What to do after affirmative action

Redistribute resources away from the richest, most exclusive schools

The Supreme Court seems very likely to deal a major blow to college affirmative action programs when it rules on the Harvard v. Students for Fair Admissions case.

In the controlling precedent from Grutter v. Bollinger, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote that “race-conscious admissions policies must be limited in time … the Court expects that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.” She was writing in 2003, 19 years ago rather than 25. But at the time, Day O’Connor was the median justice. When she retired, the median justice became the more conservative Anthony Kennedy. Then when Kennedy retired, the median justice became the more-conservative-still John Roberts. And when Ruth Bader Ginsburg died, the median justice became the even-more-conservative Brett Kavanaugh. Given this substantial rightward shift, we should expect some precedents to be overturned, and since even O’Connor seemed torn on this particular question, I very much doubt that Kavanaugh is.

And the Court doesn’t need to fear backlash here. In public polling, overwhelming majorities say race should not factor into college admissions. In Blue Rose Research competitive message testing (previously seen on Slow Boring), affirmative action performs worse than cutting police funding in partisan framing and pro/con arguments.

So the question is less how will the Supreme Court rule and more how will the world react.

Most likely, elite universities will try to exploit whatever wiggle room the court leaves to backdoor as much affirmative action as they possibly can, possibly by intensifying the test-optional trend so it’s harder to quantify discrimination against Asian applicants. But the broader world should recognize that while foot-dragging on compliance will be narrowly beneficial to the most exclusive universities’ interest in preserving the status quo, there are much better ways to proceed.

The key to that, however, is to acknowledge that the top schools are bad actors, not allies, and a serious push for racial and economic justice requires redirecting material resources and social esteem away from the most selective schools and toward schools that serve worthier social purposes.

