Don’t let Elon Musk monopolize space compute

A case for more antitrust enforcement

Last week, Elon Musk announced plans to merge xAI and SpaceX, a move that did not attract much political attention despite the intense levels of interest in arguing about both antitrust policy and Elon Musk.

At the same time, SpaceX has begun the process of securing F.C.C. approval for a plan to put orbital data centers into outer space.

I think one reason this hasn’t attracted a ton of attention is that the idea of putting data centers in outer space sounds kind of fantastical. Another is that progressive politics has become strongly associated with A.I. skepticism, so the idea that you’re going to build a vibrant business by launching data centers into space and there may be an antitrust issue with this doesn’t quite scan with the right people.

But we should take the economic possibilities of A.I. seriously.

And while I’m kind of skeptical about the space-data-centers idea as a short-term play, plenty of people in the industry think it’s worth taking a hard look at. There are some big problems with space as a location for data centers, but also some real upsides.

As a result, this merger poses the very real risk that the combined company will be able to leverage a dominant market position in the space launch industry into a dominant market position in A.I. If nothing else, that is clearly what Musk wants to achieve with this merger.

That is bad in a classic antitrust sense. It’s good for the United States and the world to have a competitive A.I. market, one where OpenAI and Anthropic and Google and Meta and others are robustly competing at the frontier. The potential for A.I. in space is real, and allowing a single company to monopolize that would be a big mistake.

By the same token, while antitrust issues have become a factional wedge in the Democratic Party, I think it would make more sense to target regulatory activism at evil right-wing billionaires rather than maintain an exclusive focus on antagonizing Democratic donors.

All of which is to say, an xAI / SpaceX merger ought to be prohibited.

Beyond the fact that Musk is the founder of both companies, the only rationale for merging them would be an anticompetitive one. But beyond that (or if it ends up being too late to block them), Congress ought to act to impose common-carrier regulatory requirements on SpaceX. Which is to say that while they should be free to charge what they want for the use of their space launch capabilities, they should be forced to offer publicly listed prices on a non-discriminatory basis. No special access to space for Musk’s other businesses.

This is how telecommunications infrastructure has historically been regulated, and it’s also how railroads were regulated during their heyday as mission critical infrastructure.

Space launch does not strike me as an inherently monopolistic industry and if it grows to three or four viable players in the future, we could consider rolling these rules back. But for now, SpaceX has a significant lead that may get bigger before it gets smaller due to their new launch vehicle, Starship. That’s an impressive achievement and they deserve to make plenty of money off of it. But they should not be allowed to leverage it into dominating whole other industries.

The final data-center frontier?

For more background on space data centers, I recommend Dwarkesh Patel’s good discussion of the issue with Musk in his most recent podcast episode.

But the basic case for space, as I see it, is two-fold:

Once you can launch something into space, providing it with 24/7 solar power is very cheap because solar panels are now inexpensive and in space there’s no weather or nighttime.

Earth-bound permitting and NIMBY issues are bound to escalate over time. These are already significant, but the battle against them has, so far, largely involved the lowest-hanging locational fruit. I think it’s fair to say that whatever problems these issues are causing in 2026, the situation will be worse in 2028 and even worse in 2030 if the data-center buildout continues.

Musk’s move is premised, at least implicitly, on the notion that the current aggressive data-center buildout essentially never ends: Not only will we want to train new models, but once they are trained we will want to use them a lot, and not just to do “computer stuff” as in current A.I. applications, but to run vast armies of robots. The future robot population will be limited by manufacturing capacity but also by the capacity to harness energy to run A.I. inference.

And the best way to harness maximum energy over the long-term is to be in space.

In the F.C.C. filing, SpaceX says that “launching a constellation of a million satellites that operate as orbital data centers is a first step towards becoming a Kardashev II-level civilization — one that can harness the sun’s full power — while supporting A.I.-driven applications for billions of people today and ensuring humanity’s multiplanetary future.”

This is a reference to the ideas of Soviet astronomer Nikolai Kardashev, who described three types of possible civilizations:

A Type I civilization is planetary and able to access all the energy available on a planet and store it for use.

