What everyone is getting wrong about crime in DC

And how to get it right

Charles Fain Lehman is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a Contributing Editor of City Journal.

If you’ve followed the news about Washington, DC, in the past several years, you may have heard the city has a crime problem. The Washington Post has covered it; so for that matter, has Slow Boring. In an April Post poll, more than 60% of residents described the city’s problem as “extremely” or “very” serious.

The District’s crime wave has attracted attention not just because of its location, but because it has been longer and bigger than that experienced by other major cities, many of which saw violence begin dropping in 2022, and which are back to historic lows in homicide. DC is not, in other words, enjoying the gains that other cities are reaping. There have been positive signs: Violent crime is down over last year, as a wave of carjackings has somewhat abated, and homicides are running below recent highs. But gains there seem to be coming at the expense of quality-of-life issues, like a collapse in traffic enforcement or a large uptick in 311 requests for sanitation enforcement.

But what, actually, can the city — and the federal government constitutionally responsible for it — do about their crime issue? As I argue in a recent Manhattan Institute report, almost everyone has been thinking about the problem wrong. Analyses have tended to focus on a broad “crime” problem, not zooming in on specific problems; solutions have fixated on the severity of the criminal law, whether seeing it as too harsh or too lenient.

After taking a deep dive into DC’s crime data, I have a different view. The city’s core problem is its capacity to address its issues. Across every measure, the District’s systems for controlling crime are doing less than they used to. And until policymakers — federal and District — take that problem seriously, they’ll be fighting uphill to get crime under control.

DC doesn’t have a crime problem

It has crime problems.

Too often, debates about “crime” treat it like a single, continuous variable, either up or down, better or worse. The implication is that all crimes have the same fundamental cause, moving in tandem based on the variation in a preferred variable. In reality, crime is highly concentrated among small groups of people and in small areas. Where it rears its head, it’s often the product of specific failures of the systems meant to control it. There is no one crime problem. Instead, there are many crime problems.

