Breaking down the election results

What county-level data shows us about the swing toward Trump

Today we’re welcoming to the team economist Jed Kolko, who’ll be writing a monthly column for Slow Boring. Jed served for two years as Under Secretary for Economic Affairs in the Department of Commerce, where he oversaw the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Economic Analysis. He was previously chief economist at Indeed and Trulia.

Jed has written for us before, about the kind of economic research policymakers actually need (an article that holds the honor of being our only post with more likes than comments) and about how newly released data helped unlock an immigration puzzle. In his new column, he’ll take a similar data-driven approach to answering some of the questions we think Slow Boring readers are most interested in, starting with what, exactly, happened on Tuesday.

Preliminary 2024 Presidential election results at the county level show a widespread swing toward former President Donald Trump between 2020 and 2024. Trump did better in 2024 than in 2020 in counties that cover 92% of the US population.

In 2024, as in most recent presidential elections, few counties had dramatic swings relative to 2020 that diverged from the national swing. That means the 2024 county vote pattern was little changed from 2020. The correlation between Trump’s shares of the vote in 2024 and in 2020 across counties was .99 — that is, the bluest places in 2024 were overwhelmingly the bluest places in 2020, and the reddest places four years ago were, by and large, the reddest places this time around.

Still, changes in how counties voted in 2024 versus 2020 reveal key shifts that drove the national results. (See the end of this post for methodological notes, data sources, and caveats.)

Let’s start with geography. Urban counties showed a bigger swing toward Trump than suburban and exurban counties, smaller metros, and rural areas. Of course, Harris did best — as did Biden four years earlier — in urban counties, but the 10-point swing toward Trump in urban counties was larger than swings in other places.

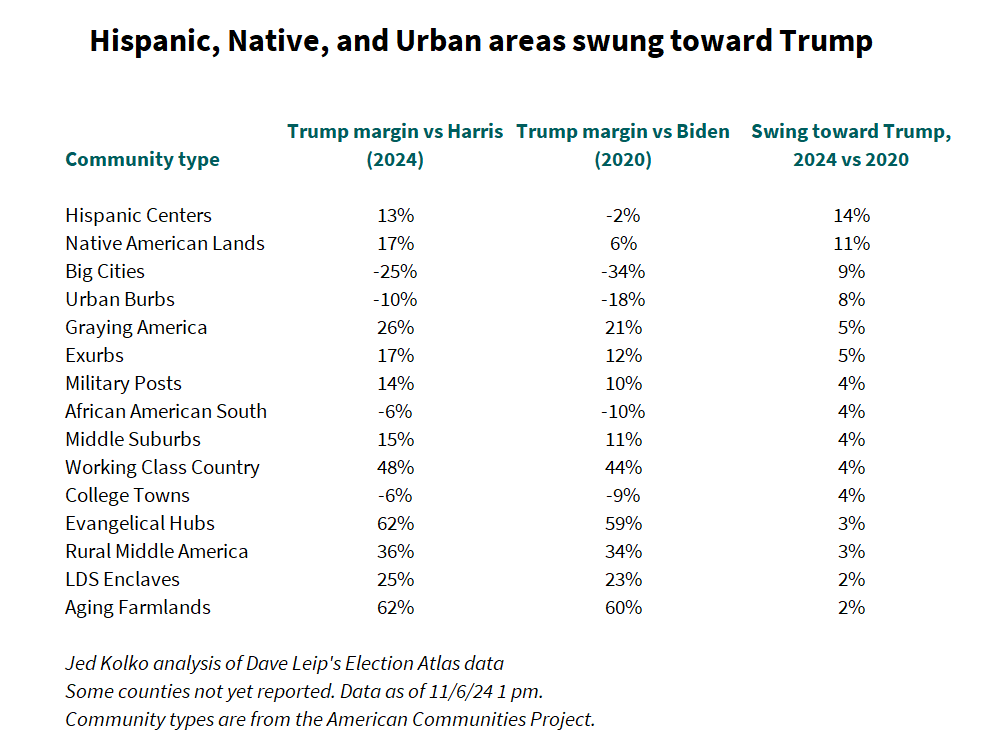

A more refined county classification from the American Communities Project, which groups counties based on their demographic, economic, and other factors, confirmed that Trump did better in 2024 than in 2020 in all types of communities, with larger swings in some places than others. Big cities, Hispanic centers, and Native American lands swung most toward Trump in 2024. The reddest communities — aging farmlands, evangelical hubs, and working class country — swung less, as did still-blue college towns and LDS (i.e. Mormon) enclaves, where Trump has repeatedly gotten smaller margins than previous Republican presidential candidates.

Going one step more granular to individual metros, many swung more than 10 points toward Trump in 2024 versus 2020, including New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, and Miami, as well as heavily Hispanic/Latino metros in Texas, California, and the Southwest. Just a handful of metros swung a bit bluer in 2024, mostly in the Mountain West and Pacific Northwest, including Salt Lake City, Tucson, and Colorado Springs.

Looking across all counties that have reported election data, the geographic pattern of the 2024 vote was less polarized than in 2020 in some ways. Most notably, counties with a higher share of Hispanic residents were more likely to vote for Harris than for Trump, but by smaller margins than for Biden in 2020. Same with higher density counties: there was a very strong correlation between county density and Harris vote share, though not as strong as in 2020. In contrast, the correlation between county education level and Harris vote share strengthened further in 2024. Density and education are themselves highly correlated, with residents of more urban counties more likely to have a college degree than those of more rural counties, but higher-density counties swung toward Trump, while highly educated counties did not.

