Cash transfers work

Why we support GiveDirectly and hope you will, too

This Giving Tuesday, we’re working with Jill Filipovic and Judd Legum’s Popular Information to raise money for GiveDirectly, an organization that provides direct cash transfers to some of the people who need it most.

Can you help us raise $75,000?

If we meet our goal, GiveDirectly will be able to deliver $1,100 — a life-changing amount — to each of the 87 families in the rural Rwandan village of Nyarutovu. The post below talks more about GiveDirectly, and why we hope you’ll join us in supporting their work today.

If you’d like to make a donation, you can do so here. Slow Boring will match the first $5,000 from our readers.

Giving Tuesday has been around for a little over 10 years, and according to the official website “whether it’s making someone smile, helping a neighbor or stranger out, showing up for an issue or people we care about, or giving some of what we have to those who need our help, every act of generosity counts and everyone has something to contribute toward building the better world we all want to live in.”

That’s a nice idea! But it wouldn’t be Slow Boring if I didn’t encourage everyone to be a little more analytical with their time, money, and effort.

After all, “showing up for an issue” you care about isn’t a good idea if your actions backfire catastrophically. It’s also possible that the issue you care about is bad on the merits. Matt Damon, Mark Ruffalo and others who are trying to prevent a church in Manhattan from being redeveloped probably think they’re doing the right thing, but they are, in fact, making New York City worse off.1

Supporting causes that actually make the world better — not just those that make you feel better — is important.

I frequently tout the work of GiveWell, which I believe does the best job of sifting through the available data to find the optimal use of charitable funds. But I do think there’s something to the critique of charity as kind of a power move by people with money.

Research is imperfect and hinges in part on judgments about values. And realistically, any recommendations that I make reflect my judgments about the actual quality of the research, as well as those of the people I have confidence in, like the staff at GiveWell. I like to think that my judgments about these things are good, but I’m not immune to bias. Not everyone is willing to trust me to tell them what to do with their money, and that’s fair enough.

But that’s what’s so powerful about GiveDirectly.

GiveDirectly operates on the simple premise that when the richest people in the world give cash to the poorest people in the world, everyone can accomplish an incredible amount of good.

Opting for direct cash transfers minimizes both the aura and the reality of paternalism and acknowledges in a radical way the contingency of your own good fortune. Almost everyone who’s achieved any degree of success in life has done so in part thanks to their own talents and efforts. But we’ve also all benefitted in profound ways from luck — and one of the biggest strokes of luck a person can have is not being born into subsistence farming in a desperately poor country. Some barriers are just too profound to traverse, and an utter lack of economic opportunities remains a dire problem in too many parts of the world.

There is, essentially, one major analytic question one could ask about cash transfers: Is it possible that they actually leave recipients worse off?

The evidence overwhelmingly indicates that they do not. And given this basic fact — that cash transfers to the poorest people in the world makes them unquestionably better off — I think any number of political or ethical frameworks support the idea that you should do it. You don’t need to be convinced of much to be convinced that this is a good idea.

How GiveDirectly’s poverty relief program works

GiveDirectly runs a few different programs, all of which are built around direct transfers. But today I want to talk about what I think of as their most basic work, what they characterize as their “poverty relief” program. Through this program, GiveDirectly identifies low-income rural villages in low-income countries that have the financial infrastructure to support cash transfers, and they give each family in those villages $1,100.

There’s a lot of foreign aid money and poverty-focused philanthropy out there, and very little of it takes the form of cash transfers. That’s not because we have incredibly convincing evidence that non-cash programs are better than cash, but at least in part because, historically, we had no good way to deliver cash transfers to low-income rural areas. Spending money on things like infrastructure projects or hiring doctors to treat people was more logistically tractable than putting money into people’s hands. But the rise of cell phones has enabled mobile payments systems in many countries around the world, including some countries that are incredibly poor and otherwise lack well-developed banking systems.

This technology is not available everywhere. But quite a few places do meet these basic criteria, and GiveDirectly is now running poverty alleviation programs in Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Rwanda, and Uganda, plus other cash transfer programs in DR Congo, Nigeria, Morocco, Mozambique, and Togo.

