America's "crumbling" roads and bridges are fine

Let's do the broadband and grid and water stuff instead

This post is a free edition of Slow Boring, a daily blog and newsletter about politics and policy. If you like what you see and want to read more, please consider buying a subscription. Discounts are available for government workers, students and educators, or for those willing to make a small group subscription. If you’re not yet ready to commit, you may enjoy some of our other free posts like “Meritocracy is Bad” or “17 Theses on Pete Buttigieg and the Department of Transportation.”

There is a lot more happening in Joe Biden’s American Jobs Plan than just throwing money at America’s crumbling roads and bridges. And it’s a good thing, too, because after years of being mildly annoyed by this rhetoric, I’ve actually been researching it and it’s basically a huge myth.

Not to say that there are zero roads or bridges in the United States that could use a little repair.

But there’s just no reason to believe that the existing surface transportation funding levels in the United States are inadequate. We have some of the best commute times in the world in an international context; our road quality is improving under current funding levels; and the biggest practical problem we have — endemic congestion in a few key metro areas — is not really amenable to being addressed with a big surge of funding.

Mitch McConnell complained that Biden’s plan “is not about rebuilding America’s backbone. Less than 6% of this massive proposal goes to roads and bridges.”

That seems like a severe undercount. But McConnell is correct that a majority of the stuff in this plan is not about roads and bridges, even though progressives seem eager to highlight the roads and bridges stuff.

And it’s a good thing, too, because the roads and bridges are fine!

America’s transportation outcomes are pretty good

There are areas in which the United States is a laggard in international terms. Our relative child poverty rate, for example, has long been extraordinarily high. The refundable Child Tax Credit that’s being created for one year in the Biden Rescue Plan will greatly improve that situation. Making it permanent would do an enormous amount of good, especially if paired with administrative reforms to the design of the program that would increase its uptake.

Other problems in American life that really stand out to me:

Despite improvements over the past decade, Americans are exposed to an unacceptable amount of idiosyncratic financial risk thanks to our threadbare health insurance system.

Americans’ per capita levels of greenhouse gas emissions are the highest of any large country in the world.

The United States has a much higher murder rate than the typical rich country, and it also suffers from elevated rates of suicide and drug overdose deaths.

The child care cost situation is really bad, in a way that strongly impacts middle-class families, and that’s the major driver of Americans having fewer children than they say they want.

The United States has come to be an international laggard in the share of its prime-age population (i.e., people between the ages of 25-54) that has a job, even though the whole point of America’s unusually weak labor marker protections is supposedly to encourage employment.

By contrast, as mentioned, we have some of the best commute times in the world.

That’s not because American infrastructure is perfect in every way or anything. I have written many times about the gains we could make by learning from German mass transit operational practices. But as readers of “One Billion Americans” will recall, the contiguous United States has one-sixth the population density of Germany. So while American mass transit is worse than Germany’s, it’s also much less important to America than it is to Germany.

Related, the very worst metro area for commute times is East Stroudsberg, PA, which basically reflects people taking unreasonably long journeys into New York. Second-worst is the New York metro area. The fact that American mass transit is bad is definitely a big deal in Greater New York and it shows. But in general, Americans have easy commutes. The Swedes, best in the world, use congestion pricing in Stockholm which New York is now poised to adopt, and which the other Bad Traffic Jam metros (D.C., Atlanta, San Francisco, and the LA/Inland Empire zone) should copy.