The status quo is not in line with progressive values

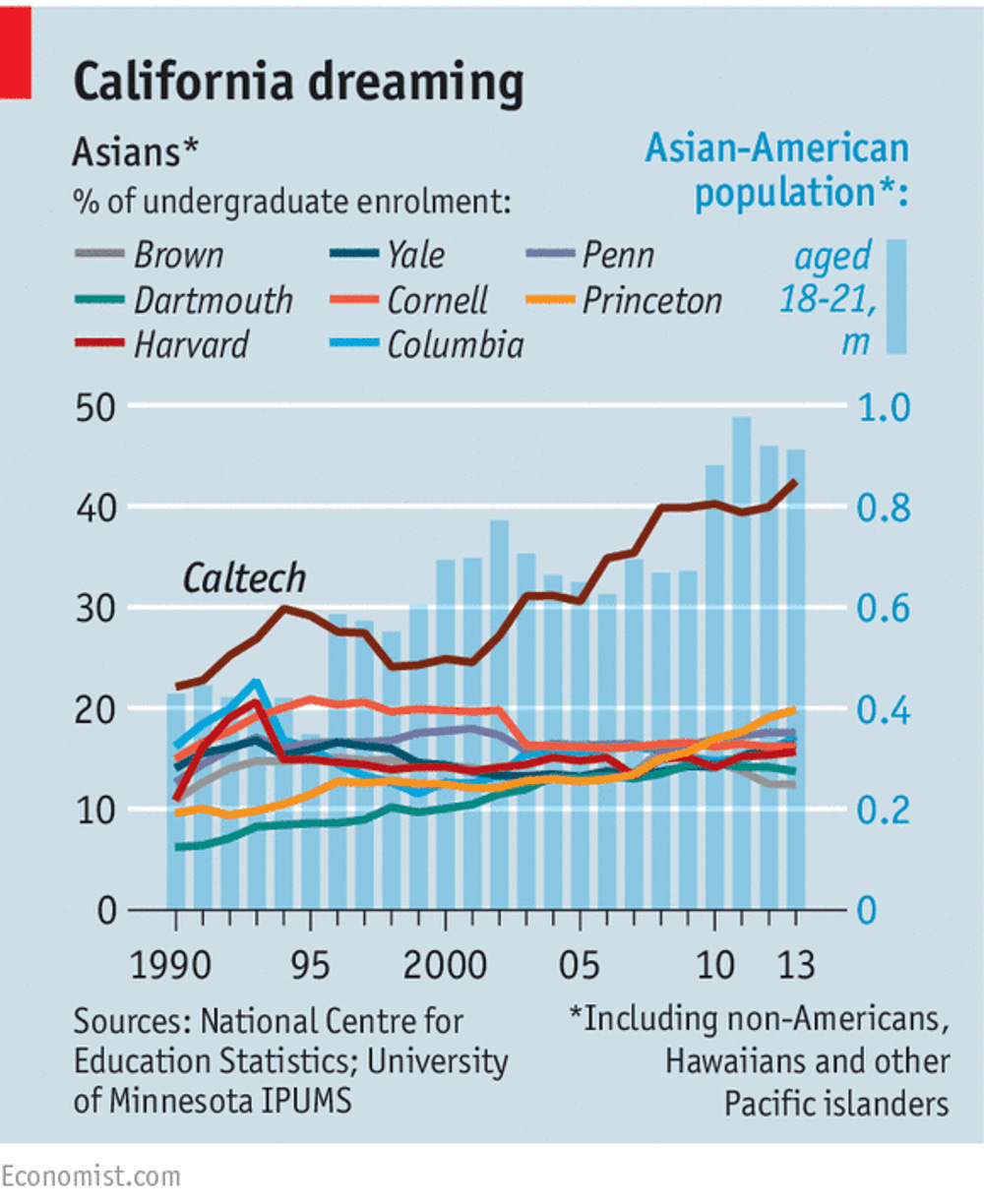

A large share of elite universities seem to be applying de facto quotas to prevent the Asian-origin share of their student body from rising in line with their share of the population. This chart from The Economist tells the story in broad terms.

Affirmative action proponents prefer to draw attention to legacy admissions, athlete preferences, and other non-academic factors that play into college admissions. But at Harvard, all of these admissions policies add up to produce a class that’s about as white as one that would come from admissions based on pure academics — just much less Asian.

But it doesn’t do much good for a white kid whose parents didn’t go to Harvard and who hasn’t had fencing lessons to know that the school loads the dice in favor of a different, richer set of white kids.

Affirmative action generates more racially balanced classes at elite universities but places the burden of adjustment on the shoulders of Asian Americans and lower-class white people rather than rich white people. Meanwhile, a person like me — a fairly privileged young person whose father’s family happens to come from Cuba — got a boost. I don’t know of any theory of distributive or restorative justice that says this is a reasonable formula for addressing America’s legacy of racial discrimination or present-day inequities. But it’s what’s actually happening.

I think Bill Clinton’s old “mend it, don’t end it” formula made a lot of sense, but in reality, nothing has been mended in the 25 years since he said that. Now the courts are poised to end it, and unfortunately, ending it could have bad consequences too.

“Mismatch theory” seems to be mostly wrong

One optimistic take on the end of affirmative action is that it will actually be good for Black and Hispanic students. The theory is that students with below-average academic preparation struggle in their classes, become demoralized, and drop out or switch to an easier major, ending up worse off than if they’d attended a less selective institution.

There is a lot of literature on this back and forth. And I think mismatch theorists have found some specific cases where the hypothesis holds. The clearest case, I think, is that affirmative action leads low-tier law schools to admit marginal Black and Latino students who have low bar exam pass rates, and in many cases, those students would have been better off not incurring law school debt.

But the mismatch hypothesis does not hold up in general.

Zachary Bleemer’s paper looking at the impact of Proposition 209 in California shows pretty clearly that, on average, the whole life trajectories of Black and Latino students took a turn for the worse as a result of attending less-selective colleges.

