“Affordability” is just high nominal prices

I think Trump is totally screwed on this one

After a full year of factional infighting, Democrats of all stripes have coalesced around the idea of running on affordability. This is great on three levels:

It clearly resonates strongly with voters.

It’s a conceptual container that can hold a lot of different kinds of policy ideas.

It lets people who want Democrats to change their position on divisive cultural issues, and those who don’t, feel like they’re winning the argument.

Something that I’ve learned in my career as a disagreeable writer who loves to draw fussy distinctions is that effective practical politicians are really good at coming up with formulations that smooth over disagreements and sidestep inconvenient choices.

That impulse sometimes lands them in bad situations where they’re alienating swing voters by hyper-focusing on managing their own coalition of supporters. But in this case, point (1) is very important — the focus and sloganeering around affordability not only bridges internal gaps but also connects with voters. We’re clearly moving in the direction of a solution here, and I expect every Democratic Senate candidate and every frontline House member to run on a strong affordability message over the next 12 months.

And given the central role that affordability is playing and will continue to play in our politics, I want to raise a kind of dumb question: What is affordability, exactly?

In search of a definition

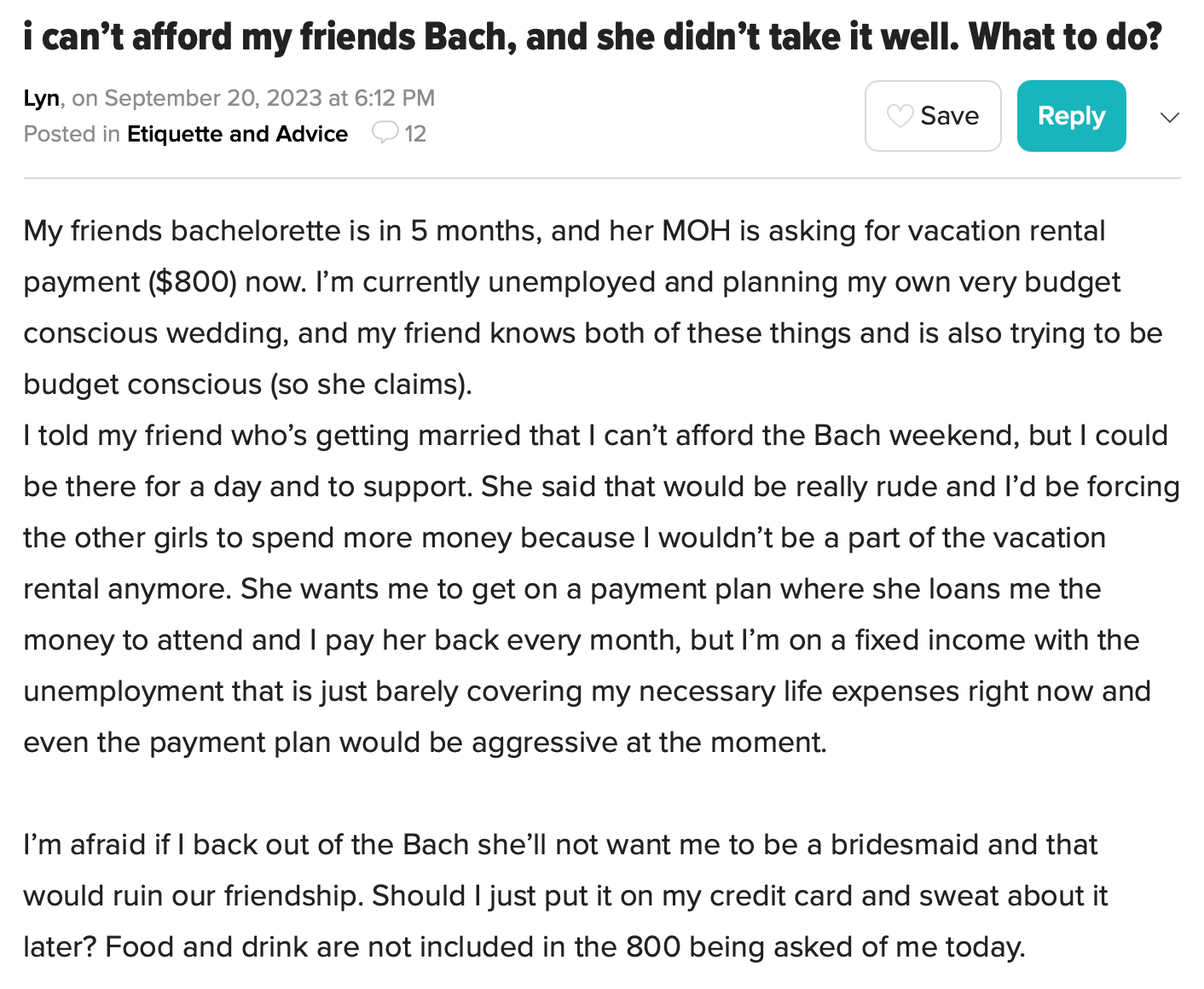

