Liberalism and globalization

Good economics, questionable political analysis

My basic thesis in this ongoing series about liberalism (see part one on what I mean by that word, and part two on the bogus argument that liberalism fails to provide meaning in people’s lives) is that American liberalism has entered a period of decline for mostly bad reasons and deserves to make a comeback. Here in part three, though, I want to give the critics their due for the thing that I think they are most correct about.

Liberalism is facing a moment of crisis in the United States and around the world.

One theory of the crisis suggests that it’s due to massive substantive failures. I think that this is mostly backwards and that some contingent electoral successes by illiberal figures like Donald Trump created a crisis of self-confidence that has undermined liberalism above and beyond anything Trump has done.

But I do want to concede some ground to critics of liberalism.

Any ideology is both a set of ideas and a set of actual human beings acting in the world. And I do think that specific politicians who rightly considered themselves to be operating in the liberal tradition made a few serious mistakes in the 21st century.

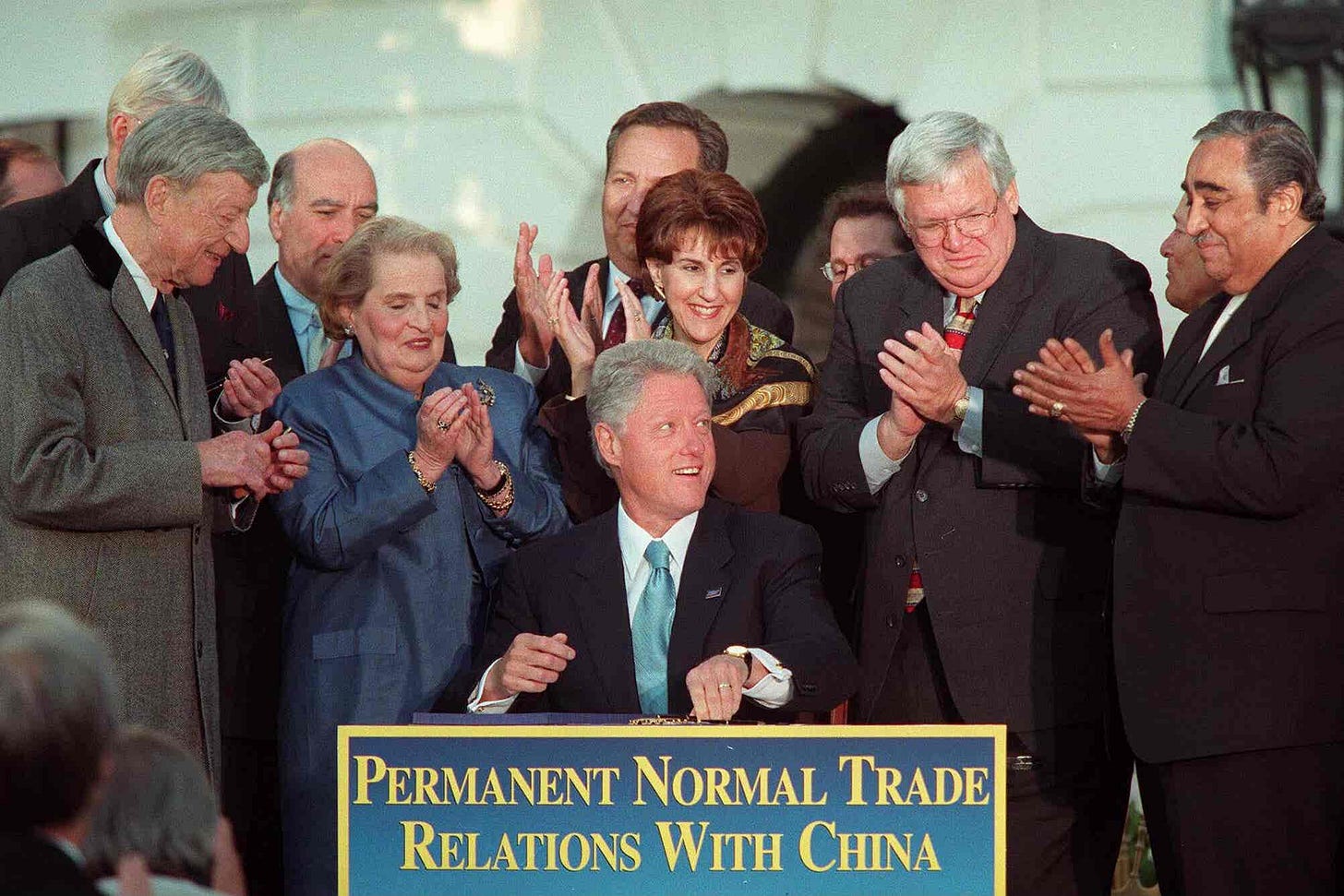

These mistakes related primarily to “globalization,” which has two parts, trade and immigration. This is terrain where liberal theory has always provided relatively minimal guidance, making it difficult to reach consensus on what — if anything — liberalism has to say. As a result, I don’t think that conceding (for example) that liberals were much too optimistic about the political trajectory of China requires us to give up on liberalism as such. If you go back and read F.A. Hayek or Mary Wollstonecraft or John Stuart Mill, those classic texts aren’t going to tell you what to think about Chinese political development.

Similarly, on immigration, liberal thought was roiled by internal disputes in the late 20th century.

Rawls wrote in his 1999 book “The Law of Peoples” that countries have a right to restrict immigration “to protect a people’s political culture and its constitutional principles” and argued that immigration limits are necessary to prevent a “tragedy of the commons.” That same year Susan Moller Okin wrote a book criticizing multiculturalism on liberal feminist grounds. These were very controversial arguments. Lots of thinkers, mostly younger ones, disputed the conclusions and argued that liberal principles commit liberal polities to a more cosmopolitan view than Rawls was allowing.

I have somewhat mixed feelings about these arguments. But the fact that they took place is a reminder that a range of different views on immigration are plausibly liberal. It should be possible to give voters who have concerns about immigration what they want without abandoning liberalism. Liberals cannot, in good conscience, adopt the kind of zero-sum economics that often goes along with skepticism of free trade or immigration. But concerns about national security or crime are not illiberal, and it’s the responsibility of liberal policymakers and practical politicians to do a better job of addressing these issues to maintain the faith of the public.

Chinese democracy

Let’s start with the trade side of globalization.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.