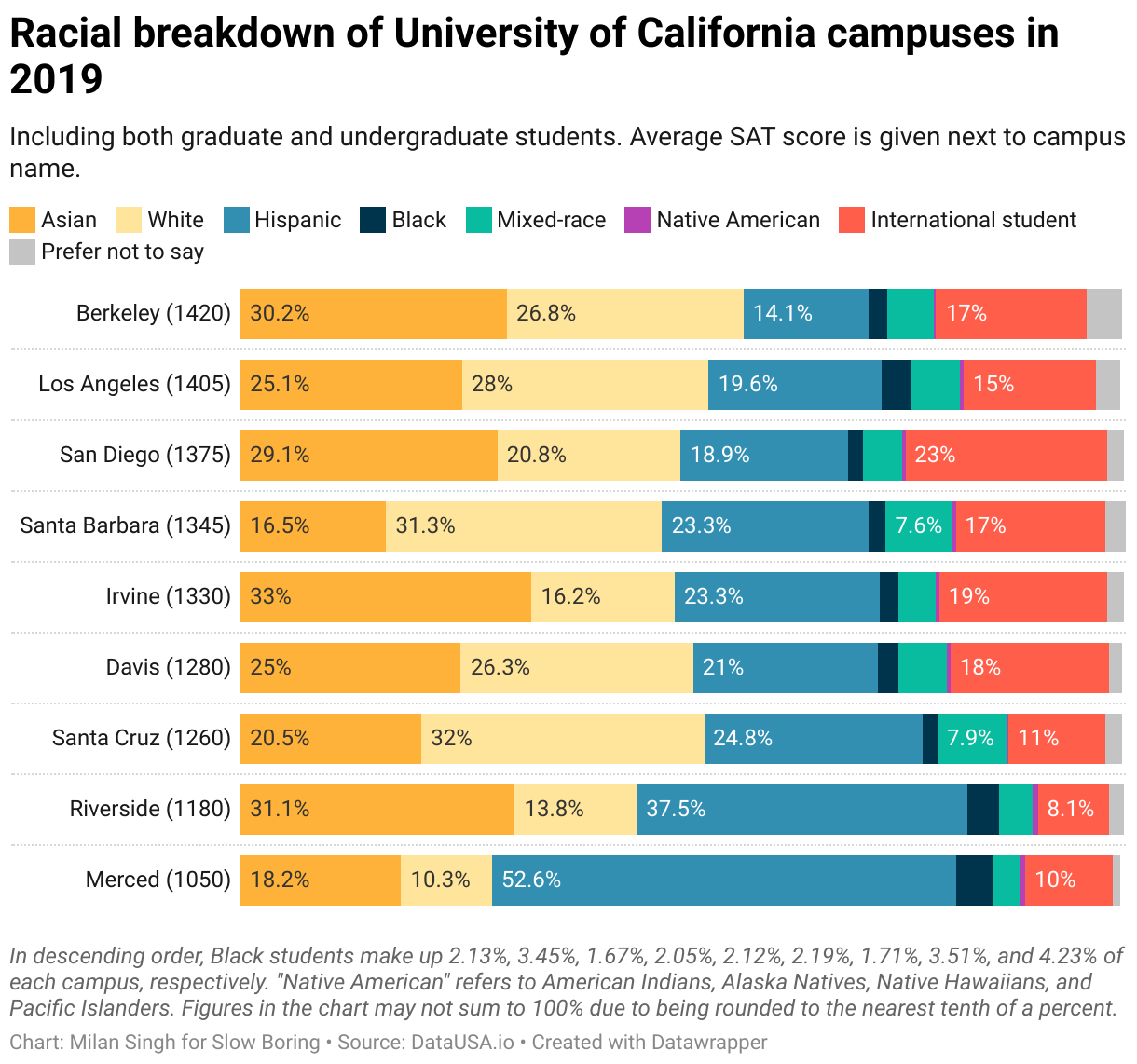

One key dynamic at work is a cascade effect. The University of California system runs a network of campuses of varying selectivity, all of which invest significant resources in their students. Prop 209 pushes some Black and Hispanic students out of more prestigious UC schools like Berkeley and toward campuses like Santa Cruz, so the schools with the highest average SAT scores (Berkeley and UCLA) have the smallest Black/Latino population share, whereas the less-selective UC Riverside and UC Merced campuses have more.

But it then also pushes lots of students who might have attended the lower-tier UC schools out of the UC system altogether. And when you drop out of the system into other schools, you’re not only talking about a different cohort of peers; you’re talking about a different level of resources dedicated to students.

To flag a point that I’ll return to later, part of the harm that Bleemer is identifying is the perversity of the American system of higher education financing — we deliver the fewest resources to the students who need the most help.

And that’s a critical point because for every student pushed down by Prop 209, there’s another student lifted up. So you could have a world of zero-sum competition between Black/Latino students and white/Asian ones. But that’s actually not what Bleemer finds. Instead, he says “complementary regression discontinuity and institutional value-added analyses suggest that affirmative action’s net educational and wage benefits for [under-represented minority] applicants exceed its net costs for on-the-margin white and Asian applicants.”

That conclusion is consistent with a bunch of other findings looking at other issues in higher education.

Top X% plans seem to work well

When Texas ended affirmative action, it implemented the “top 10%” plan, automatically admitting high school students in the top decile of their class to the University of Texas. The idea is that due to ethnic and socioeconomic segregation, this would give a leg up to some less privileged applicants who otherwise wouldn’t get in. But since it’s a non-racial criterion, it’s allowed under the terms of Texas law.

