Liberalism and public order

Maintaining functional public systems and spaces *is* progressive

I put economics first on my manifesto, because it’s substantively the most important point. But item number two about public order is, I think, the most important politically.

Somewhere on the road from Barack Obama and John Kerry getting endorsed by national police unions in 2004 and 2008 to the present day, the Democratic Party has become ambivalent about the idea of punishing people who break the rules, to the point that the party says we need to accept disorderly and dysfunctional public spaces.

The starting point of that process is totally sensible: Democrats are the party of people with humane instincts, and there was a lot of interest in trying to find ways to make the American criminal justice system less cruel. That’s a reasonable and important problem to work on, and it’s something I’ve written about over the years (most recently in May). But it turns out, like many policy problems, somewhat difficult. And in too many cases, the fallback option has become just not enforcing the rules.

This is not politically viable. But it’s also worth saying that while humane impulses are good, letting public spaces go off the rails is a kind of false humanitarianism. Most low-income people are not criminals, and it’s precisely the poorest and most vulnerable people who most need things like public spaces and public transit and affordable housing and libraries, and they need these things to be actually good.

Hence, item two on the manifesto:

The government should prioritize maintaining functional public systems and spaces over tolerating anti-social behavior.

The point here, again, is not to deride humane impulses, but to insist that Democrats think rigorously about them. For years, I’ve read constant concern that as the Democratic Party voting base becomes more affluent, it will abandon aspirations toward redistributive politics. I think that mostly hasn’t happened, and Democrats are still very clearly the party that favors taxing the rich and providing things like Medicaid and a Child Tax Credit to low-income families.

But I do think it’s true that if you’re an affluent suburbanite, you can become psychologically detached from the problems facing lower-income people in more diverse neighborhoods, and excessively reliant on anti-growth exclusionary zoning as your de facto guarantee of public safety. That’s not kind or humane, it’s an abdication of responsibility to immigrants, to poor kids, and to everyone who deserves safe streets and pleasant, functional public spaces.

Defaulting to disorder is bad

I think this problem is summed up well in a series of tweets from Chris Hayes in February 2022 — after the backlash to “defund the police” and after the big rise in homicides that took place in 2020 and 2021 — in which he acknowledged that he didn’t have a good non-carceral solution to the problem of people breaking the rules and smoking on the subway, and said that in the absence of such a solution, his preference is to just let people smoke.

I bring this up because Hayes is admirably precise and because the disagreement I have with him on this is nuanced, but important.

I also do not want to see large numbers of police officers arresting people for smoking on the subway. But, like Hayes, I support the rule that prohibits smoking on the subway. And having a rule means that sometimes, someone needs to enforce it.

If we think about why nobody is lighting up in the restaurants these days, it’s clearly not the case that cops are posted up in every restaurant, making smoking arrests. If you lit a cigarette in a restaurant, the other patrons would say something. You’d be asked to leave by the staff. It’s possible that you would refuse, in which case the police would be called, and they’d probably be annoyed by needing to spend their time dragging a smoker out of a restaurant. But they would do it. It’s also, of course, possible that someone would react to being asked to leave by lashing out in a violent manner. One can only hope that if that happened, patrons and staffers would work together to restrain this person and minimize anyone’s odds of being hurt. And if someone responded to being asked to leave the restaurant by committing a violent assault, they would definitely be arrested.

Note that, in practice, the rules prohibiting smoking in restaurants do not generate large numbers of arrests. Anti-smoking laws are not a major driver of mass incarceration. What happens is that people mostly follow the rules!

From smart on crime to soft on crime

I have always been a big fan of the work of the late Mark Kleiman, and I really enjoyed his 2009 book, “When Brute Force Fails: How to Have Less Crime and Less Punishment.”

