Where have all the deficit hawks gone?

The consensus 10 years ago was dead wrong, but it’s the right inflation fix now

Ten years ago, the United States was in the grips of a broad obsession with the federal budget deficit.

A lot of people, then and now, have attributed this obsession to bad faith and opportunism on the part of Barack Obama’s political enemies. And it’s certainly hard to explain it in terms of the macroeconomic fundamentals — unemployment was very high, even though the economy had returned to growth after the Great Recession, and inflation was pretty persistently low, especially “core” inflation that strips out volatile commodity prices. Beyond that, interest rates were extremely low; so low that even with low inflation, the government’s borrowing costs were typically less than the rate of inflation.

But I don’t think it really was bad faith.

For starters, a decent amount of the miscalculation was coming from inside the house, with the president himself talking about deficit reduction as soon as October 2009. And I think that’s because going back to the 2004-2007 period before the Great Recession, most of the leading figures of the Democratic Party were very hung up on criticizing George W Bush’s deficits. The situation Obama inherited in 2009 was very different from the one he described back in his 2006 talk at the launch of the Hamilton Project. But the 2006-vintage concerns remained influential on the thinking of his team.

But the other reason I don’t think it was total bad faith is that in 2012, Mitt Romney was perfectly happy to hurt himself politically for the sake of deficit fastidiousness. Instead of promising the kind of debt-financed tax cut that Bush and Ronald Reagan (and later Donald Trump) delivered, he felt he needed offsets, which led to him embracing toxically unpopular ideas to raise middle-class taxes and cut Medicare. The whole country could have been on a very different trajectory if the debate 10 years ago was about which mix of tax cuts and spending hikes would optimally boost the economy rather than about Simpson-Bowles, the “super committee,” sequestration, and the search for a grand bargain.

Weirdly, though, here we are in 2022 with unemployment low, inflation high, and interest rates rising fast, and nobody is talking about this anymore.

Not literally zero people — the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget recently released a good paper called “Fiscal Policy in a Time of High Inflation.” But that’s a monoline deficit reduction group, and it didn’t get much attention. A decade ago when deficit reduction didn’t make a lot of sense, everyone and his mother was producing deficit reduction plans, and mainstream economic policy coverage would’ve been all over something like a fresh CRFB report. So I’m going to be the change: this would be a good time for deficit reduction.

Inflation — a top-down view

One way of measuring inflation is to copy the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ methods and calculate it using a bottom-up analysis, adding up the prices of the individual components of the index. At any given time, some prices will go up more than average and others less so. You can try to look and see if there’s some particular reason that Category X is spiking so much, and there usually will be one. After all, absent some kind of bottleneck, higher demand would lead to higher output rather than higher prices.

These analyses tell us a lot about what’s happening in the economy, but I think that since the vaccine rollout of early 2021, they have consistently proven to be a poor guide to the future of inflation.

It might be true that at some specific time the inflation is concentrated in cars (chip bottleneck) and services highly impacted by the reopening (hotels, airfare), but when those bottlenecks resolve, new inflation pops up somewhere else. And that’s the power of top-down analysis. A spending volume increase flushing through the economy can accomplish great things in a recession — idle resources like unemployed workers, shuttered factories, and empty storefronts are mobilized to meet the new, higher level of demand. But extra spending flushing through an economy that doesn’t have a ton of idle resources can result in higher prices. When price weirdness in one area abates, that frees up extra money for something else. At the moment, it seems that after a lot of bouncing around from one category to another, inflation is settling into rents. The housing supply couldn’t expand as fast as people’s spending, so rents spiked. I think the doves are probably right that rent inflation will settle down soon. But a top-down view says that just means the inflation will pop up somewhere else.

I am all for supply-side measures, because supply-side measures generate growth in an economy that isn’t demand-constrained. But in terms of inflation per se, the top-down view predicts much better, and it’s why I’ve supported the Fed’s moves to raise interest rates.

What’s surprised me is that I expected sharp interest rate increases to slow inflation very quickly by operating through expectations. I thought we’d see a big, rapid impact on stock and bond markets, which happened. And I thought that would rapidly pass through into the wage- and price-setting decisions of other economic actors, which has so far not happened. So why, despite the clear expectations of a slowdown — including very restrained market-based measures of inflation expectations — do prices keep rising?

