Denver’s restaurants are dying

Rising costs put independent full-service dining at a disadvantage

Happy Labor Day! Today’s post is from Slow Boring Writing Fellow Halina Bennet.

Restaurants across the country are struggling to stay open as costs soar and lingering post-Covid economic challenges force operators to shutter once-thriving businesses. In Washington, D.C., even before President Donald Trump’s deployment of federal forces drove away business, openings were down nearly 20 percent from last year and almost half of restaurants surveyed by a restaurant advocacy group said that they were likely to close in 2025. More than 100 restaurants shuttered in Los Angeles in 2024, and New York City saw all manner of companies across the city slow their hiring as business owners, restaurateurs included, struggled to afford payroll.

Perhaps no city better exemplifies the challenges facing the restaurant industry than Denver, where some of the highest prices in the country — for both operators and customers — are making it nearly impossible for businesses in the midsize city to stay open.

While intended to support workers, Denver’s high minimum wage, especially its low tip credit, has unintentionally undermined the financial viability of full-service, labor-intensive restaurants. As costs outpace revenue and margins evaporate, once-thriving independent establishments are closing in droves, eroding the city’s cultural fabric and economic diversity.

Last fall, I celebrated my mom’s birthday at Fruition, which was once hailed as one of Denver’s best restaurants. By winter, its James Beard Award-winning chef and owner, Alex Seidel, had decided to close the establishment.

Mr. Seidel said that his decision came down to rising costs and policy changes that have made operating the restaurant unmanageable. He still operates two restaurants, one with three locations, in Denver. But when I asked if he would consider opening something new in the city, he replied, “Never.”

