What the 15-minute city misses

Great cities are vast interlinked agglomerations, not just patchworks of neighborhoods

I live around the corner from my son’s elementary school. We’re five minutes from a Trader Joe’s and 10 minutes in the other direction from a Whole Foods. Within that radius are six coffee shops, a kid-friendly diner, several pizza spots, a good Sichuan restaurant, a good Vietnamese restaurant, a good French bistro, a less-good French bistro, two Spanish restaurants I like, a Chipotle, a decent bagel shop, and a fast-casual salad place.

We’ve also got a CVS and a hardware store.

Extend the radius five more minutes and you’ll find my favorite dive bar, a Walgreens, our family dentist, and a bunch more restaurants. So I guess I’m living in a “15-minute city,” to use the new-ish jargon for a neighborhood where life’s daily errands can be met without a car. This concept has also become the subject of insane conspiracy theories about some kind of plot to prohibit you from going further than 15 minutes from your house. That’s stupid, and it’s not what proponents are talking about.

But even though I personally enjoy my walker’s paradise neighborhood and obviously support things like missing middle housing, dropping parking requirements, and pedestrian-friendly street design, I’ve never liked the frame of the “15-minute city” as a policy goal.

This has been hovering around the periphery of my consciousness for years now, and I’ve generally thought of it as a harmless but slightly misguided framing concept. But I worry now about polarization dynamics. If conservatives respond to the 15MC with conspiracy theories that then get debunked in mainstream media sources, it could lead people who’ve never heard of any of this prior to this year to decide that they need to become super invested in the concept.

And as a concept, the 15MC leaves out a lot. The 15-minute threshold is totally arbitrary, for starters. More fundamentally, though, it misconstrues what’s valuable about urban agglomerations — it’s wrong to think of great cities as just quilts of neighborhoods; the urban whole matters.

I don’t want to join a pile-on against people who are promoting good traffic-calming measures and mixed-use development. I agree with a lot of their policy goals! But I also don’t want to find ourselves in a situation where the 15-minute city slogan becomes the marquee framing for good urban planning.