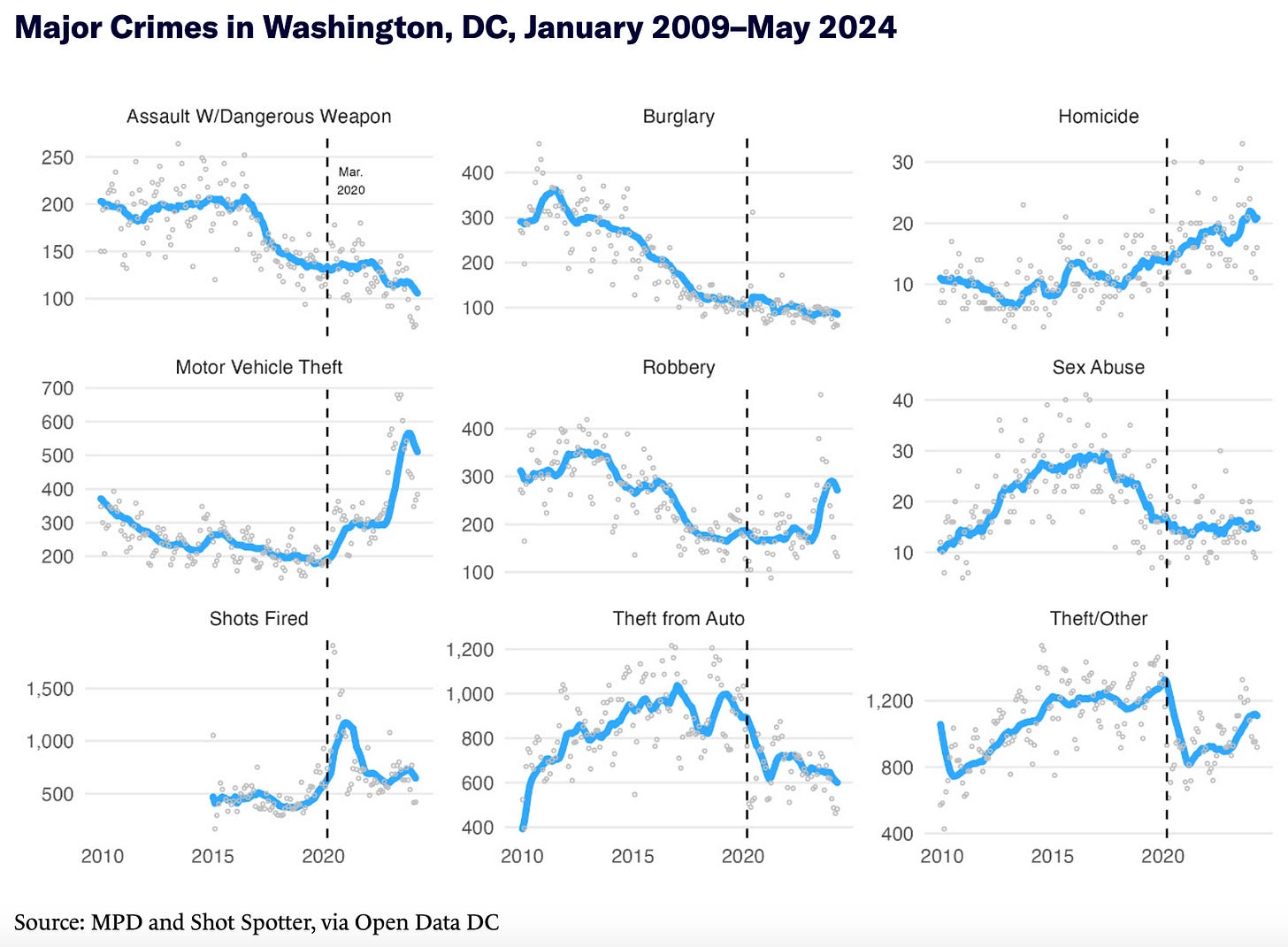

As much is true in the District. Data from MPD show that since 2020, several kinds of crime have remained flat, or even fallen. Offenses like burglary, theft, and sex abuse have all fallen, possibly as the COVID pandemic reduced opportunities for offending. The city has experienced a steady increase in homicides, as well as an increase in motor vehicle theft (and robbery, a category which usually includes car theft that involves force or threat of force).

What’s driving these problems? Murder in DC is well understood. A city-commissioned report from the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform found that between 200 and 500 people are responsible for 60 to 70% of all gun violence in the District. This small group are “primarily male, Black, and between the ages of 18–34,” with an average of 11 prior arrests; at least half were identifiably in a gang. Car theft in the District, meanwhile, appears to be driven by delinquent teens. My analysis of MPD data finds that 79% of those arrested for carjacking offenses between 2020 and 2024 were 19 or younger.

There’s another important component of DC’s crime perception problem: increasing public disorder. City 311 data show a steady increase in requests for sanitation enforcement since early 2021, with over 1,200 calls per month as of 2024. Before a crackdown, fare evasion accounted for 10 to 13% of WMATA ridership. Regional data show that unsheltered homelessness has risen sharply since 2020, even as overall homelessness has fallen.

Such problems don’t necessarily rise to the level of “major crime,” and the solution isn’t serious prison time. But they still affect residents’ quality of life and — relevantly — their perception of crime. If DC has gotten more disorderly in the past four years, that may explain part of why citizens feel like “crime” is out of control.

The problem isn’t culture, it’s capacity

When crime rises or falls, we tend to make the same arguments about why. So it is with DC. Those on the left say that the problem is inequality, racism, and other “root causes.” Those on the right focus on whether the law is punitive enough. Both look at big social and cultural factors to try to explain sometimes-minor year-to-year variations.

I think we should look elsewhere.

As I’ve written previously for Slow Boring, we often undervalue the importance of the criminal justice system’s “capacity,” or the volume of resources that the system can dedicate to addressing the problem of crime.In the long run, no matter how kind or cruel the criminal justice system’s normative framework, its efficacy is ultimately determined by its capacity to actually enforce the law. This “capacity view,” I’ve argued, has the potential to unify progressives and conservatives, because it emphasizes the importance of both law and order and competent, well-funded government services.

And when we look at the data, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that DC’s problem is a lack of capacity. Whether by choice or external constraint, DC’s system is simply doing much less than it used to.