My sense of the ordinary language meaning of “affordability,” as captured in the Wedding Wire etiquette question “I can’t afford my friend’s bach, and she didn’t take it well. What to do?” is that affordability is primarily a function of prices and incomes.

Lyn says that she can’t afford the price of the vacation rental house for her friend’s bachelorette weekend because it costs $800 and she’s “on a fixed income” provided by unemployment insurance due to a recent job loss. She proposes to her friend that to save money she simply drive down for one day to hang out — i.e., reduce the price — rather than spend the whole weekend there. Of course, if she suddenly got a high-paying job offer, that might solve the problem.

The text of the question also suggests that savings goals are part of the affordability mix, because she offers as one possible solution that she might “just put it on my credit card and sweat about it later.” So lack of affordability doesn’t necessarily imply non-consumption; it could be that you feel your consumption pattern has pushed you into an undesirable household-balance-sheet situation.

Last but not least, she talks about her “necessary life expenses” — presumably quasi-fixed costs like rent, utilities, and maybe a car payment, plus groceries and whatever household supplies she purchases regularly.

I’m going through this in a slightly pedantic manner just to confirm that, to a normal person chatting in a non-political context, affordability is a holistic judgment. She’s not calling the $800 bachelorette weekend extravagant per se or even saying that it would be impossible for her to attend. What she’s saying is that $800 is too much relative to her income, her fixed costs, and her desire to avoid going into debt — she cannot afford it.