America’s roads are good and getting better

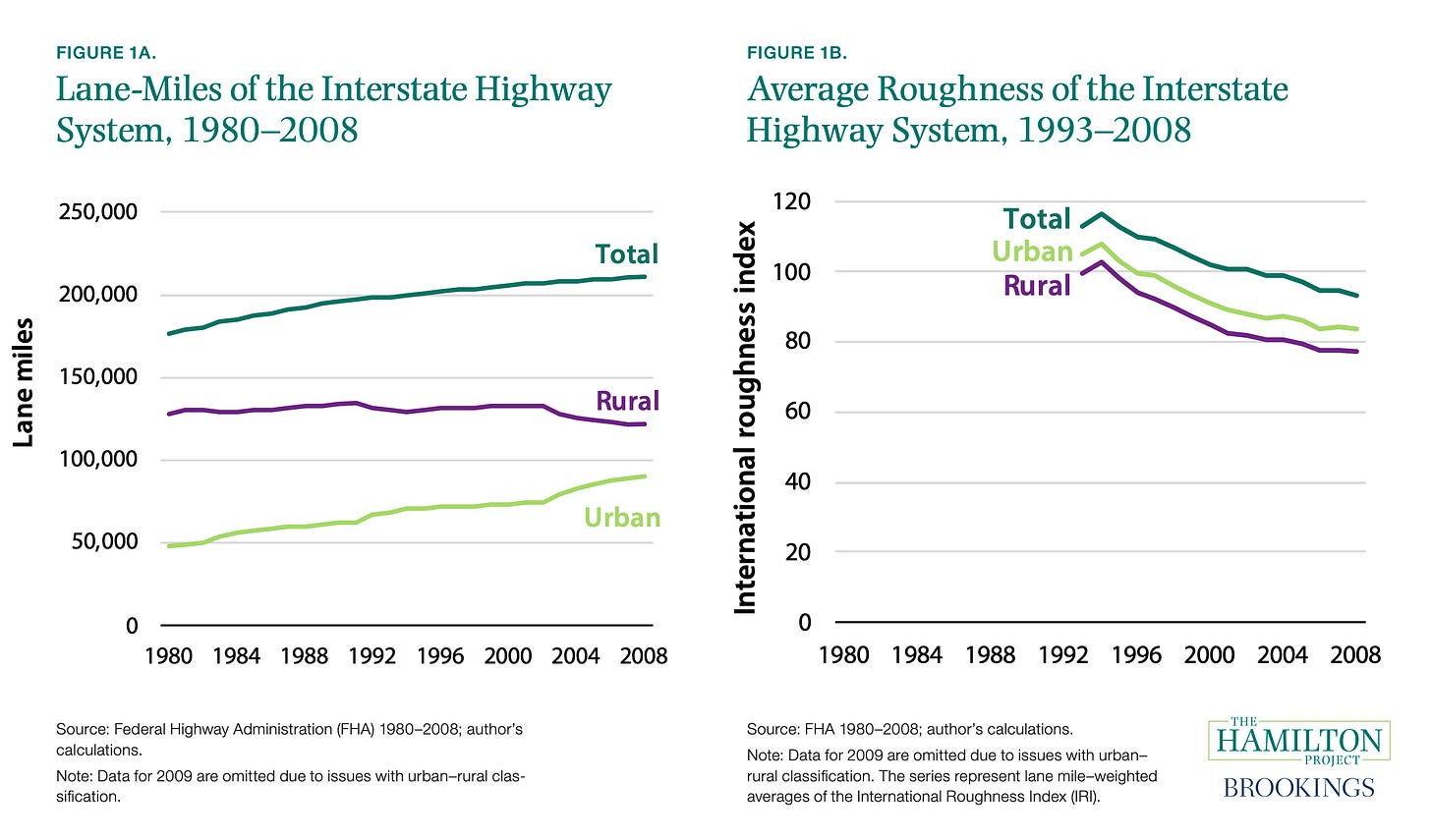

Back in 2019, Matthew Turner did a report for the Hamilton Project that has some eye-opening facts about America’s roads. Facts like “they keep getting better.”

That’s not to say we shouldn’t spend money on roads. But I think it does strongly suggest that our basic ongoing level of road funding is fine. What we are currently spending is enough for the interstate highway system to steadily expand while simultaneously improving in quality.

Now to be fair, that data is pretty old at this point. But conveniently, the American Society of Civil Engineers that’s always arguing for more infrastructure spending did a report in 2009 where they gave our roads a D- grade. In this year’s report, we are up to a D!

Could things be even better? Sure, probably.

But here’s something that I think is telling. Traditionally, the United States funded highway spending by collecting gas taxes as a kind of user fee. But the gas tax was last raised in 1993, and its real value has stagnated since then. Everyone seems to agree that raising it further is politically unviable. There has been some brief discussion by pointy-head types in both parties of creating a new Vehicle Miles Traveled tax to fund roads, but once it became clear that Biden was not doing this in a bipartisanship-seeking way, his team dropped that idea really fast.