Extra money everywhere

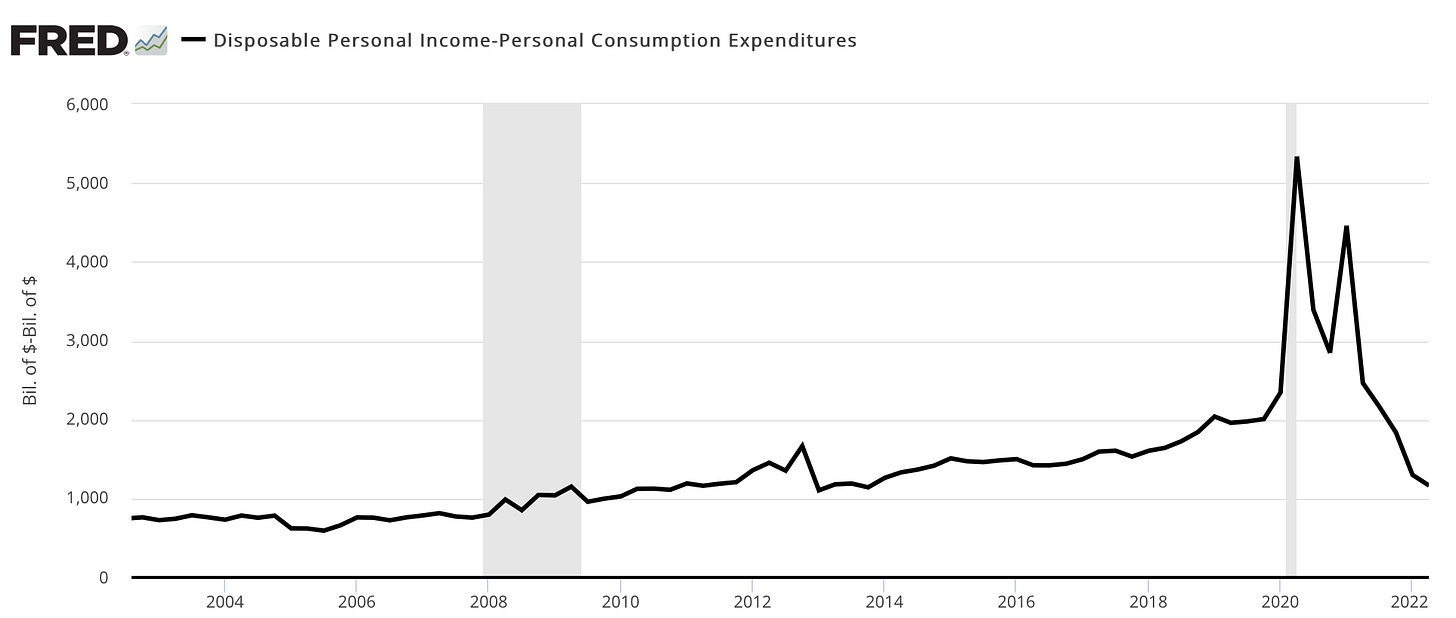

A perhaps underrated way of looking at this is offered by this Joseph Politano chart of household income and consumption spending dynamics. You can see that during the pandemic, consumption went way down, but incomes soared due to the multiple rounds of stimulus.

When the pandemic started, I expected consumption to crash — particularly on things like meals, entertainment, and travel. And I thought that would happen even in places that didn’t adopt a lot of formal restrictions. If a large minority of the population stays home all the time, while most people cut back their activities only modestly, that still adds up to a huge aggregate crash in spending. That fallback in spending was going to lead to huge losses of income as lots of waiters, pilots, and hotel managers got laid off. But then all of those people would need to reduce their spending on not just restaurant meals, but on furniture and clothing and other basic stuff.

We were, I thought, looking at a broad economic unraveling. At Vox, the ad sales market essentially vanished overnight. The company panicked and the union reached a deal to avoid layoffs by suspending 401(k) matches and temporarily cutting the salaries of higher-paid employees like me.

But this turned out not to be the story of the pandemic. There were a lot of pandemic layoffs, but they were limited to the directly impacted sectors. Thanks to the stimulus bills, most people’s nominal incomes ended up higher than they were pre-pandemic. There were exceptions to that rule, including people who fell through the cracks of the welfare state as well as weird edge cases like me.1 But in the aggregate, the stimulus measures not only filled the holes in people's pockets — they absolutely stuffed them.

This, as designed, prevented the supply shock of the pandemic from turning into a spiraling demand shock. The economy recovered quickly as things reopened and as the moderately cautious got vaccinated, and it was basically an economic success story. That led to some reopening inflation that was annoying, but had it actually been transitory, I think a post-reopening burst of inflation wouldn’t have been a real problem. But it hasn’t been transitory, it’s been persistent. And it’s persisted even in the face of clear disinflationary signals from the Fed.

The Fed’s response is going to be to keep raising interest rates because that’s the tool they have. But look again at income and spending. This is a chart of nominal disposable personal income (ie. after taxes) minus nominal personal consumption spending. You can see that it has soared way above trend for two whole years and has now fallen below trend as people spend down their accumulated savings.

This behavior has been a little surprising to me. I thought a lot of Americans would balk at paying high prices for discretionary items (everything from video game systems to furniture, restaurant meals, vacations, and all the other stuff we buy but don’t really need) and would simply use their pandemic excess to shore up their personal finances. You’re always reading about how people aren’t saving enough for retirement, so why not use the pandemic savings burst to adjust that? But apparently that’s not how people think. People are now spending more than they earn and covering the gap with the lagged proceeds of emergency payments. It’s the clearest evidence that the American Rescue Plan was poorly designed and should have featured longer-term investments and less short-term spending.

