Harvard will never be an engine of social mobility

What the new Ivy+ admissions paper really shows

The student bodies at America’s top colleges are overwhelmingly skewed toward children of the affluent.

Looking at the Ivy+ set of colleges — the eight Ivy League schools plus MIT, Chicago, Duke, and Stanford — a staggering 42% of the class is drawn from households in the top 5% of the income distribution. And though these schools account for just 0.8% of all American college students, they generated 11.6% of current CEOs, 26% of the staff of the New York Times and Wall Street Journal, and 71.4% of recent Supreme Court justices. This relatively narrow bottleneck for entry into the American elite is a powerful replicator of socioeconomic privilege. So when the Opportunity Insights project documented in a recent paper that students from the richest households are much more likely to be admitted to these schools than other students with similar test scores, it was a blockbuster finding even though it didn’t exactly surprise people.

This chart published in the New York Times based on the research, in particular, went extremely viral.

I’ve read the paper several times over the past week and honestly feel somewhat torn about it.

On the one hand, the researchers are documenting something real. Legacy preferences, athlete recruiting, and a tendency to mysteriously rate private school graduates’ non-academic qualifications as systematically stronger than those of public school graduates all create a significant bias in favor of rich applicants. It would be desirable for the schools in question to do what Raj Chetty, David Deming, and John Friedman recommend and adopt a more egalitarian approach.

That said, I worry that these findings are being broadly overread by the public.

If you read the full conclusions of the paper, it turns out that eliminating these sources of bias has a relatively modest impact on the overall composition of Ivy+ classes. It also turns out that the causal impact of attending an Ivy+ school is pretty modest. Rich kids’ disproportionate presence in the Ivy+ schools is mostly accounted for by their higher test scores, and Ivy+ grads’ disproportionate success is also mostly accounted for by their higher test scores. Monkeying around with admissions policies would make some difference, but it’s not really much of an egalitarian agenda.

If you want to create a more equitable society, you ultimately need to look elsewhere — at redistributing material resources away from the most elite schools and away from the richest people.

Admission reform has very modest results

I am not normally a big fan of scolding people about truncated y-axes.

And I also don’t want to complain too much about this paper, because it is by far the most rigorous, detailed, and informative look that we’ve ever had at a topic that generates a lot of interest. But when I look at their bottom line simulations in terms of how different the Ivy+ schools would look if they eliminated bias from the admissions process, these seem like small changes that look large thanks to a truncated y-axis. They are telling us that if we eliminate legacy preferences, eliminate preferences for athletes, and eliminate the skewed ratings of private school grads, we would end up with a world where 33% of Ivy+ students are from the top 5% of households.

That’s an overrepresentation of more than six-fold.

Now look back to that dramatic NYT elephant chart showing that controlling for test scores, children of the elite are 2.2 times more likely to be admitted than middle class kids. That was a striking chart. But eliminating that bias leaves the majority of the disproportionality in place. In statistical terms, the largest reason rich kids are overrepresented at the top schools — by far — is that the rich kids have higher test scores.

In terms of ongoing college admissions controversies, I think this fact is probably more important for people to know than the bias that they identify. I might be wrong about this, but my sense of the world is that most people are pretty cynical. There are not a ton of naive people out there who believe that American society is a pure meritocracy who are going to have their world rocked by the knowledge that graduates of expensive prep schools get a leg up in life. But I think there actually are a huge number of cynics who think the whole system is incredibly rigged, that elite education is basically fake, and that the Ivy League is just a bunch of rich dopes hanging out getting plaudits they don’t deserve. There’s also a large group of sub-cynics who think that standardized testing is fake and the fact that rich kids have higher scores shows that test prep classes work magic or something. That’s the impetus behind the move to scrap standardized testing in admissions.