Meet a true 15-minute city

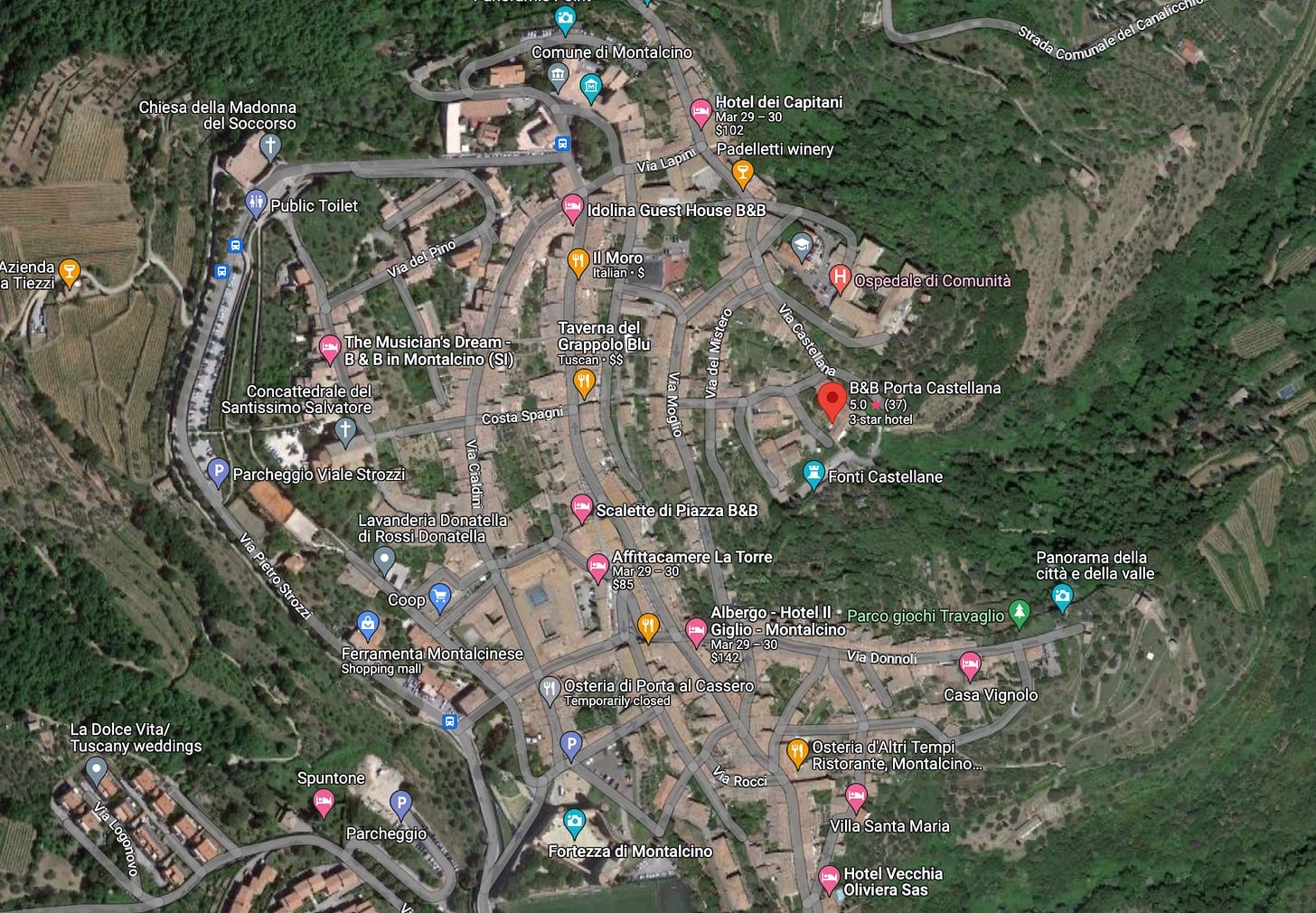

Last summer, my family and some friends rented a house just outside the walls of Montalcino, a tiny medieval city in Siena that has a very small modern section just south of the walls but is otherwise surrounded by vineyards and countryside. Italy has an extensive railroad network, but there’s no train station in Montalcino. If you want to leave, you need a car — but parking is obviously very scarce inside the medieval city, and driving on those tiny streets is pretty restricted. So even though lots of people drive to and from the parking lots near the city, there’s very little driving around town.

As you can sort of see on the map, basically everything you need is there in town — an easy walk from everything else. The schools, a small hospital, a supermarket, several banks, two pharmacies, various restaurants and hotels, and basic personal and professional services are all available. It really is a pretty literal 15-minute city. The walk from the fortress at the south end of town to Porta Burelli in the north takes 12 minutes according to Google. The walk from the panorama on the east side of the city to the Chiesa della Madonna del Soccorso on the west takes 13 minutes.

It makes for a very neat place to visit. I really enjoyed our time there, and it’s no surprise that Montalcino has a lot of small hotels and B&Bs. Judging by the license plates I saw in the parking lots, it also seems to attract a lot of visitors from Austria, Germany, and Switzerland who are road-tripping through Italy.

But spending time in a place like this, a few things become evident pretty quickly. One is that the emergence of this sort of situation requires odd historical circumstances. There is an incredible amount of charm to an old medieval walled city, which is why people love to visit Tuscany. But it’s not a particularly practical way to build things in the 21st century. If you were building something brand new, people would want larger dwellings and better insulation. Because modern-day wages are higher, it would be impractically expensive to do some of the detail work associated with old architecture — things would look more plain and modern. People would also want places to park their cars, and they’d want streets that were wide enough to drive cars on. Even if you didn’t require parking or ban multi-family housing, that’s the reality. Montalcino wasn’t built to be convenient to drive around because cars didn’t exist when it was built.

Beyond that, though, even though you can meet all your daily needs in Montalcino, that doesn’t change the fact that this “15-minute city” is actually a small town.

Small towns are great, many people like to live in small towns, and I support the continued existence of small towns. But cities play an important social and economic function that small towns just don’t. There are lots of things you can’t do in Montalcino. You can’t attend university, for example, because there doesn’t happen to be one there. And while some small towns contain universities, for every small town to have a university would be way too many universities. You also can’t be an executive at a major multinational corporation — even though it’s a nice town, it would be impractical to locate a major corporation in a place that’s so small and out of the way. You also can’t really be a research scientist. There are lawyers in Montalcino, but they’re small-town lawyers. If you want to see certain kinds of medical specialists, you’d have to go to a big city. There are no big-time pro sports teams in Montalcino. Bands don’t tour there. American small towns are very different than historic Tuscan ones, but these are inherent properties of small towns across space and time. There’s just less stuff happening than in big cities.

A city isn’t just a bunch of neighborhoods

A very funny thing about American cities is that people often describe D.C. as “a city of neighborhoods,” but they also say this about Philadelphia, Chicago, New York, and everywhere else.

People say this about every city because on some level, it’s true of every city. These places are very large, people spend most of their daily life in a particular neighborhood, and the vibes differ enormously from neighborhood to neighborhood. At the same time, when I hear the mayor of Paris talking about 15-minute cities, I feel like she’s missing something incredibly important about how actual large cities function and why they exist.