This all seems like smart politics to me. But it’s smart politics with a message — the message is that America’s driving public is happy enough with the quality of the roads that they don’t want to pay any extra money for the sake of improving them.

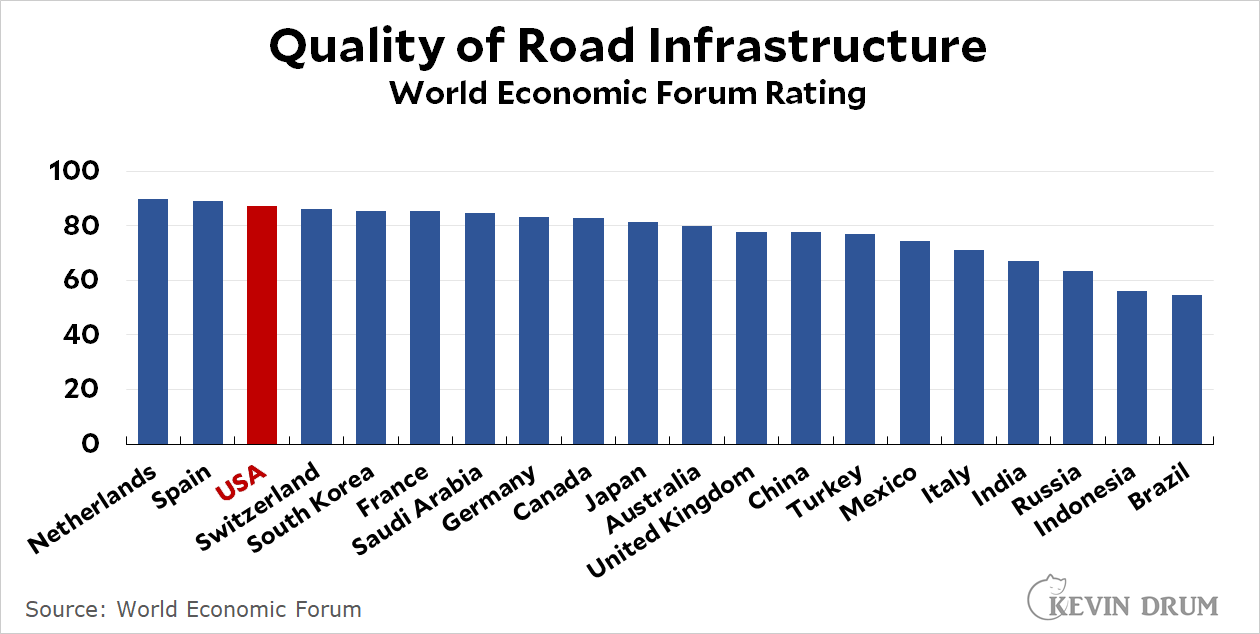

As Kevin Drum notes, the World Economic Forum surveys say that America has some of the best roads in the world. Our bridge failure rate is also normal and fine.

I live in a walkable neighborhood in a reasonably transit-oriented city. My daily commute is down to my basement where Slow Boring Headquarters is located. My kid’s school is literally across the street. So neither bad roads nor higher taxes on driving would impact me very much. And if you were telling me that creating a new VMT to take our roads from “better than Switzerland” to “better than Spain” is wildly popular, I’d have no problem with that. But everyone thinks it would be politically toxic.

And why shouldn’t it be? The roads are fine!

The costs sort of matter here

Interest rates are low right now, so I don’t really have a problem with the federal government doing something mildly wasteful like borrowing money for an unnecessary highway surge.

But Biden is promising to offset the cost of his Jobs Act spending with long-term tax hikes on the rich, which means we’re having a different kind of fiscal argument — redistribution. Redistributing money from rich people to highway contractors is not the worst idea in the world. But it’s also really not the best idea in the world. And there are limits to what kind of tax increases are politically or economically feasible. For Democrats to waste the low-hanging fruit of the tax increase world on road upgrades when it could go to pay for a permanent reduction in child poverty would be a mistake.