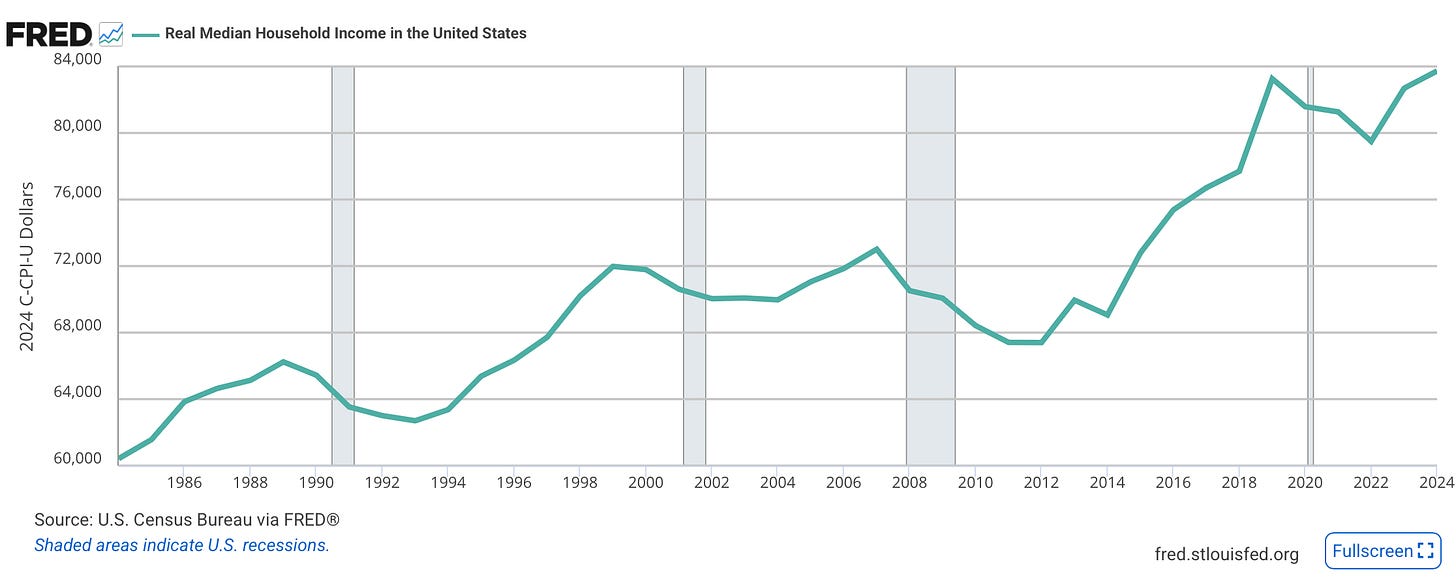

The government keeps statistics on overall incomes relative to prices, and you can see that real median household income in the United States soared from 2014 to 2019, but fell during the pandemic and post-pandemic inflation. It rebounded strongly in 2023 and reached an all-time high in 2024:

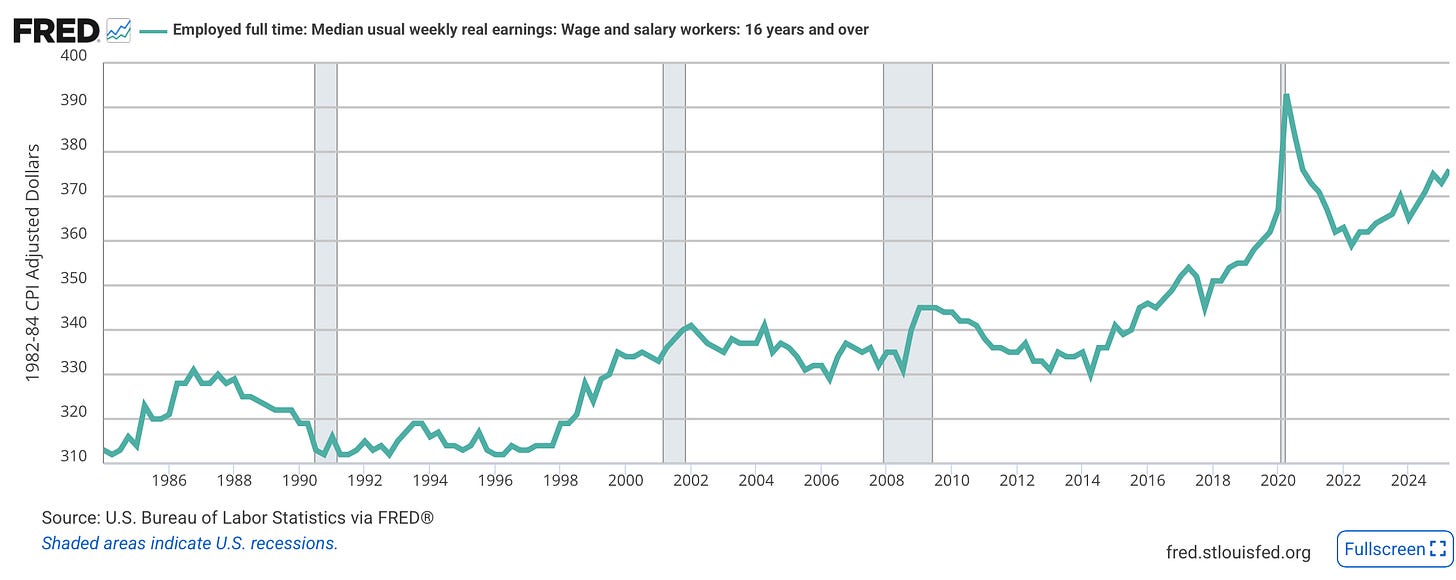

We don’t yet have household income data from 2025, but we can look at median wages, which are also higher today than they were before Covid.1 Lots of people are struggling, of course, but looking at the country as a whole, incomes have risen faster than prices.

Median household income was at an all-time high (yes, accounting for inflation) in 2024 and inflation-adjusted wages continued to rise in 2025. We also know that more people are working rather than fewer.

I think you all know that I’m not here to be Donald Trump’s discourse lawyer, but if I were working at the National Economic Council or the Treasury Department, I’d be looking at these charts and feeling pretty annoyed with the American people.

