Can new data solve an immigration puzzle?

No, but it does tell us a lot about immigration to the US, and about the challenges of measuring it.

Today we have a guest post from Jed Kolko, an economist who recently completed two years of service as the Under Secretary for Economic Affairs in the Department of Commerce, where he oversaw the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Economic Analysis. He was previously chief economist at Indeed and Trulia.

Immigration has long been among the most contentious topics in US politics. And this year, the data nerds have joined the fight.

In late 2023 and early 2024, government agencies released wildly different estimates of 2023 net immigration: 1.1 million people, said the Census Bureau, and 3.3 million, said the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). This huge gap caused economists to scramble to reinterpret existing data and create new alternative forecasts, and that matters for the most important economic policies: for example, the Fed adjusted its view of the labor market based on higher CBO immigration estimates.

Today, Census released annual survey data that are the key input into its immigration estimates:

These new data will probably lead Census to revise its 2023 immigration estimate upward by 300,000 people. That closes only a bit of the gap with CBO, though, so the data fights will continue.

The data also provide the first glimpse at who recent immigrants are and where in the US they live.

Finally, this entire debate over measuring immigration highlights many of the features and bugs of government statistics, and the challenges that data users and the statistical agencies face.

But before we get to the new numbers, it’s important to understand how immigration is estimated and why these estimates matter so much for getting an accurate read on the economy and setting economic policy.

Why are there multiple immigration estimates, and how could they be so far apart?

Numerous government agencies estimate the population. Annual Census population estimates guide the allocation of federal spending and also serve as the “population controls” for essential demographic surveys. (This turns out to be a big deal. More on this, below.) These annual estimates help bridge the gap between full-count decennial censuses, and they are revised to reflect new information each year. Other agencies produce population estimates and projections for their own purposes — CBO estimates and forecasts the population as inputs into their outlook for federal spending, revenue, and deficits.

Immigration is an essential part of estimating the size and growth of the population, and the trickiest.

Different agencies take different approaches to estimating immigration. Census immigration estimates are based primarily on its own survey data. The Census Bureau asks respondents about birthplace, citizenship, and residence one year ago in two key surveys: the large, annual American Community Survey (ACS) — whose 2023 data came out today — and the smaller, monthly Current Population Survey (CPS), which tracks the unemployment rate and other key labor market measures and is co-sponsored by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).1

The critical input into the Census immigration estimate is ACS data on foreign-born residents who lived abroad one year ago. Importantly, Census uses lagged survey data in its estimate. The 2023 population estimate was published in December 2023, incorporating 2022 ACS data released in September 2023. The 2023 ACS data released this morning will in turn be the basis for the immigration component of Census’s 2024 population estimate, due out in December 2024; Census will also revise its 2023 population estimate then, including the immigration component. In periods when immigration patterns change quickly, including during and after the pandemic, using lagged data can be more problematic.

In contrast, CBO immigration estimates incorporate administrative data alongside survey data. Administrative data track immigration-related actions, such as applications, visa issuances, and border encounters, which include apprehensions and expulsions. Widely reported Customs and Border Protection data showed a spike in border encounters in 2022 and 2023 and a drop in 2024. For its estimates, CBO uses survey data from the CPS, which is more recent but has a much smaller sample size than the ACS, and border-encounter data from Customs and Border Protection.

These different methods led to a huge divergence between Census and CBO immigration estimates in 2022 and 2023, as well as in their projections for 2024.

What accounts for this huge gap? Census’s use of lagged ACS data from 2022 probably made its 2023 estimate too low, though today’s release of ACS 2023 data might lead to only a modest upward revision in the 2023 estimate, as I’ll explain below. Also, Census 2023 estimates are for the year ending June 30, whereas CBO uses the calendar year, so Census 2023 estimates don’t include a possible spike in the second half of 2023; however, if you compare Census 2023 estimates to the average of CBO’s 2022 and 2023 estimates, there’s still a huge gap.

