“Corporate power” doesn’t mean anything

You can’t fight what you can’t measure or define.

When trying to mobilize support for political action, people typically use language and slogans that are a bit vague.

If you say you want to achieve “racial justice,” for example, that raises the question of what specifically you mean. And even terminology that’s less ideologically freighted carries these definitional questions. If a member of the city council says she’s fighting for safer streets, that’s not exactly confusing. But people can and do disagree about exactly how to measure that: Should the city council use a broad index of reported crimes? Or focus on something better-measured, like homicides? But if murder declines in part because of better emergency medicine rather than fewer people getting shot, is that really what the council member meant by safer? A lot of people are interested in disorder broadly, but it’s hard to measure it or to distinguish between objective aspects of public order and potentially mediagenic phenomena where things seem safer or less safe.

It’s important to keep these measurement issues in mind, but a political project isn’t doomed just because there are questions about how to measure success.

People who are really serious about combating economic inequality ought to be aware that there are a bunch of things this might mean and also disagreements about the measures. But it’s not necessary for every single discussion about inequality to be deeply invested in the technical issues, and people can speak and write at varying levels of generality.

I do want to suggest, though, that when people say they want a political movement focused on fighting corporate power, they are dealing with fatal problems of precision and measurement.

What am I talking about? Well, some examples:

Anita Jain is the editorial director of the Open Markets Institute, which, according to her, is “a think tank that seeks to regulate Big Tech monopolies and curb corporate power.”

Katie Curran O’Malley ran a failed primary for Maryland attorney general in 2022, during which time she told the Washington Monthly, “we’re living in an era of extraordinary corporate power,” a line they liked enough to make the headline of their interview with her.

An October 2025 article co-produced by the Revolving Door Project and the American Prospect criticized the Trump administration’s Department of Health and Human Services with the line, “though MAHA may talk a tough game on corporate power, they ultimately recycle the same corrosive politics that hollow out public institutions while leaving corporate power untouched.”

These are the turns of phrase that some people — usually those affiliated with a specific cluster of institutions and/or politicians — use when they’re seeking praise from others associated with those institutions.

And I think the term works fine as a shibboleth. If a writer writes about taking on corporate power, that signals something about what they believe.

But while I may agree with the upshot of their analysis on a particular issue (and I definitely agree with the Revolving Door Project and the American Prospect that Trump’s approach to public health is bad), this is not an analytically fruitful framework for evaluating anything.

If we were in an age of extraordinary corporate power in 2022, has corporate power gone up since then? Did it decline during the Biden administration and then spike last year under Trump? What was the relevant index of corporate power in 2002 or 1972? These are not answerable questions. Not because it’s something like inequality where people argue over different ways to measure, but because there simply is no way to measure it at all. “Corporate power” is a concatenation of two abstractions that doesn’t add up to anything measurable or actionable.

Measuring things is important

One of Republicans’ best issues is crime. Voters have a strong predisposition in favor of toughness, and they believe Democrats have ambivalent feelings about harsh punishment.

But if you’re genuinely interested in reducing crime, it is worth reflecting on the fact that more liberal states tend to have lower crime.

If you point this out, a million Racist Twitter accounts will pop up with Steve Sailer memes and the observation that the red-blue crime gap is in part a function of demographics. In other words, the highest-crime states tend to be Southern states with conservative politics and large African-American populations, while the super-white red states of the Northern Plains have lower levels of crime. But although demographic factors account for a large fraction of the statistical variation in crime, they absolutely do not fully account for the red-blue crime gap. Race also can’t possibly explain why the highest-crime city in France has a murder rate lower than rural American states like Nebraska and Montana. Both gun laws and the enforcement of those laws are extremely important factors in explaining why New York and California have much lower murder rates than Texas and Florida.

Of course, there’s more to life than murder rates, and conservatives are entitled to their preferences.

