Recent layoffs at Big Tech don't spell economic doom

They could even be change for the better!

On January 19, Vox’s Emily Stewart wrote a good piece about how widespread layoffs in the tech and media sectors don’t necessarily foretell broader problems in the economy. The next day, Vox Media announced layoffs of approximately 7% of the company’s staff, which some people used as an opportunity to dunk on Stewart.

The truth, though, is that the widespread attention given to the Vox layoffs illustrates her point.

Some of the people who lost their jobs are people I know, including people I worked with for years, and I’m incredibly sad to see them lose their jobs. And because we’re talking about 150 media professionals — each of whom knows lots of other people who work in media — many thousands of journalists with national audiences across a wide range of outlets are also sad about recent layoffs, which haven’t been restricted to Vox.

And with so many journalists reacting to this, I think it can be difficult to maintain a sense of the scale. Consider that Kroger has about 465,000 employees across 2,720 supermarkets, or about 170 workers per supermarket. Some of those employees are at corporate headquarters, but a Kroger closing is approximately the same number of jobs lost as Vox Media laying off 7% of its workforce. A Kroger closing would be a big deal to the people who lost their jobs and to the neighborhood where the store was located, but it wouldn’t be a national news story. Last week someone told me there used to be a Safeway in their D.C. neighborhood and that its relatively recent closure has been inconvenient for their life. But the closure isn’t even a news story that reaches someone like me who lives on the other side of town, much less someone who lives in a different metro area.

The media industry is an extreme outlier in terms of attention paid versus objective economic significance.

But it’s not unique. Amazon, Salesforce, Meta, Google, and other tech companies have also been laying off employees and are also examples of companies whose cultural footprint outpaces their actual scale. As far as anyone can tell, the overall labor market remains quite strong. And indeed, given that the labor market probably needs to get less strong for the Fed to achieve its target of 2% inflation, a weakening of the job market concentrated primarily at relatively high-end white-collar employers might be the best plausible outcome.

Layoffs are always happening

Part of the misapprehension about these layoff headlines is that there’s a tendency to underrate the amount of overall churn that happens in a large and dynamic economy. When you read a story like “the U.S. economy added 250,000 jobs last month,” that’s a net figure of new jobs minus old jobs. Every month there are millions and millions of new jobs and also millions and millions of job losses.

To make a readable chart of net layoffs, you need to throw out two months of pandemic data, otherwise the y-axis gets so tall that any non-pandemic variation is hard to see.

One thing you see is that throughout the 21st century, there has never been a month that didn’t feature a million people losing their jobs. So while “nearly 1.5 million people lost their jobs last month, a pace of 50,000 per day” sounds incredibly alarming, it’s actually an unusually low number of layoffs.

Unfortunately, the most recent data is from November, so I can’t promise you the December layoffs were low. But the other thing that jumps out from this chart is that since the pandemic settled down, we’ve been in a two-year period of structurally low layoffs. So it’s not only that 12,000 people getting laid off from Google isn’t really that many people in the scheme of things, it’s that even if we really do so see a significant increase in the rate at which layoffs happen, that itself would just be a return to normal, not a sign of economic calamity.

If you look at the ratio of people who work in restaurants to people who work in the information (tech/media) sector, you’ll see that even at the depth of pandemic furloughs, food service was nearly 2.5 times bigger.