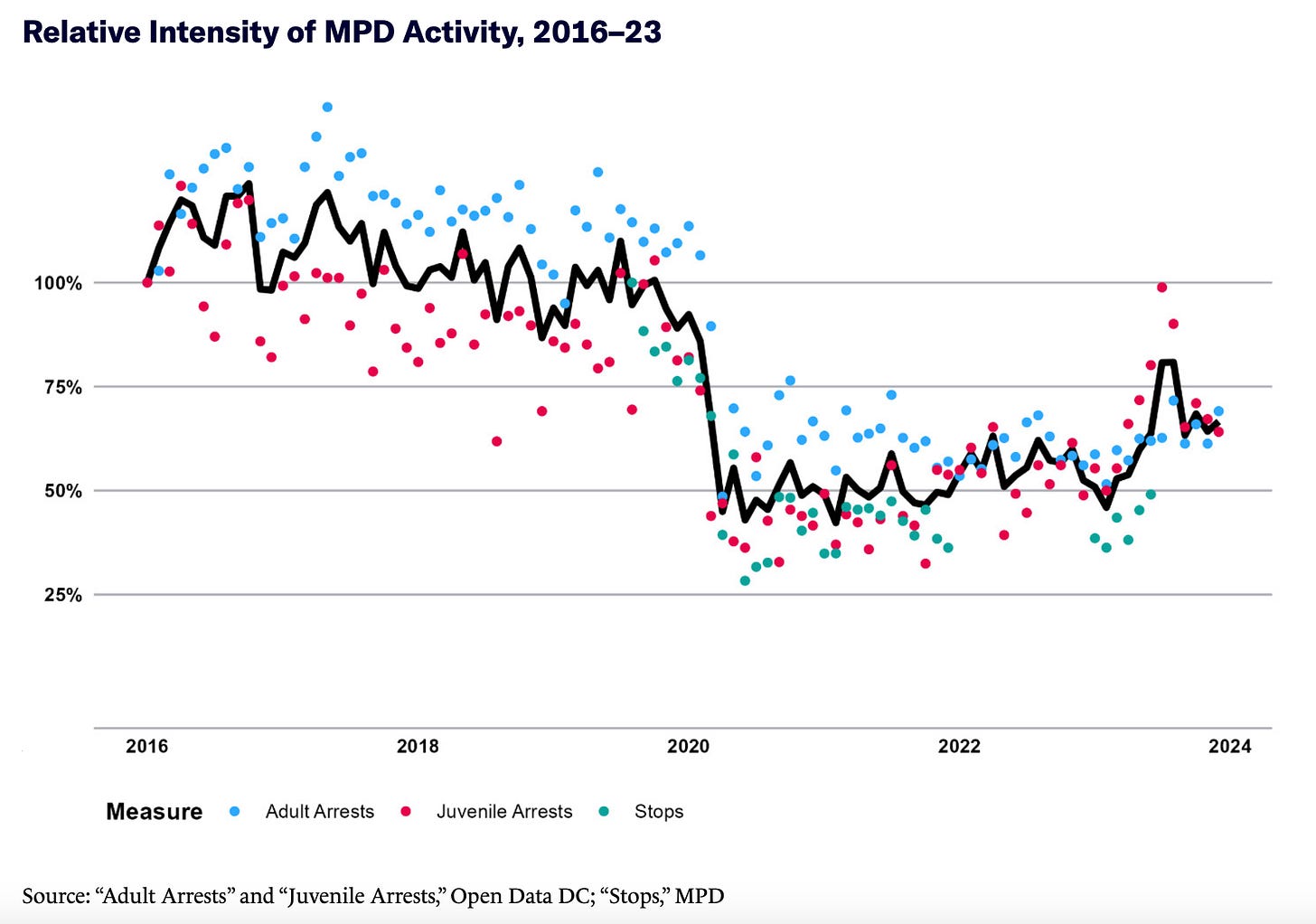

The most clear-cut case is MPD. As the chart above shows, levels of MPD activity — as measured by an unweighted average of stops, adult arrests, and juvenile arrests — fell to about half its pre-pandemic level in 2020, and has only somewhat recovered as of the most recent data. MPD has all but stopped enforcing many minor offenses. Counts of arrest for traffic violations, disorderly conduct, and DWI fell 78%, 69%, and 51% between 2019 and 2023, respectively.

