American students are getting dumber

It started before Covid, and it keeps getting worse.

One of the major themes of my writing is that mass media is driven by negativity bias, which is driven by audience behavior, and this is slowly driving us all crazy.

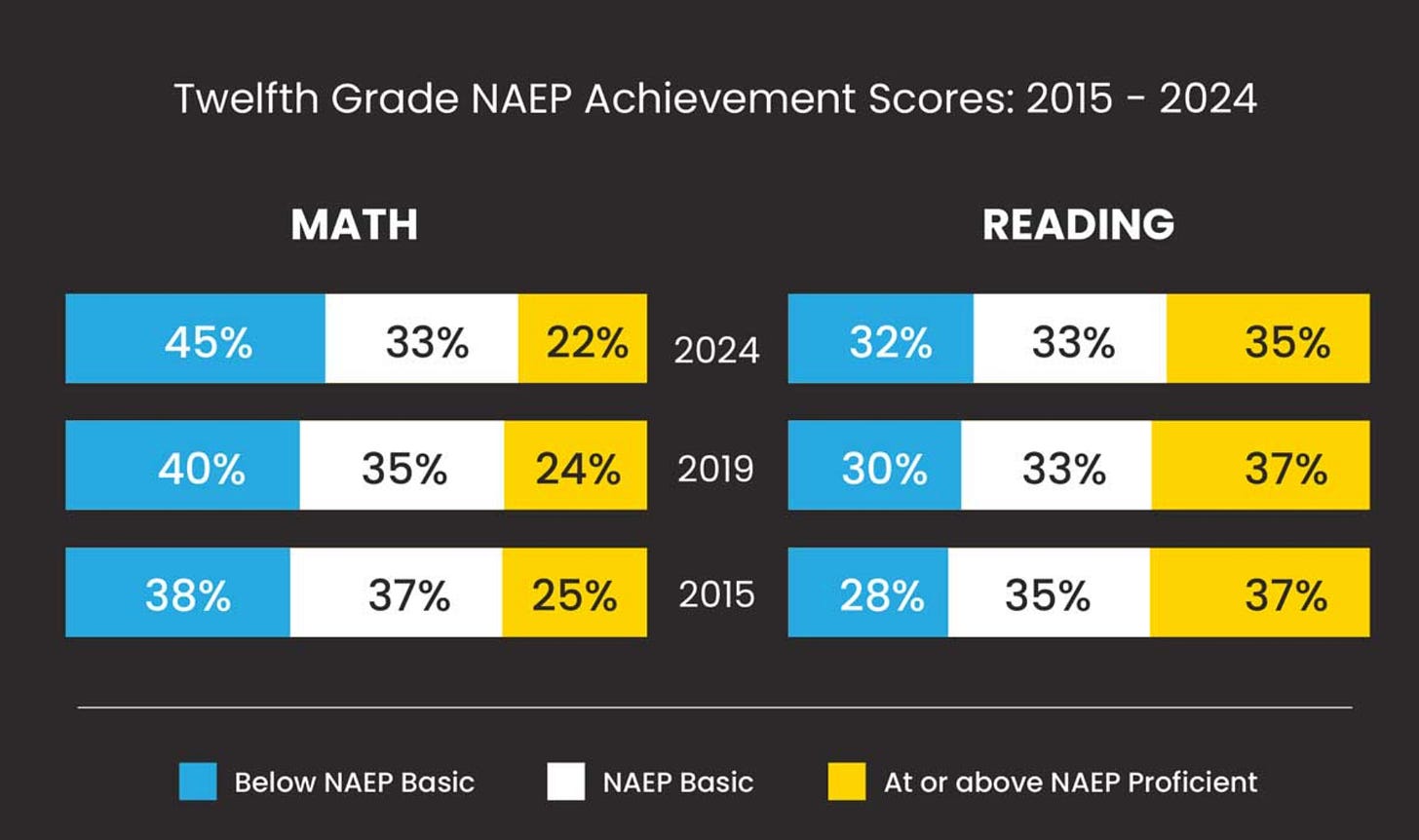

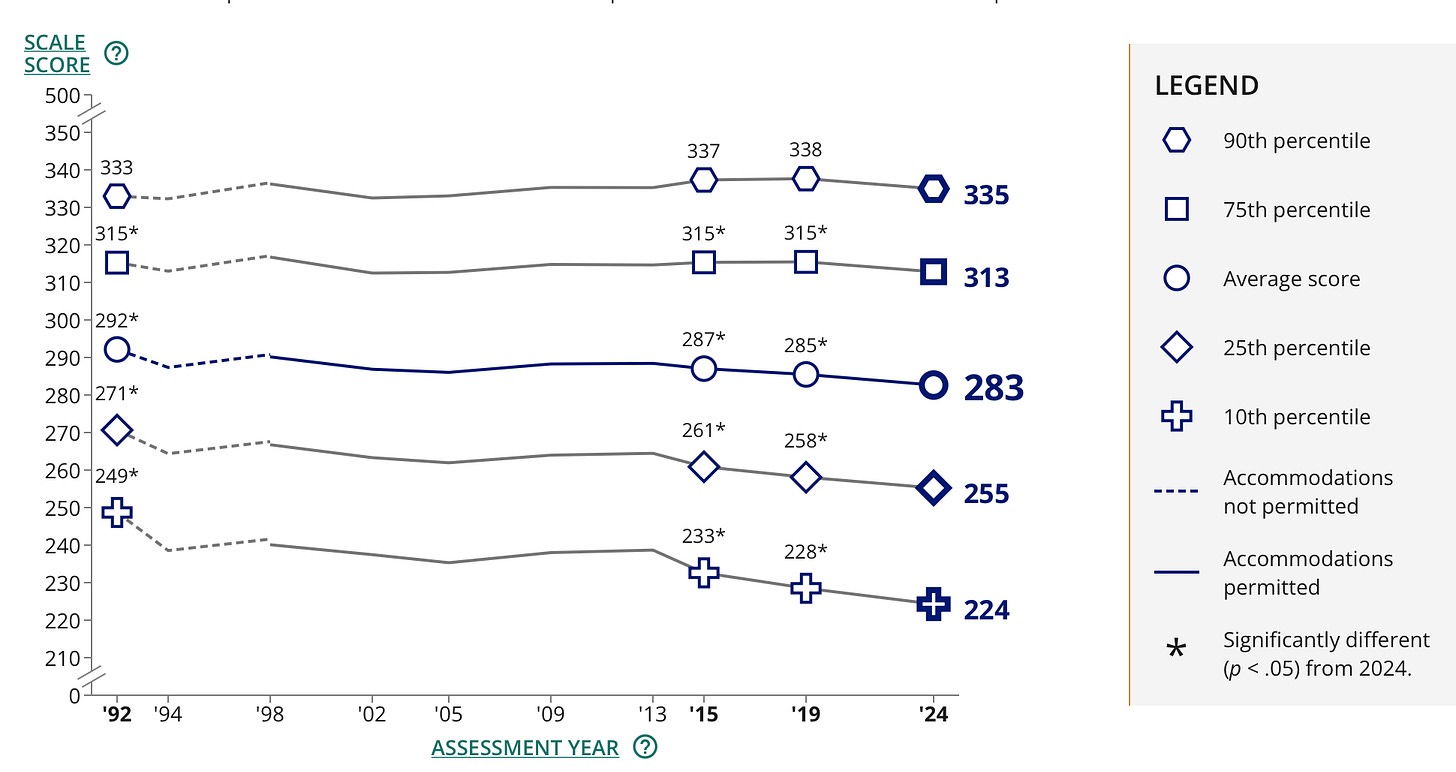

So I genuinely hate to be the bearer of bad news or to complain that some negative information is receiving insufficient attention, but on September 9, we got the latest National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading scores for 12th graders, and they were the worst recorded since 1992.

That’s not good. At this point, I think we all understand that the pandemic badly disrupted schooling and that while this was worst in the places with prolonged school closures, it impacted all kinds of kids in all kinds of places.

But we would ideally be seeing at the national level the pattern that we’ve seen in Washington, D.C., which is that test scores fell dramatically after Covid but are bouncing back. Indeed, by one measure D.C.’s English language arts scores are the best they’ve ever been. But even using other measures or looking at math, where the results are much worse, D.C.’s public schools are at least making headway in recovering from the pandemic. Of course, D.C. had a positive trend in test scores before the pandemic. By contrast, if you look at the national picture, scores were declining between 2015 and 2019 as well, so it’s perhaps not a huge surprise that the decline has simply continued.

No demographic subgroups registered a statistically significant increase. And, as shown in the chart just below, the fall existed across the entire ability distribution — the kids in the lowest percentiles experienced the biggest drop, but even the kids in the top percentiles are doing a little worse than they were 10 years ago.