They have literally never had it so good, but they’re furious about affordability. What’s going on?

I don’t know anyone who does economic policy for Trump, but I do know a bunch of people who did economic policy for Joe Biden, and they very much felt this way 12 to 18 months ago. They also learned to their chagrin that any effort to argue with the voters blew back on them immediately. When people feel they’re living through an affordability crisis, they really do not want to see your charts and graphs.

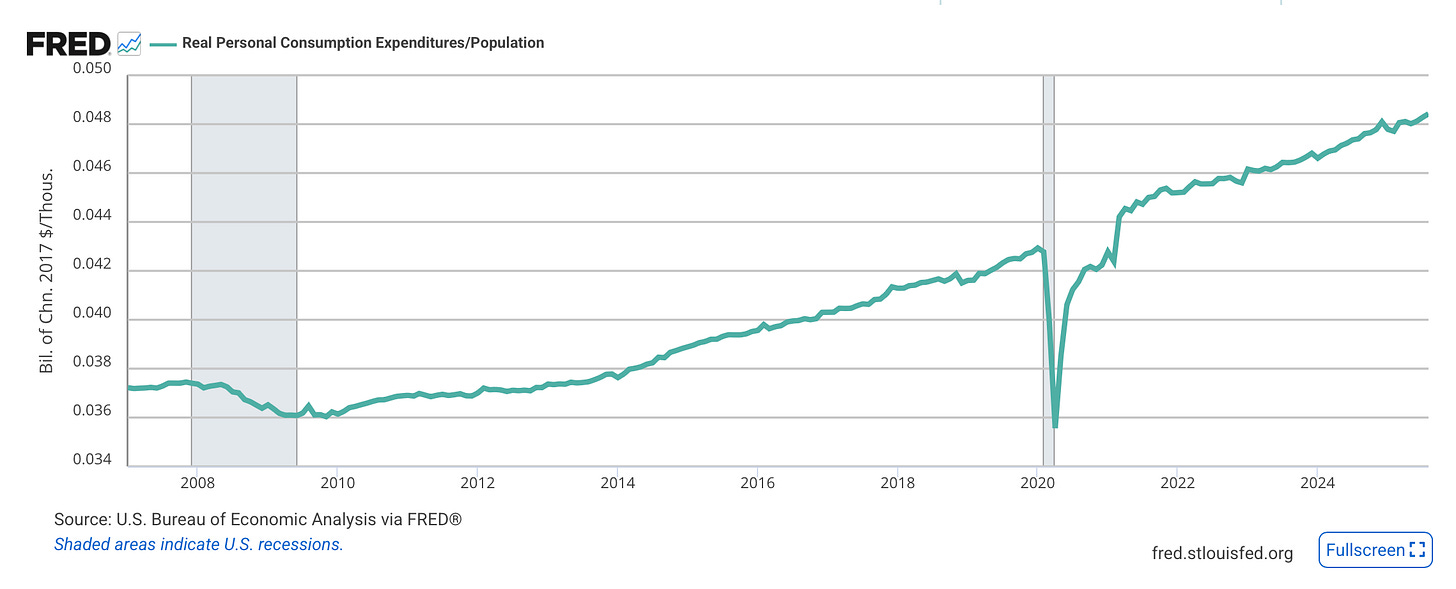

So now, in the interests of providing factual information to the public, burnishing my own bipartisan cred, and trying to tempt Trump into a politically suicidal effort to tell the voters they’re wrong, let’s look at one more chart. This is inflation-adjusted consumption spending per person, and it shows that voters in the aggregate are buying more goods and services than ever before.

This is mean, not median, so in theory Sam Altman could be the only person in America buying more stuff. But, again, we saw that median incomes and wages are at all-time highs, so that seems unlikely.

Some other things that I don’t think are going on

I flagged the issue with the bachelorette party and the credit card because, back in the Biden presidency, I considered the take that the affordability crisis was essentially a question of dissaving.

During the pandemic, the government stepped in with multiple rounds of spending to (successfully) stabilize incomes and avert hardship. But most people reacted to the situation by voluntarily curtailing their spending — they vacationed less, dined out less, and engaged in less recreation. That meant most people entered the summer of 2021 sitting on an unusually large cushion of extra cash, and most people were also pretty eager to splurge on a family trip to Disney World or a weekend in Vegas with the boys or just a lavish date night.