GiveDirectly gives money to the entire village to prevent the transfers from becoming a source of ill will and contention, so they try to find a village where most or all residents are living on less than $2.15 per day — there are, sadly, enough such communities that the organization is not in imminent danger of running out of opportunities. In the villages, GiveDirectly staff use a combination of community meetings and door-to-door visits to explain the program and enroll participants, all of whom then receive $1,100 in mobile money. Why $1,100? It’s a little bit arbitrary, but that’s approximately the average annual expenditure for a household living in extreme poverty. It’s also a nice round number that’s easy to explain to donors. And it’s an amount that’s been studied before, so they can speak confidently about their programs, and I can speak confidently about them to you.

Giving people money works

Cash transfer programs have two notable (and appealing) qualities:

They’re pretty straightforward to study in a way that clearly demonstrates their impacts. It’s conceivable that a person could react to a cash windfall with some mix of unhealthy behaviors (blowing it on booze) or short-sightedness (working less), either of which could leave them worse off in the longer-term. But researchers have been able to conduct many studies on whether and how they actually help.

They’re relatively easy to scale. The landscape is littered with efforts to improve education or job training that work well in small settings with highly motivated instructors but that fail at larger scale. Cash transfers, by contrast, can just be done in more villages if more money is available and if we are confident that giving people money works.

And I think we should be pretty confident that it does. Francesca Bastagli, Jessica Hagen-Zanker, and Georgina Sturge did a meta-analysis of studies, and while there are plenty of null results across at least some dimension of outcomes, there are very few negative ones.

It’s too bad that studies have failed to find benefits to education, employment, and health. I’d like to be able to say that every single study concludes that access to a cash windfall makes people healthier and better educated in a way that raises employment and generates a positive flywheel of development. And there certainly are some studies that find that, but the honest truth is that money isn’t magic.

The good news, though, is that even on employment, there are very few studies showing a negative effect.

