"Latinx" is a symptom, not the problem

You need to pay attention to what people actually think and want

Latinx Discourse is back in the news this week after the publication of an Atlantic article about how Hispanic members of Congress don’t like the word followed by a Politico story highlighting polling that shows “Latinx” is very unpopular with Americans of Latin American ancestry.

Personally, this is not my favorite “Democrats are doing it wrong” conversation for a few reasons. For one, like the defund-the-police conversation, it reeks of fighting the last war, arguing about tactical missteps during the 2020 campaign that don’t have that much to do with present-day problems for Joe Biden and congressional Democrats. It’s also (unlike the defund the police conversation) not an area where I think the left-wing activists are doing anything especially objectionable on substance. It is bad and counterproductive to use a group label that members of the group dislike, but there’s nothing sacrosanct about grammatical gender, and in plenty of contexts I support and encourage moves toward more gender-neutral language.

But most of all, I worry that what should be an entry point into a larger conversation about how the Democratic Party engages with Latino people will instead become a tedious dead-end, with half the people saying this word is dumb and the other half saying that there’s no evidence that this word, per se, is moving voters.

So here is my bottom line. I think progressives are sincere when they say they want to fight for the interests of America’s multiracial working-class and in favor of a stable multiracial democracy with political equality for everyone. But it’s essential to pay attention to what the people you’re trying to incorporate into your coalition actually think.

What are we even talking about here?

It’s worth drawing a distinction between how an individual chooses to identify and how an institutional or political actor should choose to address a group in mass communication. Every single ethnicity features internal diversity and some disagreement about preferred forms of address, and there’s nothing wrong with taking up a minority viewpoint as to how you identify. And in particular, if feminists don’t like the way Romance languages use male forms as generics or if people who are non-binary or gender-fluid resent the whole concept of grammatical gender, I can’t blame them. I am a native English speaker; we do not use grammatical gender in our language and know that plenty of other languages get along without it, too. I try in my personal practice to use non-gendered terms (chair instead of chairman, member of Congress instead of congressman) rather than male generics.

My personal advice to people writing or speaking in English who don’t like “Latino” would be to stick with “Hispanic” or use “Latin” as my grandpa Jose always did.

But of course this fight is also playing out in the native tongues of people who speak Spanish and other gendered languages. The history of the Indo-European languages is that over time, gender systems tend to get simplified. Latin’s three-gender system has given way to the two-gender systems of contemporary Romance languages. English went from three genders to two and now none. Afrikaans underwent a similar trajectory as it descended from Dutch. This is going to be a very contentious fight in countries where most people are accustomed to gendered language, but I’d bet that 100 years from now, grammatical gender is perceived as old-fashioned among speakers of Spanish.

The fact, though, is that people doing mass politics in the present need to try to speak the way that most people in the intended audience speak. And if they have to make a choice at the margin, the smart play is to talk the way the more politically moderate members of the community speak. And that means elected officials, as well as institutions like the DNC and policy and advocacy organizations operating in mainstream politics, should take the lead from Hispanic elected officials and eschew a term their constituents mostly dislike.

A symptom, not a cause

That being said, I do want to align myself with what Rep. Ruben Gallego has said about this, namely that it’s unlikely huge numbers of people are switching their votes based on choices of terminology. The issue is that if you’ve got a group of people talking this way, it likely reflects a lack of direct engagement with the community in question, which is going to be a larger political problem.

I think causes and symptoms get kind of messed up, and it can be useful to think about this outside the specific context of the debate around “Latinx.”

Occasionally I hear someone talking about “the Jews” rather than “Jews” or “Jewish people.” Nine times out of 10 this is just a person who’s on the older side and lives somewhere where there isn’t a significant Jewish community, so they are simply unaware that this is a disfavored way of talking, and I don’t hold it against them. But if the person doing this was putting themselves forward as a political custodian of Jewish interests, the fact that they are so out of touch with contemporary usage would raise an eyebrow or two. Voters don’t do an extensive audit of everyone they are making decisions on, so superficial cues can matter, especially if the cue signals “this person is not used to speaking to people like me.”

