Palestinian right of return matters

A central issue in an intractable conflict

Jonathan Guyer, the Vox foreign policy writer, has forgotten more about the Middle East than I’ve ever known, so I found it surprising, and noteworthy, that his long Vox article over the weekend explaining “How the Arab world sees the Israel-Palestine conflict” does not include the phrase “right of return” or the word “refugees” or any explicit reference to this underlying issue.

Because it seems to me that whatever you personally think about this idea, it is absolutely central to how the Arab world and diaspora Jews and secular Israelis all view the conflict. Which in turn means that it’s central to the collapse of the Two-State Solution as a political construct and to the collapse of the peace camp in Israeli politics that might have been inclined make a deal that was favorable to Palestinian interests. There is, in fact, a whole school of thought associated with Bill Clinton and American negotiator Dennis Ross that holds the right of return almost single-handedly responsible for scuttling the Camp David talks and preventing the emergence of an independent Palestine. Of course, many other well-informed people deny that’s the case or believe it’s an oversimplification.1 But even if you think it is factually incorrect to say the resolution of this conflict hinges on the right of return, its centrality to so many of the narratives around this issue makes it an important concept to understand.

Guyer, in his article, does discuss “Palestinians who seek rights and freedoms.” He quotes Rami Khouri on Arab public opinion as saying that most people in the Arab world would favor diplomatic recognition of Israel, but “they will not do that until the Palestinians get their rights” and that “the popular sentiment across the whole region supporting Palestinian rights is very strong and very deep.” And he criticizes Biden for having “an approach to the region that does not take into account the mass, popular support for Palestinian rights.”

I completely agree with that analysis.

The various autocratic regimes in the Arab world clearly have some degree of interest in setting the Palestinian issue aside and engaging with Israel. But the mass public in those countries rejects that, and the fact that this approach is deeply unpopular is very relevant to understanding dynamics in the region. Changes in the global energy system probably mean that the United States has the luxury of caring less about this than we did 20 years ago. But for our own domestic political reasons we remain very involved in the Israeli-Palestinian issue, and so it’s important to understand the related domestic political issues in the Arab world. And that means engaging with the question of what rights we’re talking about, exactly.