This sudden surge of spending fueled inflation.

I reassured myself at the time that inflation-adjusted consumption was going up, not down; in other words, people weren’t experiencing massive levels of objective material deprivation. But they were spending down their savings.

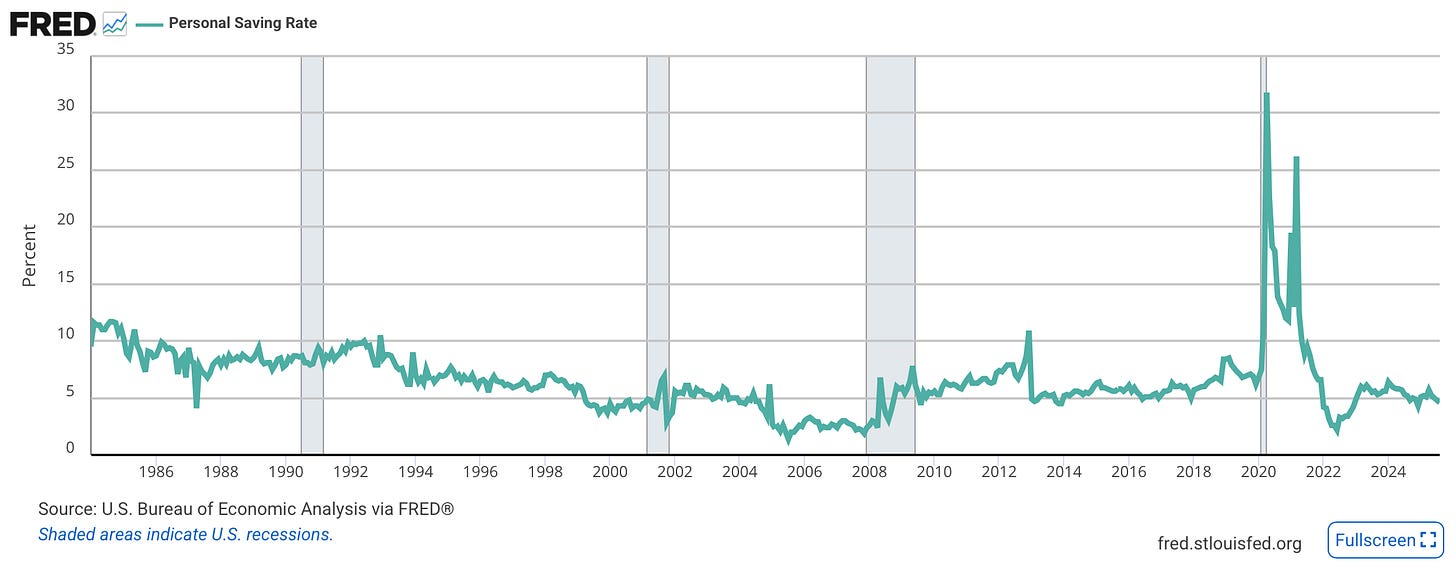

In some sense, that was probably inevitable. Still, if you’re watching the balance in your bank account tick down, down, down every month, it’s natural to feel like a cost-of-living crisis is engulfing you and your family. But after falling sharply during the Big Inflation of 2022, the personal savings rate has rebounded to a pretty normal 21st-century level. What stands out in retrospect is the very low savings rate of the second George W. Bush term. At that time, a lot of people were taking out aggressive mortgages or tapping into home equity loans to finance their personal consumption.

The stock market is booming right now, but there’s nothing particularly fishy going on with household finances. I read a New York Fed report last week that said household debt just reached an all-time high, but that turns out to be a purely nominal figure that doesn’t adjust for population growth, inflation, or incomes.

Another take that I’ve toyed with is that “affordability” is essentially relative price shifts.

I like to quote Agatha Christie’s recollection in her memoir that when she was a young mother, she never thought she’d be rich enough to own a car or so poor that she couldn’t afford a live-in nurse and maid. If you compare the average American in 2025 to the average American in 1985, they have a much better television and also access to a much wider array of programming. Their inflation-adjusted consumption of telecommunications services has improved dramatically. But it is harder to afford child care or a babysitter or other labor-intensive services.