A Type II civilization is stellar and can directly consume the vast fusion power of a sun with a Dyson sphere.

A Type III civilization is galactic in scale and can capture all the energy of every star and other object (black hole, etc.) within it.

While talking with Patel, Musk had a lot of thoughts about interconnection queues and very optimistic takes about the falling cost of space launch. Musk has a tendency to over-promise what his companies will be able to deliver, and I think we should discount his stated timelines around this. But his basic observation about the long-term trajectory of energy supply could hold regardless.

Energy is more accessible in space than it is on Earth, so there is some level of space launch capacity at which it makes sense to put energy intensive applications (especially those that do not require breathable oxygen) out there rather than down here. Casey Handmer did some math here and comes up pretty bullish on this as a short-term idea, though a lot of reply guys say he’s underrating the difficulty of heat dissipation in the vacuum of space.1 I’ve been on the sidelines of some conversations with people who are more technical than I am that devolved into arguments about things like radiator structures.

My basic conclusion is that it’s hard to say.

The technical and logistical challenges to creating large-scale orbital data centers seem daunting, but so are the challenges to dramatically accelerating the pace at which such things are built on Earth. There are limited gas turbines available, there is political resistance to projects that raise electricity costs,2 and while bring-your-own solar solves the electricity cost problems, it means that the physical data-center footprint gets that much larger, creating even bigger NIMBY issues.

But the space idea is something that could pan out, and it would be a mistake to let affective dislike of Musk blind us to the possibility that he’s about to become even richer and more powerful.

Common-carrier rules for critical infrastructure

The United States (and other countries) have often required companies that provide critical infrastructure services to act as common carriers.

In the traditional telephone industry, anyone who wants a phone number can get a phone number. The phone company can charge you money to use their network, but they cannot discriminate in who they serve or on what terms.

This works for a few reasons. One is that some of the controversies that often arise with regard to internet companies just don’t apply in the common-carrier world of telephones. There’s no question of asking the phone company to censor “misinformation” that’s carried over phone lines. If Nazis or other bad people want to make phone calls, they’re allowed to do so. If it turns out that the mafia was using telephones to organize their criminal activities, the phone company is not legally liable for the work. The phone company has no legal responsibility — or even really social responsibility — to ensure that phone calls are being made only by good people or only to do good things. They have to cooperate with law enforcement in certain scenarios with wiretaps or records requests, but the phone infrastructure is neutral and broadly available.

The flip side of that, though, is that the phone company can’t engage in business shenanigans.

AT&T can’t say “accessing telecommunications infrastructure is important for the emerging computer industry, so we’re going to buy a computer company and then give that computer company privileged access to our telecom infrastructure.”

Railroads, similarly, were hit with tough common-carrier rules by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887.

The idea was that railroads should have to offer their services on equal and open terms to anyone who wanted to use their network to ship goods. The railroads could have all kinds of different pricing schemes and rules, but they couldn’t have special deals with particular companies.

There were a lot of different interest groups applying pressure on this, but the core idea was that rail shipping was a kind of narrow bottleneck, and while it’s fine to make ownership of the bottleneck lucrative, you don’t want to allow the bottleneck owner to extend control into other more competitive industries. Freight rail rules were relaxed in the 1970s in light of cross-mode competition from trucking, and while some people want to re-regulate the industry, I don’t think that’s a great idea.

By the same token, I don’t think space launch is an inherently uncompetitive industry, and I’m not a guy who’s just looking for pretexts to turn anything under the sun into a tightly regulated utility.

But the business plan that Musk is articulating here clearly indicates an aspiration to transform a short-term lead in space launch into an indomitable lead in A.I., and we should not let him do that. If his rockets can carry data centers into space in a way that makes for a cost-effective business, that’s great. But they should carry everyone’s data centers.