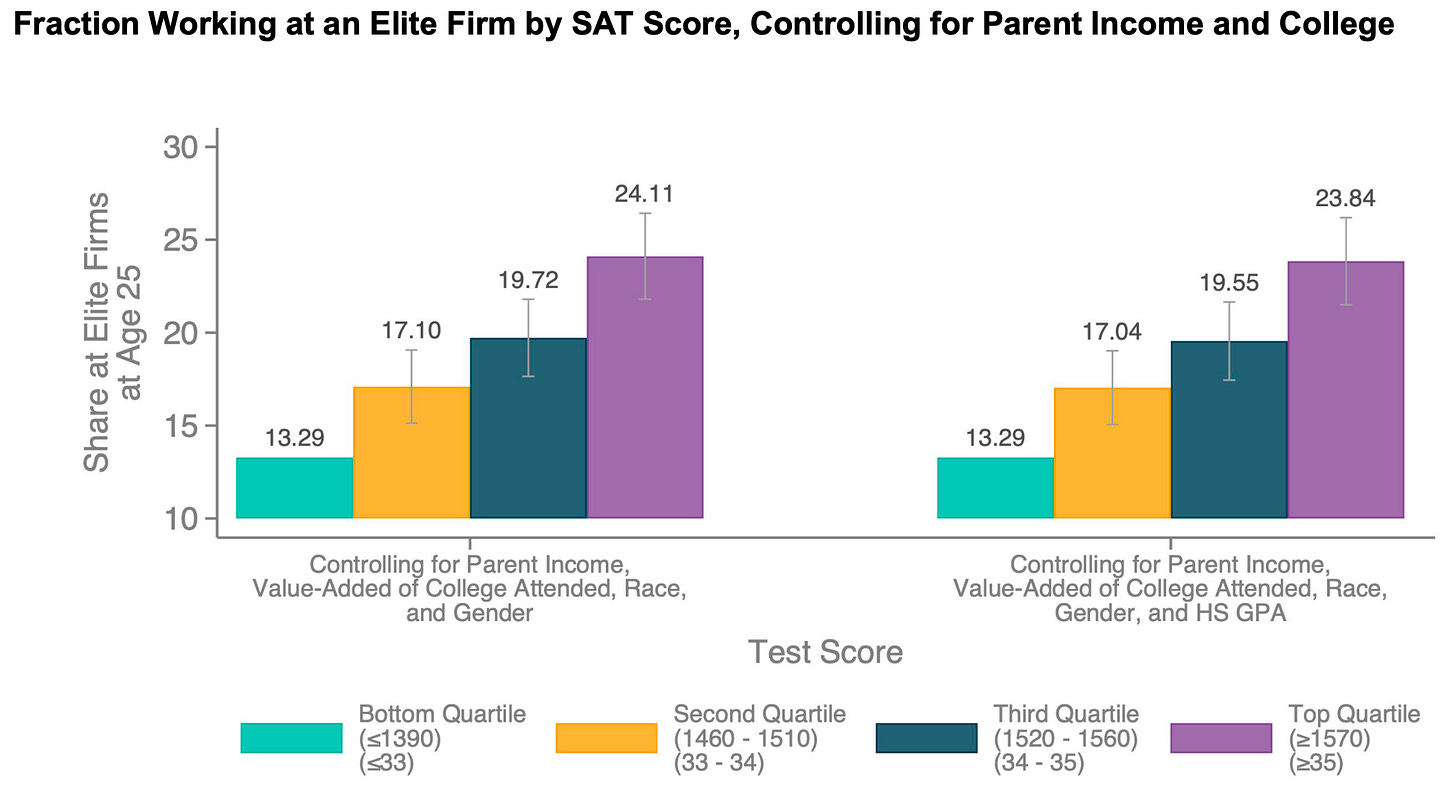

Test prep is, obviously, a real thing. But one thing the Opportunity Insights paper confirms is that high SAT scores are broadly predictive of a range of positive outcomes, even when you control for parental income and for college attended. The people in the top quartile of the SAT distribution are generally smarter than the people in the bottom quartile, and smart people tend to do well in life.

There is a feedback loop here. Because smarter people are more likely to be rich, rich people are more likely to have smart kids and are more likely to invest the time and money in getting their kids the best schooling — plus access to the best public schooling is auctioned through the real estate market. And while Ivy+ graduates are overrepresented in various elite circles of American life, the main reason for that is they have (on average) much higher test scores than the average person.

The causal impact of fancy college is modest

A classic paper by Stacy Dale and Alan Krueger notes that graduates of the most selective colleges have higher incomes than the graduates of less-selective colleges, but then asks how much of that is pure selection effect versus the causal influence of college. They measure this by looking at people who for whatever reason chose to attend a less-selective school than the best one they were admitted to and comparing them to similar people who went to the more selective schools. They find that “estimates of the return to college selectivity fall substantially and are generally indistinguishable from zero.”

But that’s not true for everyone. They do find that “for black and Hispanic students and for students who come from less-educated families (in terms of their parents' education), the estimates of the return to college selectivity remain large, even in models that adjust for unobserved student characteristics.”

So that’s Dale & Krueger.

