“National” conservatism is un-American

Liberals should respect our heritage; conservatives should see that our heritage is liberal

Many on the American left reacted to Donald Trump’s first term by getting really interested in things like racial resentment literature in political science, critical theory, and historiographical traditions that emphasize the brutality and ugliness of America’s past.

I, personally, got less interested in that stuff as a reaction to Trump.

I thought a lot about my grandfather, who was a communist and who also served in the Navy in World War II, fighting Nazis in the Mediterranean and up and down the Italian peninsula. Like a lot of little boys of my vintage, I was interested in grandpa’s war stories. But he was interested in political education and liked to talk not only about the war but also about the Spanish Republic and the significance of the fact that the American volunteer brigade that fought for it was the Abraham Lincoln Brigade with its two battalions named after Lincoln and George Washington. These entities adopted patriotic iconography in part for cynical marketing reasons but also in part to elucidate important strands in the American political tradition. Jose Yglesias was the precise opposite of an apologist for the worst moments in American history, but at least as I knew him, he was absolutely a patriotic American. He was proud of American principles and wore the uniform proudly to fight for a good cause.

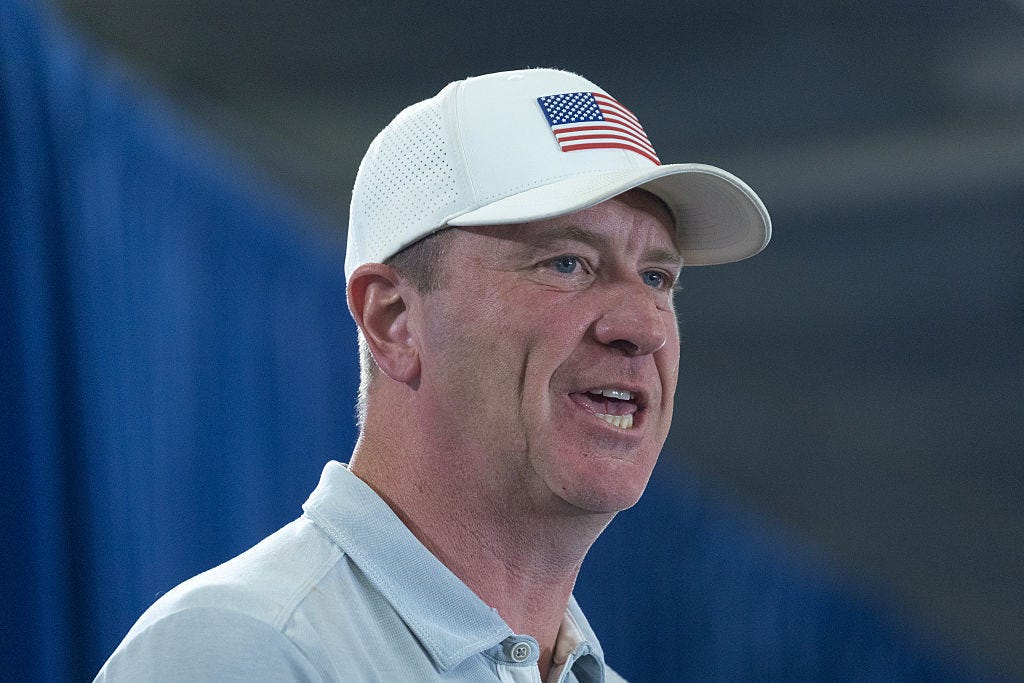

Republican Senator Eric Schmitt gave a speech at the National Conservatism Conference last week in which he not only criticized liberals but also the Reagan-Bush tradition of conservatives.

Many of his points certainly could have been made in a deflationary way. He criticized the design of the H-1B program, which he correctly noted does not actually select for the most-skilled workers in the way that a skilled visa program ought to. “There are flaws in the technical design of a visa program” strikes me as a reasonable point for a senator to raise, or even to write a bipartisan bill on — I would certainly cheer.

But what made the speech so provocative was his bitter, conspiratorial tone:

We have funneled in millions of foreign nationals to take the jobs, salaries, and futures that should belong to our own children — not because the foreign workers are smarter or more talented, but merely because they are cheaper and more compliant, and therefore preferable in the eyes of too many business elites who often see their own countrymen as an inconvenience.

Schmitt then turbocharged this zero-sum demagoguery into a wholesale rejection of the Enlightenment principles the country was founded on.

