A warning sign for America about Trump’s personalist rule

Why and when do autocracies underperform on growth?

If you look around the world today, the richest countries are mostly democracies. What’s more, the exceptions tend to be quite small and (except for Singapore) heavily reliant on natural resource exports. Large, complex modern economies tend to be democratic.

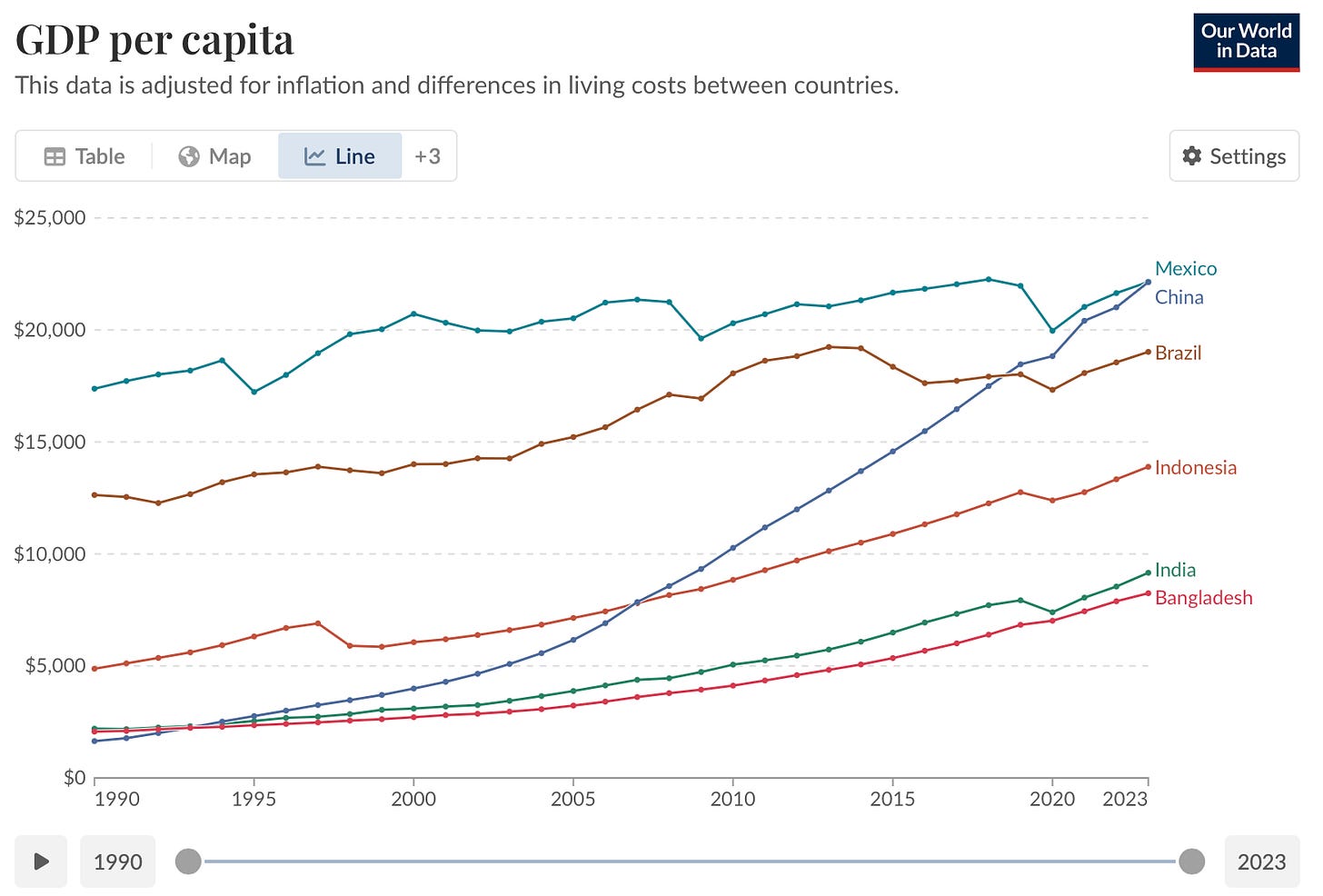

Twenty-five years ago, this pattern was even more marked. The gap in living standards between Europe and Japan on the one hand and China on the other was much larger. By the same token, the relative economic performance of various middle income Latin American countries with flawed but meaningful democratic institutions looked more impressive back then.