There are deeper reasons. Survey and administrative data have different purposes, strengths, and limitations, and they often disagree. Surveys might undercount immigrants, especially recent immigrants, and especially if they live in temporary or short-term housing. In contrast, administrative data could overstate migration if the same migrant is encountered at the border multiple times.2

How have economists coped?

Economists need an accurate view of immigration because immigrants are part of the workforce — or in econspeak, the labor supply. When labor demand runs ahead of labor supply, firms compete harder for workers and bid up wages, and the economy risks “overheating” with higher inflation. When labor demand falls short, the labor market softens, unemployment rises, and the economy risks sliding into recession. Maintaining the right balance between labor demand and labor supply starts with a clear view on labor supply. With an aging population, the native-born workforce grows slowly but predictably. Immigration is the wildcard for estimating and forecasting labor supply.

The Census immigration estimate may be too low, but it is baked into key data points. The Current Population Survey — also known as the household survey in the monthly jobs report — is “controlled” to the Census population estimates, which means that the weights assigned to each of the 100,000-ish individuals in the monthly survey add up to equal the national population estimate.3 If the CPS is controlled to a population estimate that includes an immigration estimate assumed to be too low, then ALL the levels and even some changes in levels that are generated from the CPS — including for native-born workers! — could be too low.4

To cope, economists have used higher immigration estimates than Census’s to recalculate data points that are controlled to Census population estimates. They have also paid close attention to data sources that are not controlled to Census population estimates and therefore might more fully incorporate an immigration surge, like the establishment survey in the monthly jobs report that asks businesses how many workers they have on payroll.

For instance, Hamilton Project researchers incorporated CBO’s higher assumptions in estimating the contribution of immigration to employment growth, consumer spending, and GDP. The Goldman Sachs research team has used an estimate closer to CBO’s than Census’s. And the Fed has used higher immigration assumptions in its own estimates of the size of the labor force than the baseline estimates that incorporate Census’s lower immigration numbers. If the Fed is paying attention, you know it’s not just an academic issue.

Here's how this plays out. Immigration makes the labor supply grow faster, increasing how many jobs need to be created in order to keep labor supply and labor demand in balance. The Hamilton Project paper estimates that the level of job creation today that would keep pace with the labor supply is around 160-200 thousand jobs under CBO immigration assumptions, versus a range of 60-100 thousand underlower Census immigration assumptions. Therefore, when the economy added 142,000 jobs in August, that either means the economy added too many jobs relative to labor supply growth and risks overheating, if Census immigration estimates are right, or the economy added too few jobs and is weakening, if CBO immigration estimates are right. And that’s why the Fed cares: they are more inclined toward rate cuts if it looks like the labor market is weakening than if it’s overheating.

Getting immigration estimates right matters for projecting government finances, too, since immigrants spend money, pay taxes, and use public services. Higher immigration levels would boost GDP and reduce the federal budget deficit. Furthermore, if the true level of immigration is higher than the Census estimate and closer to the CBO figure, some other economic data puzzles start to make more sense. For instance, higher actual immigration might explain the faster employment growth reported in the monthly establishment survey than in the household survey.

But what if economists have gone too far in assuming higher immigration than the Census estimate? A wide gap between estimates calls for lots of uncertainty and, ideally, humility. After last Friday’s jobs report, economist Julia Coronado quipped “I don't know who needs to hear this but you can't use immigration to explain everything you don't understand in the data.”

And that’s the cue for today’s new Census survey data. You’ve waited long enough.

At last! What do we learn from the new Census data?

The brand-new 2023 American Community Survey reports that the number of foreign-born U.S. residents who lived abroad one year ago was just under 1.7 million in 2023, the highest level since at least 2010 and an increase from 1.4 million in 2022.

Another way to look at net international migration is the change in the foreign-born population year-to-year. The ACS reported that the foreign-born population in 2023 was 47.8 million, an increase of 1.6 million from the 2022 level. That year-over-year increase in the foreign-born population was also the largest since 2010, excluding the pandemic years when comparable data were not available.

