After the Green New Deal

We need a clean energy strategy for a full employment economy

The Green New Deal stands in some circles as a byword for progressive energy policy excess. And as outlined by the Justice Democrats and others on the far left, it certainly was excessive.

But it was also a potent metaphor and in many ways a genuinely important and praiseworthy effort to grapple with what is, I think, the central dilemma of contemporary progressive politics: Left-of-center elites really want to address the problem of climate change, but working class voters do not want to bear localized economic costs for global benefits.

The Green New Deal, conceptually, is a framework for addressing this dilemma. You start with the premise, which was true circa 2016, that interest rates and inflation are low and macroeconomic outcomes could be improved via fiscal stimulus. Then you join it with the premise, which was and still is true, that there are negative externalities associated with carbon dioxide emissions and also adaptation needs associated with climate change. The solution is a program of fiscal stimulus designed to spend money on emissions-reducing policies and climate adaptation.

Shorn of ideological excess and some of the specific GND terminology, this is, in fact, the approach that the Biden administration took toward climate policy.

Both the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act included large investments that skewed green. And if the macroeconomic circumstances had remained unchanged from 2016, these programs would have been huge winners, because the key thing about fiscal stimulus in a depressed economy is that the stimulus is beneficial, even if the program you spend the money on has no value. One of Keynes’s most famous points is that if the economy is sufficiently depressed, paying people to dig holes and then fill them back up again would have economic benefits. The hole-digging itself is pointless. But the hole-diggers would have extra money in their pockets to spend, presumably on stuff they do value, and that extra spending would “crowd-in” additional employment and investment in producing goods and services to sell to the hole-diggers.

Keynes’s point was not that you should actually respond to a depression by paying people to do pointless tasks — it’s always better to do something worthwhile than something worthless. His point was that the macroeconomic benefit of stimulus does not hinge on the object of the spending being worthwhile. That’s the magic that makes the Green New Deal logic work. The architects of the program (Democratic Party elites) do believe that decarbonization is worthwhile, which is why they structured it to decarbonize, but the voters enjoy the macroeconomic benefits whether or not they care about decarbonization. It works because good macroeconomic policy works, and the macroeconomic policy is good because the economy needs stimulus.

The problem, though, is that if there’s no depression, we don’t need a New Deal.

This applies, not just to the specific, far-left climate policy framework that went by the name Green New Deal, but to the considerably more mainstream version that Democrats eventually pursued. In a full employment economy, paying people to dig ditches and fill them up again is ruinously wasteful. Subsidizing green investments is not ruinously wasteful, but it is still costly, which means that it’s valuable only insofar as you actually care about the emissions-reduction benefits. The GND premise aimed to make climate policy workable by structuring it in a way that would have broad economic benefits. That’s the right idea! But in a full employment economy, you need to completely restructure policy ideas that were formulated to fight a recession.

The IRA’s emissions impact is varied

Not all of the Inflation Reduction Act’s many provisions had to do with climate and energy. But focusing on the climate provisions, the Rhodium Group estimates that most of the emissions reduction comes from accelerating the decarbonization of the electricity sector. This is particularly true in their central tendency scenario, where fully 75 percent of the emissions cuts stem from clean electricity. Notably, these provisions account for less than half the spending.

The carbon capture provisions are a small share of the emissions reduction, but also a small share of the spending. The clean hydrogen provisions seem like a waste of money, but Joe Manchin really liked them. And then you have the various transportation subsidies, which account for a much larger share of the spending than of the emissions reduction. The reason for this, as Jason Furman explained in economics jargon, is that they “have a substantial inframarginal cost.”

In other words, totally separate from the climate benefit, electric cars have some advantages over gasoline cars, as well as some disadvantages. Because of the advantages, some consumers are happy to buy electric cars without subsidy. And electric car technology is improving significantly faster than internal combustion engine technology, so even absent subsidy, you would expect the electric car market share to grow over time. This means a large share of the subsidy is going to people who would have bought an EV even without the subsidy, leading to a poor cost-benefit profile.

This is where the ditch-digging becomes relevant.

If the economy were in a depression, it would still be true that an EV subsidy with a large inframarginal cost is kind of poorly targeted. But the poor targeting wouldn’t really matter. The extra money in consumers’ pockets is stimulative, and the policy still does have beneficial climate and pollution impacts. It would be logistically challenging to design a perfectly targeted EV subsidy program, so as long as EV subsidies are economically beneficial, you might as well throw them in. It’s a lot better than digging a ditch! But in a framework where there is no depression and you don’t need a New Deal, these considerations of relative cost matter.