This situation seems pretty bleak to me. Here is how the NAEP Basic competency level for 12th graders is defined in terms of reading informational texts:

When reading informational text such as exposition and argumentation, 12th-grade students performing at the NAEP Basic level can likely

— use context, typically within close proximity, to identify the meaning of unknown words and phrases

— identify and make judgements about key details within and across texts

— use those details to draw simple inferences about author’s purpose, tone, and word choice

— provide opinions and sometimes support them with generalized text evidence

— evaluate the effectiveness of an author’s claim, organization, and evidence used

— utilize text features and organizational structure to locate information and identify textually explicit details

In other words, about a third of high school seniors basically can’t read prose text at all. They can (I hope) read signs and labels in stores and iMessage each other, but they cannot read a passage of text and understand what it’s saying.

This is really bad! And while there’s been a decent amount written about these latest test results, I think addressing this decline deserves more policy consideration, and space in the discourse, than it’s getting right now.

I think it’s worse here

To be totally honest, Plan A for this post was to look at international data and either show that the decline is a broadly global occurrence (and thus likely due to some global phenomenon like smartphones rather than United States-specific policy choices) or that it was concentrated in the U.S. and a few other countries (and thus likely due to narrow policy choices).

But this question is incredibly difficult to answer.

The best source of information on international student performance is the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests, but the most recent PISA data is from 2022. And PISA 2022 says that student performance suffered a sharp decline in most countries, as you might imagine post-pandemic.

The PISA results are also a reminder of something that I think many Americans don’t know: America’s overall educational performance is above average for a rich country.

Our PISA reading scores were worse than Canada, Ireland, Estonia, and the rich Asian countries, but higher than everyone else in Europe. You used to be able to break out PISA scores by state, which would typically show things like Massachusetts doing better than any European country. But that breakdown is no longer available.

But the main point I want to make about the 2022 PISA is that scores went down in almost every country. One of the few exceptions is China, which I take with a grain of salt because they only provide data for a few disproportionately upscale cities rather than offering a nationwide snapshot the way other countries do.

This confirms that the pandemic was a big deal for education. Notably, it was a big deal for education everywhere. A lot of the best evidence we have that blue state officials did not handle school closures well (see David Zweig’s book “An Abundance of Caution”) comes from the fact that European schools were open. The public health consequences of that were mild, and it’s a good reminder that you don’t need to be some kind of MAGA superfan to see that there was a problem with the most cautious responses. On the other hand, the scores really did go down a lot across most of Europe, despite the schools being open, just as they went down across the U.S.

What I would really like to know, though, is whether other countries have experienced a rebound since 2022, in contrast to America’s continued decline.

The two major countries for which I can find recent national test data are Italy and Japan. In Italy, there was a big Covid-related drop but they are flat in the more recent period while in Japan they are following a similar trajectory to the United States but the declines are less severe.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to get really clear info on this until we get another round of PISA tests. If I had to guess, I would say that when the new PISA comes out, we’ll see that the U.S. is on a worse trajectory than many peer countries. For now, though, that’s just speculation.

Not trying doesn’t work

What we do know is that federal K-12 policy used to place a hefty premium on “accountability” for local school districts. Students were supposed to either demonstrate a solid level of results, or else show clear signs of improvement. If a district couldn’t achieve one or the other, there were supposed to be consequences.

There was significant bipartisan backlash to this accountability regime, and it was dismantled on a bipartisan basis during Obama’s second term.

I find this backlash fascinating. The whole idea of “No Child Left Behind” (N.C.L.B.) had become a big national joke by the time the Every Student Succeeds Act passed and shifted schools away from accountability. Teachers union stakeholders didn’t like N.C.L.B. Conservative decentralizers didn’t like it. Normie high-S.E.S. parents were annoyed at their kids needing to take tests, and normie low-S.E.S. parents didn’t like to hear that their kids were doing badly in school. All around, almost everyone seems to have decided they’d prefer a system that put less emphasis on trying to tell whether kids were learning and taking action if they weren’t.

