Harris is right on the merits about fracking

Energy abundance is bigger than Pennsylvania's electoral votes

Kamala Harris does not want to ban fracking. Under the Biden-Harris administration, the United States is pumping record amounts of oil and record amounts of natural gas, even as solar installations soar and crucial progress is made on advanced nuclear and advanced geothermal.

Democrats now overwhelmingly understand that they need to say this about fracking, and some (though by no means all) are even willing to boast about oil and gas production. But to the extent that they embrace this tactic, it’s largely because they’ve been told that fracking is politically important in Pennsylvania. So we get takes like David Roberts questioning the wisdom of the pro-fracking stance by noting that there are more direct jobs in Pennsylvania clean energy than in Pennsylvania fracking, or leftist climate communications guru Genevieve Guenther saying it’s bad to give in to Republican “framing” about this.

And I want to push back on this a bit.

It’s of course true that fracking is economically important in parts of Pennsylvania, and that Pennsylvania is a very important state. But even if North Carolina or Arizona emerges as the pivotal state in the 2028 election, it would still not be a good idea for Democrats to ban fracking. Nor is this a question of framing.

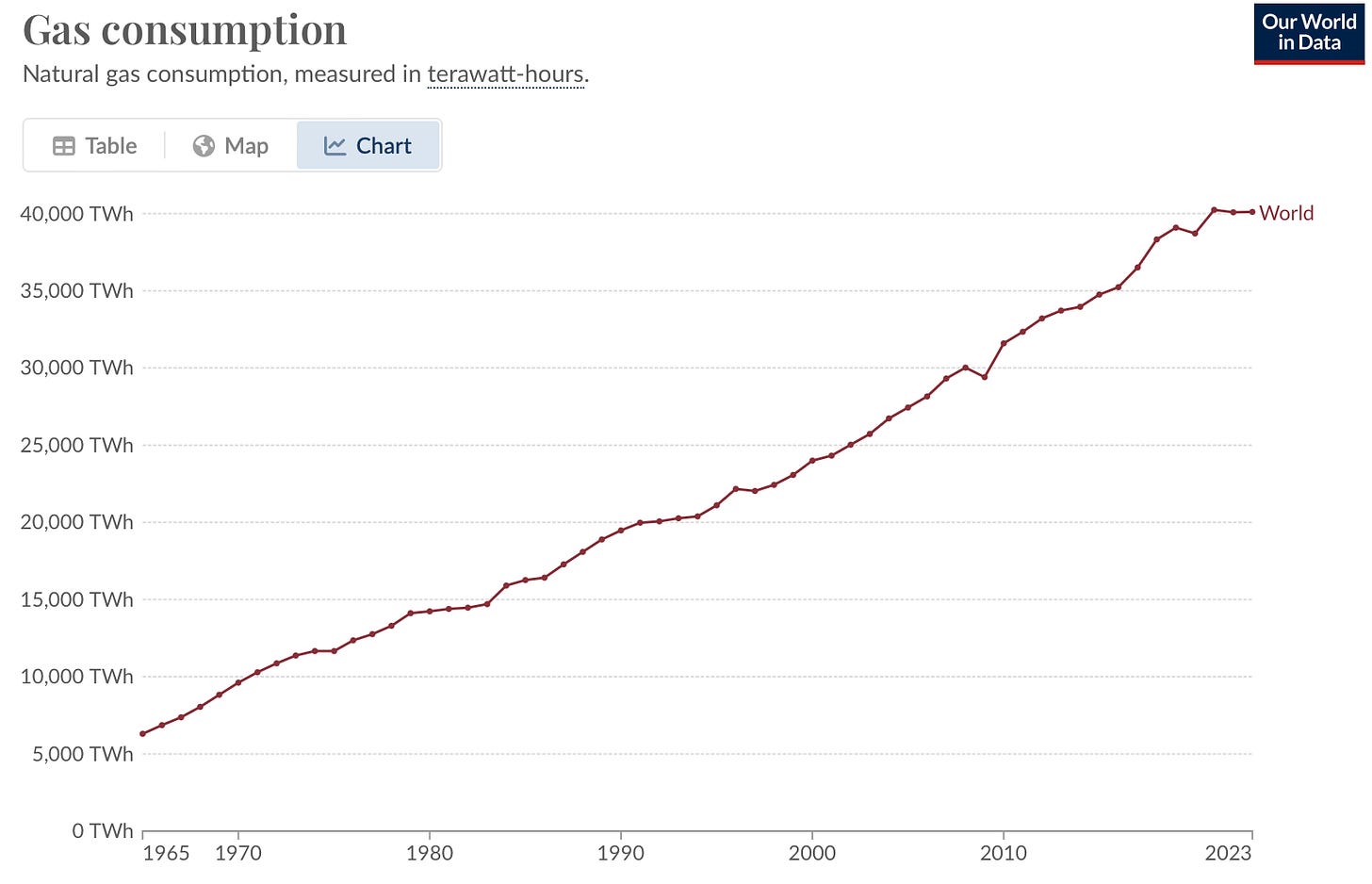

America should not ban fracking, because fracking is a means of obtaining oil and natural gas, two extremely valuable commodities. The utility of oil is currently declining due to improvements in battery technology, but robust demand for oil will continue for the foreseeable future. And though global natural gas consumption has leveled off over the past few years, I think it’s likely to start rising soon due to increases in electricity demand.