What about the economy? Voters said the economy was their top issue in the presidential election. At the same time, on many measures the economy has been a lot stronger than voters’ perceptions, so it’s unclear how much we’d expect voting patterns to reflect economic realities. These preliminary county results suggest that better local economic conditions on some measures might have given Harris a small boost, but only around the edges.

Because local economic conditions and performance can be highly correlated with other local factors — during the pandemic, for instance, job losses were steeper in urban counties — I look at the relationship between local economic factors and the 2024 vote swing, while controlling for county demographics, education, and density.

Two economic factors were correlated with local voting outcomes. A higher unemployment level in the year leading up to September 2024 was associated with a bigger swing in the county vote toward Trump in 2024 versus 2020. Same with a bigger rise in unemployment between the year before the pandemic and today. Unemployment rates were less strongly correlated with the swing in the local vote than other factors like Hispanic share, education, and density, but were still statistically significant.

A second significant factor was local cost of living. Counties with a higher cost of living swung more toward Trump in 2024 relative to 2020. Expensive counties tend to be blue places like big coastal cities; Harris won most of these pricey counties, but by a smaller margin than Biden did in 2020, when controlling for demographics, education, and density.

Unfortunately, there’s not a good measure of the change in the cost of living — i.e. inflation — at the county level. The main driver of differences in the local cost of living is housing costs, which vary much more geographically than the costs of goods or other services. But rising home prices make homeowners richer while they reduce affordability for renters, so could be good for some people and bad for others. Controlling for the same set of factors, counties where the Zillow home price index rose faster between 2019 and 2024 swung slightly less toward Trump.

Local job growth did not have a statistically significant relationship with how the 2024 vote swung in a county. Nor did the amount of local spending per capita by the federal government under the three main Biden Administration investment programs (the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the CHIPS Act) based on data on the Investing in America website.

Yet in another way, Biden Administration economic priorities might have affected county election outcomes. A higher manufacturing share in a county was associated with a smaller swing toward Trump in 2024 versus 2020, holding other factors constant. To be sure, manufacturing-heavy places still tend to vote Republican, but to a lesser extent in 2024 than in 2020.

In all, local economic conditions played at most a minor supporting role in explaining why some counties swung more or less toward Trump in this election relative to the previous one. Places with higher unemployment and a higher cost of living swung more toward Trump, but the racial/ethnic mix, educational attainment, and density were all more important factors.

Polarizing topics on the national stage don’t necessarily translate into local differences swinging the vote. The economy may have been voters’ top concern, but local economic conditions had only a marginal impact on county-level results.

Notes and sources:

County-level election results are from Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections, updated midday on 11/6/24. This analysis excludes Alaska, for which county results are unavailable. Election data had not yet been reported for 176 counties, covering 5% of the U.S. population, including Maine, Massachusetts, Mississippi, and New Hampshire.

Connecticut data are for legacy counties, not the current planning regions.

Correlations and regressions in this analysis are weighted by either the total vote or population of the county. Regression results are interpreted using robust standard errors and standardized coefficients.

Margins and swings are calculated before rounding.

Race, ethnicity, and age data are from Census population estimates. Education and the industry mix are from the Census American Community Survey. Density is tract-weighted household density. Unemployment rates are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics; job growth is from the BLS Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages. Local cost of living data are experimental county regional price parities from the Commerce Department’s Regional Economic Research Initiative. Home prices are from Zillow. Federal investments under BIL, IRA, and CHIPS are from invest.gov. The 15-type county classification is from the American Communities Project.

County-level analysis is well suited for analyzing county-level conditions and factors, like the local unemployment rate or density. But county-level relationships don’t necessarily imply individual behaviors (this is the “ecological fallacy”): higher-education counties voted more for Harris, but the people in those counties who voted for Harris might or might not be the more highly educated residents of those counties. County-level analysis is poorly suited to analyzing factors that vary little across counties — like gender — or to making inferences about groups that are a small minority of a county’s population.

Eh. I am going to maintain that Charles Lehmans article on disorder is at the core of Trumps victory, or should I say the Democrats loss.

A majority of people did not vote for Trump, they voted against “disorder”.

Of course, people feel like the economy is bad when they see homeless people laying around the streets doing drugs. (yes I know this is only a small percentage of homeless… But it’s the majority of the visible homeless).

Of course, people think crime is up when they see mass shoplifting operations on TV and then go to their store and see their deodorant locked behind plexiglass.

Of course people are frustrated when they see millions of migrants claiming asylum because they were in danger… but knowing full well they were here for economic reasons.

If Democrats want to win, they need to advocate for policies that make society, more orderly, organized, fair, and rule driven.

And I did not vote for Trump, but the majority of my friends did… And I know why.

https://open.substack.com/pub/thecausalfallacy/p/its-time-to-talk-about-americas-disorder?r=3gj6y&utm_medium=ios

>Places with higher unemployment and a higher cost of living swung more toward Trump

Stimulate harder -> raise particularly salient CoLs -> get hammered on "inflation"

Muddle through with half-assed austerity stimulus -> weak recovery -> get hammered on "unemployment"

Macroeconomically damned if you do, damned if you don't...the best possible situation seems to be inheriting a strong economy someone else already paid the price for fixing.