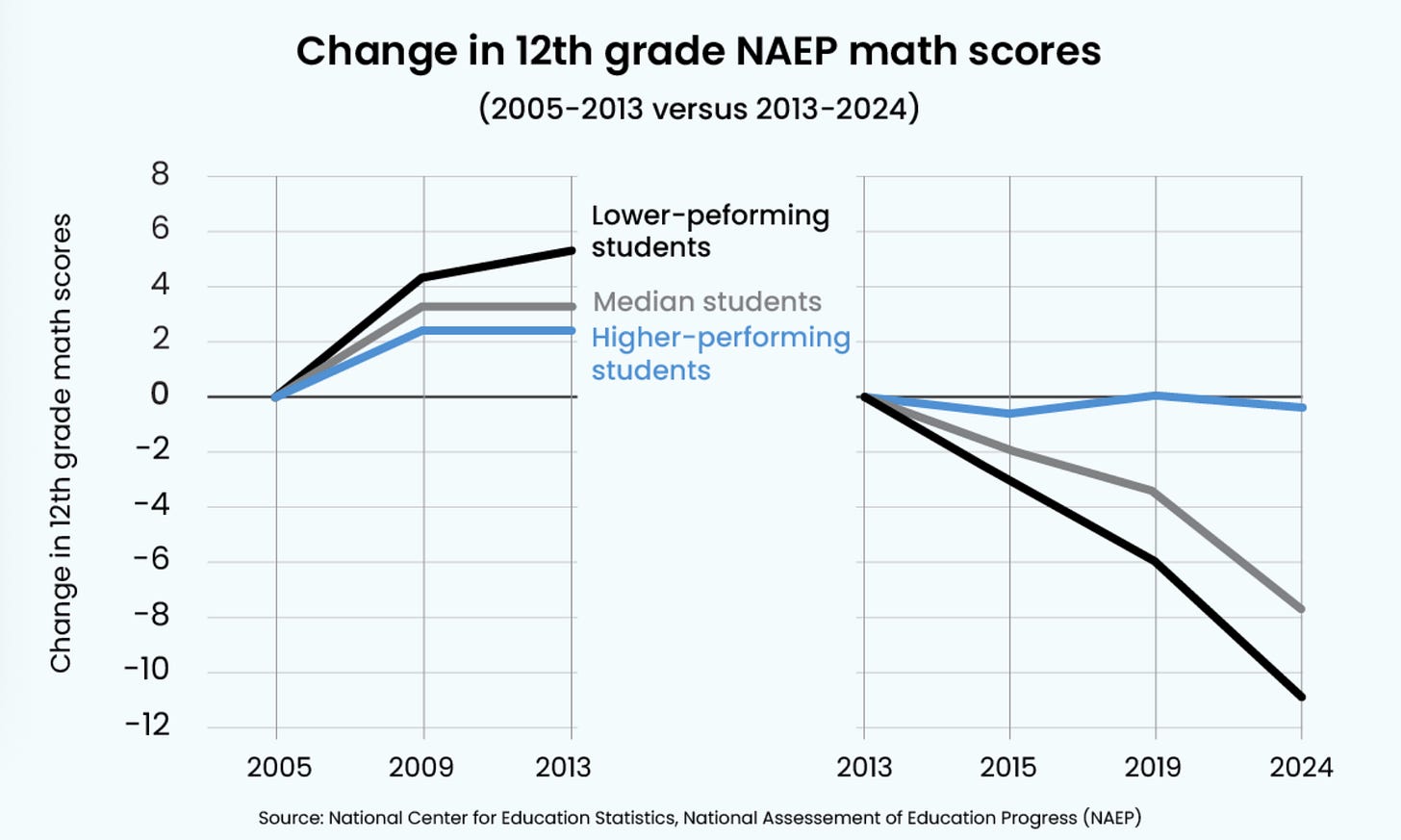

Chad Aldeman makes an interesting point about this. He notes that if you look across the full range of subjects and grade levels, the declines are not particularly concentrated in any specific demographic group, but they are concentrated among the weaker students. The trends for 12th-grade math scores are particularly stark in this regard, but it’s not unique in the history of American education outcomes.

I think this is important because there’s been a huge backlash to heavy-handed “equity” policies in some blue cities, with more and more people suggesting that schools should place more of an emphasis on excellence at the top.

I favor excellence at the top, and I think detracking math education is a mistake. But broadly speaking, in the N.C.L.B. era of accountability at the bottom, all students were improving! In the post-N.C.L.B. era, the best students are doing okay and the weakest students are in crisis.

I can’t say exactly why, beyond the observation that if you were concerned federal focus on accountability for weaker students was holding the strong students back, that doesn’t seem to be the case.

My guess would be that even if schools drop the ball, the best students wind up doing okay thanks to a blend of natural ability, self-motivation, and parental supplementation. But when you hold schools accountable for results at the bottom, they have no choice but to pay attention to instruction methods that work, which has positive results for basically all students.