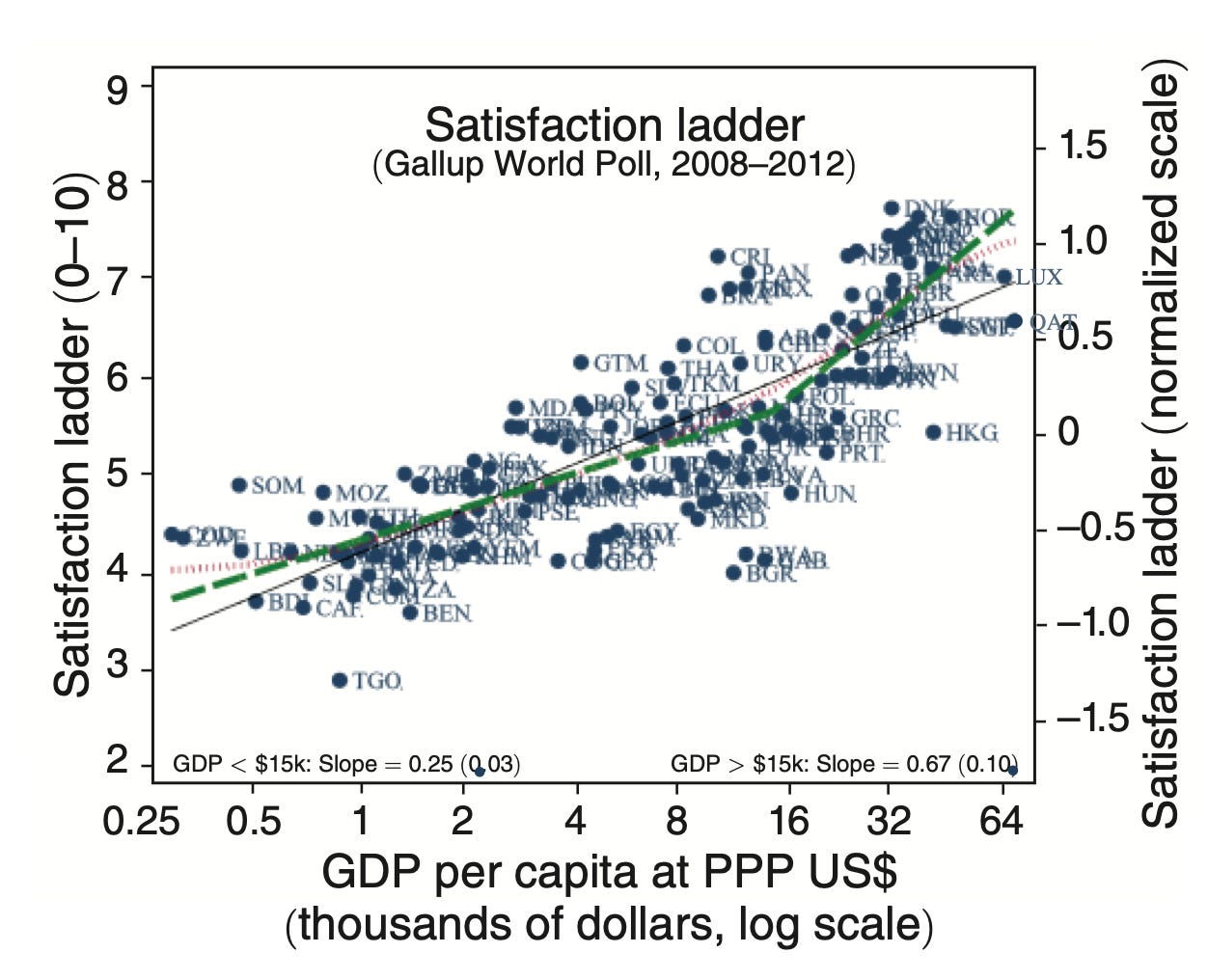

Families who receive money from GiveDirectly enjoy a short-term boost in their well-being, and there’s a decent chance they will also secure long-term benefits on at least some of these other dimensions. That’s really good! And I think it’s easy to underestimate exactly how big of a deal the basic financial boost can be in terms of subjective welfare. There’s a view that money doesn’t buy happiness, but Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers (and others who’ve looked at it) find that it pretty clearly does. But it’s possible to miss the impact because happiness scales with the log of income.

This means that redistribution is extremely powerful. If you are a single person with a post-tax income of $60,000 a year, you are richer than 99 percent of the world’s population. And if $1,000 flows out of your pocket and into the pocket of someone living on less than $1,000 a year, it is going to generate dramatically more subjective well-being for the person receiving the money than it costs you. It’s easy to get caught up in the concern that other people have more money than you (some of them certainly do), and to forget just how many have much, much less.

Giving people money is easy

For those of us who are privileged to live in the richest societies in human history, I think it’s important to know that meaningfully improving someone’s life is actually really easy.

You can literally just click on a link and send money to someone who really needs it and have very high confidence that they, and their neighbors, will be better off as a result.

You don’t need to puzzle through complicated optimization problems, you don’t need to figure out how to solve all the world’s problems, and you don’t need to spend your time doomscrolling and virtue signaling. If you would like to spend all your non-work hours just hanging out and having fun, and just click a link once a year to send a decent sum of money abroad, you are probably doing a lot on net to make the world a better place.

As I continue my descent into middle age, it really bugs me how dedicated so much of the media is to making people feel bad and how much social media seems to encourage wallowing in our own miseries.

Of course, we’re all allowed to focus on ourselves when we need to, and if you’re dealing with a lot right now, I’m not here to try to guilt you into thinking about the problems of poor people in Rwanda instead. But a lot of downer media content is geared toward making you feel bad about the state of the world, usually by encouraging you to fixate on alarming trends you can’t do anything about. GiveDirectly is, I think, a really liberating contrast: If you want to help some people, you can help some people. If you don’t, you don’t.

But I think most of us do want to feel like we’re contributing to solving the world’s problems, which is why that doomer content can be compelling. So go do something useful! Give money to people who don’t have very much! It has truly never been easier, and Slow Boring will even match the first $5,000 donated by our readers.

I am available to talk this issue through with any celebrities who want to give me a call.

Wow, y'all did quick work this morning! We just made our matching contribution. Thanks so much for your help!

Thanks to everyone who helped us blow past not just our initial goal of $75,000, but our stretch goal of $110,000 in less than one day! The campaign will stay open for a week, and we'd love to raise as much as possible. But GiveDirectly still has significant matching funds on the table for their main Giving Tuesday campaign, so we've updated our page with an option to give there instead before midnight tonight: https://www.givedirectly.org/slowboring/