The origin of the Palestinian refugees

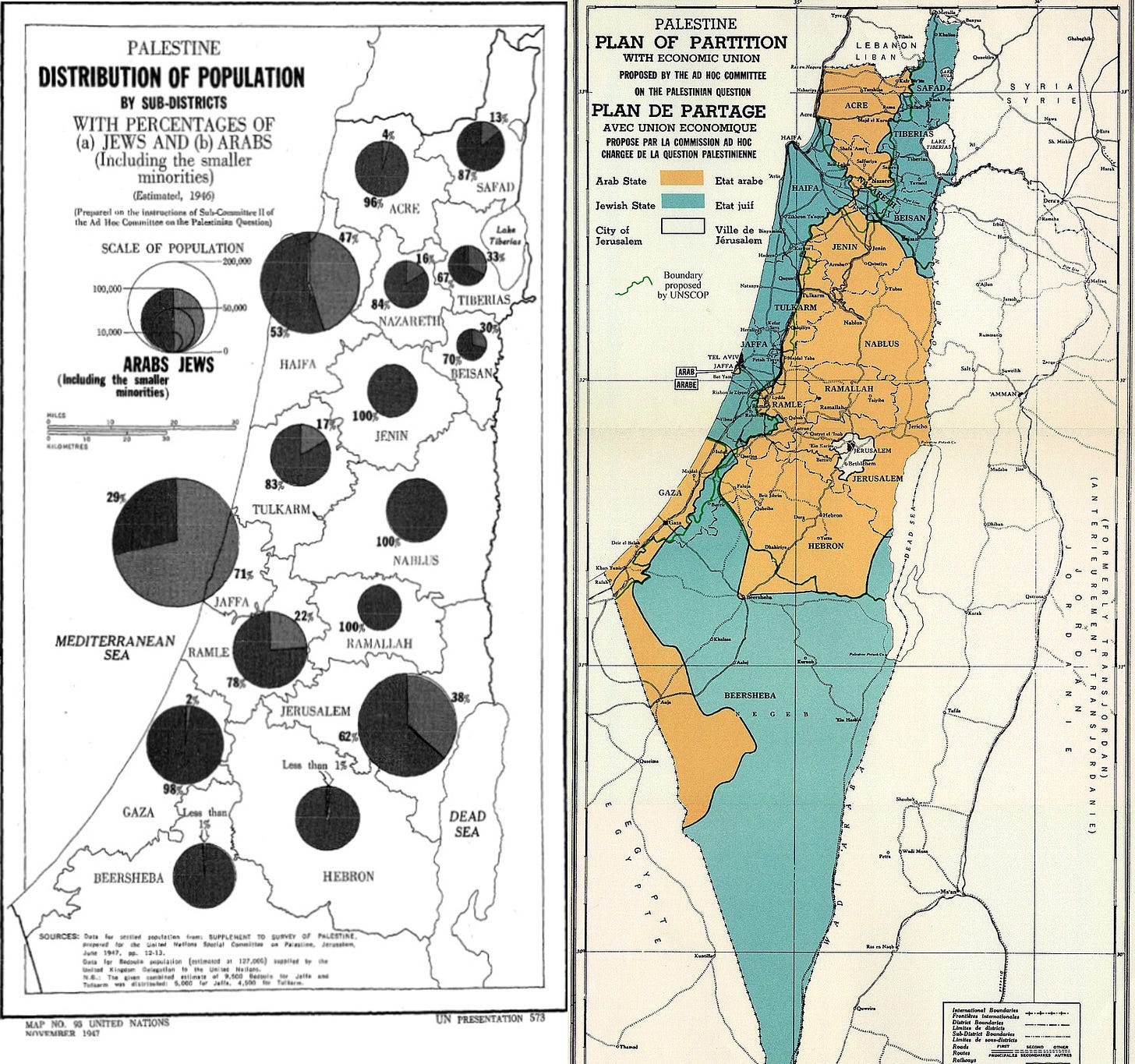

Israel was created by war in 1948 after the failure of a proposed partition plan that would have created two states, one with a narrow-ish Jewish majority and one with an overwhelming Arab majority. In the war that followed the collapse of this diplomatic plan, Israel controlled a land mass that was larger than what they’d been offered in the partition proposal. And despite the more expansive terrain, they ended up with a larger Jewish majority than was contemplated in the original partition proposal.

That was convenient, because in the context of pre-war Palestine, the advocates for the creation of a Jewish state faced a fundamental dilemma. On the one hand, they wanted their state to be larger rather than smaller. A larger state would have more physical security, a larger state would have more access to water and agricultural land, and a larger state would have access not only to the coastal plain around Tel Aviv and Haifa but also to Jerusalem and other sites of religious significance. On the other hand, they wanted their state to be a Jewish one, and the presence of a Palestinian majority would’ve rendered that impossible.

So what happened? Well, a lot of Palestinians who’d originally been living inside the territory that Jews won during the Israeli War of Independence left during and shortly after the fighting.

Specifying how and why, exactly, this leaving occurred is contentious. The standard Zionist position (the one I was taught in Hebrew school, for example) is that Palestinians voluntarily left their homes at the urging of the warring Arab states — primarily Jordan, Egypt, and Syria — with the promise that they would soon return as conquerors.

The standard Palestinian nationalist position is that they were ethnically cleansed at gunpoint.

This interpretive disagreement is an important point of contention when it comes to commemoration of the Nakba (or “catastrophe”), the Arab name for these events that Israel characterizes as a victorious war of independence. In pro-Israel circles, this terminology is understood to mean that Arabs believe Israel coming into existence was a catastrophe. In other circles, the term is understood to refer to the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians who previously lived inside Israel’s 1948-1967 borders.

I do not, personally, think that reconstructing strictly accurate accounts of events that occurred generations ago is generally all that helpful in solving present-day problems. I think Israelis could square the circle somewhat by accepting the Palestinian narrative about the origin of the refugee problem, but a version in which the “catastrophe” was the displacement of people rather than the creation of the Jewish State per se. In that view, Palestinians can mourn their Nakba (just as Israelis mourn the Holocaust and the expulsion of Middle Eastern Jews from their homes), while Israelis celebrate their independence. The harder question is what follows from this.

The right of return

The answer, in pro-Palestinian circles, is clear. Those who left and their descendants should return to the towns, cities, and villages where they lived before the Nakba. Here I’ll quote from Amnesty International:

“More than 70 years after the conflict that followed Israel’s creation, the Palestinian refugees who were forced out of their homes and dispossessed of their land as a result continue to face the devastating consequences,” said Philip Luther, Amnesty International’s Research and Advocacy Director for the Middle East and North Africa.

“This weekend almost 200 million people will tune in to watch the Eurovision song contest in Israel, but, behind the glitz and glamour, few will be thinking of Israel’s role in fuelling seven decades of misery for Palestinian refugees.

“There can be no lasting solution to the Palestinian refugee crisis until Israel respects Palestinian refugees’ right to return. In the meantime, Lebanese and Jordanian authorities must do everything in their power to minimize the suffering of Palestinian refugees by repealing discriminatory laws and removing obstacles blocking refugees’ access to employment and essential services.”

There are currently more than 5.2 million registered Palestinian refugees. The vast majority live in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT). Israel has failed to recognize their right under international law to return to homes where they or their families once lived in Israel or the OPT. At the same, they have never received compensation for the loss of their land and property.

