A few weeks ago, David Dayen of the American Prospect published a weird screed against supply-side progressives in which he caricatured me as believing that “democracy — the ability for the public to express their views on matters that will affect them and get a hearing — isn’t worth the trouble.”

I thought the piece was top-to-bottom awful and sadly reflective of a collapse of intellectual rigor and honesty at the publication where I started my career. But I think that one particularly absurd line gets at the heart of this argument: is democracy about people expressing views at hearings or is it about entrusting elected leaders with the authority to make decisions on subjects of public concern? I think it’s the latter.

I decided a few years ago to put solar panels on my roof. Because I live in a historic district, I needed to get permission from the Historic Preservation Review Board. I was advised that such permission would be more likely to be granted if the proposal was endorsed by my local Advisory Neighborhood Committee. The solar installer and I couldn’t get ourselves on that month’s meeting agenda, and I had to be out of town on the evening of the following month’s meeting, but the month after that we schlepped over to a meeting and presented our plan. As it happens, none of the tiny handful of citizens who happen to have showed up that evening had any objection, so the ANC endorsed us and then the HPRB endorsed us at their next meeting, so the solar panels went forward with nothing more than three months’ delay and some wasted money.

I don’t think this meeting-ism is a very compelling example of democracy in action; a much better example is the D.C. Council eventually changing the rules to make it easier to install solar panels.

Elected officials should, of course, listen to people. But they should also decide what they want to do and make it happen. And we should not have state or federal laws that are designed to disempower elected officials. Unfortunately, though, we live in a world where the New York State Legislature can decide in 2019 that it wants congestion pricing for Manhattan and then spend three years compiling a 4,000+ page NEPA review.

What’s fascinating about this is that NEPA doesn’t even feature any substantive environmental standards. It’s a perfect example of what Nicholas Bagley calls “the procedure fetish,” a purely formal requirement that a lot of environmental impacts be thoroughly studied and thoroughly documented. Any action will make someone unhappy, and a big part of the post-1970 political order in the United States is that any governing decision is followed by a lot of lawsuits. So you do a lot of really arduous and time-consuming NEPA compliance so that you don’t lose in court. You do a lot of public hearings so that you don’t lose in court.

But why is it good to have courts review everything? Why would you consider hollowing out state capacity and undermining elected leaders “democracy?”

I think it’s a somewhat peculiarly American view, driven by the tremendous prestige the judicial system had heading into the 1970s thanks to their role in desegregation. But that judicialization of civil rights politics made sense because Jim Crow was, itself, undemocratic. The ultimate goal was civil equality, enfranchisement, and the creation of a democratic polity. And that should be our goal — a fair political system paired with a competent state and empowered leaders, not a morass of litigation.

What democracy looks like

If you’ve ever participated in progressive protest culture in the United States, you’ve probably heard people chanting “this is what democracy looks like!” and if you have a functioning analytic mind you’ve probably noticed that doesn’t make a ton of sense.

To me, “what democracy looks like” is the German federal election of 2017, which I witnessed in Berlin. A bunch of people showed up to orderly polling places with short-to-nonexistent lines where they filled out very brief ballots. Later, the votes were counted. A big, noisy crowd protesting isn’t a bad thing, but rather than seeing it as “what democracy looks like,” I think we ought to see it as a response to failures of democracy. The American Constitution embeds a fairly undemocratic set of institutional practices. It is quite possible that in 2024, Republicans could get 49% of the two-party vote and based on that, secure the White House and a bicameral majority in Congress. If that comes to pass, I think peaceful protest will become a crucial part of political resistance to a fundamentally illegitimate regime.