The theme of this book is that while locking up people who commit crimes for very long prison sentences reduces crime via “incapacitation” (you’re not carjacking anyone if you’re in prison), this approach is costly. The United States, even at its crime low point, has always been a violent society with an unusually low life expectancy for such a rich country, so finding new strategies for fighting crime — particularly ones that are less costly than ever-longer prison sentences —seems like a good idea. And one of these strategies is to consider what might happen if someone who would spend 15 years in prison under the current system instead did 10 years, and was then released under intrusive monitoring conditions (frequent drug and alcohol tests, 24/7 ankle monitoring, not allowed to handle cash, etc). If they violate any of these conditions, they’re back in prison. If they make it a year, monitoring is cut back to just the ankle monitor.

This kind of surveillance should pack a lot of deterrent punch, and even though it’s expensive, it’s cheaper than incarcerating someone. That’s especially true when you consider the economic cost of keeping prisoners out of the labor force. Aggregate this shift across a thousand prisoners, and you’re saving enough money to hire more cops. Cops on the beat deter crime (economist Alex Tabarrok has been arguing for years that America has too many prison guards and not enough cops), so fewer people commit crimes and get arrested — less crime, less punishment.

Around the time that Kleiman’s book came out, San Francisco District Attorney Kamala Harris published her book, “Smart on Crime,” which featured Kleiman-esque themes around investing in prevention and rehabilitation. Both of these books were, I think, helpful contributions to a constructive conversation that Democrats were having about crime. In the 2012 platform, Democrats took tough on crime stances like, “Democrats are fighting for new funding that will help keep cops on the street and support our police, firefighters, and emergency medical technicians. Republicans and Mitt Romney have opposed and even ridiculed these proposals, but we believe we should support our first responders.”

They also nodded toward civil rights concerns and “smart on crime” considerations:

We will end the dangerous cycle of violence, especially youth violence, by continuing to invest in proven community-based law enforcement programs such as the Community Oriented Policing Services program. We will reduce recidivism in our neighborhoods. We created the Federal Interagency Reentry Council in 2011, but there's more to be done. We support local prison-to-work programs and other initiatives to reduce recidivism, making citizens safer and saving the taxpayers money. We understand the disproportionate effects of crime, violence, and incarceration on communities of color and are committed to working with those communities to find solutions.

We will continue to fight inequalities in our criminal justice system. We believe that the death penalty must not be arbitrary. DNA testing should be used in all appropriate circumstances, defendants should have effective assistance of counsel, and the administration of justice should be fair and impartial. That's why we enacted the Fair Sentencing Act, reducing racial disparities in sentencing for drug crimes. That's why President Obama appointed two distinguished jurists to the Supreme Court: Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor. Moving forward, we will continue to nominate and confirm judges who are men and women of unquestionable talent and character and will always demonstrate their faithfulness to our law and our Constitution and bring with them a sense of how American society works and how the American people live.

But by the time the 2016 platform was released, the conversation had taken a dramatic turn. In 2016, “Democrats are committed to reforming our criminal justice system and ending mass incarceration.”

What’s more, this iteration of the platform didn’t promise to be smart on crime in that Kleiman sense of finding cost-effective alternatives to incarcerations. What it says is that, “instead of investing in more jails and incarceration, we need to invest more in jobs and education, and end the school-to-prison pipeline.”

Jobs and education are great. But people don’t smoke on the subway because they don’t have a job. No one commits sexual assault because they didn’t learn algebra. And the call to end the “school to prison pipeline” just meant that in-school discipline should be more lax, which makes the educational experience worse for most kids. This kind of thinking reached its apogee with the surge of police abolitionism that swept many progressive groups in 2020. Thankfully, Joe Biden and other leading Democrats did not embrace defunding the police. But it is true that the 2020 platform, adopted at a time when shootings were visibly surging, doesn’t really say anything about reducing crime. And like the 2016 platform, instead of urging us to think intelligently about different modes of law enforcement, it frames the issue as a stark tradeoff between punishing crime and providing social services:

Instead of making evidence-based investments in education, jobs, health care, and housing that are proven to keep communities safe and prevent crime from occurring in the first place, our system has criminalized poverty, overpoliced and underserved Black and Latino communities, and cut public services.

