What true political leadership looks like

Sarah McBride's slow boring of hard boards

Before we begin, I want to remind everyone that in accordance with our policy that comments must be civil and constructive, anyone who misgenders Congresswoman McBride or Chase Strangio will get an automatic 24-hour ban.

I heard Sarah McBride speak off the record this spring, and I thought she was deeply impressive and thoughtful and wished that I could quote her. And then lo and behold, she went on the Ezra Klein show and made similar remarks.

As with any politician, I don’t agree with every single thing she says. But I think her perspective on the nature of social change and the purpose of electoral politics is correct and insightful. And I think this below is the money quote, making the point that the great heroes of the past were, in fact, pretty pragmatic and willing to go to great lengths to score incremental victories:

“You can’t compromise on civil rights” is a great tweet. But tell me: Which civil rights act delivered all progress and all civil rights for people of color in this country? The Civil Rights Act of 1957? The Civil Rights Act of 1960? The Civil Rights Act of 1964? The Voting Rights Act of 1965? The Civil Rights Act of 1968? Or any of the civil rights acts that have been passed since the 1960s? That movement was disciplined, it was strategic, it picked its battles, it picked its fights, and it compromised to move the ball forward. And right now, that compromise would be deemed unprincipled, weak, and throwing everyone under the bus.

I think the key point is that successful political movements do cater to public opinion and make an effort to be seen as reasonable in the eyes of most people. If you’ve read Nicholas Confessore’s profile of the ACLU’s unsuccessful litigation strategy around trans issues, you’ll meet Chase Strangio, who led the charge and is completely dismissive of the kind of strategic action McBride discusses. And as Confessore details, that approach ended in disaster.

Of course, some people were less impressed by McBride.

David Roberts, who I think pairs great, incredibly informative work about the details of energy policy and emissions with kind of slipshod political takes, denounced her commentary as an “argument against the very idea of political leadership.”

I don’t think that’s true at all. What McBride is doing here is using her standing as a trans member of Congress from a safe seat to empower her colleagues to stand up to the most unreasonable, unpragmatic demands and rhetorical tropes of activists who’ve hurt Democrats’ electoral performance while causing public opinion to move against them on trans issues. That is political leadership.

But oftentimes what progressives mean by “political leadership” isn’t “political leaders trying to be constructive,” it’s that if politicians pound the table hard enough, they can bend public opinion in their direction. All the evidence, though, is that this probably won’t work and is instead likely to backfire.