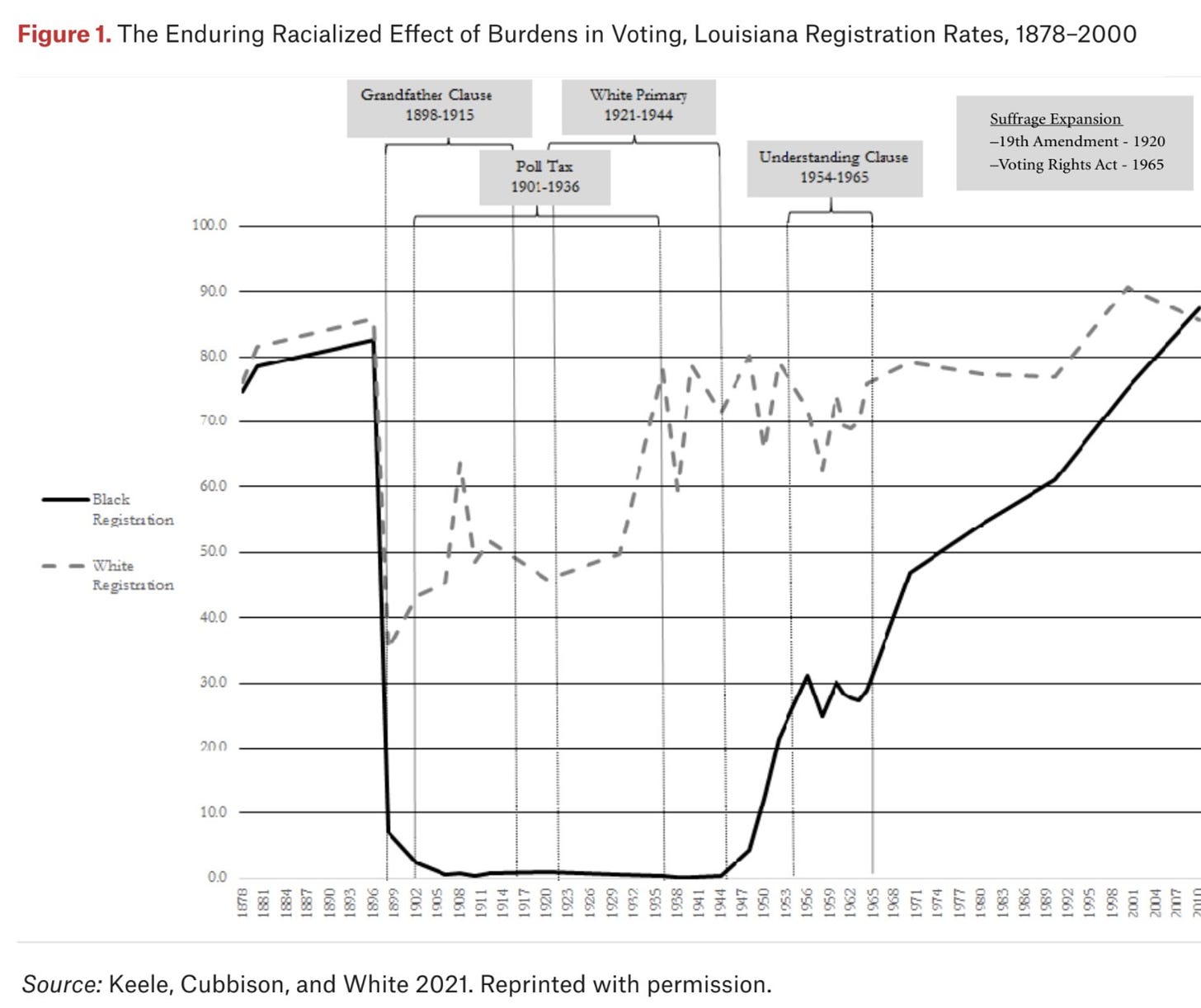

But part of what’s unusual about the United States is that not only do we have these peculiar institutional arrangements, but we also had a generations-long situation in which the large African American minority in the southern states was totally disenfranchised. Taking Louisiana as an example, we can see that Jim Crow had wide-ranging and long-lasting impacts on voter registration.

For about 40 years, Black registration was essentially zero.

Even after two registration surges associated with civil rights activity, Black registration only crossed 50% in the late-seventies.

White registration was also deeply depressed, especially during the poll tax era.

The registration gap only closed around 2010.

Even with full voting rights in place and the gap closed, over 10% of the eligible population isn’t registered to vote.