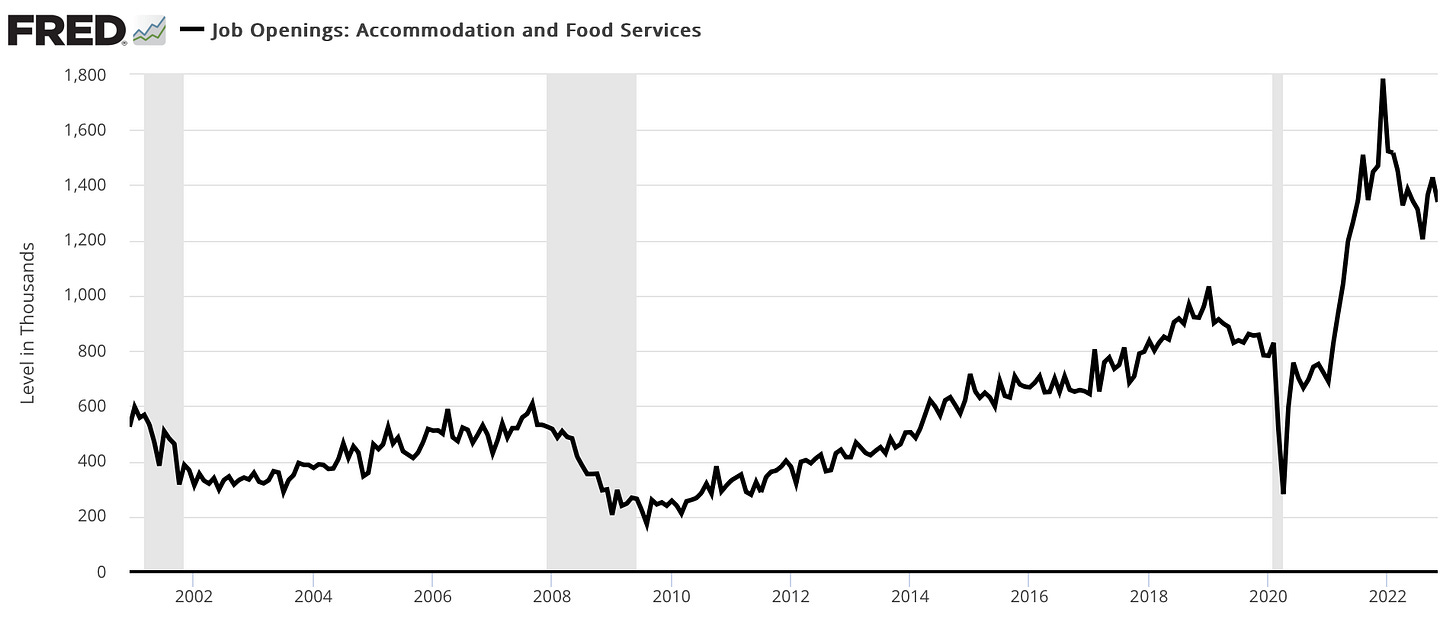

And on top of that, there are still plenty of positions available for anyone looking for work in this sector.

At the end of the day, that’s where the real heat in the labor market is coming from.

The very large, historically low-wage, and not-that-desirable food service and retail sectors are eager to hire more people. Eager enough that they’ve been raising wages rapidly enough to start shrinking income inequality — but not so rapidly as to change the fact that these are fairly low-wage, undesirable jobs that people move out of if they can.

Meanwhile, the tech companies doing widely covered layoffs are still employing more people than in the recent past.

Big tech super-sized at an incredible pace

Consider these stats:

Alphabet grew from 119,000 employees in 2019 to over 150,000 in 2021.

Microsoft went from 144,000 in 2019 to 181,000 in 2021 and then grew over 20% in 2022.

Salesforce went from 35,000 in 2019 to 74,000 by 2022.

Netflix went from 8,600 in 2019 to 11,300 in 2021.

Meta went from 45,000 in 2019 to 72,000 in 2021.

Layoffs are really shitty for the specific people who are losing their jobs. And in some cases, the people being laid off have been with these companies for a long time and feel a real and acute sense of betrayal.

But without minimizing what’s happening on a human level, zooming out it’s clear that tech went on a wild hiring binge that they’re now pulling back from. When companies try to hire and expand, not everyone who is offered a job works out and not every project is successful. But as long as the overall company is growing at a breakneck pace, you don’t necessarily have strong incentives to do rigorous look-backs at every hire.

Then the Fed raises interest rates in a way that specifically hurts the valuations of tech companies, and suddenly it’s time to re-evaluate.

So you get this wave of layoffs that’s driven by a mix of shifting macroeconomic circumstances and social contagion among CEOs. For a while, it was conventional wisdom in Silicon Valley that there was an all-out war for talent and you couldn’t hire too aggressively. Then vibes started to shift to the idea that big tech companies are all overstaffed, and when Elon Musk proved you could lay off tons of Twitter staffers without obviously breaking the site, cost-cutting became the new cool trend.

But the economy functioned fine back in 2019 when these companies were much smaller than they’d become by 2022. And even the most aggressive layoff rounds I’ve seen announced still leave big tech much larger than it was just a few years ago.

The upside of down

The computers-and-related-things industry has been very focused on seeking out opportunities for high margins in winner-take-all markets. But there are lots of markets that don’t have winner-take-all dynamics where it is still helpful to use computers and related skills. The problem is companies operating in normal competitive markets haven’t been able to compete on compensation for employees with high-end technical skills as long as big tech was expanding rapidly. But as Gabrielle Coppola writes for Bloomberg, now that big tech is contracting, lots of places would like to hire engineers:

While the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas is best known as an annual excuse to marvel at outlandish gadgets, Dirk Hilgenberg, head of Volkswagen AG’s software unit, came to this year’s show in early January looking for a different kind of tech product: software engineers.