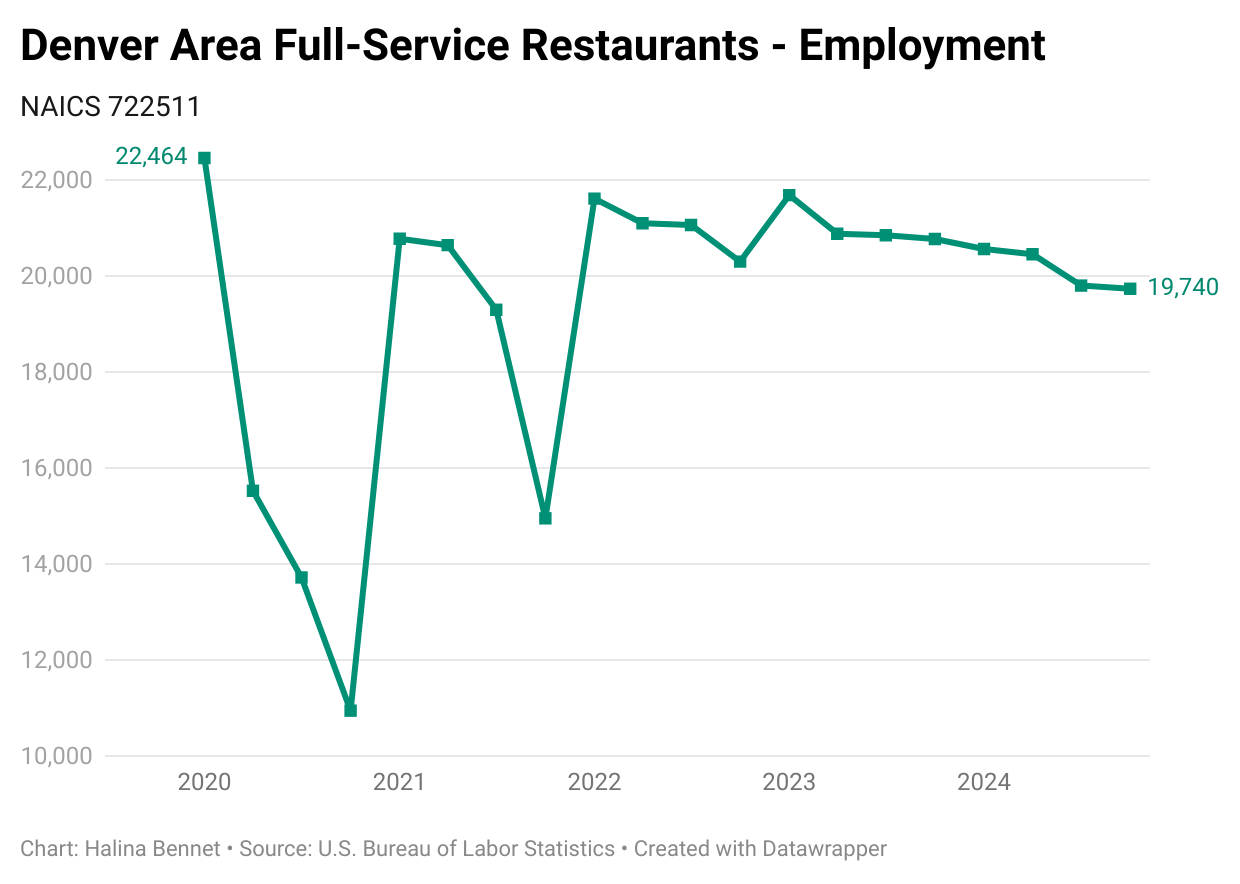

His was just one of the roughly 200 closures that the Bureau of Labor Statistics documented, reflecting an industry buckling under economic pressure.

The bureau also found that Denver currently faces a deficit of 2,700 full-service restaurant jobs.

A decade of decline

Delores Tronco co-founded her first restaurant, Work & Class, in Denver in 2014.

“I saw a restaurant industry that was on its way up,” Ms. Tronco said. “There were a lot of new openings and cool independent operators and chefs who were excited to build the cultural fabric of our city.”

She sold that business to her co-founder three years later to open a restaurant in New York City, which shuttered just 96 days after opening due to Covid. Ms. Tronco returned to Denver in September 2020 and launched her current venture, The Greenwich. She described the scene she left and the one she came back to as “night and day.”

“I came back to a place that has gradually, since 2021, seen the number of openings slow precipitously,” she added. “The openings that are happening are largely corporate.”

She noted that independent, mom-and-pop, and immigrant-run restaurants are consistently the most vulnerable.

“It's a net loss to our community when we lose small restaurants: the ones that are unique, the one that you want to go to for your birthday or your anniversary, or you know, the ones that tourists want to visit when they come to town,” Ms. Tronco said.

Her frustration is compounded by what she sees as misplaced priorities, noting that Denver paid $70,000 to $100,000 to Michelin in 2023 to be considered for its guide. That year, three Denver restaurants were awarded stars. With independent restaurants clearly acting as a boon to tourism and the city’s cultural cachet, Ms. Tronco said she doesn’t understand why the city’s investment did not motivate it to increase its support.

“Michelin doesn't want to give Matsuhisa a star,” she said, referring to Denver’s location of Chef Nobu Matsuhisa’s global restaurant group, which runs dozens of Nobu and Matsuhisa locations worldwide.

Rising costs and high wages

Restaurant operators and advocacy groups agree that Covid sparked the decline, but rising costs since have continued to cripple the industry. Property taxes, utilities, insurance, food and drink prices, rent, and one of the highest minimum wages in the country — higher than in Los Angeles or New York — are straining already razor-thin margins.

The city’s low tip credit, which results in a high minimum wage for tipped workers, is a particular pain point.

Denver City Council unanimously passed a minimum wage increase in November 2019 — just four months before the pandemic hit — and it was fully implemented citywide by 2022. Today, the base minimum wage is $18.81 an hour and the tipped wage is $15.79 — increases of about 70 percent and 95 percent, respectively.1

The city allows a $3.02 per hour tip credit, meaning employers can count that amount toward the standard wage. If an employee’s total earnings fall short, employers are legally required to cover the difference. That credit, until recent legislation passed, had remained static.

Per 2019 legislation, wage increases are uncapped and rise annually with the Consumer Price Index. In 2026, the base wage will be $19.29. For operators like Ms. Tronco and Mr. Seidel, who said that labor now consumes more than half his revenue, the math no longer works.

“When you force an operator to give raises every January 1 to the group of people who's already making the most money, it chokes our ability to give a salaried person or an hourly cook a raise,” Ms. Tronco said. “I’m working so hard to just keep it open, and try to make sure that my 34 employees stay employed, and that they get paid every week.”

Ms. Tronco said her servers are averaging $38 to $50 an hour — more than what she or her executive chef make when broken down hourly. She pays kitchen staff $23 to $25 per hour to stay competitive and said other operators and general managers are paying themselves minimal or no salaries at all.

To keep her business alive, Ms. Tronco has cut the hosts and bussers she hired when opening and reduced weeknight server shifts. She raises her menu prices every six months to keep up with costs. Her numbers have taken a hit: Sales are down an average of 10 percent this year.