I use a Jewish example because that’s the primary cultural tradition I was raised in. Three of my four grandparents were Ashkenazi Jews, and I grew up in New York City where there is obviously a very large and active Jewish community.

But my other grandfather is an official Pioneer of Modern U.S. Hispanic Literature according to Arte Publico Press, and what that side of my ancestry wants to say is that there’s something kind of offensive about this even being a debate. Progressives normally distinguish themselves as being more fired-up about linguistic politics than moderate or conservative people and more insistent on deferring to the self-ascriptions of minority groups. The idea that we should make an exception to this for older, working-class, politically moderate people of Latin American ancestry who don’t favor the cancellation of the entire grammatical structure of Romance languages gets on my nerves.

And I think it speaks to a larger ideological issue, which is that progressives have been banking on the growing Hispanic population to create their hoped-for majority, but they seem very uninterested in paying attention to the actual views of Americans of Latin ancestry.

You need to pay attention to what people think

The most obvious and egregious example of this is the basic reality that the post-2016 fad for describing New Deal liberal ideas like Medicare for All as “socialism” is very politically harmful among immigrant communities with origins in Cuba and South America (and probably Vietnam, too, but that’s a different story).

This seems to be almost universally acknowledged to the point where, in some efforts to do early warnings about Democrats’ slippage with Hispanic voters in the 2020 cycle, there was a bit of an attitude that it doesn’t count if it’s limited to Florida. But of course Florida does count. Especially if progressives want to articulate a theory of politics in which they represent America’s future as a multiracial democracy against the forces of reactionary white nationalism, you can’t just write off Florida. If Florida was following the blueing trend of diverse, highly urbanized states like Georgia and Arizona, the whole national political scene would be pretty different.

But it’s not just Florida. Biden won Nevada in 2020, but it went from being a bluer-than-average state to a redder-than-average one. And while both Arizona (which he won) and Texas (which he lost) shifted blue, the Mexican American neighborhoods went in the other direction.

To the extent that this has been discussed in Democratic Party circles, it’s largely through the lenses of the need for investment and the problem of misinformation. These are both real things. Obviously, it is hard to win votes without investments, including investments in countering misinformation. But the flip side of that is investment won’t do you much good unless specialists in Hispanic politics convey information about Hispanic public opinion up the chain and are actually listened to. As one example, Gallup finds Hispanics have a relatively high level of confidence in the U.S. criminal justice system.