There is absolutely evidence that certain kinds of social services — especially mental health and addiction services provided by Medicaid — can reduce crime. But unless you want to end up like Hayes, paralyzed when faced with blatant misconduct, you just have to admit that sometimes people do need to be stopped by the cops. Maybe treatment rather than prison is the right destination for many of those people, but what if they refuse treatment? What if they won’t comply with a job training program? You need some form of punishment to make these systems work.

A crisis of disorder

The good news is that after spiking for two years, murder started to fall in 2022 and continued falling in 2023 and 2024. Notwithstanding Trump’s propaganda, it’s just not true that the Biden administration was a period of soaring, out of control crime.

What is true, though, is that a lot of lower-level disorder that spiked alongside shootings in 2020 never went back to normal. Unruly passenger incidents are falling but still running way ahead of their pre-pandemic level.

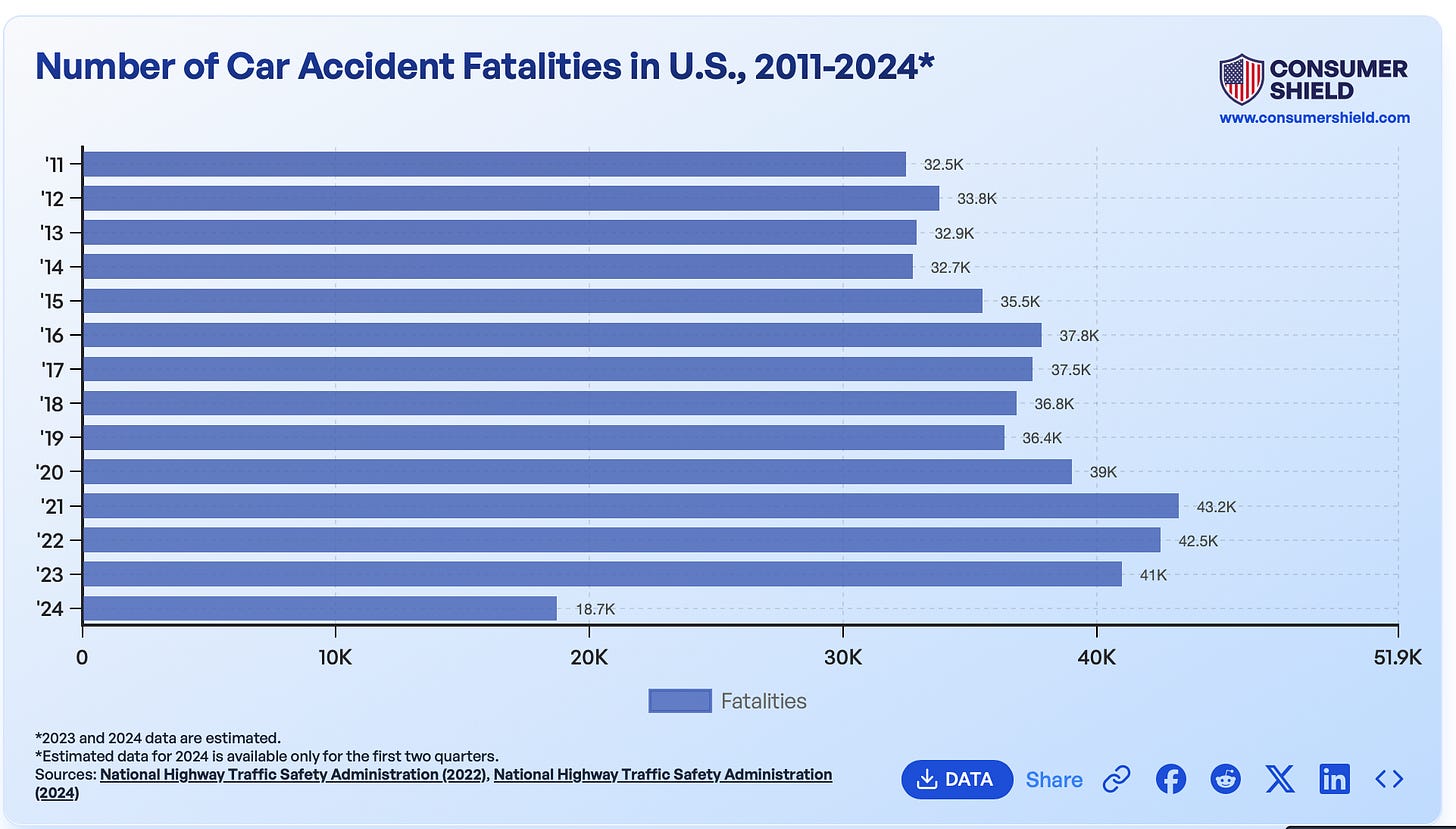

We don’t know where the full 2024 data will land, but at least through 2023, we had persistently higher rates of car fatalities due to a mix of reckless driving and increasing levels of DUI.

The question of to what extent shoplifting has actually increased in sharply contested, but at a minimum, retail stores have clearly felt compelled to lock up much more of their merchandise as an anti-shoplifting countermeasure.

Unlike in some areas where I think the Biden administration made clear policy errors, I don’t know that they did anything wrong about this national epidemic of low-level disorder. But for whatever reason, they weren’t willing or able to articulate the basic fact, visible to everyone, that standards of conduct had slipped and that something needed to be done. Why Biden was passive in the face of something that was possible to punt on is highly overdetermined, but an important part of the background is that by the 2020s, influential progressive figures really were articulating the view that it’s per se bad to use the police to stop low-level misconduct, even in cases when you concede that you don’t have a better idea.

Safety first

The question of exactly what you should do to control crime and disorder in a cost-effective and humane way is complicated.

