Climate advocacy should focus more on the hard problems

We need technical solutions on steel, cement, agriculture, and more.

I argued yesterday that donor influence has put Democrats out of step with the concerns of working-class voters primarily by pushing them to adopt left-wing stands on cultural and environmental issues.

For the most part, I think the solution is pretty straightforward: The party should nominate and support candidates who are in line with public opinion in the states they’re running in, and party leaders should stand by this big tent strategy.

But climate change is the sticky wicket, because even though Democrats have a bad habit of siloing climate and energy policy away from economic policy, energy is an incredibly important aspect of “the economy.” You cannot have an economic policy agenda centered on advancing the economic interests of the working class and an energy agenda that totally ignores this. It would be politically convenient for Democrats — and healthy for American democracy — if every climate philanthropist woke up tomorrow and decided that what they actually care about is abortion rights at home and public health abroad.1

But, taking it as a given that people who are fired up about climate change will continue to be fired up about climate change, it would be constructive if they would engage with the topic more productively.

A huge share of climate funding in the United States is based on the false premise that there is a huge bank of “climate voters” who are themselves fired up about the issue and prepared to make meaningful sacrifices in order to address it. This is not true. In fact, I think it’s pretty obviously not true. But because there’s so much money available for climate activism, the field is full of stakeholders with personal investment in the status quo, and they expend incredible amounts of time and energy on trying to mislead others about this. So much so that it’s barely worth getting into the dirt and wrestling with them over the polling. Just consider that in a world where most voters cared about climate change, the following policy framework would make a ton of sense, politically:

Put a price on carbon equivalent to a credible estimate of the cost of carbon

Use some of the resulting revenue to cut other taxes

Use some of the resulting revenue to subsidize clean technology

There would, of course, be a lot of disagreement about the details, but that’s what the debate would be about: how high should the carbon price be, what non-carbon taxes should we cut, and how should we structure our clean spending. And 15 years ago, that’s what climate advocates were focused on. Their efforts at carbon pricing failed spectacularly, but instead of revisiting the premise that voters care a lot about this and are willing to make sacrifices to address it, the advocacy community keeps blocking infrastructure to make fossil fuels more expensive in a non-transparent way.

It’s far better to accept reality. Just because the voters don’t care about something doesn’t mean that you need to stop caring about it. But if your priorities diverge from those of the voters, you need to be smart. Which in the case of climate means much less emphasis on marginally speeding up the adoption of good climate solutions, and much more emphasis on trying to solve the remaining hard problems of climate change on a technical level.

Deep decarbonization is still not technically feasible

You can think of decarbonization as existing on a spectrum from things that have workable technical solutions to things where the only way to reduce emissions is to just give up on doing the thing.

At the easiest end of the spectrum right now, I would say, is using electric induction stoves for home cooking rather than natural gas. A majority of American stoves are already electric, the electric share is higher in other countries where energy costs are more salient, and the most widely recommended induction stoves are already cheaper than their gas competitors. A close cousin to electric cooking these days is the electric car, which is highly functional and just as good (if not better) for a majority of the driving that people do. One barrier to adoption is the logistics of taking a long road trip, but you can still definitely do a long road trip with an electric car. Another barrier is price, especially for the big trucks and S.U.V.s that Americans tend to prefer. On the other hand, the United States is deliberately keeping cheap Chinese E.V.s off the market. The barriers to adopting cheaper E.V.s are not all (or even primarily) technical.

At the other end of the spectrum is something like making cement.

