Here’s a kind of banal idea that I’ve been thinking about: the rich donors and well-endowed foundations who fund policy analysis and advocacy organizations in D.C. ought to put more emphasis on things like “try to come up with the correct answer” and “explain the truth in a clear way” and less emphasis on being a good team player.

One particularly striking example of this is the child care subsidy proposal that was part of the Build Back Better package. The genesis of this legislation was a 2015 proposal from the Center for American Progress to create sliding-scale tax credits to defray the cost of child care. Over time, the proposal became more generous (capping costs at 7 percent of income rather than 12 percent) and accrued various pro-labor provisions, as well as a plan for a multi-year transition from the current unsubsidized system to the new permanent vision. The problem, as Matt Bruenig pointed out (see more here and here), is that the transition plan was very poorly structured and would have pushed the cost structure of child care up before the subsidies kicked in, leaving tons of middle-class families worse off. Democrats eventually scrambled to tweak the proposal, but BBB’s family provisions became a tangled mess of phase-ins and phase-outs, and eventually the whole thing died on the vine.

But how was it that nobody noticed this problem until Bruenig? I heard from someone who used to work at a well-regarded center-left think tank that one of her colleagues noticed this exact problem earlier. But when she raised the issue, she was told to keep quiet because the care groups have always been supportive on other issues.

That is the most explicit statement of Coalition Brain that I’ve heard, but I think it’s a widespread syndrome across causes and institutions. Everyone is supposed to mind their own business and support the team, not directly fire at anyone else. And of course it’s true that politics is fundamentally a team sport and a game of coalitions. But I think two problems arise when Coalition Brain gets too severe. One that I’ve talked about a lot is that while you avoid nasty fights about prioritization, you also wind up not actually setting priorities. To set priorities, different groups need to be able to criticize other groups’ ideas and say that the other group’s proposal is actually not very well-designed, addresses an unimportant topic, or for some other reason is a less-worthy use of a limited budget. But the other is probably that the journalists and elected officials who depend on the groups to develop policies can end up with an exaggerated sense of the policies’ merits.