And I do think these broad structural incentives are important. Karen Vaites writes a great article about the nitty-gritty of literacy instruction. I really enjoyed this one about how the widely used “leveled reading group” system does not work as well as mixing abilities within groups, but then leveling individual reading assignments. Vaites speculates as to why teachers may not be informed about and using best practices. But one might ask the opposite question: Why would teachers be informed about and using best practices? They’re busy. They have a really hard job. If the administrators up the chain are under pressure to deliver results, then they will research best practices and make sure people are using them. But if not, then per another recent post from Vaites, it’s easier to just lower standards.

Similarly, it turns out that a lot of school districts now use reading curriculum packages that don’t feature whole books, just passages. Some people say this is pressure to “teach to the test.” But kids taught this way don’t do better on reading comprehension tests — they do worse. The best explanation, according to Vaites, is that the passages method is cheaper. Of course, if you’re accountable for results, you’re much less likely to just go with the cheapest option. If you’re accountable for results, you go with an option that works.

Exercise for the mind

A telling fact about American education is that 90 percent of American parents believe their child is at grade level, when an accurate assessment would be about a third of that.

Aldeman notes that this is partly a policy issue. School districts conduct assessments in the spring, but often wait until fall to tell parents how their kids did. He’s right that this lag doesn’t make sense and should be fixed. However, it clearly also reflects a certain amount of parental incuriosity and optimism. And we’re seeing, I’d guess, an inclination on the part of classroom teachers to be people-pleasers rather than deliver bad news to parents. But that in turn reflects the reality that a large share of parents want to hear positive things about their kids and their school more than they want accurate information.

That’s understandable; I also like it when people say nice things about my son.

But it’s almost impossible to get good performance without measurement. And with reading in particular, it feels to me like whatever’s happening in school, we’re also living through a national collapse of interest.

I am actually quite sure my kid is above grade level in reading because Kate and I make sure he spends a good amount of time reading almost every day (and also because teachers at his school are good about sharing assessments multiple times per year). And while a lot of the books that he reads are either kid-centric books or easy-to-read Y.A. fantasy, some of them are books that we suggest to him as challenges. It is more difficult for him to read more challenging books (obviously), but he can, in fact, do it and he does, at least a little bit, every day.

And pretty much everything in life is like this. I’m not someone who enjoys exercise, but if I skip it for a while, I get horribly out of shape. So I really try to drag my ass to the gym every week.

I recently joined a new one and, as part of a prescribed workout, got to do some comically easy bench presses. That was fun; I like that a lot more than working hard. But there’s no real point in that — you have to do things that are difficult or you don’t get any better.

I’m also trying this year to be much more intentional about my own reading by prioritizing whole books of fiction over nonfiction stuff on the internet for work or quasi-work. I’m really good at skimming informational content, which is part of how I do this job. But precisely because I’m good at it, it’s better exercise to do the other thing and work on my attention span. A lot of that is fun thriller type stuff (I’m working my way through Paul Doiron’s Mike Bowditch mysteries), but I’m also reading “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall” and thus finish the complete works of the Brontë sisters.

On some level that’s a bit far afield from the education policy questions, but I think it sort of all relates. Of course there are extrinsic factors at work — digital distractions, a pandemic, often troubled home lives, etc. — but on some level we’re suffering mostly from a big national failure to take the educational goals of the school system seriously. As I wrote in the inaugural issue of States Forum over the summer, this is particularly egregious in the bluer states, where the levels of spending on K-12 education are much higher but nobody wants to ask the basic questions about whether appropriate curriculums are in use or whether schools are doing a good job. It’s possible that because of AI, education will become less economically important in the near future. But in some ways that only makes it even more urgent that we avoid a situation where everyone gets mentally flabby, just zoning out to short-form video all day.

In a sane world, we’d just ban short-form video. Or tax it in inverse proportion to its length!

Short of that, we should stigmatize it. Short-form video should be disdained like a hard drug.

If YouTube is like alcohol, TikTok and Reels are cocaine.

What’s left out here in terms of the dramatic drop in low performing student scores is the explosion of “school refusal” and chronic absenteeism. In NYC we have 1/3 of students who qualify as such.

I’ve spent 12 years as a frontline home and community-based Social Worker and watched what happens when we defanged child protective services for the sake of “equity” and fighting “white supremacy.” It used to be the case that if a kid was chronically absent eventually the caregiver might have to answer to a court, but would at least have workers in the home, addressing it and taking it seriously. This may have seemed heavy handed, but the removal of any interest or interventions on the part of the child welfare system to address educational neglect certainly corresponds to these trends. Not to mention the fact that usually Ed neglect was an indicator of larger problems in the home, which we then had the ability to address.