Some large part of this decline is attributable to a drop-off in staffing, which has fallen by nearly 500 officers to a half-century low. Actual district-level staffing, which excludes administrators and bureaucrats, is down 17%. But the remaining officers are also doing less, with arrests-per-officer also down.

MPD isn’t the only part of the system not doing its job, though. As many have noted, US Attorney Matthew Graves has slashed the share of cases referred to his office that he actually prosecutes, prosecuting less than half of referred felonies in 2022. Where he does prosecute, charges are often plead down. Of unlawful gun possession charges that his office actually prosecuted in 2023, for example, half were pled down to a misdemeanor — a questionable choice for a city so wracked by gun violence.

MPD and the US Attorney get headlines, but other parts of the system are working less well, too. In May, the chief judges of DC’s criminal court system called attention to the fact that nearly 20% of the seats on the city’s trial bench were vacant. Since then, the Senate has confirmed some judges. But as of June, the trial court was still missing 10 judges, and the appeals court two of its full complement of nine.

Then there are the parts of government that, while not formally part of the criminal justice system, still play an important role in “social control.” Minors are driving the city’s carjacking problem and, not coincidentally, the city has a massive issue with truancy. As of the most recent data, 35% of students were absent without excuse 10 or more times. That represents a decline from the 2021-22 school year, but a large increase over pre-2020 normal. The city’s response to public camping, too, has been halting. While camp clearances rose in early 2023, they seem to have fallen towards the end of the year, even as unsheltered homelessness continued to rise.

Both the Feds and DC need to do more

There’s a certain virtue, from a politician’s perspective, to taking easy explanations for changes in crime. Blame it on soft laws, and you can tighten up penalties without increasing official spending figures; blame it on “root causes” and you can kick the can down the road until someone figures out how to solve poverty and homelessness. The capacity view, by contrast, demands real investment in making the system do more. That costs money and political effort. But it’s also worth doing, especially when an underfunded and inactive system yields such unpleasant results.

In the case of DC, doing more is the responsibility of both of its governments. In my recent report, I outline a number of proposals for both, which will hopefully make DC safer both in the short and long term.

Start with MPD, the workhorse of DC public safety. The city needs more hiring, and Congress can give them funds, earmarking dollars for DC through Community Oriented Policing Services office’s hiring grants. But the city also needs to focus on retention, because keeping officers on the force longer increases manpower without added training costs. An evaluation conducted by the Police Executive Research Forum found that MPD officers often leave the force because they feel they lack opportunity for advancement. Giving line officers more experience across roles, increasing transparency in hiring, and trying to expand education opportunities at the DMV’s world-class criminal justice programs (at George Mason University and the University of Maryland) could help make a career in policing more attractive.

The US Attorney’s inexplicable reduction in prosecution has a short-term fix: fire the US Attorney. President Biden’s apparent unwillingness to get rid of appointees might be a constraint here. Perhaps Vice President Harris, looking to polish her tough-on-crime bona fides and distinguish herself from the administration, could push for him to make an exception. But there’s also a more structural fix. The District has an elected prosecutor, the DC Attorney General, who is primarily responsible for civil and misdemeanor issues. Congress could modify his ambit, letting the DC AG prosecute any case that the US Attorney declines to prosecute. Doing so would just give the District what most cities already have — both a state and a federal prosecutor responsible for their safety.

Fixing the District’s courts has a similar short-run fix: appoint more judges. But DC criminal judges are never going to be the top priority in a desperately gridlocked Senate. And, unlike other federal judges, there is no Constitutional reason that the Senate must vote to confirm DC’s judges. Consequently, Congress could just alter the appointment process, giving the Senate a time-limited veto over recommendations from the DC Judicial Nominating Commission. If the Senate doesn’t vote down a candidate in three months, the president can confirm her to the bench — and the Senate could then revisit the appointment after a statutorily determined term had elapsed.

There are other fixes the District’s leaders could consider. For example, they could do more to advertise the power of citizens to fight crime. DC law lets citizen groups sue to shut down drug- or gun-related public nuisances, and the city’s Advisory Neighborhood Commissions have the power to revoke the licenses of liquor stores and bars that attract crime. The DC Attorney General could use truancy prosecution as a way to detain and divert kids who commit other crimes, hopefully minimizing both crime and punishment. And the city can clear camps without apology — they do harm not just to everyday citizens, but to the people who choose to live in them.