“It just feels like whack-a-mole,” Ms. Tronco said. “Inflation has affected everyone … Now we’ve got a tariff situation and all my wine importers are telling me that everything is going to go up $3, $4 a bottle.”

Denver lacks the population density and affluent tourists of New York City, Los Angeles, or Washington, D.C. That makes it hard, Ms. Tronco explained, to charge the going Denver menu price of $38 to $42 for a half chicken, even when costs demand it.

“You raise the tipped wage, and I have to raise menu prices to cover it,” said Troy Guard, the owner and executive chef of TAG Restaurant Group.

Mr. Guard moved to Denver 25 years ago and, by 2020, was operating 18 restaurants. After relocating to Houston last year, he left twelve of his Denver locations in place, though he now plans to shutter up to four and is looking to exit the rest.

“I want nothing to do with it anymore,” Mr. Guard said. “I don’t live in Denver anymore. I don’t want to open in Denver anymore. It’s not my favorite place to do business. I have more opportunities in Houston.”

Houston ranked second nationally in population growth between 2023 and 2024, which Mr. Guard attributed to lower living costs. Despite its lower minimum wage,2 Mr. Guard said his employees can still afford to live near the city.

Isabella, a 27-year-old server in an independently owned Mexican restaurant, said that she takes home around $30 an hour on weekdays and $50 an hour on weekends between her wage and tips. Speaking on the condition that only her first name be used, she said that the wage increase means she no longer has to worry about whether to pay her bills or buy groceries during any given week. But still, her increased earnings barely keep up with rising expenses.

“I don’t know what the other option would be,” she said of the high tipped minimum wage. “It’s hard to live here, and even with the raises, I don’t feel like I’m walking away with more money.”

While she’s kept her job as restaurants make cuts, she said that many of her peers have not.

Eamon Nussbaum, 21, worked part-time over the summer as a delivery driver for a small, 40-year-old Chinese restaurant and as server at a Mexican restaurant that opened last year. Both are family-run.

The Mexican restaurant was so understaffed that Mr. Nussbaum often went beyond his server responsibilities and acted as a bartender, a busser, and was regularly in the kitchen making chips. He said that the single chef who cooks every meal once had a toothache and the restaurant had to close for dinner service.

Mr. Nussbaum, a student living with his parents, said that he did not face the financial pressure of many of his coworkers, but that it was clear to him how hard his employers were fighting to stay afloat.

“I think Denver is a much better place if they succeed,” he said.

House Bill 1208, signed into law in June, allows municipalities to expand the tip credit. In his signing statement, Governor Jared Polis called it an essential step in correcting “out-of-whack tipped wage minimums.”

Ms. Tronco, who testified for the bill, said the version that passed “gives us a tiny bit of protection from things getting worse, but it's not going to offer any immediate relief at all.”

“We’ve got to fix this before it’s too late,” Ms. Tronco continued. “We are just watching places drop.”

Scott Wasserman, a former labor union president and longtime advocate of minimum wage increases, said Denver must expand its tip credit.

“Restaurants hit a tipping point,” Mr. Wasserman said.

He acknowledged the arguments of organizations like One Fair Wage, which advocates eliminating the tipped wage in favor of a single, higher base wage for all. But in Denver, where the minimum will near $20 next year, “the math doesn’t work.” One Fair Wage did not respond to requests for comment.

Despite widespread support for minimum wage increases, the trade-offs are hard to ignore. As fixed costs like labor, rent, taxes, and ingredients rise, something has to give. Increasingly, what’s giving is the existence of the restaurant itself. As the businesses disappear across Colorado, so do the jobs that support 11 percent of the state’s workforce.

A systemic ripple effect

Juan Padró, founder of Culinary Creative Group, said closures don’t only impact restaurants — they hurt entire ecosystems. His restaurant Bar Dough uses 43 vendors, many local. But rising costs force him to consider cheaper, out-of-state alternatives.

“We’re destroying our farming communities. We’re destroying our ranching communities. We’re destroying craft beer,” he said.

Mr. Padró said the small tip credit is the industry’s biggest burden. He supports a higher base wage, even up to $25, because most of his employees already earn above that. He said that his servers and bartenders average $38 and $44, respectively. Expanding the tip credit would alleviate some of the burden faced by operators.