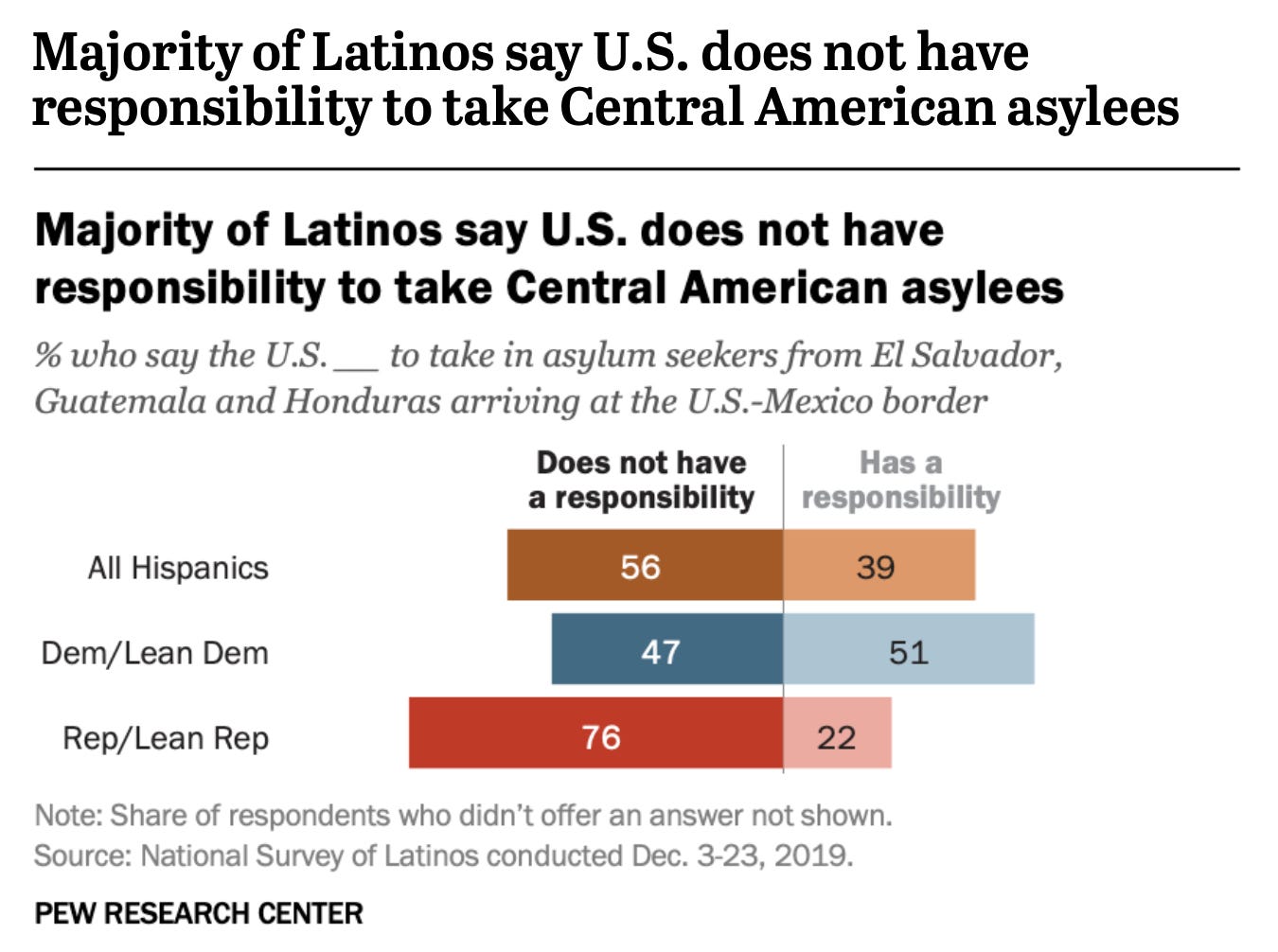

Another big one that I think reflects a real failure to pay attention to what people are actually saying is that while a path to citizenship for the long-settled undocumented population polls well with Hispanic voters, there is not a lot of enthusiasm for welcoming asylum-seekers from Central America.

I do not have access to a detailed breakdown of views on this by specific nation of origin, but I assume the basic story here is that Mexican Americans are very sympathetic to undocumented residents (who they perceive to be largely Mexican American) but less sympathetic to new arrivals from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador.

A different Pew poll from 2018 showed that compared to the U.S. population average, Hispanics were more likely to endorse the view that most people can get ahead with hard work, more likely to say their living standard is better than their parents’ was at the same age, and more likely to express optimism about their kids’ standard of living.

I don’t think any of that is particularly shocking; these are all ideas that have pretty clear roots in the immigrant experience. People move here because they perceive the United States to be a land of opportunity, and most immigrant families experience strong upward mobility for the first two or three generations. Just as with poor white people, if you want people’s votes, you need to pander to some extent to what they think.

The good news, though, is that Hispanic voters have plenty of progressive views.

Latinos favor big government (within reason)

Hispanic voters are more supportive than white Anglos of single-payer health care. They express strong support for a higher minimum wage and for the idea that the government should do more to solve problems.