It’s not particularly unusual for a country to have had a non-democratic form of government in the first half of the 20th century. But what’s very unusual about the United States is that our civic culture had a strong perception of itself as democratic during the Jim Crow era. Franklin Roosevelt talked about the United States being the “arsenal of democracy” at a time when he was perfectly aware that democracy of the people, by the people, and for the people was excluding a very large number of people from participation.

I think the paradoxical circumstances of the mid-20th century left an odd dual legacy. On the one hand, there were largely successful efforts to democratize the formal political system. But on the other hand, there were efforts — also largely successful — to draw attention to the idea that “the community” might not have full control over the state and might need to be specifically empowered to check the state. But I think it’s more accurate to say that protest is what the lack of democracy looks like — people denied voice through the normal process demanding to be heard through extraordinary means. A certain romanticization of protest culture, though, has led to the idea that mass mobilization in the streets is somehow more authentically democratic than a functioning political system.

This era was also the high water mark of progressive jurisprudence and therefore progressive romance with litigation. A kind of superficial read of Brown v. Board of Education and the 20 years of civil rights litigation that preceded it might lead you to conclude that asking judges to intervene more could improve the outcomes of the political process. This was an accurate observation about the particular circumstances of the moment, but generalizing it is a big mistake.

The midcentury court situation was weird

The key thing about the heyday of civil rights litigation is that American political institutions were in a very peculiar place.

In the 1950 census, 10% of the American population was Black, with the largest share living in the states of the Old Confederacy, which meant many African American communities were completely shut out of the political process. But even though Little Rock’s Black citizens couldn’t effectively exert democratic political power, Black citizens could sue in federal courts and win cases. And even though Brown in 1954 is the famous one, civil rights plaintiffs scored a lot of wins over the years — going all the way back to a 1917 Supreme Court decision that disallowed explicit racial zoning. There was a 1941 case in which the lone Black member of the House of Representatives tried to book a first-class train car on a route that took him through the South. He was told that state law required segregation of train cars and that because there wasn’t much market demand for first-class tickets among Black customers, there was no designated car for Black first-class passengers.

He got the Supreme Court to rule that while “separate but equal” might be okay, that meant you actually did need to provide equal facilities, and if that wasn’t economically feasible, you had to back off of the separate part. That’s an eccentric edge case, but it set the stage for litigation demanding integration of graduate education, which eventually became the thin edge of a wedge to attack school segregation as a whole.

While this was playing out, with southern Blacks excluded from the political process, northern white politicians — Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, and John F. Kennedy — were all loosely supportive of civil rights. In particular, they generally appointed federal judges who were sympathetic to civil rights plaintiffs. But none of them wanted to pick big fights in Congress over civil rights, because they had other agenda items they wanted to collaborate with southern members on. The upshot was that the courts really could force the state to be much more responsive to the citizenry than the political process could. Thurgood Marshall and the other architects of this strategy were very smart people who correctly diagnosed a very strange situation, but overgeneralizing to the idea that “have lots of lawsuits” will in general improve outcomes is a mistake.

The ‘70s were a mistake

Talking to Ezra Klein about the need to streamline permission to build things, Gavin Newsom asked rhetorically “What the hell happened to the California of the ‘50s and ‘60s?”

The answer, of course, is that the ‘70s happened.

That decade saw a bunch of new social movements percolating in an era when civil rights had recently triumphed and when litigation had a lot of social prestige. It was understandable, albeit analytically mistaken, that people coming along in the immediate wake of those successes would implicitly and explicitly embrace the model of checking the state through the mechanisms of protest and litigation. You can even see why they might have adopted the belief that disempowering elected officials in favor of community consultation requirements was, in some sense, “more democratic.”

If you’re talking about a matter related to race in Georgia in 1973, then consulting with an ad hoc group of ministers and activists really might be an improvement on trusting a state apparatus that was shaped by Jim Crow.