Accumulated savings also helps explain two things. The Fed is struggling to slow excess consumption because it’s being funded out of money that people already have. And long-term expectations remain tame not only because the Fed is credible but because people are going to run out of this money sooner or later.

But for now, inflation is not just a little bit above target. It’s way above target, so the Fed is likely going to want to raise interest rates a lot. That not only raises the prospect of job losses and unemployment, but even if it’s executed as an extremely artful soft landing, it would hurt the investment side of the economy and therefore the economy’s long-term growth potential.

But we could minimize those harms with an idea straight out of 2012: deficit reduction.

Fiscal policy can target the pain

The key advantage of fiscal policy as a complement to monetary policy in this situation is that you can try to use fiscal policy to drain the wallets of those who can most afford it, rather than hammering interest-sensitive sectors willy-nilly.

That means, basically, affluent people. But since we are specifically trying to curb consumption, it needs to be affluent people broadly construed, not a tiny number of super-rich billionaires. That was the big problem with student loan relief — even with a means test, a decent share of the benefits flowed to people in the top half of the income distribution, when those are precisely the people whose money we need to be taking away.

The other thing I’d note is that oftentimes Republicans put forward entitlement reform plans that cut Social Security and Medicare, but then to avoid scaring elderly people, they delay the implementation of any cuts for 10 years or more. I get the game they are trying to play politically, but long-term deficit reduction doesn’t do anything to address inflation. You want fiscal measures that target a large swathe of people with above-average incomes and that target them relatively quickly.

On the tax side, another idea is to cap deductions. Right now, not only does the federal government make a lot of tax deductions available, but due to the progressive rate structure of the tax code a deduction is worth a lot more to a person earning $700,000 a year than to a person earning $75,000. You could cap all deductions at the 22 percent bracket (that’s $40,526 to $86,375 in income for a single filer) and say that richer people in higher brackets can’t get the full value of the deductions. On spending, Social Security beneficiaries are set to get the largest cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) on record to help cope with inflation. That’s nice for them, but it drives further inflation. Maybe people in the top third of the benefits distribution don’t need that full COLA? Retired people consume a very large share of their income, and making the richest swathe of retired people restrain themselves a bit could help cool inflation a lot.

Even deeper in the wonky weeds, there is the question of Medicare reimbursement rates and Medicare Advantage premiums. Squeezing both of these factors gently has an outsized impact on inflation, not only because it somewhat drains the pockets of medical providers, but because Medicare pricing directly impacts pricing in the private side of the health care system (let’s pair it with increasing the supply of doctors).

Now of course, as long as you’re talking about deficit reduction, it also might make sense to talk about long-run fiscal balance. I was saying over the summer that the Biden Administration should look at appointing some boring bipartisan commissions, with long-term deficit reduction as the big daddy of boring bipartisan commissions. Progressives have developed a kind of allergy to this subject both because they (rightly!) are annoyed that the deficit mania of 10 years ago hurt the economy, and also because it runs counter to their ambition for a dramatic expansion of the welfare state. But today’s situation is not the situation of 10 years ago, and at the moment there is no short-term path to dramatic expansion of the welfare state. Just because deficit hawks were wrong in the past doesn’t mean they are wrong now, and while the Fed almost certainly can cool the economy purely with interest rate hikes, that’s not the best way to do it. Americans have tons of extra money sloshing around, fueling continued spending and inflation. Some of those Americans are relatively well-off, and we should be targeting them with fiscal policy.

Vox cut my pay, but my prior year’s income had been too high to qualify for stimmies — we did get SNAP benefits because our kid attends a universal free lunch school.

I agree completely with the analysis. But there is exactly zero chance that any of this will happen, right?

Let us remember that it was very recently that Biden decided to do student loan forgiveness, which is the worst possible policy in current economic conditions (increases deficit, increases spending, bad distributional effects, no long term structural benefit).

He seems incapable of doing anything even remotely unpopular, and what Matt proposes would be *very* unpopular.

While I agree that now would actually be an appropriate time for austerity policies, I don’t think the politics will work out. Any policy that seeks to decrease the consumption of a significant enough portion of the electorate to affect inflation is going to be politically toxic. Just look at how we can’t even contemplate increasing taxes on anyone earning less than $400k/year.

I don’t think it matters what combination of tax increases and benefit decreases compose such an austerity policy. The simple fact that a non-trivial number of voters will see a proposal to decrease their spending power will lead to massive political blowback. I just don’t see how any politician could propose or support such a proposal without consigning themselves to future electoral defeat.

Although I do see some potential if there is some sort of external force constraining our options. For example, the new UK government has been forced into a U-turn when their hastily developed tax cuts and financial support for household energy bills led to turmoil in their government bond market as well as a rapid depreciation of their currency.

I guess something similar could happen in the US. My understanding is that a lot of the 90s concern about deficit was focused on “bond vigilantes” causing financial turmoil if investors lost faith in US government debt. E.g., Carville’s famous quote about wanting to be reincarnated as the bond market because, “You can intimidate everybody”.