The way I put this after the 2012 election when Obama cleaned up with Latinos is that the Hispanic electorate often behaves the way progressives wish white working-class voters would — voting in their economic self-interest and tuning out GOP culture war politics. But at that time, I think it was fairly accurate to characterize the dialogue as progressives driving a kitchen table message while Republicans did a lot of dog-whistling. By 2020, progressives had developed a split personality where Democrats’ overt campaign messaging in paid media continued to adhere to the pocketbook focus, but the broader progressive message in earned media came to be much more focused on cultural politics. Progressives told themselves they were doing “anti-racism,” which at a sufficiently high level of abstraction is something Hispanic voters should appreciate since they say they experience racism and it’s bad.

But it turns out people are kind of selfish, and the predominant view among Hispanics is that we should talk more about racism against Hispanic people and less about racism against Black people.

That is a tough one to operationalize. But I think it illustrates why the traditional pragmatic view has been that it’s better to talk about race-neutral economic redistribution because the politics of explicitly centering race get very difficult and ugly very quickly. The good news is that old-fashioned ideas like raising the minimum wage and taxing the rich to finance an expansion of the welfare state really do close racial gaps in outcomes while also holding some appeal to low-income white voters.

Old-fashioned identity politics

I did an event last week where a cranky conservative person was getting angry about “identity politics” and expecting me to agree with him.

But something progressives say that I agree with strongly is that more or less all politics ends up being identity politics. But progressives need to live up to that. After an election where Democrats saw significant slippage with Hispanic voters, Biden proceeded to assemble a team where none of the really prominent White House senior staff jobs are done by people with Latin American ancestry. During the transition, I and a lot of other people thought Xavier Becerra would be tapped to serve as Attorney General specifically because there weren’t really any strong Hispanic candidates for Secretary of State, Defense or Treasury. But that job went to Merrick Garland instead, so Becerra got Health and Human Services as a kind of consolation prize.

Given the continued salience of the Covid-19 pandemic, you could imagine a world in which the HHS Secretary is actually an incredibly prominent and widely influential leader of America’s public health efforts. But that’s not really how Becerra is being used, in part because nothing in his background suggests he’s particularly well-suited to that job — he’d have made more sense as Attorney General.

And this all loops back around to the Latinx question.

One way to construct the identity struggles in American politics is that they pit white Christian gender traditionalists allied with big business against a big tent coalition of racial and religious minority groups, feminists, gender non-conforming individuals, and the poor.

Here’s a speech Jesse Jackson gave to the Democratic National Convention in 1988 that I think was too edge and left-wing for 1988 but is pretty well-suited to the 21st century.

When I was a child growing up in Greenville, South Carolina, and grandmamma could not afford a blanket, she didn’t complain, and we did not freeze. Instead she took pieces of old cloth—patches, wool, silk, gabardine, crockersack—only patches, barely good enough to wipe off your shoes with. But they didn’t stay that way very long. With sturdy hands and a strong cord, she sewed them together into a quilt, a thing of beauty and power and culture. Now, Democrats, we must build such a quilt.

Farmers, you seek fair prices, and you are right—but you cannot stand alone. Your patch is not big enough. Workers, you fight for fair wages, you are right—but your patch labor is not big enough.

Women, you seek comparable worth and pay equity, you are right—but your patch is not big enough. Women, mothers, who seek Head Start, and day care and prenatal care on the front side of life, relevant jail care and welfare on the back side of life, you are right—but your patch is not big enough.

Students, you seek scholarships, you are right—but your patch is not big enough. Blacks and Hispanics, when we fight for civil rights, we are right—but our patch is not big enough. Gays and lesbians, when you fight against discrimination and a cure for AIDS, you are right—but your patch is not big enough.

Jackson is aiming, in math jargon, to construct the union of all these different identity groups — everyone who is gay or Black or a farmer or a feminist — into a coalition that will collectively be strong enough to meet all of its component elements’ core needs. That is hard to do, but it’s a winning strategy if you can pull it off, and I think Obama to some extent delivered on the path Jackson outlined.

I don’t think there is a super obvious and unequivocal answer as to how you construct a coalitional proposition such that everyone in the quilt is getting enough to make it worth fighting for, but not so much as to alienate other coalition members. But I do think it’s pretty easy to tell when movement leaders aren’t even bothering to try.

