to believe that public sector unions often lead to bad public sector outcomes.

But in most cases, rather than “it reflects poorly on unions that they oppose effective education reforms, so we should blow them off and run school systems,” the trend on the right has been to behave as if the goal of education policy is to dismantle teacher unions. As a result, the biggest reform trends have not been the kind of curriculum efforts we see in the Southern surge states.

Instead, there’s been a ton of enthusiasm for vouchers and education savings accounts, which are basically efforts to replace public-school funding with tax breaks for spending money on your kids’ education. The evidence on the effectiveness of these programs has generally been negative in terms of the impact on student achievement. This is true including (and perhaps especially) in states like Tennessee and Louisiana, where the mainstream public-school systems have been getting good results.

The basic issue here, as we know from the higher education market, is that schools don’t really compete on the basis of being highly effective at teaching students.

The “best” colleges in America are the ones that attract the strongest applicants. And most students just want to go to the “best” schools. Nobody even attempts to measure whether the teaching and learning practices at Harvard and Princeton are effective; it’s not considered relevant to the undertaking. If you have strong religious motives for wanting your kids to attend private school, if you’re rich and inclined to send your kids to private school anyway, or if you’re not particularly interested in education and just favor the downstream political-economy impact of harming teachers unions, then subsidies or tax breaks for parents of private-school students is a great approach.

But if the problem with unions is they oppose accountability for results, then the solution can’t be to shift to a privatization system that makes accountability impossible.

Progressives should get their act together

What I will say on behalf of the conservative approach to education is that, while it doesn’t work, it’s at least coherent. Vouchers and education savings accounts do not, in practice, lead parents to select highly effective schools for their kids. But if you do want to do that, you’re allowed to under a privatized system.

And more broadly, while the school performance trends in Texas and Florida are bad, the school systems are at least cheap to run. I would say the general deal with state government in Texas is that Republicans have made it a very harsh place to be poor. There’s no Medicaid expansion, stingy benefits, a criminal justice system that’s focused on insulating the affluent from crime rather than having low rates of violence, and generally bad public health outcomes. The school system evolving in the same direction of doing a bad job serving high-need cases would be of a piece with all that.

But in defense of Texas, Republicans don’t really run around claiming to be the people who care a lot about helping poor people.

Democrats have landed in a weird equilibrium where they typically do say that things like public schools and education and the well-being of poor kids are important.

If nothing else, they generally want to spend a lot of money on public schools — in which case they really ought to care a lot about whether they’re doing a good job.

A long time ago, a union leader offered “We can’t have public money without public accountability” as an anti-voucher line, and I think it was a good one. But then you have to have accountability in your public system!

One of the striking things about the No Child Left Behind era is that a lot of the abstract, high-level criticisms of the law made perfect sense. It’s not really reasonable to expect public schools to eliminate “achievement gaps” or deliver universal proficiency. In a country with millions of kids, if you have any kind of reasonably rigorous standards, then someone is going to end up left behind.

But despite these conceptual flaws, the simple step of measuring results and imposing (generally very mild) consequences for bad performance was good. It’s true that this annoyed various stakeholders — not only teachers, because parents did not like hearing bad news about their school or their kids. But as adults, I think we understand that you can’t actually improve at something unless you’re willing to get some negative feedback.

The Virginia test case

An interesting test case is coming down the line in Virginia.

The state has a newly elected Democratic governor, Abigail Spanberger, who has been cultivating a moderate brand. A new Democratic trifecta is obviously not going to voucherize the Virginia public-school system or cut school spending to give everyone a tax break. What they ought to do is what you would expect Democrats to do with a public-school system: try to make it better so as to deliver better results, especially for high-need kids.

The federal government is no longer trying to make states hold schools accountable for performance, but state governments are still allowed to do this. And as it happens, Glenn Youngkin’s outgoing administration brought in two former Obama Education Department hands (including friend of the newsletter Chad Aldeman) to recommend changes to the state’s school accountability system, recommendations that were released in December while Youngkin was a lame duck.

Going forward with these recommendations would help new Governor Abigail Spanberger deliver some real results on education quality and build her résumé for national leadership. On the other hand, she already spurned the state’s unions during the campaign by saying she would keep Virginia’s right-to-work status, and there’s some sentiment that she therefore owes labor some favors.

This doesn’t really make a lot of sense to me.

Having already done the courageous thing, stiff-arming the groups and winning without them, she should try to deliver on the idea that Democrats care about the quality of public services. There’s no real reason that “schools should do a good job of teaching” should be a right-coded idea — it’s not reflective of the trends in most states where Republicans are governing, and indifference to school quality does not align with any progressive ideas or values.

Aaccountability is all well and good, but at the end of the day school systems live or die based on middle class buy-in.

Big urban systems need to work to make neighborhood schools into places where middle and professional class families want to send their kids even though they’re not as new as private alternatives and even though the children of their poorer neighbors will be there too.

As a starting point that means getting public safety and discipline/classroom disruption under control, and it means tracking. None of these are popular with teachers’ unions and they’ll need to be run over with a truck to implement them, but there’s no particular need to do any more than keep them out of decision making about policy and pedagogy. They’ve not negotiated an insane sweetheart deal for themselves, they’re not longshoremen.

The tragedy of progressives’ fetish for gap reduction is that it turns measurement into a vice. It’s easier to narrow gaps by slowing high performers than by lifting low ones. If reducing gaps is your primary focus, measuring things will, at a minimum, push towards neglecting top achievers.