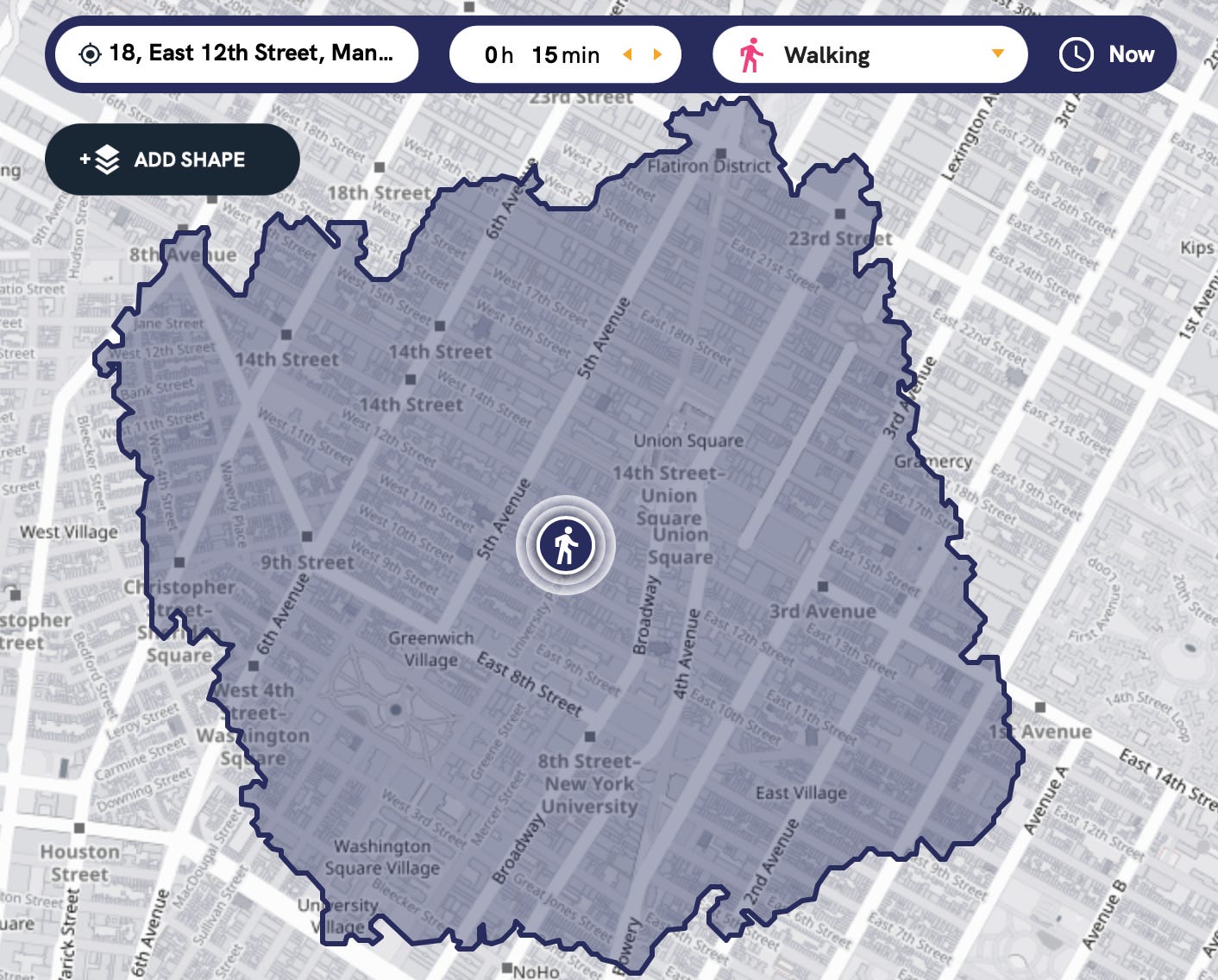

Here’s the 15-minute walkshed from the apartment I lived in as a kid in New York. Like Montalcino, this arbitrary slice of Manhattan encompasses everything one needs for daily life.

But to think of New York as just a bunch of these 15-minute walksheds quilted together would be missing the point of New York City.

Most of all, even though you in some sense “could” live your daily life within these boundaries, I don’t think actual people do that. I went to high school way up on East 89th Street. But my friends and I also hung out a lot at the apartment of our buddy who lived on Houston and Sullivan, just a stone’s throw outside the 15-minute radius. We liked to go down to Chinatown to eat and hang out. I’d sometimes go see movies at the Angelika, which Google tells me is a 16-minute walk from my apartment.

I know it sounds a little fussy and literalistic to be talking about 16 vs. 15 minutes, but my point is that superior access to things matters at all points along the curve. Google says it takes 19 minutes to get from my apartment to my high school on the subway. If there were no express trains on the Lexington Avenue line, the trip would be longer and my life would have been worse. If the Angelika were 25 minutes away rather than 16 minutes away, my life would have been worse.