I am blessed to not only have a decent amount of Hispanic friends from growing up in Los Angeles, the military and in Idaho, but I spend 3-4 months a year working in Latin America side by side with Mexicans, Venezuelans, Peruvians, Colombians, Brazilians, and Argentinians. I've basically spent the last three months working in Salta, Argentina.

I viscerally hate the term Latinx. Mainly because it's primarily used by a certain type of pandering progressive type. The stereotypical liberal, in which there is rarely any useful debate to be held. Even worse is when it's used by politicians or business leaders who associate with this crowd, and clearly have no close associations with the Hispanic community in the United States.

First, for the rest of my rant, I am going to use the term Hispanic, because it covers everyone except Brazilians.

Observations:

Even though I prefer the term Hispanic for the United States, in the rest of Latin American, it's not commonly used. Generally, the people are more likely to refer to themselves by their nationality first. They are Colombians or Argentinians. This national identity is much stronger than any allegiance to any group. If pressed, or when talking about people from multiple countries, Latin Americans is the term used most (which is gender neutral... thus my annoyance at coming up with another term). Latino or Latina is popular though it's more popular the further north you go and fades as you move down south.

The whole gender neutral latinx (latine') is used by the progressive college crowd, though only in that very small subset of population, and is never used by media or in the mainstream.

My favorite story is working with a Mexican engineer (recently immigrated) in the United States one time at a job site, and discussing the term Latinx. His reply "pinche gringos"

On to what I observe among Hispanic-Americans and politics in the United States.

For the longest time, it seemed to me that Hispanic representation in politics seemed to be dominated by the East Coast. Cubans, Puerto Ricans, etc... which never really translated to the issues of the mostly Mexican and Central American heritage Americans that I grew up with in Los Angeles and who I worked with in the Military.

This is slowly changing as more Americans with Mexican Heritage enter politics. I fully expect this influence to increase exponentially.

If you ask me, our countries focus on Black White issues almost seems to exclude Hispanic Americans from discussions.

Even in the media and entertainment, I am constantly annoyed at how poor representation is of Hispanic Americans. And even when it does happen, it's rarely reflects reality. It focuses on recent immigrants (there are a whole lot of 2nd and 3rd generation) Americans.

These days TV sitcoms routinely have both white or black characters (unlike Friends), but it's a lot rarer for them to have a Hispanic character, even though at least in my life... it's fairly impossible to live your life without Hispanic friends/co-workers.

My observation is that my Hispanic friends tend to range from very conservative to moderate. With the vast majority sort of in the middle. Liberal Hispanics are rarer than white liberals, and if they do exist, they are going to come from the highly educated college crowd.

The Hispanic vote is never going to be as monolithic as the black vote, but to win these voters, it seems to me that it's bread and butter issues that are going to win the day. The sort of social support programs that benefit working people, allow them to get ahead.

Finally, one of the key mistakes Democrats make when trying to attract the Hispanic vote is assuming that an openish border policy is going to be the main issue. First, Hispanic voters are American citizens, and by definition they were either born here, or followed the process and rules. Secondary, even undocumented migrants can understand supply and demand as far as wages go. They have no real economic reason to want even more undocumented migrants vying for the same jobs that they are performing. However, providing a path to citizenship and allowing family to migrate as well are key issues.

If politicians really want to win the Hispanic vote, then they need to do the same things that are going to win the white working class vote and the same things the black working class want as well. Material over identity.

As usual I think you're basically correct, but... Yes, Latinx is more a symptom than "the problem," but in my view it's a symptom of a really serious problem. A faction of progressive Democrats have become enamored of cultural issues I perceive as being not merely politically counterproductive but often factually incorrect and/or morally flawed. Remarkably, despite their modest numbers, the faction has become so powerful within the party and within the "liberal punditocracy" that their unwise actions are leading the Democratic party to catastrophe, with terrible consequences for the country.