Strikingly, the strong majority of net new immigrants to the U.S. in 2023 came from Latin America. Of the 1.6 million increase in the foreign-born population between 2022 and 2023, 76% of the increase was people born in Latin America: 49% from Central and South America, and 27% from Mexico and the Caribbean. That’s a large jump in Latin American immigration from the earlier years of the pandemic period (2019-2022) and a huge increase from the 2010s, when Asian immigration dominated.

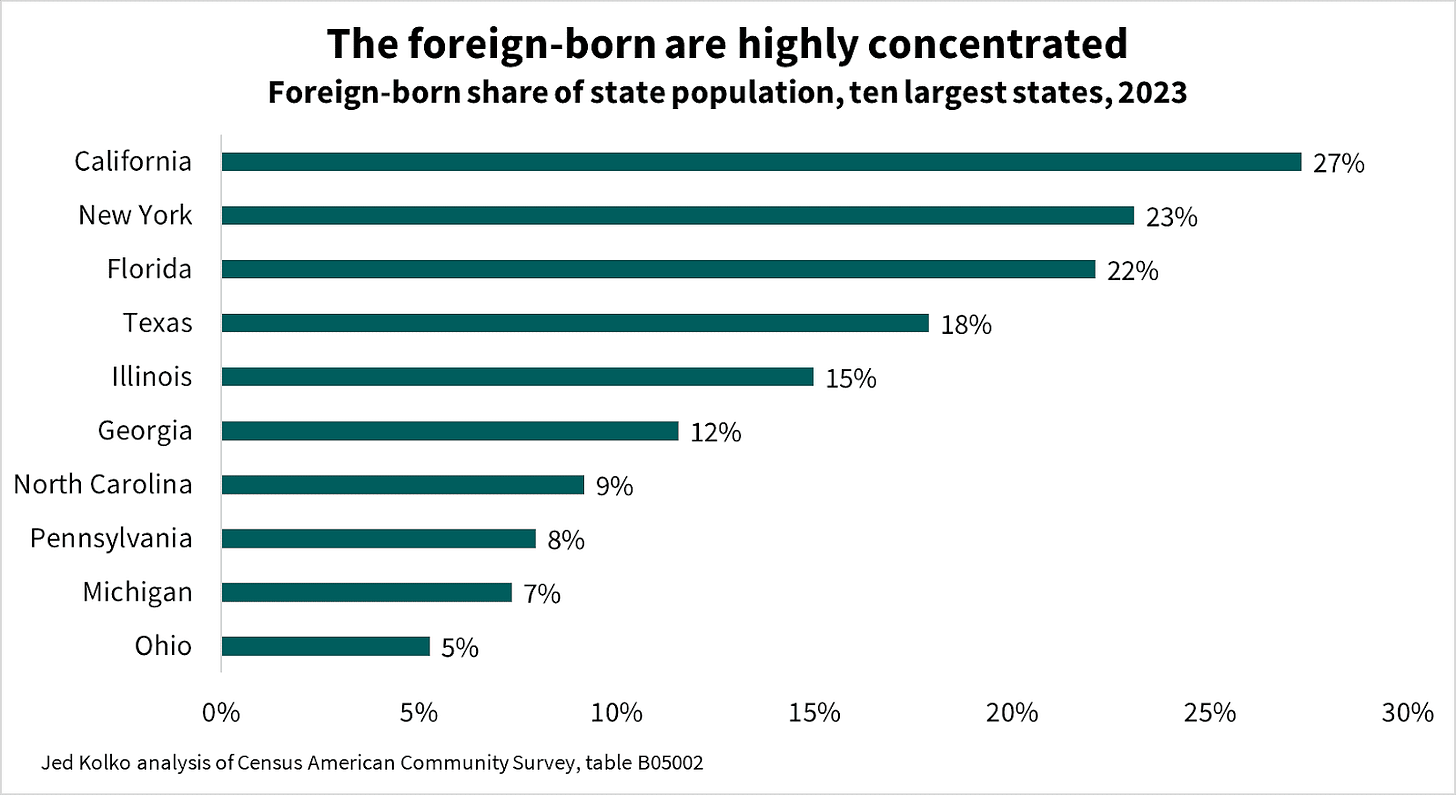

Within the US, immigrants are geographically concentrated. In California, 27% of its 2023 population was foreign-born, the highest among all states. The foreign-born share was above 20% in New Jersey, New York, and Florida, as well. At the other extreme, less than 3% of Mississippi, Montana, and West Virginia residents were foreign-born. Larger and more urban states tend to have higher foreign-born share, though North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Ohio have foreign-born shares well below the national average of 14.3%.