My point is that cross-sectional data — both comparing American states to each other and also comparing America to other countries — is useful for structuring a discussion, and to have cross-sectional data we need to be able to agree on what we’re trying to measure.

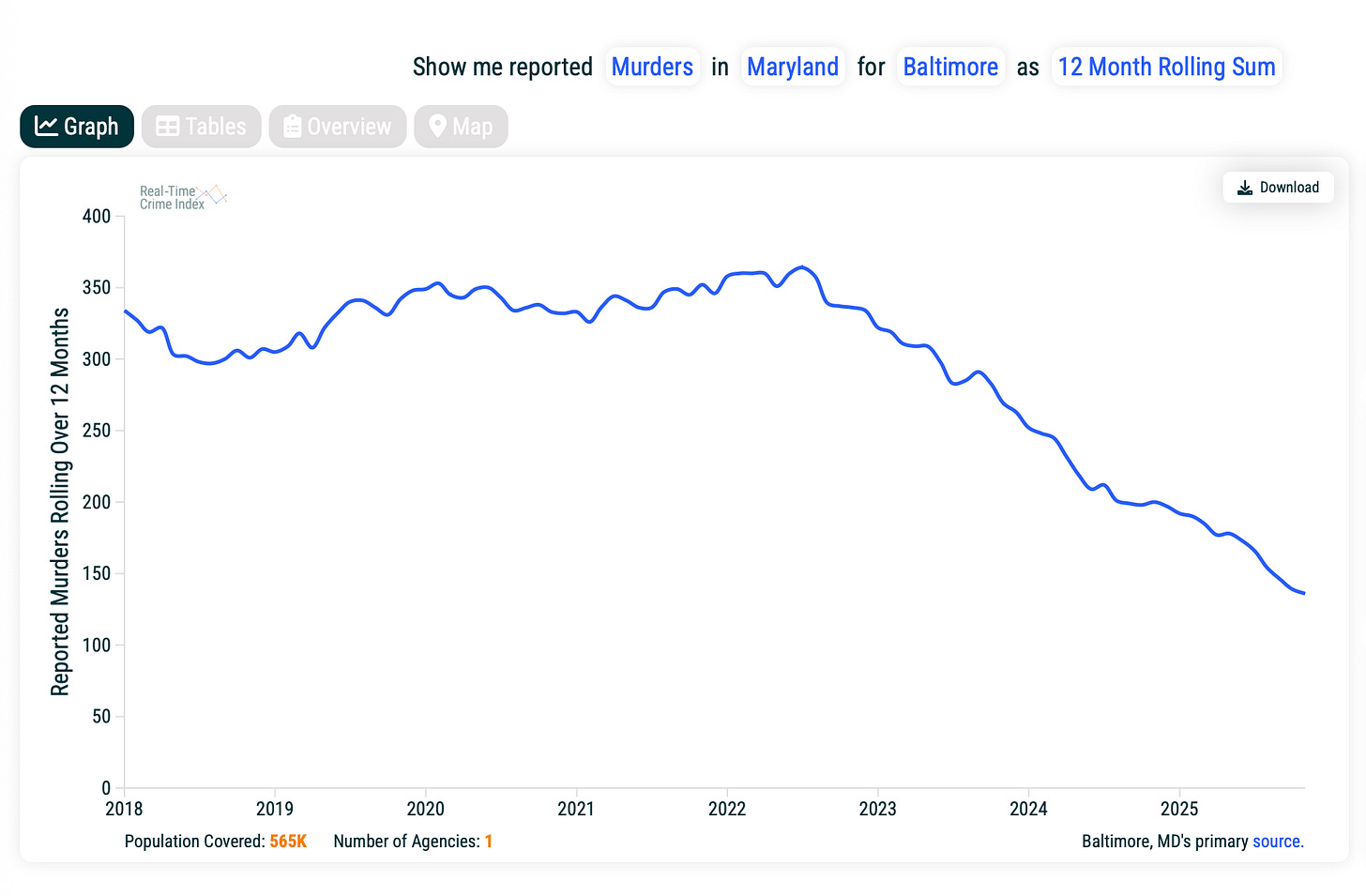

Time-series data is also important. Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott and Maryland Governor Wes Moore both have reason to be proud of the dramatic decline in murders that has occurred in Baltimore in recent years.