Naturally, political scientists tried to explain this correlation between prosperity and admirable political institutions.

One line of thought was that residents of prosperous, modern societies demanded political freedom and representation. A nation of peasants might be kept in a state of political backwardness, but an advanced economy required an educated population, a skilled mass workforce, and a cohort of middle class professionals — none of whom would stand for living under autocratic conditions. Battles for political freedom wouldn’t necessarily succeed, but continually squelching these efforts would leave a society essentially stuck.

The democratization of South Korea and Taiwan midway through their surging economic successes seemed to fit this model, and you could argue that the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe did as well. Countries like the U.S.S.R. and East Germany weren’t huge economic success stories, but they were far from the poorest countries in the world. To achieve what they achieved, they needed scientists and engineers and skilled tradespeople — people who eventually rebelled against repressive politics.

Another line of inquiry looked at this the other way around: Economic success required secure property rights, freedom of contract, and the ability of inventors and entrepreneurs to put powerful incumbents out of business. This doesn’t necessarily mean a totally laissez-faire market economy, but it does involve the rule of law and an independent judiciary and other liberal institutions. This account aligned with the historical development of the West, where the rule of law and open liberal politics preceded electoral democracy in the Anglophone and Nordic countries and, over time, led to both prosperity and democracy.

Unfortunately, the last 25 years have cast serious doubt on the theory that democracy and growth necessarily go together. China has zipped ahead of countries with considerably more democratic political systems in a way that makes it harder to dismiss Singapore or the Gulf monarchies as weird stuff happening in small countries.

A new account from Christopher Blattman, Scott Gehlbach, and Zeyang Yu suggests that regime type does matter for economic growth, but what matters is not democracy but institutionalization.

The regimes that suffer a growth penalty aren’t simply autocracies, they are “personalist” regimes in which “rule is characterized by the consolidation of power and decision-making in a small group of elite decision-makers, often organized around a single person.” They suggest that the People’s Republic of China is likely becoming more personalistic in recent years in ways that may hurt the country’s economic performance.

But it’s hard for me to think about personalistic rule without thinking about Donald Trump.

The mistake of the century

This is not the focus of the paper, but I think understanding the sincere climate of optimism around the link between democracy and economic growth that prevailed in the 1990s and early 2000s is critical to understanding contemporary American politics.

At the dawn of the 21st century, there was a lot of disagreement over the United States’ decision to grant China preferential trade status, known as “permanent normal trade relations” or PNTR, and welcome them into the World Trade Organization. Environmentalists forecasted (inaccurately) that lowering trade barriers would generate a “race to the bottom” on air and water quality rules. Labor interests forecasted (completely accurately, as it turns out) that lowering trade barriers would be bad for some of their specific unionized plants and the people who worked in them. And people like Donald Trump were throwing around all kinds of weird ideas about the economics of international trade. They weren’t concerned that allowing foreign mufflers, for example, into the country would be bad for the guys who work at the muffler factory down the street, but that somehow the existence per se of a trade deficit is a disaster for the country.

On the other side, people who understood economics correctly understood that even though freer trade with China would be bad for some Americans, it would be good for Americans on average. But these people generally believed some combination of the following:

Increased trade between the U.S. and China would facilitate a peaceful U.S.-China relationship.

Increased trade between the U.S. and China would make human rights and democracy more likely to prevail in China.

Increased prosperity in China would entail Chinese democratization, either because they couldn’t grow without more freedom or because more prosperity would lead to more demands for freedom.