Either way, the world is using oil and gas in 2024, and will be using oil and gas in 2025, 2026, 2027 and so on. There are very good reasons to try to speed the pace at which the world reduces its consumption of fossil fuels, and there are plenty of reasonable policy measures that can help achieve that. But to the extent that the world continues to use oil and gas, it is the correct policy for the American economy, and for the world’s environment, for the United States to produce a larger share of that oil and gas and for foreign autocracies to produce a lower share.

Democrats should own this policy proudly, exploiting it to maximum electoral effect in Pennsylvania (and Texas), but also seeing it as a correct policy idea, not a grudging concession made to the electoral map.

We’re going to keep using oil for a while

Nobody knows the exact future of global demand for any commodity, but because rich people with money on the line want to make decisions about investments, a good amount of work goes into trying to guesstimate the future. I wouldn’t take an investment bank research note on any subject as oracular prophecy. But they’re good to look at because they represent good-faith efforts at forecasting by people whose financial incentives lead them to try to be accurate.

David Ernsberger of S&P Global Commodity Insights says that “by 2050, oil demand will be about where it is today.” Goldman Sachs says that global oil demand will peak around 2034, though I think that may be wrong based on the apparent decline in Chinese oil demand.

Right now, most people (especially in America, where gas is cheap and very large vehicles are the norm) don’t want to switch to electric cars. But a lot of the forecasted increase in demand comes from poor countries that are getting less poor and where people are driving more. Current EVs are good enough and cheap enough that it seems totally plausible that many who currently rely on bikes or dirty scooters will upgrade to small, cheap, electric cars, and peak oil could come in 2030 or earlier.

But even when that happens, we’re still looking at years of oil usage. An average car lasts 12 years, so even if the Walz Administration bans the sale of internal combustion engine cars in 2033, plenty of old ones will be on the road into the 2040s. There isn’t currently any viable technological substitute for using oil to power jet planes, and the planes rolling off the assembly line from Boeing and Airbus last for decades.

Maritime shipping is important. Heavy trucks and other industrial equipment are important. There’s a kind of weird discourse in which hardcore anti-greens insist that these are unsolvable problems, which leads environmentalists to push back and talk about all the promising initiatives in these arenas. And they’re right, there are promising initiatives; I think these problems will be solved. But they’re not currently solved, or even on the verge of being solved.

We’re going to need oil for a while.

The case for gas is even stronger

Hostility to oil production at least makes sense to me emotionally, because all this oil that we’re burning really is bad for the air, and existing electric car technology is ready to go. Lots of people don’t want to buy an electric car, because it would be a pain to need to charge it during long road trips (this gives me pause, personally), but if we had to do it, we clearly could, so the environmental community is frustrated.

But on any realistic account of how the global economy works, natural gas isn’t even bad for the environment. Right now, the world is burning enormous amounts of coal for both electricity generation and metallurgical purposes.

Coal is incredibly polluting, and driving it off the electric grid should be a top priority for global environmental policy.

At the same time, global electricity demand is set to rise. A lot of recent discourse focuses on the role that AI plays in this, which is important. But there’s also the fact that an enormous share of the world’s population continues to live in a state of dire energy poverty, from which we would like them to escape. And, of course, a big part of the climate solution is precisely to electrify things like home heat and transportation. A power plant is much more efficient than an internal combustion engine or a little furnace in your basement, so the environmental gains of replacing a gasoline-powered car with an electric one are real, even if the electricity comes from coal. But if the electricity comes from gas instead, it’s a bigger win.

Of course, it’s an even bigger win if the electricity comes from renewables (or hydro or nuclear). But because gas and renewables face different constraints in terms of construction, utilities don’t face an either/or choice between gas and renewables. Doing both lets you add more electricity faster. That’s especially true because the availability of gas-powered plants reduces the cost of building renewables, which would otherwise require massive overbuilding to meet edge-case reliability concerns.

Unless you’re just going to give up on economic growth (which Democrats haven’t and shouldn’t), then it’s desirable for the world to burn more gas, because the real-world alternative to that involves burning more coal.

There’s also the metallurgical situation.

Right now, making steel out of iron typically involves burning a lot of coal. But there’s another way to do it called “direct reduction,” which is typically done with gas. Direct reduction produces a type of iron that can be used in an electric arc furnace (EAF), a kind of facility that currently is mostly used to recycle scrap metal. The deep decarbonization vision is that we run all our EAFs off of zero-carbon sources, get all our basic steel through direct reduction, do the direct reduction with hydrogen rather than gas, and get that hydrogen using electrolysis powered by zero-carbon electricity. And that’s a great vision. But until we have such incredibly abundant zero-carbon electricity that it’s affordable to manufacture huge quantities of hydrogen, gas isn’t just useful, it’s cleaner than the alternative approaches. If you drop the bad habit of reasoning backward from semi-arbitrary emissions targets and just look at the actual impact of your policy choices, blocking gas production doesn’t make sense.