The merits of specificity

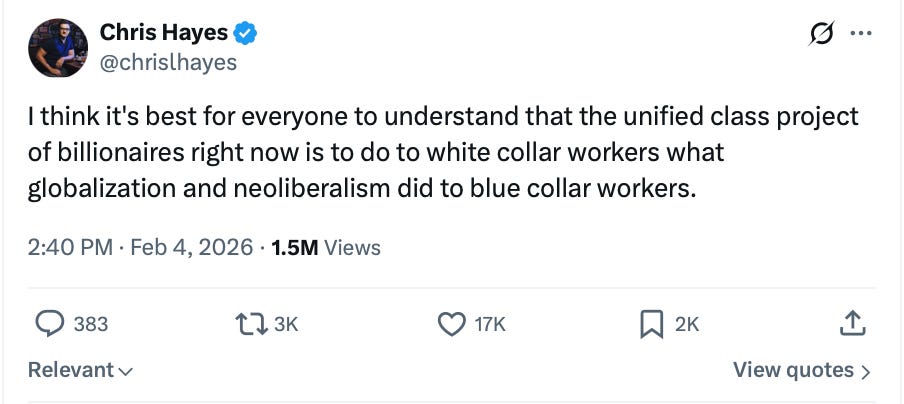

Chris Hayes remarked last week that “the unified class project of billionaires right now” is to immiserate white-collar workers in much the way that globalization and neoliberalism allegedly did to blue-collar workers.

I have a lot of quibbles with that characterization of globalization, but I think the “unified bloc of billionaires” worldview is politically naive in a way that’s more problematic.

Do billionaires have common class interests? Of course. At the same time, Musk is currently engaged in an intense legal struggle with Sam Altman and OpenAI. Everybody is angry at Jeff Bezos right now because of the split screen of his handling of the “Melania” documentary and the Washington Post, and that’s fair. But Bezos is also the closest thing that Musk has to a competitor in the space launch game. Altman and OpenAI have a close business relationship with Microsoft. Bezos and Amazon have a close business relationship with Anthropic. Google integrates a leading A.I. lab with a leading conventional technology company. There are lots of billionaires whose wealth comes from companies that could be put out of business by rapid advances in A.I.

My point here isn’t “not all billionaires” or even that some billionaires are great people who are highly charitable and working to make the world a better place. It’s to observe that even though I don’t find the behavior of Musk or Altman or Bezos during the Trump II Era to be particularly admirable, it’s still the case that these guys are fighting with each other in both business and politics.

Seeing our way to a better future will require political struggle. Some of that is mass politics and broad appeals. But sharp politicians have always found ways to play powerful interests off against each other and make space for the public interest.

Musk is trying to do something here that is bad for the country and the world and that is also bad for various non-Musk billionaires and corporate actors. We should try to put a coalition together to block him. Similarly, Trump’s various corrupt chip-export deals are bad for a partially overlapping group of billionaires and it’s important to work with them to put a stop to them. I get that “stop Elon Musk from assembling a hypothetical monopoly over space-based compute” is not quite as exciting as “liquidate the billionaires as a class.” But actual politics is just a bunch of specific things, not a bunch of vague slogans. There is a specific threat here that has specific remedies and there is a specific set of business elites who could and should be allies in addressing it. Let’s do it.

Here’s a discussion of the general issue if you are interested.

Notably, “bring your own generation” mandates only kinda sorta solve this if your solution regarding generation is to burn gas because you’re going to raise the price of fuel.

.....what on the Atlas Shrugged is going on here. There is not a market for either xAI alone nor for reusable rockets at present, and data centers in space is an idea that won't even see the first attempted launch for years. Yet it's so important that it must be the pursuit of anti trust legislation?? Like the other rail/utilities examples mentioned let's look to Congress to pass a law, there is literally negative proof of anti trust enforcement here. There isn't even a market!! Bad take.

This article presupposes that there are other AI companies out there with bold plans to put AI data centers in space but who will be blocked by SpaceX boxing them out on behalf of x.AI. Is that really a thing though? this seems like another Moon shot that Elon wants to try, and we should let him, and we should get out of his way. Just like with Tesla or SpaceX, he's doing something so bold and authentically innovative, that we should not preemptively put up roadblocks and create more regulatory uncertainity here--at least not for the reasons stated.

Let him prove his concept, like he did with rockets and electric cars. Then we can think about regulations after it hurts consumers or competition.