Some people who were around for this political fight and were on the anti-PNTR side swear that all this optimism was bad faith through and through and just a cover for business interests.

My perspective as a college student at the time was that the optimism was completely sincere. It’s not that literally every single person believed in a strong mechanical link between prosperity and democracy. But it was an incredibly mainstream intellectual view at the time, upheld by lots of academics and scholars as well as pundits and policy entrepreneurs. Very few people understood that the then-new internet could be effectively firewalled and censored, becoming a mechanism for surveillance and social control rather than liberation.

Though it reflected widely held conventional wisdom, this was an enormous miscalculation by the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, that was then exacerbated by years of strategic distraction by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Notably, though, it was not a miscalculation about the theory of comparative advantage or the economics of tariffs. The problem with the U.S.-China economic relationship is that even though trade is win-win, geopolitical rivalry has a strong zero-sum element to it and the balance of power has been shifting toward China without their political system becoming any more admirable.

But the backlash to this miscalculation empowered people like Trump and a broad ideological horseshoe of people skeptical of conventional economics. And yet the mistake wasn’t about the economics of trade at all; it was about international relations and the domestic politics of China.

The personalist penalty

Beyond the specifics of the China case, the authors of the paper tell us that there’s no clear evidence that autocratic regimes suffer a growth penalty.

Note that the researchers specifically test the hypothesis that democracy causes better economic growth. And one reason that autocracy scores fine on growth metrics is that several countries that are currently prosperous and currently democratic were, in fact, autocratic during their periods of most rapid growth.

But they also show that if you split the autocratic regimes into two buckets, one institutionalized and the other personalistic, the personalistic regimes do meaningfully worse.

What’s the distinction? Perhaps the quintessential institutionalized autocracy was the Institutional Revolutionary Party (P.R.I. in its Spanish acronym) dictatorship that held sway over Mexico for most of the 20th century. One key attribute of the PRI regime is that its presidents observed strict term limits, and each served for a single six-year term. The president of the United States is term limited in large part to prevent a president from becoming a dictator. Mexico was undemocratic for most of this period, but the term limit meant that even in the context of an autocratic regime, the president wasn’t really a dictator. The elections were rigged, but as a decision-maker, the president had to consult with colleagues and consider a range of stakeholders.

At the other end of the spectrum was Iraq under Saddam Hussein. In the later years, nobody could fully articulate Ba’ath Party ideology — the party really was primarily a vehicle for Saddam’s control over the country. His sons Uday and Qusay occupied top positions in the regime, and a huge share of other key leaders were all from Tikrit, so much so that in 1977 Saddam banned the use of surnames in Iraq to obscure the extent to which the regime was packed with dudes named al-Tikriti. In that kind of regime, the government is not “open to talent” and lots of state institutions are structured around the idea of coup-proofing rather than doing their jobs competently.

The post-Mao P.R.C., in this schema, codes as institutionalized.

Deng Xiaoping led a regime that had meaningful collective elements. He stepped away from leadership while still alive, handing power not to a close relative but to Jiang Zemin, who passed the baton to Hu Jintao, who passed to Xi Jinping. This is a P.R.I.-like system with a top guy, but no cult of personality or unlimited authority for the leader. Except that Xi seems to be breaking the institutionalization, scrapping term limits and declining to name a successor.

Your own personal MAGA

Four years ago I would have told you that, for roughly these reasons, China was set to stumble. The U.S. led the world out of the Covid-19 pandemic by developing state-of-the-art mRNA vaccines, while China was stuck in a zero Covid policy paradigm with no way out. It seemed like one of the classic failure modes of a personalistic regime — nobody wants to tell the boss that he’s making bad decisions, so he doesn’t actually know that he’s making bad decisions, so he has no opportunity to change course. And in a bigger sense, even though everyone who’s anyone had been saying for years that China needed to come up with some new growth ideas beyond exporting manufactured goods, Xi kept not doing it.

Now I’m less sure. China, despite stumbles, just keeps being surprisingly impressive.

