Avoiding a data center electricity price apocalypse

With appropriate policy design, regulation, and planning this can be a win-win

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote that there is plenty of water to build more data centers. It’s not just that the amount of water they use is often exaggerated for rhetorical effect — it’s that the United States has plenty of water, and a lot of our supply could be used for higher value activities.

The situation with data centers and electricity, though, is different.

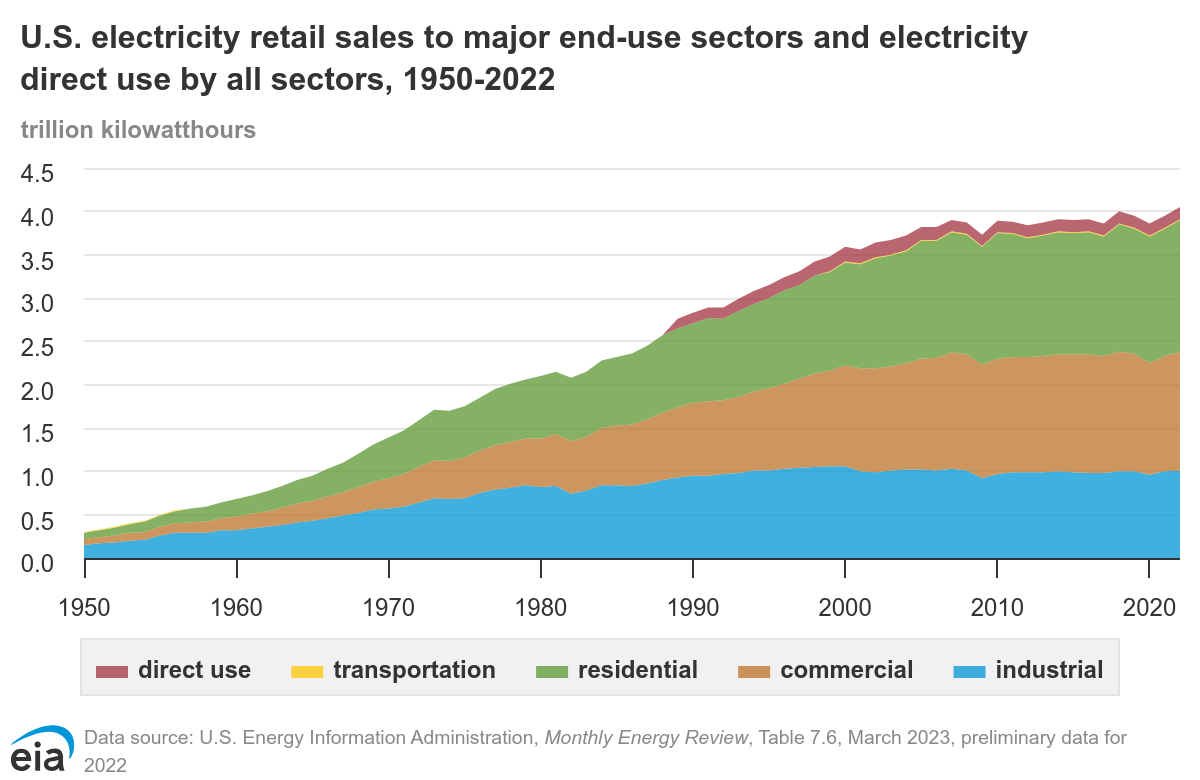

A big data center isn’t like a lamp that you can just plug in and turn on. If you want to bring a new data center online, in addition to generating more electricity to keep it running, you need to build new infrastructure just to be able to deliver the required power. And utility regulators are already wrestling with load growth. For most of the 21st century, electricity use in the United States wasn’t really increasing. The increasing energy efficiency of home appliances and the decline of American manufacturing outweighed population growth, an increase in the quantity of digital devices, and the early buildout of internet infrastructure.

That’s changing because of household electrification. Plug-in hybrids, EVs, heat pumps, and induction stoves are more energy efficient on net than things that rely on small doses of combustion. But unlike earlier iterations of appliance efficiency, these clearly require more electricity from the power grid, not less. The rising bills consumers have seen this past year are not all because of data centers (note that the increase is unusually high in Maine where there are few data centers and unusually small in Virginia where there are many), but it is important context for the data center issue.

AI companies are flush with investor cash these days and eagerly racing to spend on both talent and infrastructure. This raises the risk that deep-pocketed tech companies could come to town and overbid other payers for the limited electricity and delivery capacity that already exists, creating a situation in which the typical person’s experience of the AI revolution is mostly that the cost of living goes up. But there is also an opportunity here to force companies that are eager to get their hands on more electricity but are also relatively price-insensitive to pay the cost of new infrastructure they need and that would also serve a wide range of other users. Which outcome actually happens is going to depend on a lot of different policy choices made by a wide range of actors.

As far as I can tell, there isn’t a simple bumper sticker answer to what the best policy approach is. But I do think there are some broad principles that can help people in the general politics and policy worlds ask the right questions about the nitty-gritty details of utility regulation and grid management:

Inventing new, economically valuable ways to use electricity is good on net, but the challenge for regulators is to ensure that it’s actually good for most people.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.