But you do want to temper your time-series analysis with your cross-sectional information. Baltimore is way safer than it was five years ago, but in absolute terms it’s still a high-crime city. So while the relevant public officials have good reason to be proud, you wouldn’t want them to be complacent. If you don’t measure, though, you could mess this stuff up. Casually glancing at Baltimore, it seems like a pretty troubled city. It’s only by tracking the trend that you can see they’re on a good course and need to stick with what’s working.

A different example, close to my heart: Part of the origin of the YIMBY movement is that back twenty years ago a bunch of different affordable housing organizations were pushing a bunch of different policy ideas. But if you looked at the observed variation in where housing was most and least affordable, it did not seem like the places that had implemented the recommendations of the affordable housing advocates were the places where it was easiest to afford a home.

It turns out that what these advocates were doing was advocating for the creation of housing units with a specific non-market regulatory status known as “affordable housing.” But the places where housing was most affordable were not places with lots of “affordable housing.” They were either places where demand was quite low, or places with a mix of cheap land and a relatively low regulatory burden to new supply. So the YIMBY idea is that instead of just maximizing “affordable housing,” we should be trying to lower the regulatory barriers to new supply since that is a major driver of affordability.

Measuring things matters, and it matters what you measure.

The “corporate” mirage

A notable aspect of the corporate power discourse is that its proponents don’t even try to produce either time-series or cross-sectional analysis.

If you want to talk about climate policy, you will almost immediately end up in a discussion about trends in emissions (America falling, India rising, China stable) versus levels of emissions (America high, China higher, India lower). But then people will debate whether it’s better to use per capita (in which case China is high but America is higher and India is super-low) or whether to look at the present day or the broad arc of history. When discussing taxes, people generally know that Nordic countries have high levels of tax and spending compared to the United States, and that, in the U.S., California and New York have high top income tax rates. There’s a whole set of facts people agree on, and there are facts that are known to be in dispute. But everyone is always ranking things.

When it comes to corporate power, though, the corporate power people themselves aren’t really making specific claims about relative levels of corporate power. Is there more in Oregon or in Michigan? Has corporate power gone up or down over time? We know that certain specific individuals are regarded as champions of fighting corporate power. But when they fight, do they win? How would we know? Is there corporate power in Denmark? There are certainly corporations in Denmark, and people work for them and buy their products — how else would it work?

I think part of the issue here is that “corporate” is a weird word. When I see someone refer to Starbucks as “corporate coffee” or a book titled “Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise and Fall of SST Records,” I do understand what they’re saying.

At the same time, the iconic indie label SST Records is, in fact, a corporation. So is your favorite neighborhood coffee shop.

What we’re talking about when we talk about corporate rock is an aesthetic. It’s an aesthetic that (before the ascent of the poptimists) was derided by its opponents as bland, as representing a business desire to be as broadly appealing as possible rather than tapping into real art or self-expression.

As a rhetorical trope, it’s similar to the idea of “slop.” But it doesn’t literally express an objection to record companies being incorporated.

Similarly, we kind of vaguely understand that by “corporate media,” people mean the big mainstream media companies. But your favorite small magazine or alt weekly newspaper was also a corporation. Opposition to “corporate coffee” was opposition to homogenization and the flattening of local difference, but one reason that particular rhetorical mode is heard less often these days is that the internet has generated a kind of aesthetic flattening even on independent businesses. I’ve been to independent coffee shops in Kerrville, Texas, and Deer Isle, Maine, that look like Instagram posts straight from Brooklyn or Echo Park.