And I particularly want to stake out this point early in the Jobs Act debate because laws tend to change as they work their way through the congressional process.

The odds are pretty good that this bill will either be scaled back somewhat for whatever reason, or else that key players in Congress will want to include something that wasn’t in Biden’s proposal, which will force something else to be taken out or scaled back. That means it matters a lot which elements of the Biden plan are seen as essential and which are just okay.

As a reminder, the plan breaks down like this per Alyssa Flowers’ great summary graphic for the Washington Post:

When I look at this, my favorite parts by far are the “hard construction projects that aren’t transportation” bits — mostly what Biden is calling infrastructure at home, but also the electric vehicles and infrastructure resilience. I’m convinced that these are real problems. But more than that, they are real problems that can be greatly ameliorated by simply throwing money at the problem. In housing, though, you also need reform, and the plan calls for smart reforms.

I would hate to see any of this $600 billion taken out, shrunken down, or messed with.

Then you have the industrial policy stuff (R&D and Manufacturing on this chart) and the care economy stuff. Both of those deserve separate consideration, and I’m still working on improving my understanding of exactly what Biden’s proposals do. But at the level of “identifying problems,” these are two very legitimate targets for policy. The long-term care situation that currently exists in America is really bad, and spending money on fixing it makes sense. Research is great. And the pandemic has reminded us that paying attention to supply chain issues matters.

So if I were to cut something, I’d take the opposite of McConnell’s suggestion and cut the roads and bridges. Ever since the 2012 and 2015 highway bills, we’ve been routinely pumping more money into the road system than it generates in gas taxes, and I don’t think more cross-subsidy is the answer to any big problems.

Fixing traffic congestion

None of this is to say that we should be totally complacent about the long commute situation in the handful of big metro areas where America really does have substandard commute times.

I just think it’s important to acknowledge that pumping more money into the existing highway system is not really going to fix our problems here.