The 58-year-old German auto executive turned his CES booth, a colorful stack of shipping containers, into a makeshift hiring hall with the words “JOIN US” emblazoned across the side. His unit, dubbed Cariad, has quintupled its headcount, to about 6,600, since its formation in July 2020, and Hilgenberg is hoping to hire an additional 1,700 people this year. To lure attractive candidates, he’s taken a liberal approach to remote work and made English Cariad’s de facto language—a concession for an automotive behemoth built on proud German engineering. Cariad’s goal, as he told a Bloomberg Businessweek reporter, is “tapping into the talent and experience pool of US companies.” He was using the show as a jumping-off point for his recruitment campaign. “The time couldn’t be any better,” he said.

The other possibility, of course, is startups.

Some people who lose their jobs will find themselves pushed to actually give that startup idea a try. For a larger number, though, they will become part of an available labor pool for startups to hire, a dynamic that will in turn make it easier for people who have startup ideas to get them off the ground.

One of many differences between working for a startup and working for a large established company is that at a startup, you’re going to get paid less. In exchange, you will get some probably-worthless stock options that may become extremely valuable in the future (but probably won’t). This is a really good tradeoff for a national economy that’s facing inflation, because it essentially forces people to reduce their present-day consumption in favor of future consumption that will occur when some minority of those stock options turn out to be valuable.

Of course any kind of layoff has that consumption-reducing effect. But it would be much worse to have inflation curbed by the poorest and most marginal workers losing their jobs and needing to cut their consumption. If well-compensated people end up doing it, though, that’s a model for egalitarian growth. A boom in startups and an expansion of technical talent outside the “tech” sector, meanwhile, would lay the foundations for a stronger economy over the long run.

Seeking labor market equilibrium

That said, just because it’s a “tech company” that’s doing layoffs doesn’t mean all the people losing their jobs are engineers.

Part of the difference between a startup and a giant established company is the giant established company adds lots and lots of other kinds of workers. There’s a lot of middle-management. There are big legal and PR departments. There are people who staff the offices — security guards and receptionists and people operating cafeterias. Big companies are just big, and they employ generic kinds of labor regardless of the specific corporate sector.

And here’s where it’s important to acknowledge that the overall job market remains robust.

Chipotle announced last week that they are planning to add 15,000 retail workers in advance of what they anticipate to be a seasonal rise in demand for burritos. And while Alphabet shedding a bunch of support staff probably won’t materially impact the output of Google web search or YouTube, the number of burritos that Chipotle can serve really is limited by the number of people that they can hire.

We’re no longer dealing with the depressed economy of the Obama era where every job was better for the national economy than the alternative of no job at all. What we have instead is still a very strong climate for getting a job, and tons of places across the service sector that are visibly understaffed.

Beyond fast food, an easier hiring climate could be especially good for the public sector. There are significant staffing shortages right now in police departments across the country, which tends to get politicized with a specific ideological valence. But you also see significant staffing shortages in public schools, which gets politicized with a totally different ideological valence. But there are also staffing shortages in the library sector and for water treatment plant operators. Teachers and cops just happen to be the most numerous, most high-profile, and most politically contentious class of public sector workers. The real issue is systematic, and it’s that when you get an inflationary labor market, it’s hard for government agencies to use signing bonuses and other private sector tactics to attract and retain labor.

A little bit of private sector cooldown is just what’s needed to make it easier to fill positions. That’s especially true if state and local governments can get smart and show some flexibility in terms of who they are willing to hire and recruit. Unfortunately, I can’t guarantee that the economy will be all flowers and sweets across the course of 2023. But there are basically three ways America’s episode of above-target inflation could conceivably end. One would be a loss of central bank credibility and upward spiraling of price increases. The second would be tightening the monetary noose enough to generate a real recession. And the third would be something like “large-scale layoffs in a few economic sectors that allow the other sectors to expand without big wage increases.” That last one is the good outcome, the soft landing, and that’s what these headlines are a sign of.

The ability to look at a singular data point (or small number of data points) -- particularly on topics with emotional or social ramifications -- and not lose sight of the bigger picture is one of Matt's best skills. It also drives some of his critics crazy.

i'm excited for burrito season