But if you want to be factual, the whole economy — including the cool parts of it — is a bunch of corporations. The sloppiness of this rhetoric about what it means for something to be “corporate” is not a big problem for music criticism. But it makes it impossible to translate anti-corporate sentiment in any kind of usable public-policy analysis, since you can’t measure something that has no definition.

The limits of “fighting”

What people who want to see more emphasis on fighting corporate power do have is a list of figures they like, such as Elizabeth Warren and Lina Khan, who have a solid record of taking positions that are highly antagonistic to business leaders.

So while there isn’t an index of corporate power such that we can say which places have succeeded more or less than others at fighting it, there is a group of people with a disposition to wage political battles against business interests.

Here one thing I would note is that most furiously lobbied-over issues in a practical sense just pit businesses against each other. Pharmaceutical companies and pharmacy benefit managers both hire lobbyists and then the lobbyists fight each other. Credit card companies and retailers both hire lobbyists and fight in Congress about swipe fees. It’s important for political actors to try to decide who is right in these disputes, but whichever side you come down on you’ll find some corporate actors on your side.

You can maintain an anti-business affect as a political persona, but it’s not a useful guide to specific issues. And the lack of index in terms of policy outcomes here is relevant. There are backbench legislators who have this as the center of their political agenda, but you almost never see it in an incumbent executive officeholder. If Gavin Newsom or Gretchen Whitmer or Wes Moore or Maura Healey were overtly hostile to business, then major businesses would leave their states, which would be bad. This — capital flight — is the actual issue, not lobbying clout. Michigan wants Michigan-based businesses to succeed and it wants to attract inbound investment.

You might take Zohran Mamdani as illustrating the outer frontiers of what’s conceptually possible here. He’s a self-described democratic socialist who’s talking about cutting red tape for small businesses. He’s kind of spiritually aligned with the idea that Wall Street billionaires are bad, but he’s not trying to run the finance industry out of town.

None of this is to say that you can’t or shouldn’t regulate corporations. It’s just that there are basically two kinds of economies: one where businesses are growing and thriving, and one where there’s no growth and the economy is sputtering. It’s true that there are some communities that have a university campus or a military base as their main economic driver rather than a for-profit business. But these are edge case exceptions that prove the rule. A prosperous place is going to have prospering businesses — powerful corporations — that anchor the economy.

Looking for something else to read? For coverage of Trump’s war on birthright citizenship, see Halina Bennet’s post here.

Re: measuring stuff it turns out "how do you measure market power" can be the subject of a whole class which at Yale is numbered ECON 3385. Right now we are on week 3 and we are still working out how to estimate demand in multi-product markets.

Re: the broader point of the post, I agree that "corporate power" can be a vague term, but I think you could've engaged more with some of the evidence that market power has been increasing. For example here is a CEA brief from 2016 that we had to read for the first meeting of antitrust policy class: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20160414_cea_competition_issue_brief.pdf. It finds that firm entry rates are down, more and larger mergers are happening, etc etc. The brief itself notes that this is not slam-dunk evidence that concentration is for sure increasing across the economy, but it is suggestive that something may be happening.

C'mon, Matt. You've been around these people your *entire* life. Adept verbally, they use language to illuminate, advocate, describe, defend or obscure. If they are using some words that you cannot understand, that is by design.

They are anti-capitalists. Same as the communists in the 1930's, same as the campus radicals of the 1970s, now they are Democratic Socialists. They broadly believe their own morality is so superior, their ideas are so brilliant, their cause is so just that they should be in charge of making decisions about ... well, everything. And they believe making a profit is de facto proof of exploitation.

Let them be the critics. That's useful. Also, a market economy results in losers as well as winners, and these people can create systems and non-profits for making losing a bit less hurtful and catastrophic. That is a valuable and necessary role for a successful society. But we cannot let them actually run things. That would be bad.