Improving access matters across all points on the time curve.

When you’re thinking about transportation improvements, there’s no magic at the 15-minute barrier. Building quad-tracked subway trunks so you can run express trains isn’t something I would recommend that most cities do, but the fact that Manhattan has them is extremely relevant to its functioning, even though it doesn’t put anything within 15 minutes of anything else.

Beyond that, people go to things for reasons other than proximity. The Angelika was not the closest movie theater to my house. I went to those theaters, too, but I went to the Angelika because they showed movies those other theaters didn’t. And while Angelika played independent and arthouse films, Cinema Village specialized in Asian movies — that’s where I saw John Woo’s heroic bloodshed films, Jackie Chan’s old Hong Kong work, and Beat Takeshi’s Violent Cop and Hana-bi.

That’s not a business that functions based on drawing people in from a 15-minute walkshed. It functions because it’s situated in a city that’s large enough to support weird niche businesses. Chess Forum down on Thompson Street and The Strand and Forbidden Planet on Broadway are other cool retailers that were within my 15-minute walkshed but whose existence very clearly depended on drawing customers from well outside the neighborhood. And a big part of what New Yorkers like about living in New York is the ability to go to marquee cultural amenities that may not be 15 minutes from where they live but that don’t exist at all in other cities. These are not incidental facts about major cities. The New York City metro area has 20 million people in it, which means it contains things that would not exist in 20 separate metro areas of one million each. And a modest-sized metro area of one million people is not 100 different small towns smushed together. Agglomeration has emergent properties that generate forms of specialization and productivity gains that are not reducible to “we have a lot of different neighborhoods here.” Cities have deep markets for both labor and locally-facing services, and the better you can make your housing and transportation system, the deeper those markets can become.

A better case for good things

D.C. has lots of neighborhoods where the market price of housing dramatically exceeds the construction costs of building new units. That’s typically because of regulatory barriers to adding new units. Those barriers include minimum parking requirements, minimum building setback requirements, maximum building height requirements, and maximum floor area ratio requirements. If you eliminated (ideally) or relaxed (realistically) these rules, those neighborhoods would become denser. Relaxing the rules would be a good idea for the city because it would grow the economy, create jobs, and help stabilize a tax base that is currently under tremendous pressure from remote work. With a growing tax base and economy, we could maintain our existing level of city services while cutting tax rates. Or we could improve services without raising taxes.

If neighborhoods became denser, the number of cars per person would fall, which would create more robust small-area markets for retailers.

Another thing about cars is that they take up a large amount of space per person, so in a city that’s crowded, you can improve the throughput of people by constructing subways and also by allocating street space to denser forms of transportation — walking, biking, bus lanes.

I don’t know how different this really ends up being from the FMC policy prescriptions. But it is a distinctly different frame, one that emphasizes the benefits of growth and transportation policy as a solution to practical problems. You want to maximize people’s mobility, and what that means will depend on the situation. You don’t want to arbitrarily cap population growth for the sake of cars in a way that cripples the economy. But you also don’t want to gaslight people into thinking that cars are never a useful mode of transportation or to falsely imply that there is some magical fifteen-minute time-and-distance tipping point. Small towns have their charms and lots of people like them. But very large cities have their own unique virtues that are not reducible to questions of local pedestrian access.

It would be silly to pretend that better framing would eliminate right-wing conspiracy theories. But at the same time, we should resist the impulse to polarize ourselves around this particular idea. The FMC concept is a good theme for a TED Talk, but it never should have become a dominant element of urbanist discourse. We should let people build more where there’s a demand for building, we should use street space in a way that maximizes the travel access of humans rather than of cars, and we should build transit projects when they are likely to attract riders. This will lead to more people living within a fifteen-minute walking distance of various things, but that’s not the goal of policy any more than the goal is to have people be within 45-minutes of a movie theater that plays Asian films. Urban agglomeration works on multiple scales, and we should try to build functional communities.

"The X concept is a good theme for a TED Talk, but it never should have become a dominant element of Y discourse," for all X and Y.

I think slogans for urban planning concepts draw attention. Some attention is good - people may be excited about the concept and get interested in the field, or just understand the value of mixed use and walkable places in a way they never did before and might not if things just stayed more technically precise. Also, it draws nutcases to attack it.

As a general matter, should people avoid ever making urbanist concepts exciting because of the nutcases? Because I think the same would generally happen as much with any concept. And worse with some, like congestion pricing.

I think the substantive critiques of the 15 minute city are technically fair but mostly irrelevant. Of course the concept isn’t perfectly trying to cover everything and I don’t see people pining for Montalcino; it’s a way to better conceptualize and communicate the value of walkable urbanism in cities.