Public opinion is a thermostat

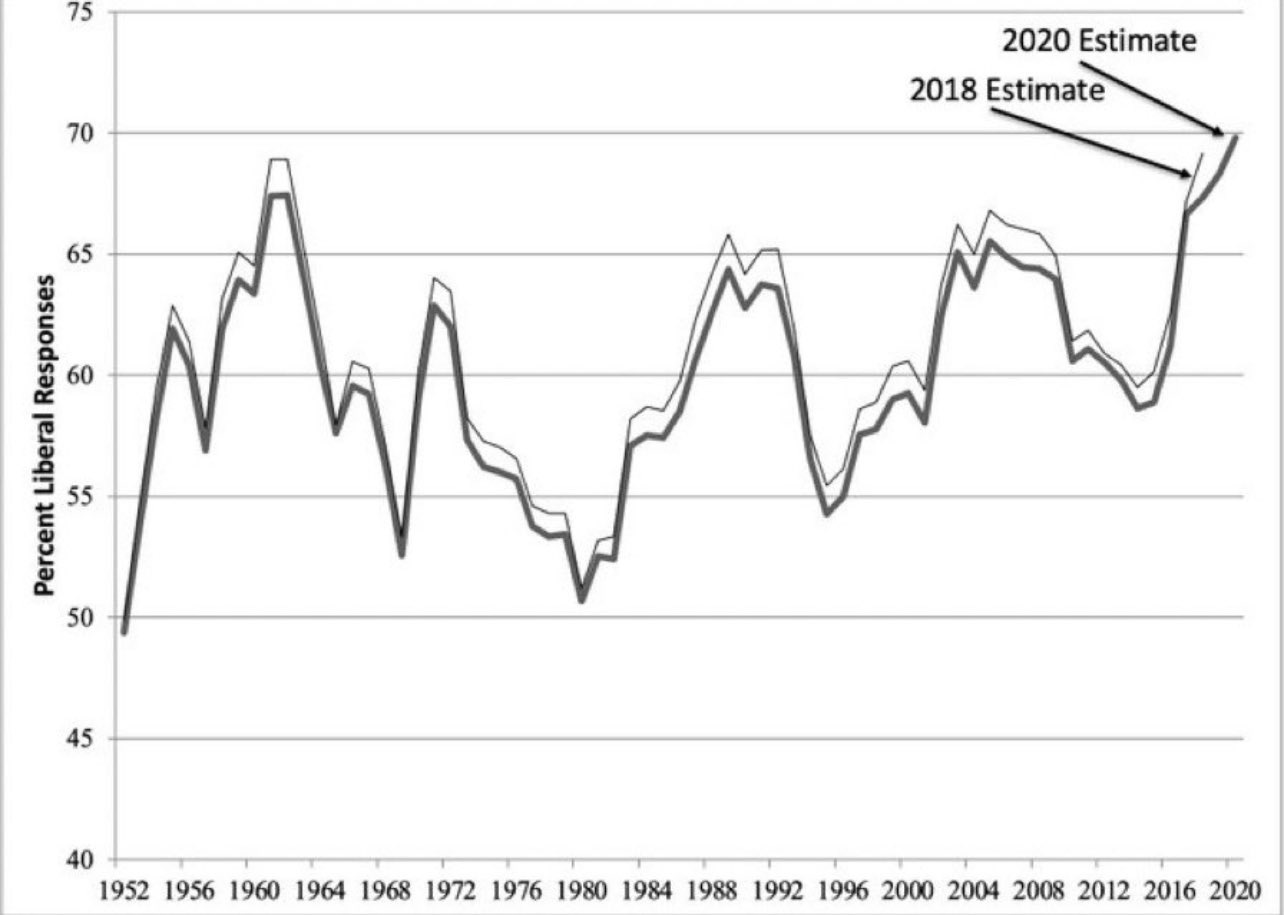

As Christopher Wlezien puts it, public opinion normally acts like a thermostat. When the temperature goes up, a thermostat turns on the air conditioning. As it gets cooler, it turns the AC off. And if it gets even colder, the thermostat switches on the heat.

In his original paper, Wlezien looked at how in the lead-up to Ronald Reagan’s election win in 1980, public opinion was swinging in favor of higher levels of defense spending. Then after Reagan won and defense spending started going up, opinion shifted in the other direction. This is a pretty common pattern. When a Democrat is in the White House, the share of the public saying the government is “doing too much” tends to rise sharply.

This is in part because Democrats believe in a more activist government and tend to have the government do more stuff.

The interesting debate here is how much the thermostat is driven by policy change versus symbolism. Ronald Reagan advocated for higher spending on the military and spending on the military went up. Obama’s first two years featured both a president who believed in activist government, and also a lot of new programmatic activism. But when federal spending was falling slightly in real terms between 2010 and 2014 as a result of House Republicans’ demands, public opinion still seemed to reflect the symbolism of a Democrat in the White House.

Similarly, the fact that spending was consistently rising during Trump’s term — even before Covid — didn’t generate anti-spending backlash. The backlash was instead against an unpopular Republican president, moving opinion in a more liberal direction. One way you can see this is that Trump was the first president in a while to clearly advocate for lower levels of immigration. And by the end of his term, for the first time on record, more people wanted immigration increased than decreased. Some moron even published a book titled “One Billion Americans” in the fall of 2020.