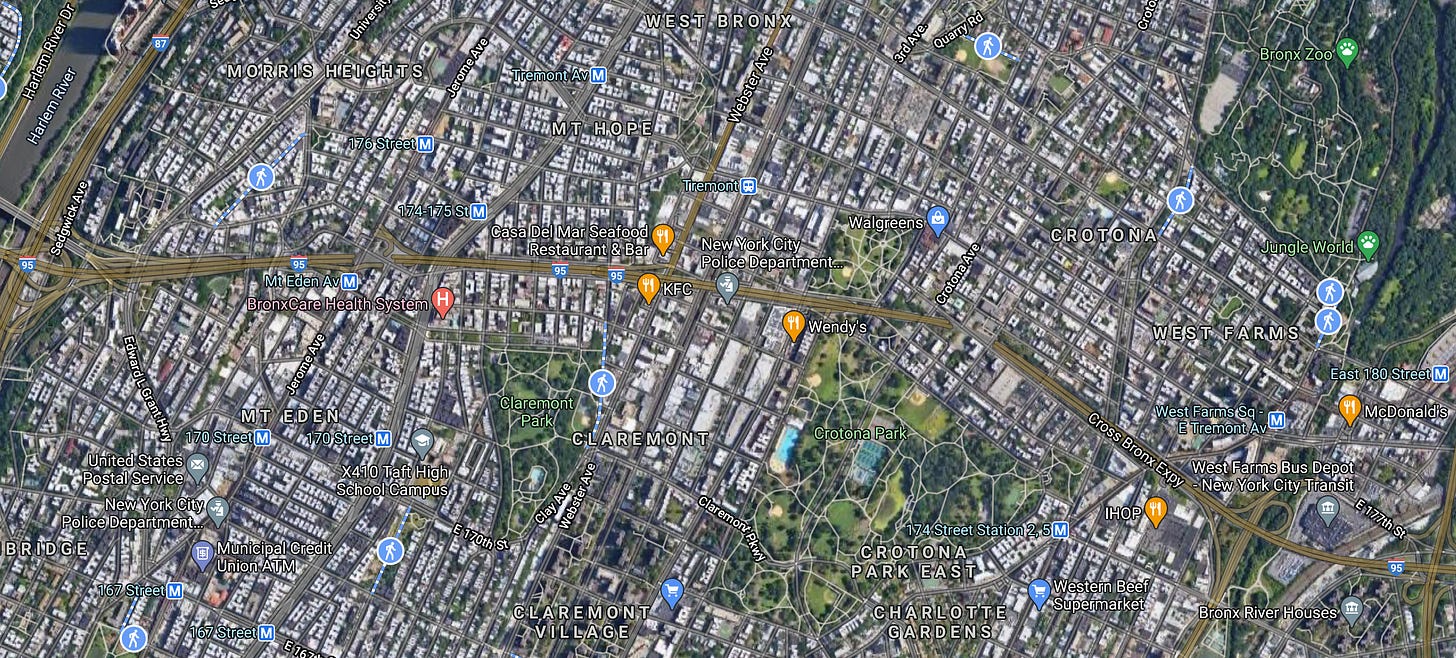

Some of this is just basic geometry. I think the “crumbling roads” narrative gets a big boost from the media’s hyper-concentration in the Greater New York area, where the roadways really are ancient and awful. But what, realistically, are you going to do about it? Check out the Cross Bronx Expressway, one of the most cursed highways in America — it runs smack through an incredibly dense series of residential neighborhoods.

People tend to underestimate how much denser New York is than everyplace else in America, but the Bronx is more than 50% denser than San Francisco and nearly triple the density of Washington, D.C. You can’t just widen this highway. The real problem with it and similarly terrible NYC roads like the BQE and the Belt Parkway is that they should never have been built in the first place. Dismantling them and turning them into regular surface streets and housing is probably not going to happen. But you can’t really “fix” them.

The logistics in the D.C. and LA areas are not as bad (I’m not familiar with Atlanta, but Kevin Kruse’s article about Atlanta freeway building is very interesting), but they both do an excellent job of illustrating the basic limit of “build more roads” as a solution to traffic problems.

The basic idea here is called “induced demand” — you build more roads so people drive further. I am not an induced demand fanatic, and I think sometimes the Ban Cars crowd takes this logic too far. But Southern California does illustrate it well, because one of the longest commute-time metro areas in the country is what the U.S. government calls the Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario metro area. Nobody actually talks like that because it’s obviously not a real city at all. It’s just that commuting and housing affordability in LA got so bad that the city wound up spinning off this whole second metro area where the traffic is also bad, and yet you’re so far away from everything that your commute is even longer than in the original LA.

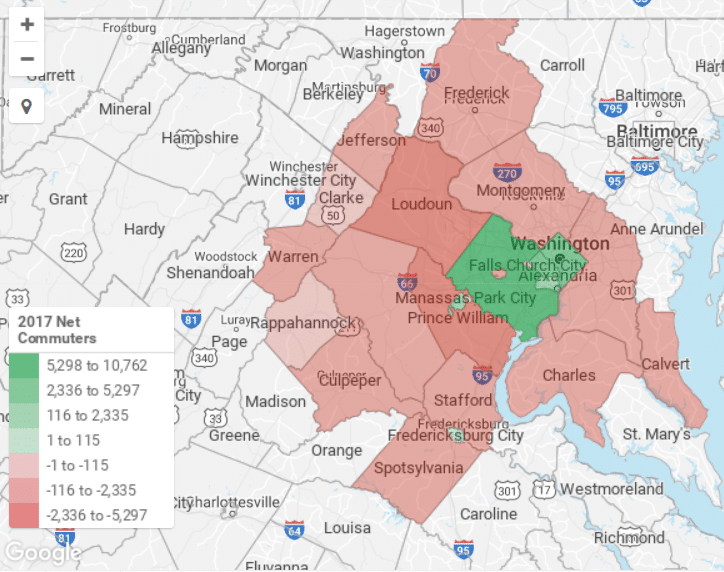

The D.C. version of this is that thanks to heavy investments in road-building by Maryland and Virginia, we now have plenty of people commuting in from Frederick and Fredericksburg — two similarly named cities that are very far away from downtown in opposite directions.

In an earlier phase of my life, I was an anti-sprawl fanatic who thought this was just terrible. I’ve mellowed in my old age, and to an extent, if American states want to build really sprawling cities that’s fine. But it fails as a specific solution to the traffic jam problem.