I think there’s something to the idea that relative price shifts over the course of my lifetime have been unfavorable to a kind of commonsense view of “the good life.” A large share of our increased real consumption is dramatically more streaming video, which has probably had a net negative impact on human welfare. The quality and quantity of medical treatments available to older people is a lot better than it used to be. But while this is very good and important, it doesn’t necessarily speak to the typical person’s ability to achieve basic life goals in terms of employment, housing, family formation, and fulfilling work.

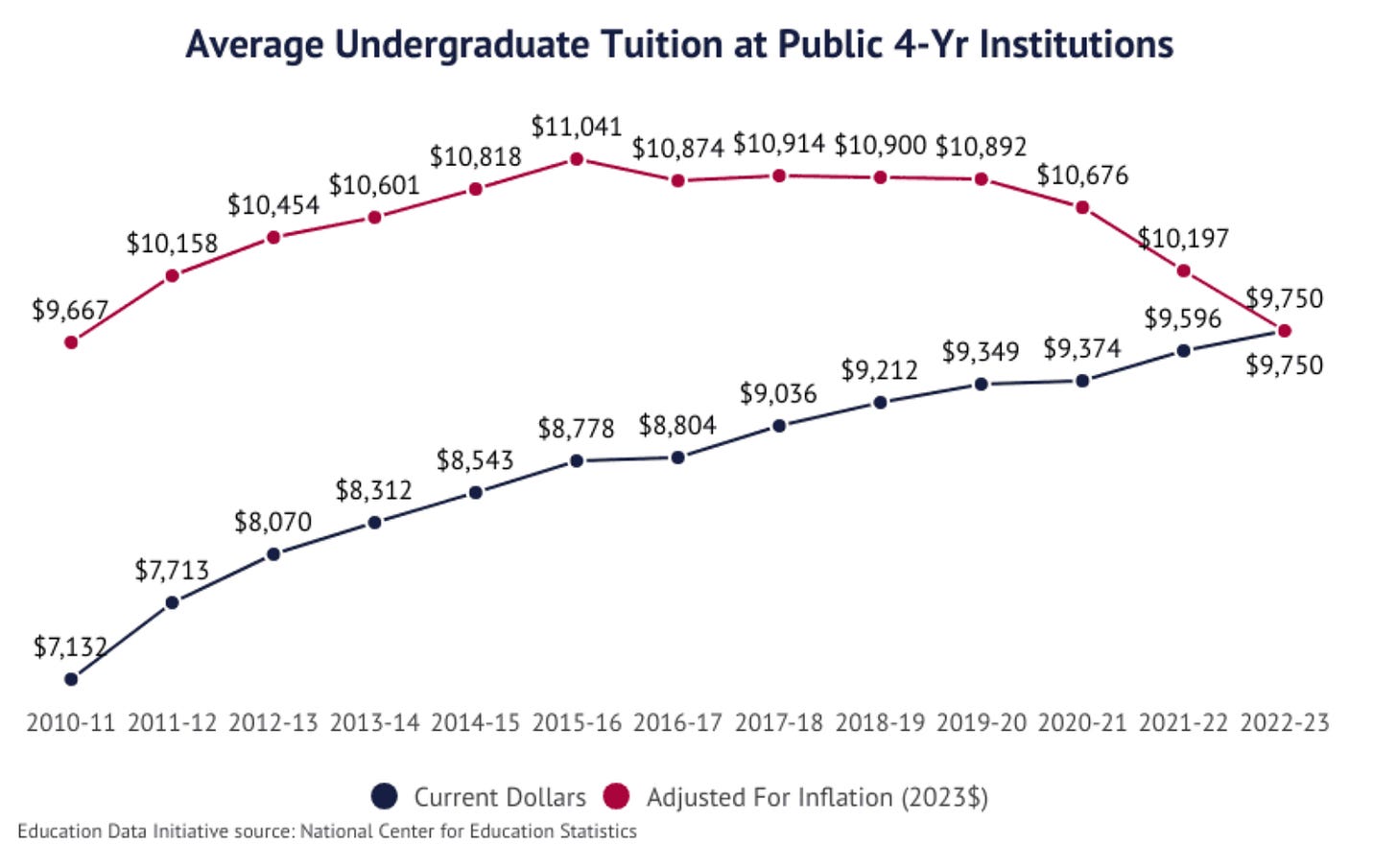

But relative prices are always shifting. And I don’t really buy the theory that they suddenly became especially unfavorable over the past five years. What’s more, some things have gone in the opposite direction. College tuition has been falling in inflation-adjusted terms for years now, and since incomes have been rising faster than inflation, that means college affordability — which used to be a huge point of dispute — has been getting a lot better. And nobody cares.