He denounced the notion that America is an idea. He quoted Bill Clinton’s line that “our America is not so much a place as a promise” and rejected it. He denounced talk of America as a universal nation. And he said that what’s great about Donald Trump is that “he knows that America is not just an abstract ‘proposition,’ but a nation and a people, with its own distinct history and heritage and interests.”

This generated tremendous backlash from liberals on the internet (and rightly so), with many scrambling to dig up their favorite quotes from Jefferson and Lincoln.

And I will say on Schmitt’s behalf that I agree with his analysis of what makes the MAGA movement so exceptional, which is not so much its specific points about immigration but its rejection of the universalistic American creed.

I agree with the liberals who reacted in horror to Schmitt’s worldview. But I would hope we can actually hang on to that moment of horror and encourage people on the progressive side to genuinely appreciate the nobility and lineage of the American liberal political tradition.

A new nation, conceived in liberty

Schmitt is correct that the United States of America is not just an abstract idea; it’s an idea that’s instantiated by specific people with a specific culture and legacy. I would also say that the idea itself also has a specific history. The American political tradition descends from the English political tradition and (according to Bernard Bailyn) specifically from various “Country Party” thinkers who, starting in the late 17th century, began articulating what would become the ideas of the Whig Party and later the English Liberal Party.

Another important aspect of this heritage is that many American colonies were founded largely as refugee sites for members of different dissenting churches — mostly Calvinists in New England but also Quakers in Pennsylvania and Catholics in Maryland — with an important (at least according to New Yorkers) dose of religious tolerance from the Dutch in New York.

Which is just to say that to the extent that “America is an idea,” it’s not an idea that the founding fathers made up at random.

We’re talking about people who are mostly of English ancestry, who are participating in the English cultural sphere and trying to articulate ideas that would make sense to English people. But when the conflict with the crown and Parliament escalated, and the founders clearly did feel that they needed to articulate ideas, I think it’s important to note that those ideas looked beyond the specifics of their experience, at least to an extent.

When the Slovaks broke off from the Czechs, they articulated an ethnic idea. They argued that even though Czech and Slovak are similar languages, the Slovak experience of Czechoslovakia had been one of being second-class citizens in their own country. Their official declaration of independence references “the thousand years’ struggle of [the] Slovak nation for independence.”

The American Declaration of Independence is not like that.

It does not argue for some ethnic distinction between Americans and English that needs to be respected. It argues that the English government has contravened Americans’ natural rights as human beings and that for this reason, Americans must create new political institutions that respect those rights. This is a specific text about specific people in a specific situation, but what those people chose to do in that situation was articulate a universal vision.

And this is what’s special about America. The American story is not just the story of a particular band of English people going to a new place, doing some conquering and expansion, and experiencing ethnogenesis as a result of distance. It’s a story of people who articulated a universalistic liberal vision of human rights and human equality, and while our heritage as a people absolutely matters, that universalistic vision is our heritage. That’s why Abraham Lincoln, when consecrating the battlefield at Gettysburg, not only said we are a new nation conceived in liberty but also referenced “our fathers.” He knows that many Americans do not, in fact, trace their literal ancestry back to the revolutionary era. In particular, in Lincoln’s time there were many relatively recent arrivals from Ireland and also Germans, like Schmitt’s ancestors, who came here after the failure of the Revolutions of 1848. But the way the founding-fathers metaphor works is that we are all Americans, and they are the fathers of the country, and thus “our” fathers.

This is obviously no more literally accurate than the idea that Slovak ethnic identity existed hundreds of years ago. But nations are imagined communities built around various conceits, and this is our conceit.

An Empire of Liberty

The original United States of America was small and surrounded by the colonial possessions of various European powers. But Thomas Jefferson bought the Louisiana territory from France in 1803. He wrote in 1809 to James Madison that he’d like to see the United States annex Cuba and also take over Canada and eventually, “have such an empire for liberty as she has never surveyed since the creation.”

Jefferson posed the question of whether there is any limit to the future territorial expansion of the Empire of Liberty, and came up with the limiting principle that “nothing should ever be accepted which would require a navy to defend it.” Jefferson was suspicious of the idea of a large standing military force, so to him, the relevant consideration was that Cuba was close enough that the country wouldn’t need a big navy.