Sandra Black, Jeffrey Denning, and Jesse Rothstein looked at this and found that marginal students pulled into UT “see increases in college enrollment and graduation with some evidence of positive earnings gains 7-9 years after college.” But what about the students pushed out? Well, they “attend less selective colleges but do not see declines in overall college enrollment, graduation, or earnings.”

That is a bit of a weird finding.

But it’s strongly reminiscent of something that Alan Krueger found back in 1999 and that he and Stacy Dale confirmed in 2011: for most students, the value of attending a selective college is low.

While it’s true that graduates of the most selective schools do better than graduates of the less-selective schools, that’s at least in part because the most-selective schools are trying to admit the kids with the best odds of doing well in life. In the median case, it turns out that the higher earnings for graduates of more-selective schools are entirely explained by the selection effect with no discernible treatment by the university.

But there’s an exception: “for black and Hispanic students and for students who come from less-educated families (in terms of their parents' education), the estimates of the return to college selectivity remain large, even in models that adjust for unobserved student characteristics.”

I think these lines of research all support the same conclusion — meritocratic sorting generates an inefficient outcome because educational resources are more valuable when targeted at low-SES students than when targeted at the best students. So for public universities, I think this adds up to a strong case for using the Top X% admission system. It seems more politically stable than race-based affirmative action but produces broadly similar benefits for roughly the same reason.

Two further notes on this:

Black, Jane Arnold Lincove, Jenna Cullinane, and Rachel Veron find that Top X% does not erase inequities in high school quality and that graduates of the lower-quality high schools do worse in college with persistent effects. So it’s a good policy, but it’s not magic, and we do need to still care about K-12 school quality.

Julie Berry Cullen, Mark Long, and Randall Reback find that Top X% does induce some people to strategically sort into low-performing school districts. This strategic sorting reduces Black/Latino representation at UT but also leads to less high school segregation.

All told, Top X% is not a panacea for society’s problems, but it seems pretty good. Of course, the fanciest and most famous schools in America are not public state universities. And this litigation is about Harvard.

The affirmative action U-curve

Most Asian Americans attend college, but for all other ethnic groups (and the country as a whole), most people do not. And most people who do attend college attend non-selective schools. So the affirmative action question the court is currently considering is of limited relevance to the typical person.

But precisely because there are so many students attending non-selective schools, the impact of affirmative action on the distribution of students is a little bit odd.

Peter Arcidiacono and Michael Lovenheim plot the Black share of the student body at any given school against that school’s average SAT score and find a U-shaped curve. The most elite schools in America are admitting Black students who, absent affirmative action, would have attended other selective schools — just somewhat less selective. But then there’s some floor below which this doesn’t happen.

When California banned affirmative action at UC schools, it ended up pushing a bunch of Black and Hispanic students out of the system. But if the Supreme Court makes the Ivy League stop doing it, that will push Black and Hispanic students out of the Ivies and into public state university systems.

For some schools, it will actually become easier to assemble a diverse class and seem like good progressive allies. The big issue is going to be that, as we saw with the Harvard charts up top, the most elite schools end up with even fewer Black and Latino students. In terms of contemporary sensibilities, that’s going to be a problem for those schools since most of their students and faculty have left-wing political commitments.

But it’s only a problem for society if our other institutions insist on only recruiting from a small set of schools. A good solution to that is to broaden the pool.

Less credentialism would help

Joe Biden has committed to nominating a Black woman to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court, which as I understand it likely means Ketanji Brown-Jackson (who went to Harvard), Leondra Kruger (Harvard), or Candace Jackson-Akiwumi (Princeton).

And I think if you ask the Ivy League schools to give a high-minded explanation for why it’s good for society that they get to solve their internal diversity issues on the backs of less-selective schools, this is what they would point to. Because the most elite colleges in America are diverse, it is now possible for elite institutions in the grown-up world to hire a diverse group of graduates of elite colleges. You might imagine that absent Harvard and Princeton, none of these Black Ivy-educated judges would be on the bench at all.

But is that really true?

When Jimmy Carter made Reynaldo Garza the first Mexican American appellate court judge, he picked a guy who was a graduate of Texas Southmost College. And a lot of Carter’s picks were like that. Lyndon Johnson put Thurgood Marshall on the Supreme Court, but Carter was the first president to seriously try to diversify the bench in racial terms, which at the time meant appointing people with non-elite educational credentials.

The norm that judges must possess ultra-elite educational credentials is actually quite new. The Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court had only one Ivy Leaguer, four graduates of public colleges, and one guy who didn’t go to college. And I think they did fine.