Tax and spend

Another way of making this point is that IRA-style policies would have been perfect back in 2009-2010, when Democrats were trying and failing to pass a carbon pricing bill.

In those days, inflation and interest rates were low; the economy needed more stimulus. If they could have written a second reconciliation bill that dumped hundreds of billions of clean energy subsidies into the market, most Americans would have been better off in material terms through the indirect stimulus benefits. What’s more, while most voters don’t care very much about climate change, most do care about it a little. They believe that it’s real, and they would like the government to do something about it. So if you could do something that was broadly economically beneficial and didn’t really inconvenience anyone very much, and also reduced emissions, why not?

At the time, it was all about pricing, which was a very tough sell politically.

That said, it’s worth revisiting the basic case for pricing. John Bistline, Neal Mehrotra, and Catherine Wolfram model the IRA’s climate impact and find that it’s roughly equivalent to a $10/ton carbon tax.

The difference is that the subsidy approach to energy policy costs a bunch of money, whereas the tax approach raises revenue. So even if you fully rebated the carbon tax revenue, swapping subsidy for tax would still lower the budget deficit.

And a full employment, inflation-constrained economy is the opposite of the one in which Keynes’s hypothetical ditch-diggers found themselves — the lower deficit has a small-but-real positive impact on all kinds of things thanks to lower borrowing costs. If you swapped the subsidies for a rebated tax, mortgage rates and auto loan rates would be lower. What’s more, even though nobody likes to pay higher taxes, a tax-and-rebate scheme leaves the bottom 60 percent of the population with more money.

It’s still true, of course, that making this kind of swap would be politically difficult. The point, though, is that a subsidy-led climate policy made sense when that kind of policy had broad economic benefits. The macroeconomic situation has changed, but the political imperative to make energy policy with broad economic benefits remains. You need to change the policy to fit the circumstances.

Paths to green growth

While voters don’t want to pay a big economic price for emissions reduction, there are emissions-reducing steps we could take that would have negative economic costs:

Change historic preservation rules so you can install rooftop solar panels

Change regulations to make it easier to build interregional transmission lines

Pass something like the Manchin-Barrasso permitting reform bill

Fix the NRC so it starts licensing new reactors again and evaluates nuclear projects using a comprehensive cost-benefit framework

Make it easier to do geothermal drilling on public lands

Make it easier to drill Class VI wells for carbon storage

Stop saddling clean energy projects with “everything bagel” requirements around labor and community benefits and just let people build

It’s also important for blue state politicians to stop thinking in terms of state-level climate targets and start thinking about comprehensive impacts. The electricity grids in New York, New England, and the Pacific Coast are already greener than in Texas and Florida, and the milder climates on the West Coast are an additional huge climate boost.

Any time you make it easier to build housing in these areas, you’re delivering a win for the economy and for the environment. That’s especially true for transit-oriented development, but crucially, it’s true even for development that isn’t transit-oriented. The important thing is to make economic policy choices that make sense on the merits, just as a Green New Deal makes sense as economic policy if there’s a huge recession and if the economy is in need of stimulus. But when there isn’t a recession, what the economy needs is supply-side regulatory reforms. If you care about the environment, you want to make sure those reforms aren’t just unleashing tons of coal-fired power plants and air pollution on the country. But if you care about economic growth and broadly shared prosperity, you can’t make blocking fossil fuel projects the center of your regulatory politics. You need to identify regulatory barriers to clean growth and work aggressively and decisively to dismantle them.