Then Joe Biden became president and opened his term with some flashy announcements on immigration. The number of irregular migrants surged in an unprecedented way, and public opinion made a sharp u-turn on immigration levels.

To be clear, these backlash effects are an observed regularity, not a law of physics. The people who blame demagogic entrepreneurs or the media for fanning the flames of anti-immigration sentiment during the Biden years aren’t totally wrong. If it was possible to enforce a cartel whereby nobody in politics or media would mention that immigration levels were surging, we would have seen a much more muted effect. Situations also sometimes arise like in 2004, when sentiment was pretty strongly anti-immigration, but neither party tried to take advantage of that. The decisions and actions of people in the political system make a difference; we’re not just hostages to arbitrary fate.

What we don’t often see, though, is Democratic Party politicians successfully dragging public opinion to the left through forceful advocacy. Nor are Republican Party politicians very good at dragging public opinion to the right. That’s because politicians aren’t broadly beloved figures. They mostly persuade their own core supporters. But core Republicans are already quite right-wing, and core Democrats are already progressive, so there’s relatively little juice in their advocacy.

Politicians persuade their own followers

Again, that doesn’t mean that political rhetoric is pointless.

Donald Trump supporting the CARES Act, for example, made most rank-and-file Republicans like the CARES Act and greatly muted elite Republican criticism of a massive spending bill. If Covid had hit during a Democratic trifecta, they probably would have passed something broadly similar to CARES, except the content would have been a little more left-wing, the vote would have been along party lines, and public opinion would have been much more polarized. Similarly, if Obama had managed to seal the deal on a grand bargain with Paul Ryan, he probably could have sold a hefty chunk of the Democratic base on Medicare cuts that they’d hate if proposed by a Republican. And when Trump became the leader of the Republican Party, he helped boost Medicare’s popularity with Republicans.

All of which is to say that while partisan political leadership is a real thing, it normally cuts in the opposite direction from the activist conception of it.

Of course on some issues, it’s not really clear which position is “left” and which is “right.” Here, political leadership mostly serves to polarize. Trump’s strident advocacy for tariffs has made conservatives more skeptical of free trade and liberals friendlier toward it.

But the movement here is not symmetrical. Trump is generating more backfire than support for his own position. Sometimes, polarizing opinion around an issue works out better than that. Still, the backlash risk isn’t some weird one-off — it’s an omnipresent aspect of politics.

We just got a textbook example of this with Mike Lee’s proposal to sell off a small amount of non-park federal land to facilitate housing in the Mountain West. By rolling this out without collaborating with any Western Democrats and placing it in the context of a hyper-partisan reconciliation bill, Lee supercharged Democratic opposition while still leaving plenty of Republicans hostile to the idea. I think some version of housing on federal land is a pretty good idea, and it has, in the past, garnered support from Democrats in Nevada and Arizona. But if it ever happens, it will probably happen via quiet dealmaking in Secret Congress. Having loudmouth members do “leadership” just leads to backlash.

Similarly, since the election, I’ve heard a lot from progressives about the idea that Joe Biden’s limits as a communicator are responsible for the political failure of Bidenomics.

I’m pretty skeptical.

Democrats liked Biden’s economic policy just fine, and they’re the target audience for persuasive presidential communication. If you want to see the political impact of Biden’s inability to communicate, I would look at the political reaction to his approach to Israel. A younger, more active, and more charismatic president probably would have done a better job of selling his base on the wisdom of arms sales to Israel. Progressives are a little blind to this because of course they have strong progressive convictions, so their vision of a more effective communicator is someone who would have sold the public on progressive ideas. But that’s really hard. Getting your own base to agree with you, by contrast, is pushing on an open door. Biden’s inability to do that was, in retrospect, a big tell about his diminished capabilities. But progressives would have liked him less if he’d been more effective in this regard.

Real leadership is accomplishing things

Notably, all this stuff about thermostatic backlash is true even of presidents who, in retrospect, seem like they were really successful in shifting the country. Public opinion got steadily more liberal during Ronald Reagan’s eight years in office — there was no communications magic that allowed him to defy the laws of political gravity.