Suddenly developing a globally competitive automobile industry is not transcending the export-led growth paradigm, but it also shows that strategy had more running room than the skeptics allowed.

It’s particularly striking that China is on the leading edge of electric cars specifically, because this is not copying foreign technology and winning based on low wages. China leads the world in both making and deploying solar panels and batteries, both for EVs and grid storage, but also for a wide range of drones. Obviously there are still many ways things could go wrong, but I’ve been listening to well-informed China watchers predict an economic crisis there since at least 2009.

Meanwhile, here in America, Trump keeps talking about running for a third term.

He’s also taken advantage of the conservative legal movement’s longstanding advocacy for “unitary executive” theory to dispense with the idea that American institutions exist separately from the whims of the president.

Whether it’s the F.B.I. or the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, every single executive branch official is merely an extension of Trump. And he exerts personalistic control over the Republican Party like nobody we’ve ever seen in American politics. China hawks wanted export controls on advanced Nvidia chips; Nvidia wanted to sell powerful chips to a large market. Trump announced that Nvidia can sell the chips, if they pay a 15 percent fee to the U.S. government. But we don’t see G.O.P. China hawks denouncing this as a sellout of national security or G.O.P. free marketers denouncing this as a pretextual shakedown.

Trump is shutting down renewables deployment, and all we get from even senior G.O.P. members from wind-oriented states is passive-aggressive complaints, no actual effort to oppose him.

Of course the U.S. remains more democratic than China or P.R.I. Mexico or any of the other autocratic states, whether personalist or institutionalized.

But we are living through a pretty extraordinary de-institutionalization of American politics, driven exclusively by Trump and the G.O.P. His ability to completely cow intra-party opposition gives him remarkable scope to get away with corruption and remarkable tactical flexibility in addressing difficult policy questions. But it’s also eating away at some of the fundamental wellsprings of American prosperity. And in things like firing the head of the B.L.S. we see the rapid emergence of bad epistemic habits, like killing the messenger.

Maybe it’s all fine. China, as I say, continues to hold up better than I might have thought as it descends into personalism instead of moving toward the democracy we once hoped for. Maybe the country will hold up and defy the patterns of history, and maybe a totally MAGA-fied America will be okay too. But I’m awfully uncomfortable banking on it.

I still do not understand the mechanisms by which Trump imposes his control on other actors in the Republican Party. What are these people afraid of?

Is it simply that he'll speak ill of you? Write an all-caps tweet? That he'll support a primary opponent? Those don't seem sufficient to explain the Kadavergehorsam of the Republican political class.

I have always found it baffling that people admire him, think he is a good person, smart, witty, charismatic etc.. But now I'm talking about a different issue: why do they obey him? Saddam had secret police who would simply torture and kill you and your family -- okay, no mystery why people obeyed him. Does Trump have a squad of assassins? Did he when he was out of office? And who have been their victims?

The complete moral collapse of the Republican political elite is a mystery to me.

I would love to read a close chronology of the weeks after Jan. 6. The Republican Senate and House came as close to breaking with him on Jan. 7 as they ever have since 2015. But somehow, within a week, he brought them back under his will. What exactly happened? Death threats from constituents? Death threats from Trump? Blackmail on an industrial scale? What happened to Mitch? What happened to Lindsey? They came so close to getting the monkey off their backs, and then suddenly he was on top again.

Meanwhile, if you stroll over to the free speech crowd, they seem to be throwing their shoulders out for how aggressively they’re shrugging at this consolidation of personal rule.

Like, it can be true both that progressive-institutional overreach paved the way for this *and* that there’s currently an unprecedented concentration of power in one man that’s very, very bad. But audience capture, etc.

Edit: I basically mean TFP and Taibbi. I guess Greenwald, too, but I’m not sure his schtick was ever really “free speech” as such - more anti-corporate, anti-surveillance state. Not sure what he’s been up to, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he too is misplacing his skepticism of state censorship and surveillance at the moment.