Rich kids may have a leg up in attending the most selective schools, but they don’t benefit from attending the most selective schools. Going to a fancy college is a useful networking experience if you’re not from a fancy family, but if you’re from a fancy family then you already have the network.

Chetty/Deming/Friedman confirm that there is no causal boost to average income from attending an Ivy+ school but argue that it makes a difference in terms of right-side outliers. They have a somewhat more complicated method for assessing causation that involves looking at quasi-random variation in who gets off the waitlist, and show that getting into an Ivy+ school increases your odds of making it into the top 1% of the income distribution by your early 30s.

Your mileage may vary as to whether this seems like a large effect or a small one to you. But, again, I would urge everyone to note the y-axis. This research indicates that the large majority of Ivy+ grads’ tendency to land in the top 1% is a selection effect rather than a treatment effect. Now they do show larger impacts for your odds of attending a top graduate school and for the odds of working at what they call an “elite” or “prestigious” firm.

This is interesting, but it’s also worth noting that this elite/prestigious firm business is defined in terms of employing lots of graduates of Ivy+ schools. So they’ve clearly demonstrated that actually attending Harvard gives you a boost in getting hired at a place that employs lots of Harvard graduates. It’s extremely cool that they can quantify this so precisely. But again, I think that relative to the conventional wisdom, the most important part here is confirming Dale/Krueger.

If I’m doing my math right, sending your kid all the way through Sidwell Friends costs nearly $700,000, which seems to me like a lot to spend for a modest increase in his odds of attending a college which will, on average, provide zero boost to his earnings.

What are we doing here?

Now I want to step back and say that I agree with the authors that the pattern of skewed admissions they note is bad.