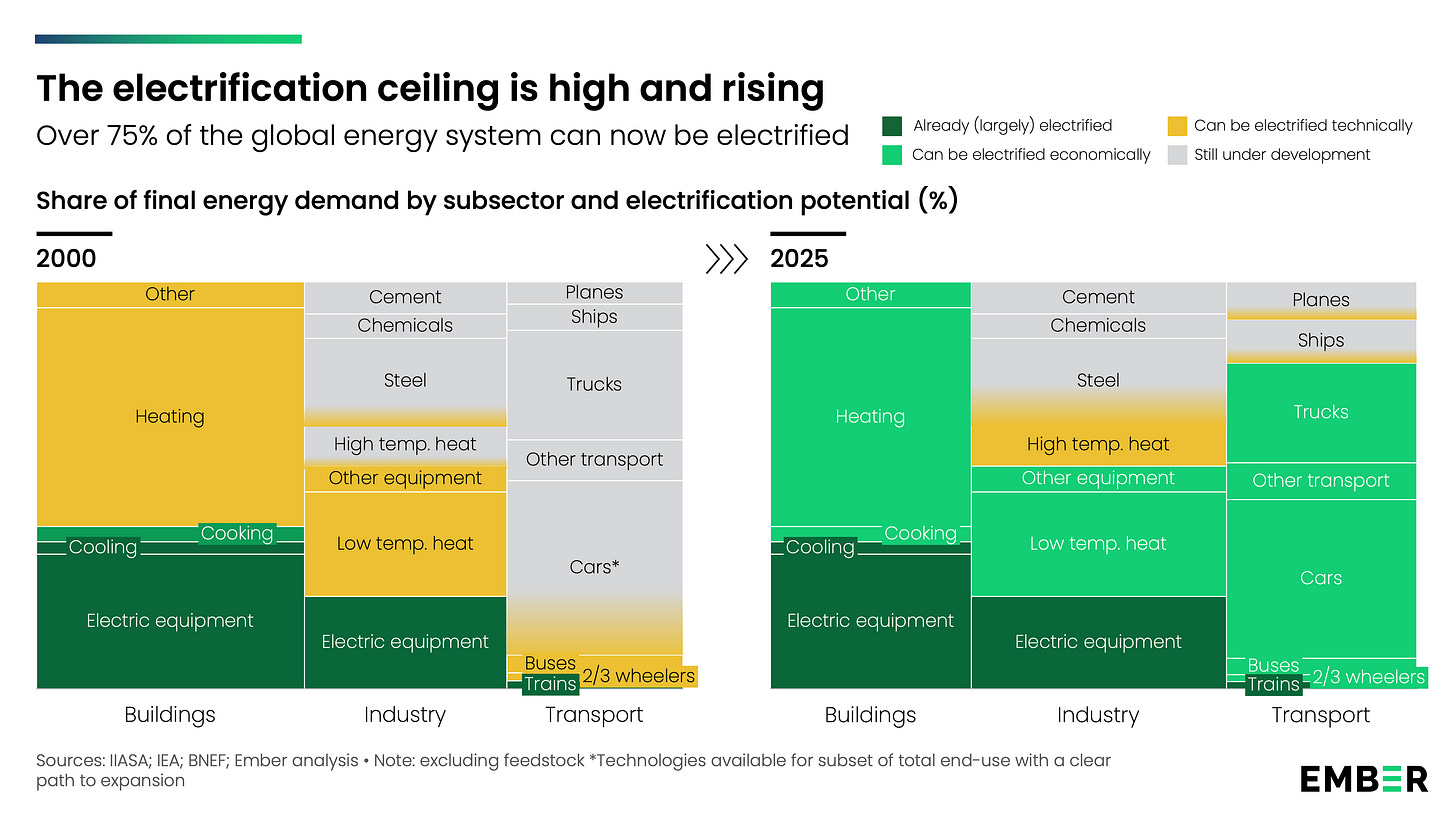

Interesting work is happening on trying to make low-carbon cement (David Roberts has a good interview with Leah Ellis on this topic) but it is not currently possible to scale. Similarly, it’s not feasible to use electricity to manufacture primary steel. This chart from Nicolas Fulghum I think tends to err on the side of optimism in classifying things like trucking as “can be electrified economically,” but I do think it illustrates the basic shape of the situation.

If I were making that chart, I would add a fifth category for things, like trucks, where today we can’t really do it economically but the roadmap is perfectly clear. We know how to build a good electric truck. The problem is that to make electric trucking cost effective, we need bigger and cheaper batteries. But batteries are getting bigger and cheaper, and the basic industrial processes and market forces that are working on this in an electric car context should carry over. Something like recreational boating is in a similar place — it’s not that the problem is solved, but the solution is within sight.