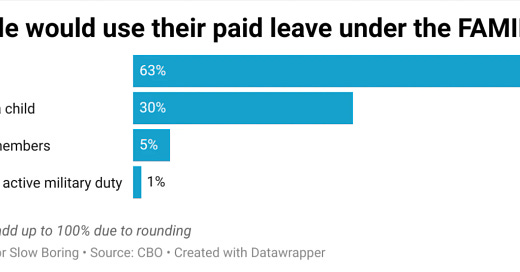

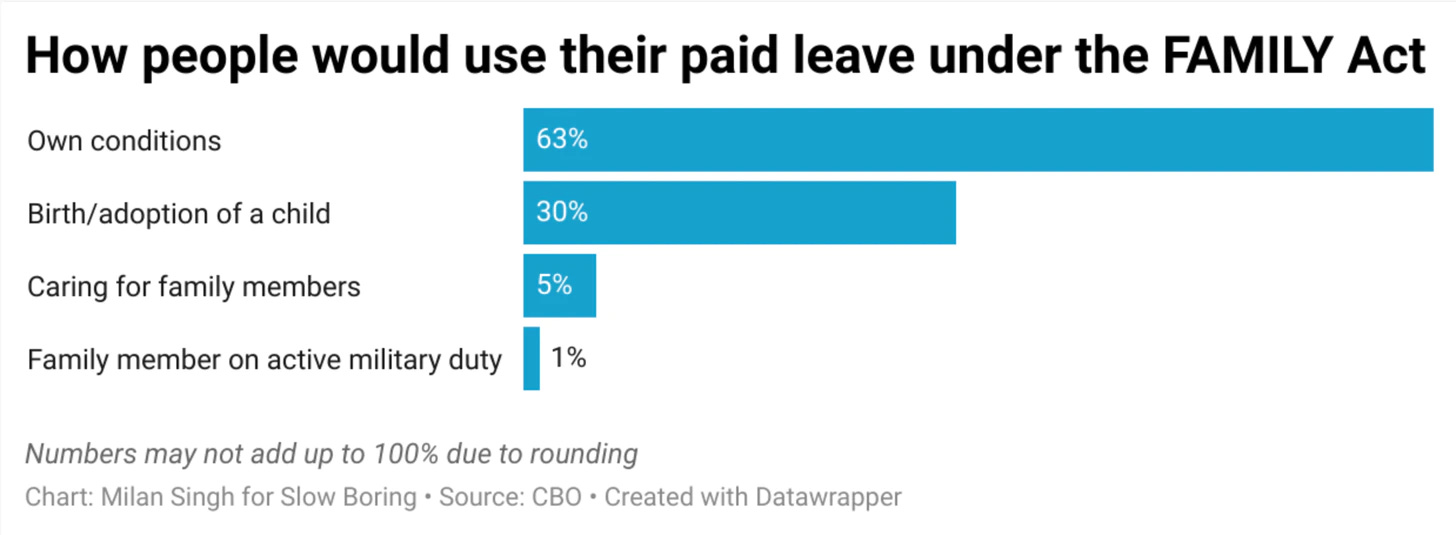

I remember showing this chart about Democrats’ paid leave proposal to a friend who works in political journalism. She was genuinely very surprised — she thought the proposal was for universal parental leave and had no idea that over 60 percent of the benefits were for personal sick leave or that 30 percent of new mothers wouldn’t qualify for coverage.

After that, I surveyed some members of Congress and chiefs of staff I know on the Hill, and about half of them didn’t know either. This was not secret information — it was in the CBO score — but the fact that Democrats had so little information about the content of their own policy was a sign, I think, of how impoverished the policy debate has become. Nobody was out there making the case that “hey, the part of this that people are fired-up about is the leave for new parents, let’s narrow the bill but make the coverage universal and it’ll be cheaper.” And because nobody was making that case, nobody was making the affirmative case for the structure they decided on.

There was no debate at all, nobody kicking the tires on the policies — just siloes moving in tandem as a coalition.

Misreading the Obama years

Think tanks have always had one foot in the propaganda game, and I think that’s honestly appropriate.

But there’s a big difference between one foot and two feet, and I do think there’s been a big change here to the point that I often struggle to know where to point a younger journalist seeking reliable sources of information. If you’re old like me, sometimes people you’ve known for a long time will tell you things quietly. But when I was in my early-to-mid 20s, I really relied on policy groups having overt arguments with each other in order to learn about the issues.

I think a lot of the change came from the fact that Barack Obama and his team had a really solid “earnest wonk” brand, and so when people grew disappointed with the limits of what they were able to achieve, they decided that this showed that technocrats had failed and a whole new approach was needed.

But I never thought that made sense as an account of what went wrong under Obama. The biggest failure of his administration, by far, is that they left the economy under-stimulated. But this was a failure to listen to the technical analysis. Christina Romer calculated the size of the output gap, Obama’s team decided they couldn’t ask Congress for that much, and then Congress gave them less than they asked for. But the actual technical analysis was fine. They relatedly failed to fill the vacancies on the Federal Reserve Board in a timely manner, which delayed the arrival of useful monetary stimulus. But that is a very tedious technocratic failure, not some kind of “listened too much to the policy nerds” thing.

The other issue is that a lot of people came away from the ACA experience feeling disgruntled about all the blood, sweat, and tears wasted on an unpopular and ultimately unnecessary and repealed individual mandate. This is a more nuanced issue. I always felt the mandate approach was a mistake going back to 2007, and back when Obama was taking criticism for being anti-mandate, I defended him. But the specific problem with the mandate turned out to be that because it was unpopular, congressional Democrats made it too weak to work as designed. This strikes me, again, as mostly a failure to listen to the wonks, not the wonks running amok.

But the dominant interpretation was that Obama showed us the limits of technocracy, so we were going to go in another direction next time. This was paired with, I think, an exaggerated sense that party-line votes are the only way to do policy and an overestimation of how much party-line stuff can really get done with a narrow congressional majority. So everything went all-in on The Coalition Over Everything.

Beware easy answers

Rigorous policy analysis is moderately difficult to actually do, certainly more difficult than cheerleading.

And it’s always tempting to convince yourself that the easy thing is also the correct thing. Even for someone who is capable of rigorous analysis, most people find it more pleasant to get along than to have fights. So it feels easier to say that the right thing to do is not point out that the Brennan Center’s work on democracy reform doesn’t make very much sense or to note how odd it is that Democrats devised completely different structures for their pre-K program (i.e., care for three- and four-year-olds) than for their child care program (care for one- and two-year-olds), which is also totally different from their paid leave program (care for zero-year-olds). The reason there’s no coherence is that these proposals were developed by different people, and those people just had different ideas.

In a competitive policy development framework there might be some consideration of which design is best, and then perhaps the best design is extended to all aspects of the program. Or else we might have a bipartisan policy dynamic where the question is which design is most appealing to Lisa Murkowski. Or we might have a prioritization conversation where the question is which one of these ideas is best suited to go right now.