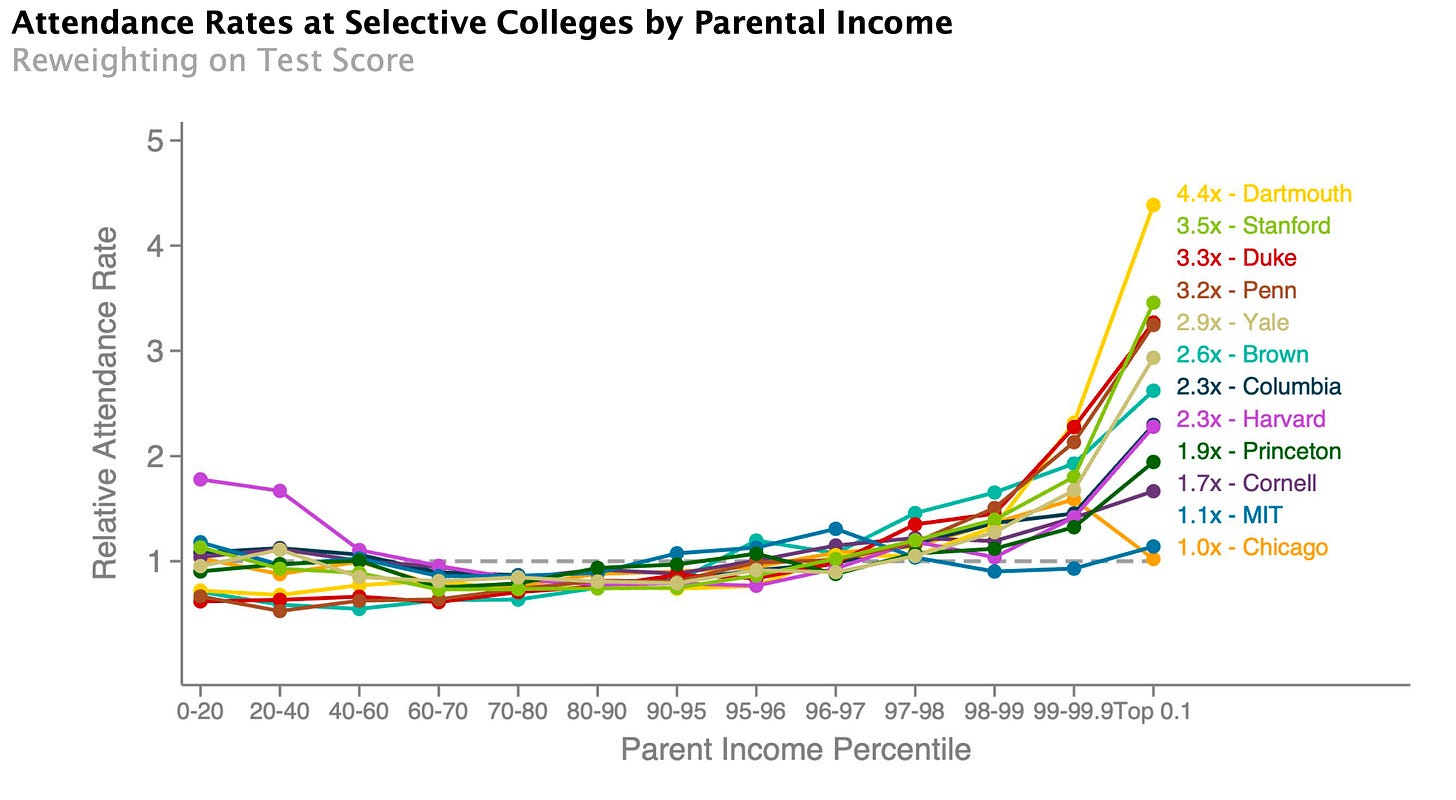

One noteworthy thing that they show is that practices are not uniform in this regard. MIT and the University of Chicago, in particular, basically don’t do this. Harvard and Princeton are better than Duke and Stanford.

So my official recommendation to all billionaires considering making a large financial contribution to a prestigious university is that you should give you money to MIT or Chicago. And if you attended one of these other schools and/or live in the city where they are located, you ought to send a note to the relevant development office talking about your donation to MIT/Chicago and explaining that the reason you gave to MIT/Chicago rather than your alma mater is that you do not approve of the class skew of their admissions practices and you think they should change. Chicago, in particular, is also fortunate to be operating in a less NIMBY environment than MIT, and I think billionaires should give them money to keep expanding the size of their undergraduate class and if necessary talk to Brandon Johnson about why his administration should support this.

Meanwhile, Dartmouth and Stanford alumni should call up the alumni office and say this chart makes them look bad and they should fix it. All the elite schools that have permission of their local government should expand the size of their undergraduate class, and elected officials should be encouraging rather than (as is often the case) discouraging it. So that’s my pitch for increasing social mobility via elite college admissions. Let’s do it.

But I think it’s important to have a sense of perspective here. Even under a sharply reformed system, the Ivy+ colleges are not going to be engines of social mobility. Donors who really care about social mobility in higher education should be giving money to flagship state universities and to the public colleges on this list that tend to serve immigrant-heavy communities with above-average efficacy. It also might be good for state legislatures in the northeast to think about whether it wouldn’t make sense for New York and Massachusetts to try to invest the money needed to create prestigious flagships, along the lines of those in Michigan and Wisconsin and Texas and California.

Fundamentally, though, you come back to the themes of my Strange Death of Education Reform series about improving public education. This proved to be a substantively difficult and politically unrewarding task. But it’s actually very important! The victims of the inequities identified in this paper — kids with good grades, 1500+ SAT scores, generally from families in the 70th-80th percentile of the income distribution — do perfectly well in the United States of America. The much larger problem is poor kids for whom K-12 school quality makes a huge difference but who often don’t have access to the best teachers or the best curriculum. This doesn’t key into the personal identity issues of New York Times subscribers in the same way that arguing about Ivy League admissions does, but it’s much more important.

What we really need to do is just put a social stigma on hiring Harvard or Ivy League graduates.

I also think that Matt might focus a little too much on income, I suspect being a graduating or attending an Ivy League also increases the odds of getting an influential job.

For instance, I have a brother-in-law that runs a construction company that clears over seven figures, but he is not nearly as influential as say Matt is.

Matt has hired two awesome interns, but for whatever reason both of them have come from well to do families and attended Ivy League schools. I have to imagine that writing for Slow boring will give them a boost up if they decide to go into politics or public policy or writing. However, I also have to wonder if there are not more talented riders out there that didn’t attend Ivy League schools, that just didn’t have the connections to get the job.

No, I am not coming at Maya or Milan, they are hard driven talented young adults. Just pointing out how the world works.

Hierarchy is sustained by three powerful forms of inheritance-- genetic, cultural and financial. The combined force of inheritance+ is so powerful that policy tweaks will do little to curb it. Even communist regimes have disproportionate numbers of brahmins in charge-- Lenin was the son of an aristocrat, Ho the son of a senior civil servant, Che of a doctor and Castro of a haciendado. Even Mao was the son is a self made kulak. The only way to seriously curb privilege would be to stunt or ostracize those from good families, and, even if politically possible, it would give us a far less capable professional class.

The focus should be on providing good lives for people in the bottom half of the status distribution, not on obsessing about who gets into the 1% versus merely the 3%.