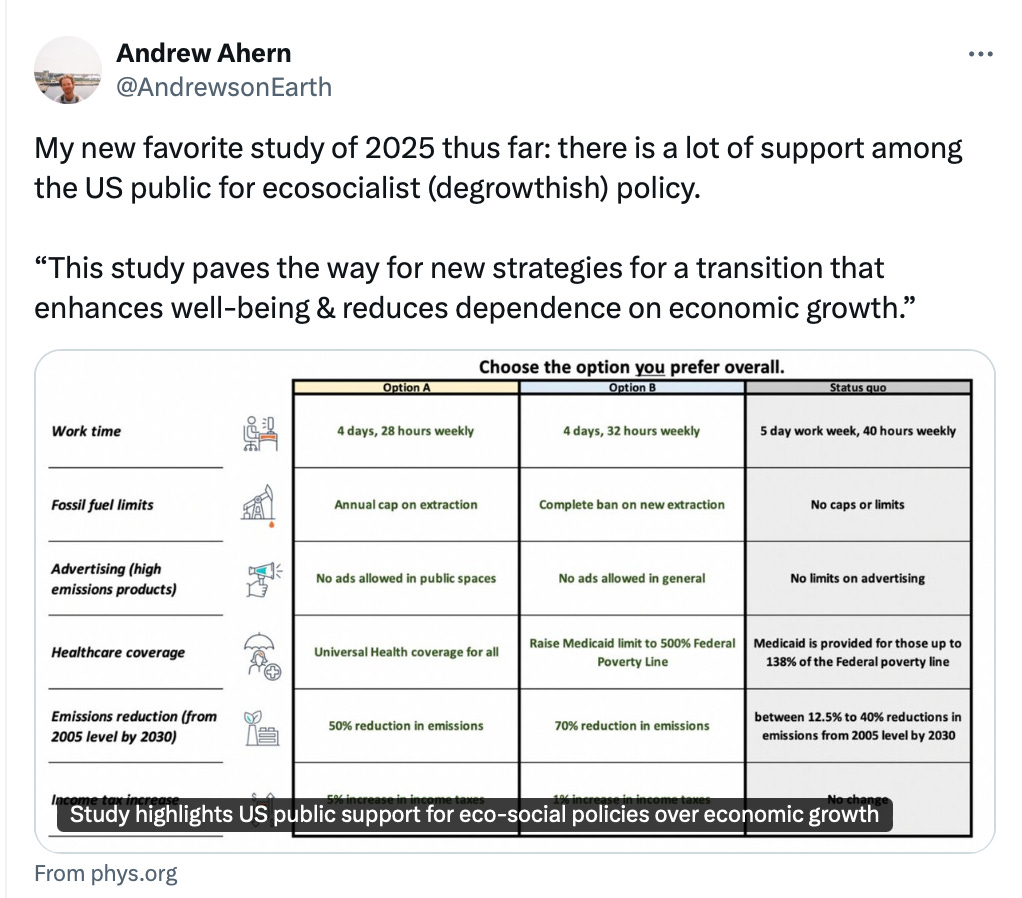

And you need to decide that you really do care about economic growth and broadly shared prosperity, despite the people who continue to push ridiculous degrowth policies as their preferred climate solution.

As I’ve noted many times before, the Democratic Party is decidedly not a degrowth party. When good GDP data comes in, the Biden White House brags about it.

But Democrats do tend to silo their policy development so that energy issues are outsourced to experts and advocates focused on climate, leaving them divorced from economic policy. That doesn’t work, and it doesn’t make sense. Economic policy decisions should be informed by scientific facts about pollution and climate change, but they should also make sense on the merits and adapt to shifting economic circumstances. The fact that comprehensive carbon pricing is, in an idealized sense, the most economically efficient way to address climate concerns is obviously not the last word on the subject. But it is still an important structural reality, especially in a world where austerity is on the menu.

If you’re thinking about growing electricity demand from data centers, for example, it makes more sense to think about designing a sector-specific emissions fee that is used to reduce other taxes than to come up with new regulatory mandates. Or if you’re thinking about how to boost American manufacturing vis-à-vis China, it’s worth considering carbon tariffs that would level the playing field between American steel and the much dirtier steel made in China. These ideas — and the general idea of relying more on pollution taxes for revenue — are good not primarily because they will solve environmental problems in one fell swoop, but because they are good tax policy ideas. A world of fiscal constraints requires facing unpleasant tradeoffs, and taxes that reduce pollution have a relatively favorable tradeoff profile compared to other taxes or to slashing Social Security benefits.

The point, though, is that the economics has to come first. Politicians who care about the environment can push green stimulus when stimulus is needed and green deregulation when deregulation is needed and green austerity when austerity is needed. But they need to pay attention to what actually is needed.

I in principle appreciate the argument in favor of a GND in a depressed economy. I might even support it if I had trust that it would be implemented competently and efficiently. Unfortunately, I have zero trust that the Democratic party can execute a GND responsibly.

First, I no longer trust them when they say that the economy needs stimulus. They pushed for huge deficit spending in 2022, when it was clear that inflation was running high, was not temporary, and that households clearly had excess savings from prior stimulus.

Second, any GND that actually made it through congress would look nothing like the GND laid out by MY. There would for sure be pro-union rules, minority owned business set-asides, attempts to push parental leave policies on the companies involved, community review requirements designed to funnel money to non profit orgs, etc, etc.

The thing that stands out to me about the GND debate of several years ago isn't the misguided ideas about policy, but rather the misguided ideas about politics.

Dave Roberts wrote about how, sure, a Iot of the climate policies would be unpopular with the public rubes, but that's why the GND also includes a jobs guarantee and M4A. Because of "political economy" is how he put it.

GND proponents not only didn't realize that the economic parts of the plan weren't popular, they thought they'd be so popular that it would make the overall GND an electoral winner.