So I think there are two major takeaways from this chart:

One is that incredible progress has been made! It’s sometimes fashionable to declare that technology will not save us, but in fact, technological progress on decarbonization has been enormous, while progress on getting people to adopt degrowth solutions has been essentially zero.

The other is that there are a lot of problems that are either unsolved or at best semi-solved, where making more or faster technological progress would have a large impact on climate outcomes. Also note that while steel, chemicals, and cement add up to a smaller share of the world’s final energy demand than cars or heating, that’s not the only way to think of the significance of those sectors. The entire modern economy would completely collapse without steel, chemicals, and cement. So it’s not like these are trivial issues.

Advocacy is focused on the wrong end of the spectrum

Right now, a large share of climate advocacy and spending is focused on the topics that are at the “easy” end of the spectrum.

This would make sense in a counterfactual world in which the majority of voters care a lot about climate change and are willing to make meaningful material sacrifices to promote decarbonization. In that world, there’s still nothing we can do about the fact that some problems are technically hard. The very small gray “chemicals” box in the chart above, for example, contains within it the Haber-Bosch process for synthesizing ammonia. Without that process, global agricultural production would crash and we’d see mass starvation. In a universe of climate voters, you just leave ammonia alone and focus on banning gas stoves and internal-combustion-engine cars. Not only would that promote short-term emissions reduction, it would drive investment all throughout the stack. A ban on gas stoves or conventional cars would serve as a proof point that if someone, for example, did invent a zero-carbon boat, the government would act swiftly to make their competition illegal, which would make that type of invention a very promising avenue for investment.

But we are not in that world.

Banning normal consumer appliances is a political liability: vulnerable Democrats worry about taking these votes and vulnerable Republicans never cross the aisle to join with Democrats.

Instead, renewable energy, electric cars, heat pumps, and induction stoves are all growing primarily because the technology is good enough to be compelling to consumers. That’s not to say public policy, philanthropy, and advocacy had nothing to do with it. But these things all had the biggest impact when they drove the technology forward when it was in a more primitive state. And by the same token, the most important thing to do today is to put resources into trying to make technical progress on the issues where little has been made.

Innovation is hard, and hard to predict.

Maybe someone will come up with a viable method of using electricity to generate the kind of very high heat that you need for some of these applications. Maybe some kind of battery breakthrough will make electric passenger jets viable. Or maybe the answer will be something more like what Terraform Industries is doing, trying to manufacture hydrocarbons out of a mix of air and electricity.2 If that becomes cost-effective, then we don’t need to solve electrification problems in some of these other areas. Or maybe we could replace fossil fuels in some of these processes with pure hydrogen, which in principle can be manufactured out of water, if electricity is cheap enough.

Clean energy abundance

This last point about the cost of electricity is important.

To an extent, the case for switching from fossil fuel heat to heat pumps hinges on the performance characteristics of heat pumps. But it’s also a function of the price of electricity. This is probably less of a concern for those considering a switch to an electric car, but it’s still relevant. And of course, if everyone did switch to an electric car, that would drive up the price of electricity. And there are a lot of potential technological solutions related to things like green hydrogen or carbon capture that would only work if electricity were dramatically cheaper. By the same token, we could address a lot of the challenging climate issues at the nexus of agriculture and deforestation by switching to vertical farms — except that requires a ton of electricity.

All of which is to say that policy measures to dramatically increase the supply of clean energy are a big win.

A lot of conventional approaches seem to make the mistake of starting with current levels of energy use and then reasoning backward to figure out how much clean energy we “need.” But in the future, it would be desirable to use a lot more energy — in part so that poor people around the world can enjoy better living standards, in part so that we in the United States can enjoy better living standards, and in part so that we can deploy abundant electricity to solve some of these other problems by doing “wasteful” things like manufacturing synthetic hydrocarbons.

One virtue of a strong policy focus on this is that even if you are focused on clean energy abundance because you care a lot about climate change, you’re not asking other people to accept material sacrifice for the sake of climate. If clean electricity gets cheaper, people will just use it and, at that point, facilitating the deployment of clean energy is just solid pro-growth economic policy.