Israel as a whole has a population of about 9.7 million people, of whom approximately 7.1 million are Jewish. An influx of 5.2 million Palestinian refugees would completely upend the demographic balance of the country.

The normal response in Zionist circles is that this proposal would mean the destruction of Israel, or its destruction as a Jewish state. You’re supposed to say that Palestinian insistence on this right shows that the whole idea of a Two-State Solution is based on a misunderstanding. Western liberals see the proposal as the idea of one state for Israelis and a second state for Palestinians, but the Palestinians see themselves as proposing one state for Palestinians and a second binational state.

Conversely, if you read Benjamin Wallace-Wells’ profile of Peter Beinart, you see that as Beinart’s views have shifted from standard Zionist to progressive critic to post-Zionist, a key difference is that he is now a supporter of a right of return. Because if you are going to insist on the return of potentially millions of Palestinians to Israel, that means you have faith in the possibility of peaceful coexistence in a binational state. And if you believe in peaceful coexistence in a binational state, then simply creating one binational state for the entire area solves a bunch of other logistical problems. You suddenly don’t need to talk about uprooting Israeli settlements, about how to connect the West Bank and Gaza, or about who has access to Jerusalem and other holy sites.

But if you forget everything you know about the conflict in the Middle East and just think about immigration politics here in the United States (or wherever you live), you can see that this is a big pill for the electorate to swallow. Forgetting the ideological structure of Zionism or the particular ethnic and religious animosities at issue here, people everywhere tend to be extremely skeptical of refugee inflows on that scale.

For the past 10 years, I have been attempting to achieve a more zen-like open-mindedness on questions of how things should be arranged in distant places that I have no personal connection to. But I do think that if you’re going to write articles about the central role of Palestinian rights in Arab politics, you need to be very clear what rights you’re talking about, because the question of how heavy a lift it is to get Palestinian rights respected hinges in part on what rights are being claimed.

The Palestinian cause or the Palestinian people

Zeroing-in on the refugee question is particularly important if we’re concerned about the state of Arab public opinion.

Guyer writes that “Palestine is so central to the Arab Middle East that even US military leaders historically understood the peril of ignoring the Palestinian cause.” And I think it’s important to understand what that turn of phrase means.

You might think it means Arab public opinion is extremely sympathetic to Palestinians and eager to see Arab governments help Palestinians have better lives. Were that true, you might expect to see Egypt opening its doors to refugees fleeing the carnage in Gaza. Of course that would be a logistical and economic burden on Egypt. But countries like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates are right there and could help out with money. You can, of course, understand from general immigration politics why Egypt might not want to do this and why the richer Arab states might not want to help out with money. Generally speaking, “you should do stuff to help foreigners” is a hard sell in politics.

What’s peculiar about the Palestinian issue, though, is that this normal level of indifference to the welfare of foreigners coexists with what we’re told is a profound level of preoccupation with their fate.

The key is that their concern is the success of the Palestinian Cause (the reversal of the Nakba) rather than the welfare of the Palestinian people.

Note that Amnesty sort of glossed over the fact that Palestinian refugees living in Jordan and Lebanon lack full access to employment rights and social services. And in this context, “Palestinian refugees” does not necessarily mean someone who fled from settler violence six weeks ago. If your great-grandparents were kicked out of their village near Acre when they were kids and fled to a refugee camp in Lebanon, and then had children in the 1950s, who had kids in the 1980s, who had you in the 2010s, then you are not a citizen of Lebanon. You are a stateless Palestinian refugee. And the Palestinian cause means fighting for your right to return to that village near Acre, not fighting for your right to enjoy citizenship in the country where you and your parents and your grandparents were born.

To be clear, this is a population of a few hundred thousand people out of millions of refugees, but the fact that pro-Palestinian advocacy generally does not mean advocating for the right of people born in Lebanon or Jordan to become citizens of those countries is relevant to understanding broader dynamics.

Egypt’s role in the Gaza crisis

If you imagine a generic situation where County A is waging war on Country B, displacing civilians and endangering their lives, you would expect many residents of Country B to attempt to flee to nearby Country C.

And in almost every case, this would be a controversial situation in Country C — large refugee influxes are always a big deal and often unwelcome. But one would also expect a fairly straightforward debate in which Country B’s supporters urge Country C to be more generous, and Country C’s refusal to let Country B’s residents in is seen as a sign of hostility. It’s important to recognize that, due to the politics of the right of return, this is not how Egypt’s refusal to allow civilians to flee Gaza is seen.

On the contrary, as Abdallah Fayyad, the Palestinian-American writer and son of former Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad explained last week, to be spending time and energy on pressuring Egypt in this regard is seen as a form of complicity with Israeli ethnic cleansing.

But you could construe basically any refugee situation in this way.