One reason they don’t care, of course, is that inflation-adjusted tuition has been falling partly because inflation has been high. The nominal dollar tuition keeps going up!

Similarly, I love housing, so I’m always ready to fall for takes that insist people are being driven insane by housing scarcity. As far as I can tell, though, homeowners are really fired-up about affordability too. What’s more, spot rents have been falling for the past three months, but people are still worried about affordability because overall inflation keeps going up.

Affordability is just nominal prices

This is, I think, the bad news for Donald Trump.

Inflation clearly made voters furious. But over the course of 2023 and 2024, the inflation rate came down and voters did not abandon their fury.

As much as Biden administration officials wanted to declare victory, conservatives would just hector them that sure, the rate of price increases has fallen, but what people want is for the price of bread to return to what they recall as a reasonable level.

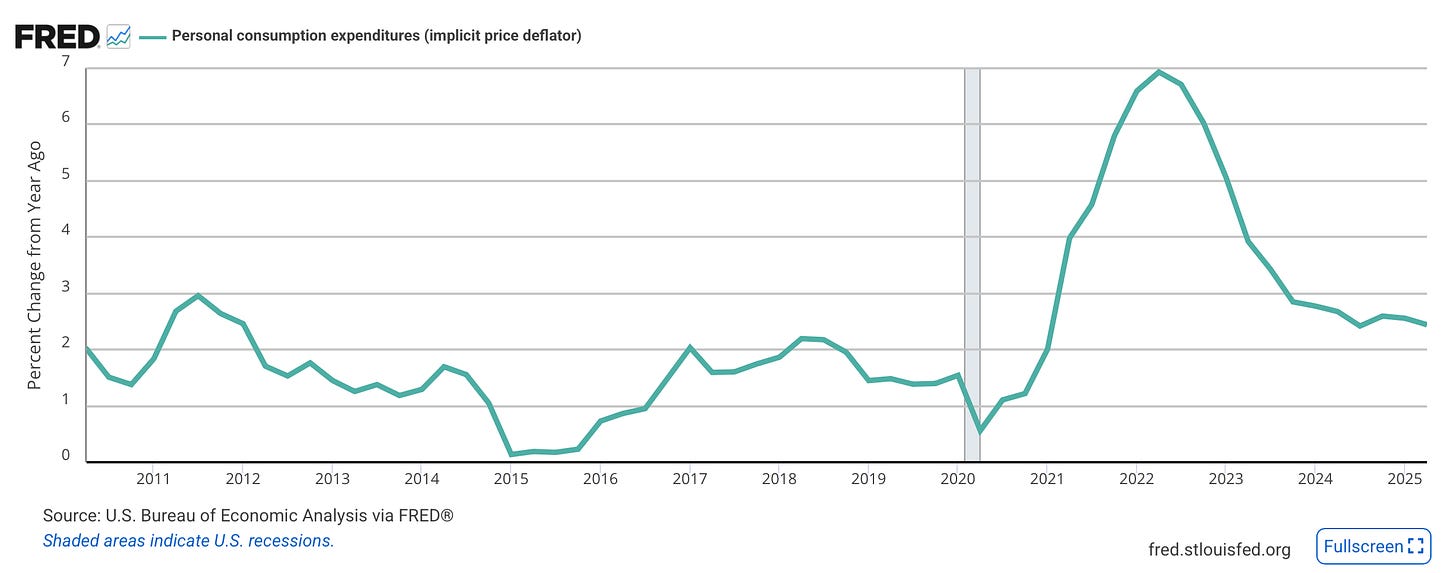

Us liberals would then reply that the only way to engineer an absolute fall in the price level would be to have a huge economy-killing recession. Trump, though, is a good popularist, and he promised people that prices would go down. But prices have not gone down! In fact, while the rate of inflation hasn’t been particularly high this year, it has been above the Federal Reserve’s official 2 percent target. You can see that in the data below: inflation has cooled from its 2022 peak but is still running above the Fed’s goal.