These proposals are just some among those I’ve identified. The through-line, though, should be clear: If District residents want less crime, they need to focus on making their criminal justice system work better.

I feel like this article misses the core question, which is why exactly capacity has fallen so much across so many systems simultaneously. It would make sense to say "ah, police are quietly protesting after the BLM protests, that is why policing capacity has fallen", but how does that explain missed trash pickups or school truancy? Just saying "we should allocate more resources to fix capacity problems" feels perilous when we don't seem to have a solid understanding of why it has fallen so much, so quickly, in so many (at least superficially) unrelated domains.

I don't have a good answer, but spit balling some theories that come to mind:

1. What if all these systems are way more connected than they seem at first blush? A failure in one cascades to the others, reverbating back and forth in a vicious cycle. Fewer cops means that no one locates truant students which means kids have more time to fare hop on WMATA and so on. I'm not sure how this trickles all the way down to trash collection though.

2. Post-COVID malaise? Everyone just kinda realized how much they could coast during COVID, and that social fellow feeling has not fully recovered. The sort of minimum standard of trying to not feel ashamed of yourself has been hollowed out during COVID, and this shows up all across the board: why should I dot my I's/go to school/do that extra trash pickup/write this fare hopping ticket and so on.

3. Maybe the city budget isn't adjusted for inflation somehow? So all services are 25%+ more expensive to provide, resulting in a commensurate drop in capacity. Relatedly, I'm not sure where DC's tax revenue comes from, but maybe WFH has hit its tax revenues harder than other cities? Though intuitively I'd imagine that government is LESS prone to WFH than most other white collar work...

4. Maybe corruption increased during COVID? I could be mistaken, but I think DC has had issues with this in the past. A large new corruption tax could degrade the capacity of all systems simultaneously.

As a DC resident who experienced the post Floyd/Covid crime wave first hand, I have some thoughts here -

1. MPD's less aggressive enforcement was mainly driven by top down pressure from the District Council. They wanted less enforcement, less pretextual stops, and made it clear they'd legislate that way and were overtly hostile to any proactive policing from MPD. When crime spiked, councilmembers conveniently forgot this part and started asking why "MPD isn't doing their jobs?".

2. I can't find the original source, but I remember seeing something about a policy change at MPD on how they respond to calls. In essence it was that in order to avoid situations where one officer is trying to subjugate a suspect and might have to use increasing force, their policy is to now have multiple officers for every police interaction to cut down on those scenarios. If you drive around town, you'll notice any time MPD responds to something, no matter how minor, there's at least 3-4 squad cars there. This would obviously cut down on arrests if you have 5 officers doing something that 1-2 used to be able to do.

3. As noted, the US Attorney basically stopped enforcement against any misdemeanors. Retail theft exploded when it became apparent that there were no consequences. Drug dealing came back to areas I hadn't seen it in for at least a decade. Judges release known violent defendants back into the community where they continue to commit crimes while awaiting trial. There are some very obvious and easy solutions that could curb crime dramatically here.

4. The city's GPS monitoring of people on release (DC eliminated bail many years ago) is basically fake. It's not being monitored 24/7 and is not an impediment to committing additional crimes.

5. When the city legalized marijuana, it coincided with a complete stop of prosecution for people using it in public (which is still illegal!). It is extremely common to see people driving vehicles while smoking weed, which is bad.

6. Trash pickup got really bad during covid, which was weird because DPW has always been one of the best run city services. It seems to be back to mostly normal now, but its drop off and addition to the general sense of malaise in the city was curious.

7. Progressive activists made a huge deal out of the homeless sweep at McPherson Square and how devastating it would be to the local people experiencing unhousedness community. However now that it's done I haven't seen any follow up showing how devastating it truly was, and the park is now usable for all city residents and workers again, which is nice. Additionally, there was very little backlash from anyone outside of the usual DSA/Anarchist/Lefty groups. I think it showed the city that the activists claimed to speak for many more people than they actually do.

8. Things seem to be slowly getting back on the right track. Fare enforcement on Metro has been popular, the previously mentioned McPherson Square cleanup, and I've even seen an uptick in traffic enforcement. I'm cautiously optimistic that the 2020 collective fever is slowly breaking, and that we can get back to being a world class city.