But these considerations never really applied in the environmental context. Questions about pollution raise two kinds of issues: technical scientific questions about the impact of pollutants and democratic political questions about tradeoffs. Normal politics can get that kind of decision wrong for any number of reasons. But there’s no reason to think you can systematically improve on the outcome by getting more judges — who are neither technical subject matter experts nor accountable for outcomes — involved. With any given case, of course, you might succeed in stopping something bad or extracting a useful concession. But systematically, all that comes of requiring lots of review and consultation as a prelude to lots of litigation is that things happen more slowly. That’s good for extremely literal small-c conservative politics, but nobody — not conservatives and certainly not progressives — actually thinks “nothing should ever change” should be a lodestar for policy.

Give democracy a chance

I suppose you could rationalize the judicialization of environmental policy if you are genuinely skeptical that democracy will deliver the goods.

After all, the shellfish damaged by ocean acidification don’t get a vote. Nor do Nigerians living in 2123 who are subject to much more downside risk from climate change than Nebraskans living in 2023. If you can get people to agree, abstractly, that environmental impacts ought to be considered, then maybe you can get the courts to muscle the political system into considering factors that democratic politics would underweight.

But I think this line of thinking fails for a few reasons. One is that the whole civil rights litigation strategy really did depend on northern politicians appointing federal judges who were sympathetic to civil rights claims. There’s a kind of lawyerly myth that somehow “the Constitution” caused these good decisions to be handed down, but if elected officials had wanted to put pro-segregation judges on the bench, nothing about the text of the 14th Amendment would actually force them to make anti-segregation rulings. Congress, after all, originally passed a Civil Rights Act way back in 1875 only to see it struck down by the Supreme Court in 1883. It was a kind of happenstance of midcentury congressional politics that the judiciary was willing to address issues that Congress wouldn’t. The other is that as important as the work of Marshall and other civil rights litigators was, very little desegregation was actually achieved until the passage of civil rights and voting rights legislation in the mid-‘60s.

Something I’m always arguing with environmental groups about is that if you think a $50/ton carbon tax is politically infeasible, it’s not more feasible to achieve the same emissions reductions by blocking fossil fuel infrastructure to raise the cost of burning fossil fuels by $50/ton. People are going to notice if energy gets more expensive, and you will either be able to defend the tradeoff or not. It is probably more feasible to do it with taxes that minimize deadweight loss than with regulatory curbs.

Which is just to say that there are basically two levels on which you can’t really use judicial trickery to force the state to take environmental harms dramatically more seriously than the electorate. And while the electorate probably doesn’t take these things as seriously as they should — I wish voters cared more about the long-term and were more cosmopolitan — they do take them somewhat seriously and are willing to back policy changes that accomplish things. We have to trust ourselves to be able to win enough of the argument enough of the time to make the changes we want to see in the country, even knowing that sometimes democratic politics will make the wrong choice. The alternative is endless rounds of stagnation and litigation, arbitrarily advantaging the status quo and whoever has the best lawyers.

One cannot overemphasize the extent to which the civil rights era legitimized judicial review. For most of American history, judicial review was profoundly conservative. Federal courts issued hundreds of rulings voiding wage and hour laws and busting unions. In the depths of the great depression, they ruled that the National Recovery Act overstepped Congressional authority. Brown made normal Americans forget about how judges had acted for the past seventy years.

This century, the Supreme Court kept Florida from recounting votes, sealing a Republican presidential victory, ruled that rich people can spend as much as they like on political advocacy, and kept millions of poor people from getting Medicaid.

Now that Roe is gone, I hope progressives will see judicial review is generally at odds with effective governance.

Long time listener, first time caller. Great essay, as usual. One beef. This "illegitimate" language is incorrect and is analogous to Trumpers and "Stop the Steal" nonsense. Legitimacy in the US is determined by legality, full stop. In your scenario, if the elections were conducted legally, contested issues were resolved by courts, and so on, then the R majority "regime" would be in fact "legitimate" under the Constitution/laws of the US. That may be unfair, unrepresentative, morally wrong, whatever, but it would be legitimate.

"The American Constitution embeds a fairly undemocratic set of institutional practices. It is quite possible that in 2024, Republicans could get 49% of the two-party vote and based on that, secure the White House and a bicameral majority in Congress. If that comes to pass, I think peaceful protest will become a crucial part of political resistance to a fundamentally illegitimate regime."