But I really do think everything needs to follow from a basic statement of values. It’s not progressive to allow public spaces to become chaotic and unusable, and it’s profoundly not progressive to rely on exclusionary zoning as the main tool of public safety. Democrats shouldn’t accept racial profiling or “statistical discrimination” as a law enforcement tool or make apologies for clear cases of police misconduct. And they should also acknowledge that policing is a difficult, important job and that doing it properly requires officers to be proactive and to take risks with their personal safety. There are a lot of issues and difficulties downstream of urban police officers being so uniformly right-wing, but part of the solution to that is to urge more young liberals to consider law enforcement careers.

We also need to much more sharply distinguish between the idea of asking whether certain punishments are unnecessarily harsh, and trying to reduce mass incarceration by making it harder to solve crimes. Tools like surveillance cameras, DNA evidence, and facial recognition software that make it less likely people will get away with crimes reduce the amount of crime that happens, which ultimately is the sustainable route to less incarceration.

Public order is important — toothpaste shouldn’t need to be locked up, no one should be smoking on the subway, parks and buses and libraries should be nice places. And I don’t want incarceration to be the only solution to these problems or for anyone who breaks a rule to end up in prison. But building a more humane system has to mean actually finding better ideas for maintaining public order, not giving up on the goal.

“ Most low-income people are not criminals, and it’s precisely the poorest and most vulnerable people who most need things like public spaces and public transit and affordable housing and libraries, and they need these things to be actually good.”

Yup. Our public library was a very good institution even ten years ago. Now it has become an informal homeless shelter. And a place where drug-users shoot up — there have been a number of overdoses in the library.

This is not a good outcome for any progressive values or any progressive constituencies. It’s a catastrophe for all of the things and people we care about. Not to mention that it is hell for the librarians themselves.

Speaking bluntly: Chris Hayes sounds like a complete wuss in that thread.

Every law is ultimately enforced by a man (or woman) with a gun and the threat of incarceration. Every single law, whether that be speeding, tax evasion or arson. If you don't want to use those to enforce a law, then you are really saying you don't want that law at all.