Since 2019, the foreign-born population has increased notably in the southern states of Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee, as well as in Indiana and Pennsylvania. But the foreign-born population was almost unchanged in Arizona, California, Nevada, and Oregon over this period.

Next month, we’ll get a lot more insight into the characteristics of recent immigrants when Census releases the real goldmine -- the microdata -- which supports more customized analyses.

Sorry. The immigration data puzzle isn’t resolved, and it could take years

Today’s new ACS data will be the basis for the immigration component of Census’s 2024 population estimate, due in December, along with revised 2023 population estimates.

The 2023 ACS reported 1.7m foreign-born residents who were abroad one year ago, which is the key input into the Census immigration estimate. That key input has been highly correlated with the final revision of the Census immigration estimate since 2010 (the correlation is .91). If this strong prior relationship holds, I estimate that the new ACS figure of 1.7m foreign-born, abroad one year ago, implies that the Census population estimate for 2023 will be revised to over 1.4m. That’s 300,000 more than the original Census 2023 immigration estimate of 1.1m published in December 2023, but still way below the CBO’s 2023 estimate of 3.3m.

In other words: Using concurrent 2023 ACS data rather than lagged 2022 ACS data doesn’t do much to close the gap between the Census and CBO estimates.

The fact that new high-quality ACS survey data probably won’t raise Census’s 2023 estimate much makes me put more weight on the Census estimate than I did yesterday. But it also raises my uncertainty about what the actual level is. I’d love more careful research about how much surveys might undercount immigrants and how much might administrative data overstate immigration, but in the meantime I, and other economists, need to update our beliefs.

I also have nagging questions about the feedback loop between ACS survey data and Census population estimates.

Remember that ACS survey data are controlled to Census’s population estimates — not just to the overall population estimates, but also to estimates for specific groups based on age, sex, race, and Hispanic/Latino ethnicity. Today’s new 2023 ACS results are controlled to the 2023 population estimates, whose immigrant component was based on 2022 ACS results, which were controlled to 2022 population estimates, whose immigrant component was based on 2021 ACS results… and so on. I don’t have a guess and don’t know how to calculate how much this recursive interdependence between the ACS survey data and the population estimates might cause any big, sudden change in actual immigration levels to be reflected more slowly in ACS data than it should. (Remember, ACS data and sample weights, unlike the population estimates, do NOT get revised.)

Still, the new ACS data can help study the effect of immigration in other ways. Economists sometimes look at the variation across states or occupations or industries to make conclusions about overall patterns. Correlating new ACS data on changes in states’ foreign-born population, for instance, with state job growth or unemployment rates or wages could help assess the impact of immigration on the economy and, implicitly, the level of immigration.

And the Census Bureau is researching how to incorporate short-term fluctuations in migration more quickly and to reduce any undercount of immigrants in living situations that are more challenging to survey. There might be methodological improvements coming — and lots of research about how they change the estimates.

Economists will keep busy.

What the immigration puzzle shows about how the statistical sausage gets made

Estimating immigration looks like a mess: multiple raw data inputs generated far-apart estimates, published by different agencies in different data products, that need to be triangulated, reconciled, and revised.

But, it’s amazing that this debate can happen at all, and it’s only possible because of the wealth of statistics that are collected, disseminated, and documented. For each of the most important economic and demographic indicators — not just immigration — the statistical system creates multiple measures that often disagree and need to be reconciled.

For the most part, having multiple ways to measure things is a feature not a bug. The many measures of a given indicator often differ in speed, comprehensiveness, or granularity. Initial estimates based on early available data get revised when more comprehensive or detailed data become available; employment, GDP, and population estimates all work this way. Different measurements also reflect conceptual differences. Just as Census surveys of the foreign-born and border-patrol encounter data are intended to measure different aspects of immigration, the two leading inflation measures are answering slightly different questions about the prices consumers face.