It matters where energy is made

As long as the world is using oil and gas, one reason to want that oil and gas to be made in the United States is jobs. But per Roberts’s point, the direct employment impact of fossil fuel extraction is pretty small. In economic terms, this is actually one of the virtues of fossil fuels — extracting them is a high-productivity undertaking that generates a lot of energy relative to the labor inputs.

But there are other benefits to producing energy at home rather than importing it from abroad.

One is the impact on terms of trade. Back fifteen, twenty, or twenty-five years ago, when the United States was a huge net importer of oil, we had a big problem any time the global price of oil spiked. Short-term oil demand is not very elastic, so the dollar value of oil imports would soar, pushing the trade deficit way up and negatively impacting Americans’ living standards. Now that the US is a net oil exporter, our economy is able to ride out price shocks without disastrous consequences. It’s still annoying to consumers when gasoline gets more expensive, but the American economy continued to grow through two different oil price shocks in the post-Covid years.

Another is proximity benefits.

Because natural gas is a useful input in various industrial processes, easy access to abundant natural gas bolsters a wide range of domestic manufacturing. One can concede the point that our long-term policy objective should be to develop cost-effective ways of doing these things that don’t involve gas. But you accomplish that by developing the cost-effective alternative, not by strangling domestic energy, and domestic manufacturing along with it so that equally dirty stuff gets imported from abroad. The global nature of the climate problem is annoying and inconvenient. When Al Gore titled the movie “An Inconvenient Truth,” he wasn’t wrong, climate change is genuinely very inconvenient. But it’s still the reality. As long as the gas is being used, it may as well be us using it.

Finally, energy has national security implications. European reliance on Russian gas has undermined the defense of Ukraine. It’s true that Europe is to some extent accelerating renewable deployment in response, which is great. But, again, it’s not like Europe is at a zero coal usage equilibrium. Gas plus the same renewables investment would be a better result. Indeed, one huge climate problem is that in recent years, China has substantially increased its already high coal usage, even as they’ve also deployed tons of renewables. That’s because China doesn’t have much domestic gas and doesn’t want to rely on imports.

That, of course, speaks to the poor state of US-Chinese relations. But to the extent that we can export gas to other, friendlier countries, that will help cement relationships. To the extent that we don’t, those countries will rely more on coal and more on Russia and Qatar.

A good, prudent policy

Recognizing the virtues of domestic fossil fuel production, as the Biden-Harris administration has, doesn’t mean ignoring environmental considerations.

The centerpiece of the Biden-Harris climate agenda has been huge investments in technology and deployment to reduce long-term demand for fossil fuels. That is a correct and important step. The budget deficit is also high and rising now, which is a problem that Donald Trump would make much worse, but that we should be making efforts to improve. Carbon pricing would further reduce fossil fuel demand while helping to address America’s fiscal problems. I concede that nobody wants to talk about this because it’s unpopular, which is fair enough. But the reason it’s unpopular is people don’t like it when energy gets more expensive. Supply-side fossil fuel policy has the exact same downside and also doesn’t generate any revenue. So I’m not saying climate hawks should be pursuing carbon pricing — political caution is warranted — but if you do want to run the political risk of making energy more expensive, you should at least do it in a way that makes sense.

Meanwhile, the administration is also moving to implement prudent regulation of the extraction process itself — cracking down on methane leaks, for example, and ensuring that US production is much cleaner than its foreign rivals.

I would like to adjust policy to be a bit friendlier to American fossil fuel extractors. But the first step in making that happen, I think, is to convince Democrats to be less sheepish about the fact that they haven’t given in to demands for a huge crackdown. They ought to see this as a balanced, prudent policy that is worth proudly articulating and whose logic they should take seriously. Instead, they often seem to see it as a shameful compromise with political necessity or the specific dictates of Pennsylvania. It’s not. It’s simply a correct analysis of a difficult problem.

The model to emulate should be something like the approach of the center-left government of Norway, which is way ahead of us in terms of reducing their domestic fossil fuel demand, but which continues to pump oil and gas for sale on the world market. The Norwegians take care of their genuine responsibility to the global environment, while also recognizing that it is better, not just for Norway, but for the entire world to have fossil fuel resources controlled by a responsible democratic state with good values rather than by Venezuela or Iran. The United States is new to the game of being a fossil fuel exporter but should try to emulate that ethic — investing in innovation and targeting demand, and also supplying the world with the energy it needs, while it needs it.

you and noah smith are right on this, and nice to see the centrist-left pivot away from the viscerally anti-fossil fuel enviros.

yglesias award winners :)

The (perhaps) only good thing about Trump is that he unifies the Democratic Party in a way that encourages people like David Roberts and Bill McKibben to pipe down and get in line.

Relatedly, today's Axios posting¹ leads with "Dozens of immigration and progressive groups believe Vice President Harris' recent hawkish immigration policy pledges are 'harmful' and part of a 'MAGA anti-immigrant agenda' — but many are backing her anyway."

The coming intra-party fights, post-Trump, are going to be epic.

¹ Link: https://www.axios.com/2024/09/18/harris-border-shift-immigration