Most major environmental organizations in the United States, as well as prominent activists like Bill McKibben, think they have embraced this vision. Solar panels are really cheap, batteries are getting cheaper, and they’re enthusiastic about the idea that this means the renewable energy future will be cheap. Which is great.

But if you scratch the surface, they’re still obsessed with blocking fossil fuel production, even though if you ask them about carbon pricing, they’re happy to admit that making oil and gas expensive is a political dead end. There’s a lot of interest in the cutesy argument that blocking liquified natural gas exports will depress the domestic price of gas, so their anti-supply position is also good for reducing the cost of living. Or else they want to play Whac-A-Mole and block new sources of energy demand, like data centers, and say that’s a solution to cost of living problems.

This is clever as debate gamesmanship at a time of acute concern about prices, but it evades the actual issue. There are ideas that are clean and pro-growth (de-regulation of clean energy), and there are ideas that are clean and anti-growth (squelching energy demand or fossil fuel production). Clean anti-growth is fine, if you believe that people are eager to make substantial sacrifices for the sake of climate change. But again, that’s not true, and if it were true, we’d be talking about carbon pricing.

Taking the problem seriously

I understand that people who are passionate about climate change don’t like to hear this. But it is genuinely okay to be a high-minded person who cares about things like coastal flooding in Bangladesh in the 2060s, even if most voters don’t. If you really, truly, deeply care about an issue, though, you owe it to yourself to look reality squarely in the face.

And my point here is that “approaching climate change realistically” does not mean “giving up.”

It means refocusing our efforts on the things that have paid dividends in the past — trying to solve the hard technical barriers to decarbonization and trying to facilitate the deployment of zero-carbon energy. Singularly focusing on these two pillars will probably not achieve global net zero by 2050, but neither will banging our collective heads against the wall and ceding every election to Republicans.

Finally, I want to say that the last refuge of scoundrels on this topic is for advocates to hide behind their non-partisan non-electoral 501(c)3 status and say it’s not their job to worry about politics.

I’m sorry, but no.

I’m not asking you to break the law and do electoral work with tax exempt funding. But we all need to act like adults here. If you’re cooking up a policy and advocacy agenda, you have to pay attention to what’s plausible. If we’re sitting around a seminar table, I could make an argument to “cut Medicare and use the money to finance anti-malaria programs in Africa,” but that would be a ridiculous thing for an aid advocacy organization to spend its time talking about. It’s not going to happen, and if you succeed in branding “pay for it by cutting Medicare” as the authentic way for people who are passionate about global public health to engage with the issue, you’re going to engender catastrophic backlash.

There are many unmet needs on both the technical and the deployment side of these problems, plenty of things that could be worth funding, and lots of non-activism work that people could be doing. Go invent a better battery, build an electric boat, start a business installing heat pumps, develop a policy agenda for industrial decarbonization or efficient intensive agriculture, or try to find a way to stop conservatives from banning lab-grown proteins. Climate is a big problem! It’s great that a lot of people with resources at their disposal want to do something about it, but there’s a dire need to do things that are constructive rather than destructive.

Climate change is an important issue that impacts the lives of hundreds of millions of people around the world. But the current neglect of public health issues in poor countries is also tragic, and tons of people around the world are impacted by things like vitamin A deficiency and malaria.

The idea here is essentially to capture carbon dioxide and turn it into fossil fuels. Then when you burn the fuels, carbon goes back into the atmosphere. But instead of building up and causing a greenhouse effect, it gets captured again and recycles into fuel.

You allude to this, but it deserves a headline: another advantage of technical developments is that we can export them to places our policies and controls do not reach.

If every US citizen accepted Bill McKibben's or Kōhei Saitō’s vision tomorrow, that would, on its own, only 𝘥𝘦𝘭𝘢𝘺 global warming.

Speaking of investing in technology, if direct air capture of CO2 becomes efficient, cheap, and widespread enough, it is plausible to remove CO2 from the atmosphere on net, and actually begin cooling the atmosphere. But no one in the climate advocacy space seems interested in doing that.