That’s all a little strange, but versions of Jefferson’s thinking remain foundational to the nature of the country. The Constitution envisioned from the beginning that new states would be added to the original thirteen and that all states would exist on an equal basis. Jefferson’s Northwest Ordinance made this a practical reality and set the process of creating new states in motion. The Louisiana Purchase established the precedent that not only was the country not limited to the original thirteen colonies, it also wasn’t limited to the lands ceded in the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

This idea of new states on equal footing with the old ones was non-obvious and at odds with most of the historical experience of republican government.

But it’s fundamental to the idea of America, which isn’t just an idea but is definitely an idea.

So many aspects of American life and American history don’t make sense unless you can see that. Not just the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address but things like the widespread celebration of the American flag, which is an effort to make an abstraction concrete. And when you pledge allegiance to the flag, you also pledge allegiance to the republic for which it stands — a specific constitutional order, not a specific ethnic group — and repeat the specific propositional content of “with liberty and justice for all.” That’s an idea. That’s the unifying concept that justified political separation from England and that underwrote cooperation between groups of people who at the time were seen as having profound religious differences of the sort that might make political coexistence impossible.

Schmitt attacks a straw man, saying, “If you imposed a carbon copy of the U.S. Constitution on Kazakhstan tomorrow, Kazakhstan wouldn’t magically become America. Because Kazakhstan isn’t filled with Americans. It’s filled with Kazakhstanis!”

Okay, sure. But even though the idea of liberal constitutional government has a kind of specific Anglo-American Protestant origin story, we have, in fact, seen it spread to Japan and Botswana and elsewhere. It doesn’t make sense conceptually to imagine Kazakhstan embracing Hindutva or Zionism, because those are particularist ethnic ideologies that would cause Kazakhstan not to be Kazakhstan. The point of liberalism isn’t that Kazakhstan becoming liberal would make it America; it’s that the idea of a liberal Kazakhstan is perfectly coherent but the idea of an illiberal America is not. We are conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Conversely, if a Kazakh moves to America and works hard and plays by the rules and embraces American values and raises a family here, then that person is an American.

To secure for our posterity

Ronald Reagan said this brilliantly in his final speech as president: “You can go to live in Germany or Turkey or Japan, but you cannot become a German, a Turk, or a Japanese. But anyone, from any corner of the Earth, can come to live in America and become an American.”

This is not a call for open borders, or a statement that everyone from every corner of the Earth should come to America simultaneously, or even an assertion that anyone who shows up here will magically become American.

It’s a claim about the nature of the American idea and the meaning of the American polity. You can tell that, on some level, Schmitt lacks the courage of his convictions and picked for his example a country — Kazakhstan — from which almost no Americans have ancestry. It would have been spicier, more provocative, and more honest to denote a specific immigrant community that does exist in the United States in substantial numbers that he views as inherently un-American and explain why. Is he taking about Venezuelans and Salvadorans? Cubans? Mexicans? Black people? Muslims? Indians? Who? Picking on Kazakhs offers the frisson of racialist politics without having to look anyone in the eye and really say what you mean.

And there was a time, of course, when people were saying exactly this about Schmitt’s great-great-great-grandparents and other Germans.

A much more restrained claim would be that for all the universalism of the American political tradition, the Constitution does say that the point is “to secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.”

The principles are universal, but the scope is limited. Americans acknowledge the humanity and moral worth of all people, but as a joint political project, our constitutional government has a particular obligation to American citizens. This point was part of my common sense manifesto, and I think reluctance to say it clearly fuels illiberal politics. The Biden administration acted for years like a deer stuck in the headlights with asylum claims, unwilling to say it welcomed large numbers of new arrivals and painfully aware that the public did not want to, but still tied to the post that the sanctity of the asylum process had to be protected over all else. When they finally acted, though, it worked pretty well and could have put immigration policy on a sustainable basis without “mass deportation” had Harris won the election.

Most Democrats sincerely and correctly believe that immigration is generally beneficial to the United States. The way to fight on this topic is to genuinely commit ourselves to the America First framing of what immigration is for, and to take seriously our obligation to make choices around the margin to maximize the benefits of immigration to Americans. That gives us the opportunity to expose the MAGA stance for what it is — not a defense of American interests but a betrayal of American values in favor of a weird quasi-European form of ethnic nationalism that’s at odds with America’s authentic tradition as the quintessential liberal country.

You can drop the mic, Mr. Yglesias, for this cannot be improved.

Matt's excellent piece here reminded me of an old Irish adage:

"A patriot is someone who loves his country; a nationalist is somebody who hates everyone else."