The reason that Reagan is a big deal historically isn’t that his words pushed public opinion rightward, it’s that some of his policies had durable long-term impacts.

An underrated one, in my view, is that before Reagan, the thresholds for different tax brackets were specified in nominal terms. This meant that every year, there was basically an automatic tax increase. As a result, politicians never raised taxes — all they ever did was tax cuts. This made life a lot easier for proponents of high levels of government spending, because all they had to do was moderate demands for tax cutting, not affirmatively raise taxes, which, as we saw yesterday, is hard. Large swathes of the original 1981 Reagan tax cut were scaled back or revised over the years. But once tax brackets were indexed to inflation, nobody ever had the guts to un-index them.

Obama, by the same token, didn’t enduringly reshape public opinion, but he did reshape public policy. The Affordable Care Act massively reshaped how health insurance is regulated, and Trump’s first effort to repeal those rules was so toxic that eight years later, he doesn’t dare try. One of the signature gaffes of my career was Nancy Pelosi telling her colleagues, “We need to pass the bill so people can find out what’s in it.” But that’s political leadership. By voting yes on an unpopular bill, House Democrats caused the bill to become law. Many of its provisions, once in force, became popular. Not fast enough to save Democrats from a brutal 2010 midterm, but fast enough that by 2017, it couldn’t be repealed.

Similarly, after a ton of back-and-forth and handwringing, New York Democrats finally pushed an unpopular congestion pricing plan through. And it’s been working well! So far, New York seems to be having the same experience that Stockholm and London had with congestion pricing, which is that people didn’t like the idea because they didn’t believe it would work, but once it’s in force, they like it. In all these situations, there’s a serious case to be made for forging ahead with controversial or even politically toxic ideas. But it’s not a case that relies on the force of words changing people’s minds. It’s a bet that certain policies will become sticky once they’re implemented. That doesn’t mean you can just throw caution to the wind and hope for the best, though. The bet we’re talking about here is genuinely risky. If Obama had lost in 2012, the ACA wouldn’t have had time to become sticky.

And not every bold idea works out. In the 2015-2020 era, progressives forged ahead with some pretty half-baked ideas on de-policing. Crime went up, and serious backlash followed.

Betting on the merits of your ideas is reasonable. But for the bet to pay off, you do actually need good ideas, another reminder that accurate policy analysis remains an underrated political investment. Everyone wants to believe that they already have all the answers and all they need is more propaganda, but that’s rarely true. Good ideas are hard to come by. And precisely because politicians have more sway within their own coalitions than with swing voters, true political leadership often consists of being a voice for restraint and caution when the easy thing to do is go along to get along.

I’ve said this before, but I think it bears repeating: the value of Slow Boring to me has been teaching me, at a very embarrassingly late stage, that 1) empirical analysis is important and 2) politics (in a practical, not definitional sense) is negotiation, compromise, consensus-building and just generally the slow boring of hard boards.

Neither of these are revelations - but boy howdy, did I not even dimly grasp them in my younger, much dumber days when I thought “politics” was either inscrutable performative critique* or table-pounding maximalism coupled with sneering contempt for people who don’t agree with you.

* people like to blame “postmodernism” for this, and there’s some truth to it, but really it was the product of a midwit army of social science / humanities grad students (of which I was part and have endeavored to escape from) trying to clumsily apply Foucault, Derrida, “la French theory,” etc.

From my experience, in schools, it is taught that the culmination of Black civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s was the March on Washington and Martin Luther King Jr.'s speech at Lincoln Memorial. As if in some Sorkin-esque way, King's speech that day settled the Black civil rights debate forever. All the work and negotiation in Congress, LBJ, Robert Byrd, and Strom Thurmond aren't taught. And I think the way it is covered in schools makes a lot of people believe that all you have to do to win any public debate is say the correct magic words.