“I have 17-year-old kids pouring coffee for their teachers, making more than them,” he said.

Mr. Padró implemented a service charge model to pay all employees, including back-of-house, what he considers fairly. It allows him to avoid the legal limitations of tip-sharing despite taking on higher taxes.

“It's very important for me to take care of my most vulnerable, who are usually the cooks and the guys in the back of the restaurant,” Mr. Padró said. “I'm taking that hit from a business perspective so I can pay my most vulnerable.”

There are other operators who have found success with the model. Bill Taibe, owner of Japanese pub Kawa Ni, opened in Denver two years ago with a service charge model. He says it’s been a “smashing success.”

Having operated in expensive Fairfield County, Conn. for 15 years, Mr. Taibe came to Denver expecting high costs, so he brought creative solutions. He said that other operators who opened before the minimum wage hike have been playing an impossible game of catch-up, but he was able to establish a system of redistribution that ensures his employees earn as much or more than they would with tips alone.

“Denver has everything you’d want to be a great food city,” Mr. Taibe said. “The city just needs to take care of the people who are pouring their heart and soul into it.”

Restaurants in distress

Denise Mickelsen of the Colorado Restaurant Association (C.R.A.) said most operators are just trying to survive 2025. Though restaurants across the U.S. face similar challenges, she believes Colorado is the hardest place to operate one.

C.R.A. and USA Today reported that Colorado had the highest menu-price inflation in the country in 2023. One operator told her costs are up 39 percent since last year, while menu prices only rose 15 percent. Customers are falling away.

“She’s in the red,” Ms. Mickelsen said. “She has lost so much money in the last three years, she doesn’t know if they're going to make it through Christmas.”

Last month, Cap City Tavern, a Denver staple that Mayor Mike Johnston eulogized in his July State of the City address, closed. A note on its Instagram reads:

“The increase in minimum wage, cost of food, and the taxes and fees that the city of Denver is imposing on restaurants has become too much to bear. Sadly, we are not alone, as the community of independently owned restaurants in Denver is literally going extinct.”

Other longtime institutions are closing too. Zoe Ma Ma, in LoDo, shut down after losing its office-lunch crowd. El Noa Noa, a 45-year-old Mexican restaurant, closed in May. Ms. Mickelsen pointed to the Trump Administration’s immigration crackdown as another compounding factor in the widespread anxieties affecting the industry. She said that the fear of raids in restaurants across the state is crippling for employees.

“It is the neighborhood anchors and institutions that just cannot make it work,” Ms. Mickelsen said. “The places that have served their neighborhoods for decades, employed members of the community, made Denver home, are going.”

Due to regulatory limitations, data on closures is sparse. C.R.A. points to a 24 percent drop in active food licenses in Denver, though the auditor’s office questioned using that as a metric for industry health.

Even generous lease incentives can’t lure back top operators. Mr. Guard said that pre-Covid, landlords offered $50 to $100 per square foot to attract tenants. This year, he was offered $1,000.

“That's 90 percent more. That's how bad it is out there,” he said. “But the risk isn’t worth the reward.”

Denver has hired contractors to evaluate the industry’s concerns and develop a support plan. But it will take balance: supporting workers while ensuring restaurants survive. With legacy institutions disappearing, the city must also attract a new generation of restaurateurs.

“This business has always been tough, especially for the less famous, local family-operated places,” Mr. Guard said. “But when you have James Beard winners closing restaurants, that should tell you something.”

Texas follows the federal $7.25 minimum wage, which outlines a $2.13 minimum wage for tipped workers. The federal minimum wage has not risen since 2009, and legislation like the Raise the Wage Act are pushing for an increase to ensure a living wage for service workers across the country who do not live in (typically blue) states where labor advocacy is prioritized.

People tend not to realize how much a lot of waiters make and tipping has spread culturally rather than shrank as the tipped minimum wages have gone up.

The solution is just for prices to go up, tips to go away and restaurants to just operate like a normal business. It is hard for restaurants to raise prices when people are adding an extra 20% onto their own bill and the tipping culture is still very strong so it's hard to convince people that it is okay not to tip because you pay your waiters enough.

"Denver’s high minimum wage, especially its low tip credit, has unintentionally undermined the financial viability of full-service, labor-intensive restaurants. "

Entirely predictable. The single funniest line in the entire article is that new openings are mostly corporate, not mom and pop. Same result as when you introduce rent control. It' just baffling how that works every single time.