In contrast, relying on identity considerations is pretty old. There used to be a “Jewish seat” on the Supreme Court, and for over 20 years it was held by Felix Frankfurter, who went to City College of New York. I think it is a lot easier to give a coherent account of why descriptive representation matters in public office and coalition management than to give a coherent account of why Supreme Court justices need to have high SAT scores.

Absent affirmative action, we may need to confront more squarely the tension between representational demands and credentialism. In a lot of areas, the solution is to let go of credentialism.

Give money to the students in need

A lot of attention is paid to “college costs,” as in the price students pay to attend.

But higher education financing is very convoluted, so what it costs to attend a school can be quite different from what a school spends educating its students. It turns out that the most-selective schools spend the most on instruction (that’s “comprehensive cost”) but also generally charge lower tuition to low-income students. These schools are rich and don’t admit many low-income students, so they can spend lavishly on both general instruction and on financial aid to the small number of talented students from low-income families they do admit.

I think the real message of the Bleemer paper and of the Black, Denning, and Rothstein paper and of the Dale and Krueger paper is that this is perverse.

Sometimes it does make sense to invest the most resources in training the most elite prospects. But at least at the current margin for American higher education, we would get better returns by giving money to help teach the weaker students. Whether through affirmative action (Bleemer) or Top X%, it is beneficial to be a below-average student at a more-competitive college because the more competitive college will devote more instructional resources to you.

It is obviously in the narrow interests of Harvard to keep fighting for a world in which Harvard gets tons of money and then wins social justice points by having a racially diverse class.

But from the standpoint of social justice, by far the preferable option is to redistribute the money away from the institutions that have so much and give it to the ones who serve a more diverse set of people from more modest backgrounds.

I think a major cultural shift that is needed in this country is to normalize and promote the idea that the majority of students should attend (and graduate from) a two-year community college before attending a four-year institution. There is no significant difference in what one can learn in an English 101 class taught at Harvard and one taught at Northern Virginia Community College (Go Nighthawks).

In fact, it will likely be a better learning environment for most students because they’re more likely to be taught by a professor who is focused on teaching the subject and not a researcher who couldn’t be bothered and who shirks most of their duties to a grad student that has almost no teaching experience. (No, I’m not bitter about some of my intro comp-sci classes. Why do you ask?)

Finally, community colleges are almost guaranteed to be more diverse campuses than even the most affirmative-action-practicing elite institution. Not just racially, but also in terms of economics, age, and life experience. There is a genuine benefit for all students to be part of a diverse community that allows them to meet and interact with a broad range of people, and community colleges are far more likely to actually provide this benefit than most four-year institutions.

I'm going to avoid the temptation to pontificate on the injustice of race-based affirmative action and try to focus on Matt's stated thesis: What we should do after (race-based) affirmative action (assuming it gets overturned by the SC) is redistribute resources away from the richest, most exclusive schools. Like many of Matt's culture war-type posts, I feel like he buries his unique stance on these topics by dedicating too much ink to relitigating the heavily debated aspects. I kind of had to force myself to re-read for the meat.

Matt proposes:

-Putting less emphasis on elite school credentials when selecting candidates for elite positions like the SC

-Consider using the Top X% approach more broadly, which would have the effect of racial diversification while staying truer to progressive values

-Spend more resources on low-income students (specific method not shared here)

I agree with all of that. I think Matt kind of misses the heart of the issue here, which is, what problem are we trying to solve with any of this? Increase ease of upward SES mobility? Reduce the structural advantages of being born into a privileged, connected class? Maximize return on investment (of time and money) for every college-aged American? Make America fairer? More competitive? So much of this discussion is based on people's unstated values and goals. It's pretty easy to poke holes in the hypocritical values vs. actions approach of elite private universities, and it's fair to say that it's within the scope of the federal government to outlaw race-based discrimination in college admissions. But answering the question of "what next" requires some clearly stated public domain goals, and I don't think we have those as a nation when it comes to this discussion. I think Matt's unstated goal/value, which I share, is that we should make circumstances of birth less of a dominant factor when it comes to access to opportunity (which I personally think should be the goal of any morally consistent social justice movement) but this isn't necessarily the goal of American conservatives or progressives. Conservatives might prioritize American competitiveness, which might say it's more important to be brutally cutthroat about elite institution admissions, and progressives might prioritize group-based equality of outcomes. These unstated value judgements will influence one's ideas of what steps would be "fair" or "right."