But instead, the thinking was that nobody needs to subject these ideas to any scrutiny and nobody needs to ask any questions, because we’ve got the 50 votes so why not just do it all?

This turns out not to work so well. Simply refusing to prioritize doesn’t change the fact that building a full European-scale welfare state would require very large, politically implausible tax increases. The reality is that (a) there is only going to be so much change in any given period of time and (b) you are often working with very kludgy policy designs structured to minimize explicit tax increases. Under the circumstances, you really don’t want to waste the bandwidth that (a) provides by fighting for programs whose messy design due to (b) renders them actually not very useful.

There is unfortunately no really good alternative to getting the analysis right all the time, showing good judgment, and enacting policies that are actually good — just as making ARRA too small and having an understimulated economy was bad, making ARP too big was also bad. It is genuinely difficult to govern effectively, and that means that para-party groups need to do the difficult work of hiring genuinely smart people and supporting them in efforts to do genuinely rigorous work.

Big, important tasks are often just difficult.

The return of tradeoffs

I’ll return to this theme in the coming weeks, but having an inflationary, fully-stimulated economy for the first time in the 21st century changes something important — it means facing tough tradeoffs.

President George W. Bush enacted two separate rounds of regressive tax cuts. You might have thought that would come at the expense of domestic social welfare, but he also signed a bipartisan bill to expand Medicare benefits and he expanded SNAP eligibility. Bush was ideologically committed to welfare state rollback, and he didn’t manage to accomplish anything on that front. But he did preside over two separate medium-sized wars, plus a large increase in the baseline budget, plus various increases in homeland security and law enforcement spending. His Democratic critics, at the time, kept insisting that this was irresponsible and something would have to give, but we never really got to that point.

To be clear, Bush was a terrible president and an object lesson in the importance of good policy design. But in his case, the specific terrible things that resulted from his very shaky policy ideas were a couple of military disasters, bad oversight of the banking system, and a paralyzing failure to act decisively as the economy was collapsing. Fiscal policy tradeoffs never materialized. Obama operated under much tighter political constraints with regard to the budget, but they were purely political. Nothing Congress spent money on during the Obama years had to come at the expense, economically speaking, of anything else. It was all stimulus and all dominated by politics. And then Trump came in, returned us to Bush-style budgeting, and also did lots of crazy trade policy stuff. Plenty of folks insisted those trade moves would be ruinous, but the economy was still depressed enough that introducing inefficiencies into the system wasn’t really a big deal. America is paying a price for Trump’s trade policies right now, and dropping tariffs is something Biden could do to fight inflation. But at the time, tradeoffs weren’t that big of a deal.

Today, we have full employment, which is great. But we also have inflation, which is less great, and that means everything has tradeoffs. When you spend $1 billion on X, you can’t spend it on Y. Or if you do spend on both X and Y, that is inflationary. Targeted student loan relief to help those in need could be a good idea, but the more student loans you forgive, the more inflation you’ll generate, so you need to think carefully about what you’re doing. Loan relief for recent law school grads will directly press up housing costs for working-class renters; you can’t just call it all stimulus.

This return of tradeoffs raises the value of sound policy analysis because it raises the bar for what’s actually worth doing. I don’t necessarily think we should do big cuts to our military budget, but we absolutely need more scrutiny of what weapons systems we are buying and what missions we are undertaking in a world where we both have legitimate defense needs and also can’t just write the military blank checks. And on the domestic front, we need to solve problems with good ideas, not assume there’s no harm to waste. It’s a brave new world and it requires a better class of policy analysis.

Live by the omnibus bill; die by the omnibus bill. We have lost a lot by trading committee work on understandable bills for total leadership control. Maybe the secret congress still does some of the old style of lawmaking, but it seems that spending bills are now strictly partisan and they are worse for it.

This is where it would be helpful to have a Conservative party and media apparatus with real ideas around government, rather than one that solely exists to trigger the libs.

There is a legitimate crisis in state capacity across our government. To name a tiny example, it takes the IRS 18 months to answer a letter. The Democrat solution is to septuple the IRS budget to hire auditors to chase down minor tax discrepancies. The Republican solution is to abolish the IRS. How about we just have a party that tries to get them to open the mail punctually and go from there?

Same problem exists wrt 3 year immigration court waits, 9 month passport turnaround, continued shutdown of social security services. Small c conservative good governance is highly in demand right now!

I might not always (ever?) agree with a more serious Conservative party, but it is unhealthy for that role to be played solely by Joe Manchin and Susan Collins across the entire government.