What America’s bad traffic cities really need is congestion pricing, zoning that allows more people to live in convenient locations, and selective investments in improving mass transit capacity.

Good transit spending would be good

Biden’s plan does have money for mass transit, which is nice to see.

But even though the transit advocacy community doesn’t see it this way, I think it’s important to be clear that lack of money is not the main problem with American mass transit. I’ve written a few times about transit construction costs and scope creep. But there are also just fundamental questions about planning.

Los Angeles, for example, has now built about 97 track-miles of LA Metro Rail, which is only a tiny bit shorter than the Chicago L. But almost nobody rides. And, yes, that’s the history of the city’s built environment — but the ridership figures are comically low. The Lyon Metro is only 20 miles long, serves a metro area with less than a third of LA County’s population, and has double the daily ridership. There’s something fundamentally ill-conceived about a project that involves that much building for so little actual usage. Some of those are problems with route selection, but the biggest issue is that even as Los Angeles built out their transit infrastructure, they didn’t change land use policy to encourage dense development near the stations.

Even New York City has under-used subway capacity in some parts of the city where they could locate more development, and metro areas like D.C., Boston, and San Francisco have plenty.

If you’re actually being smart about your project selection and land use, then more transit spending is incredibly valuable. But the lesson of LA Metro, to me, is that you can’t just brute force yourself into transit usage by spending a lot of money. People aren’t going to ride the train just because you would prefer there to be fewer cars on the road. It happens either if people are too poor to afford cars (not the case in the United States) or else if it’s a convenient way to get someplace that has scarce and expensive parking. Without that land use alignment, it’s pointless. And urbanists shouldn’t tell themselves that all this highway money is fine because the transit spending is also generous. If the transit and highway stuff both shrinks, that’s fine by me. From a transit point of view, the important part of this bill is to get the housing reform money and to design that program well.

But at the end of the day, the overall point is that America’s transportation infrastructure is pretty good. By contrast, the same low population density that generally makes our commutes good has left us with subpar levels of mass broadband adoption. The challenge of moving electricity around is very real. Lead in water pipes is really bad. These infrastructure challenges are huge and much more important than roads and bridges. If the bill gets changed, it’s important to keep that stuff.

This is a good post, but I'm not sure bridge failures are the best measure of bridge quality. I'm a bridge engineer and some of the talk I've seen in the industry is more about aging bridges and maintenance costs, basically that inadequate funding for preventative maintenance ends up costing more in the long run. If your maintenance budget is too small then bridges that could have been maintained inexpensively turn into bridges that need expensive repairs ten years from now. The poster child used to be the Greenfield Bridge in Pittsburgh that was crumbling so badly they constructed nets and a smaller bridge underneath just to catch debris. That seems like a good chunk of money that could have been put to better use.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenfield_Bridge

Just want to add a disclaimer that though I'm a bridge engineer I know very little about the national condition of bridges so I'm not trying to speak from authority there, just mentioning what I've seen in seminars and such.

I think the NYC-centrism of the American publishing industry feeds into this a lot, because as you note the BQE really is crumbling, and the general road quality in NYC really is terrible.

But NYC’s roadway maintenance problems are largely administrative and occasionally simply criminal. The various city agencies involved don’t coordinate maintenance timelines so replaced roads sit for weeks without lane markers, milled out roads take weeks to get new asphalt poured, recently resurfaced roads get dug into for utility maintenance, and certain favored neighborhoods get their roads resurfaced regularly while the Bronx rots. And of course sometimes scheduled work just mysteriously doesn’t happen. (Bike path maintenance happens halfway to never, of course.) None of this can be solved by increasing he NY DoT’s resurfacing budget, although increasing the federal DoJ’s appetite for municipal corruption cases frankly might help.

Also I’m not so sanguine that the BQE is going to be rebuilt any time soon. The much more likely scenario to me would be a replay of the fate of the original West Side Highway: a section of it is going to collapse (everybody is worried about the cantilever along the Brooklyn promenade but don’t discount the possibility of one of the concrete supports under the southern stretch through Sunset Park giving way and killing a lot of people in the process) and it’ll sit closed and condemned for a decade or more as lawsuits fly back and forth.