During the Syrian Civil War, you could’ve argued that urging European countries to accept Syrian refugees should be understood as a form of complicity with the Assad regime. Letting Ukrainian women and children flee the war zone for safety in NATO states could be construed as a form of complicity with Putin’s invasion and desire to Russify eastern Ukraine. The construction of narratives is a discursive process that can go in different directions. But whatever you think about the issue on the merits, it’s important to understand that this is the way the Palestinian cause has been constructed.

You can imagine a kind of guy who runs around advocating for the following ideas:

Egypt should open the borders with Gaza and allow unarmed people who can pass some kind of background check to leave the “open air prison” and enjoy life in a neighboring Arab state.

Lebanon, Jordan, and other countries should either grant birthright citizenship to the descendants of Palestinian refugees who live in their countries or, at a minimum, create an easy naturalization process.

The Gulf States, which currently rely heavily on foreign labor, should tilt away from their current reliance on workers from Africa and South Asia and give more visas to Palestinians.

You don’t actually need to imagine that guy, though, because I have met guys like that and they are either right-wing Israelis or Jewish Republicans here in the United States. Clearly Palestinians would be much better off, on average, if this agenda were implemented. But not only is this not a strategy of the Palestinian cause, advocating for it would be seen as incredibly hostile to the Palestinian cause.

In part that’s because it’s not what most Palestinian individuals and organizations want. But even that is a little bit too simplistic. Because the fear, of course, is that lots of Palestinians would welcome the opportunity to emigrate. Conditions in the West Bank and especially Gaza are awful and if other Arab states (or for that matter the United States) were more welcoming to Palestinian emigrants, lots of people might choose that option, just as over the years many people displaced by war or ethnic violence have made permanent homes for their families in new countries.

The politics of position-taking

I don’t have a stunning conclusion to offer other than “peace in the Middle East seems like a hard problem.”

But even though that conclusion sounds banal, I do think it’s important. As we started with Guyer and his article, it’s clearly true that “mass, popular support for Palestinian rights” is a very important feature of public opinion throughout the Arab and Islamic world, which in turn raises the question of what those rights are understood to be. As it happens, Palestinian rights are defined in this discourse in a way that Israelis understand as being incompatible with the fundamental existence of their country. That makes the problem much thornier than if it were just a dispute about the exact borders of a Palestinian state.

In the west, we frequently see a politics of pure position-taking around this.

You can become a good progressive ally by espousing certain slogans at the cost of alienating yourself from mainstream Jewish institutions or vice-versa. But none of that amounts to a practical strategy for resolving anything. All kinds of countries all over the world mount fierce resistance to the idea of dramatically revising their immigration policies to permit much larger uncontrolled inflows, over and above the specific historical factors at play. Of course if Israelis had totally different opinions from the opinions they actually hold, this might be a relatively easy problem to fix. And by the same token, if the nature of the Palestinian Cause were defined differently, then the problem of improving Palestinians’ lives and welfare would likely also be much easier to solve.

Given the actual configuration of views, though, it’s a very challenging situation. And if you don’t acknowledge how hard the underlying problem is, you’re likely to end up underrating the behavior of various third parties — like complaining that the Biden administration is just lazily failing to find a solution — when in fact it really just is a hard issue.

It turns out that the Israel-Palestine conflict is a contentious issue.

Egypt was spectacularly uninterested in taking Gaza back when they made peace with Israel. And that was before it was full of the Muslim Brotherhood. Jordan fought off a Palestinian coup against King Hussein in the 1970s and the PLO helped destabilize Lebanon in the 1980s prompting an Israeli invasion.

The idea that 5 million Palestinians could immigrate into Israel and coexist seems fantastical given historical Palestinian attitudes and the current attitudes that see Hamas with strong support. Are there any Palestinians with any kind of power that are actually interested in coexistence? And before we start talking about the Palestinian Authority, Abbas is an old man and the PA is famous for its corruption. Is it even going to survive Abbas's death?

It is very difficult for Israelis to accept a "right to return."

One thing that seems omitted from these discussions is how Arab countries expelled or compelled their Jewish populations to leave during the 20th Century. These states offer neither a "right to return" or political protection for Jewish persons who would chose to return.

The Palestinian population is generally hostile to an Israeli state and mass in-migration of said population into Israel creates a real physical security threat for those already living there. The Jewish population rightfully fears a repeat of Pogroms and their own expulsion.

Arab states refusing to give political rights or safe harbor to Palestinians is just part of the intransigence on the part of Muslim Arabs that makes the two state solution impossible. They rejected the 1947 two state solution from the UN while Israelis accepted it. This is because they believed they could claim everything and expel 1/3 of the population by force.

There just doesn't seem to be a credible negotiating partner on the Palestinian side. They do not give up irredentism. They do not promise peace. They start with "give us everything and you get nothing" as their bargain.