Between the second quarter of 2012 and the second quarter of 2021, we had a nine year run in which inflation never got as high as it has been in Trump’s second term. And if anything, it’s been ticking up higher over the past few months.

This is a tough problem for Trump to acknowledge, because the conventional recipe for inflation that’s too high would be interest rate increases. The Fed, for reasons that slightly mystify me, has been cutting interest rates, even with inflation above target, and Trump has been pressuring them to continue sending rates down. That’s understandable. One big reason why consumers remained grumpy as inflation fell under Biden is that interest rates were much higher and the cost of money is part of the cost of living. But Trump is now taking the other side of that tradeoff where interest rates fall but inflation isn’t moderating anymore, and inflation expectations are now higher than they were a year ago.

I think Trump is honestly just kind of screwed here.

Voters want prices to fall, which is what he promised, but that’s not something he could accomplish without creating an economic disaster. If the inflation rate falls a little bit more, and interest rates also fall, and then inflation and interest rates stay low for years, there would probably be a forgetting process where eventually people go back to not thinking about inflation anymore. But that could take years.

Meanwhile, the only way to push inflation and interest rates down simultaneously is fiscal austerity, which nobody wants to do. Being forced by the Supreme Court to cut tariffs would help to some extent by making certain things cheaper, but the larger deficit would itself put upward pressure on interest rates. What’s needed is a statesmanlike bipartisan fiscal compact, but does that sound like something Trump could pull off?

Just try to make good policy

Once you realize that the “affordability crisis” is basically just anger at inflation, I think you see that while Democrats should definitely talk obsessively about their ideas for promoting affordability, they should also be a little bit cautious in their actual policymaking.

It’s well known in the economics and political literature that voters are averse to inflation, even if nominal incomes rise faster than nominal prices. This is not rational, but it is very real. If your income goes up, you attribute that to your own efforts, while if prices go up, you blame someone else. The fact that this is all part of one big connected macroeconomic system doesn’t really occur to people.

And the money illusion really is blinding. I almost tweeted last weekend about how annoying it was that movie tickets are so much more expensive than they were pre-pandemic, even though moviegoing has become less popular. But I stopped myself and checked and it turns out that movie tickets are in fact cheaper in real terms than they were before the pandemic. And because incomes have risen in real terms, that means going to the movies is more affordable than ever.

The simple fact, though, is that my lizard brain remembers how much a movie ticket “should” cost and does not instinctively run through all this math.

This is all just to say that if you’re a newly elected governor or mayor, and you’re determined to address a problem called “affordability,” there’s a risk that you’re going to end up making some unsound moves while chasing a mirage. Which is not to say that you should ignore people’s material problems.

But just think concretely:

You can make your constituents’ wages and other earnings higher.

You can reduce wasteful spending and make their taxes lower.

You can use redistributive taxation and spending to boost their incomes above their market earnings.

You can eliminate regulations whose costs exceed their benefits to improve economic growth.

These are all things that would be great to do in 2025. They also would have been great to do in 2015 or 2005 or 1975. It’s always a good day to make good economic policy!

But people are still going to feel that life isn’t as “affordable” as it should be until macroeconomic inflation concerns are in the rearview, either because a long span of low inflation makes people forget or because a recession gives them something new to worry about.

This is a big political problem for Donald Trump, and I think the Fed really should be less complacent about the inflation situation. But it’s not really a policy problem that’s distinct from “overall inflation is too high,” in part because it’s not actually true that people are less able to afford things than they were in the past. Real incomes are higher, not lower, than they were before.

It’s true, of course, that real wages were very high in the middle of the pandemic, but that’s a compositional effect driven by the fact that so many low-wage service workers lost their jobs temporarily.

Ok, real median household income might have reached an all-time high. But what the author has failed to note is the amount of Americans living paycheck to paycheck.

If demanding that your unemployed friends spend $800 on your bachelorette party weekend is now considered to be OK, then things are somehow even worse than I thought they were.