Furthermore, it’s a feature, not a bug, that federal statistics are often published at multiple levels of detail.

The 2023 American Community Survey data was released this morning as a set of hundreds of tables on pre-selected topics, and the microdata will follow next month for researchers who want to dig deeper. Most major data releases include a narrative summary, charts, tables, and detailed data. This offers something for everyone, at all levels of data familiarity; it also reinforces transparency. You can’t fudge the numbers in a press release for long if researchers can see the underlying data.

Of course, the wealth of data can be maddening. The burden is on the data user to decide which measure to use, how to combine them, and how to interpret them. But even this burden is, in part, a feature rather than a bug. The statistical agencies are reluctant to steer users toward interpretations or conclusions, in an effort to maintain their independence from politics and partisanship. As BLS describes their just-the-facts stance on their website: “If asked, ‘Is the glass half empty or half full?’ At BLS, we see an 8-ounce glass containing 4 ounces.”

In other ways, though, the burden on data users is definitely a bug. The agencies’ sites can be hard to navigate, and specific data are often tricky to find. I happen to know that the key data point from today’s ACS release for estimating immigration is the number of foreign-born residents who lived abroad one year ago, and that data point is on line 28 of table B07007. But I know that only after closely reading methodology documents, talking to staff, and digging through pages of search results and table shells.

The fragmentation of the U.S. statistical system adds to the challenge. There are thirteen principal statistical agencies, including the Census Bureau, BLS, and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). They are in some ways independent and in other ways interdependent, often relying on each other for key inputs into their own products, and sometimes seem to overlap. Both BLS and BEA produce inflation data, all three publish wage or income data, and so on. Statistical agencies — and sometimes even divisions or products within one agency — use different conceptual definitions, different geographic definitions, or different occupation and industry taxonomies. There’s typically detailed documentation for individual data products and releases, but much less documentation and guidance about how to compare, contrast, or combine data from different programs or agencies. That’s left to users to figure out.

Occasionally the agencies flub. In recent months, BLS has had multiple instances where some users ended up getting access to data or technical explanations earlier than others. Census users have had their own frustrations, over plans and communications around new respondent-privacy protections that would make data less accurate and usable. The statistical system needs to invest more in user experience and in collecting and incorporating user feedback. Data users should take advantage of every opportunity to be heard, such as commenting on Federal Register Notices and participating in user groups and advisory committees.

All that said, the statistical agencies face real and serious external challenges. Rising costs and tight budgets threaten critical data products; declining survey response rates require new approaches; and the risk of inappropriate political interference is always near. Still, they produce an immense range of data, are widely trusted, and are careful and transparent. The US statistical agencies are global leaders in many areas of international coordination. And the technical staff at Census, BEA, and BLS who have answered my technical questions over the years are, without exception, responsive, patient, knowledgeable, and dedicated.

Measuring immigration and everything else that matters is messy, hard, and important. We are fortunate to have data and experts we can trust to help solve these puzzles.

Questions about birthplace and citizenship are not currently asked on the decennial Census.

Here’s a good overview comparing survey and administrative data on immigration. See also detailed explanations and comparisons by CBO and Census. Census “routinely cautions against” using CPS survey data for immigration estimates because of its small sample size, as CBO does; note that this is a Census staff working paper rather than the official views of the U.S. Census Bureau.

ACS, like CPS, also is controlled to the Census population estimates. That means neither survey yields an independent estimate of the level or growth of the population.

This doesn’t mean that the rates and percentages from the CPS are too low. The key statistics from the CPS, like the unemployment rate, are rates or percentages. Economists know about this issue and rarely use level data from the CPS.

From one nerd to another, I think I speak for the community when I say, “Thank you for your service”.

SB is probably the only place in the country where an economist would get that kind of welcome! 🤣

A little deep in the weeds for me, but I appreciate the author for contributing the piece and SB for publishing it!