We're getting an Omicron-optimized booster many months too late

Covid isn't done and we need more urgency in our vaccine approval process

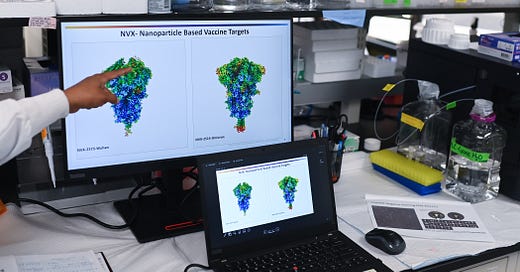

The FDA is calling for booster shots to be reformulated this fall to specifically target the Omicron variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The mRNA technology behind the shots is supposed to make it fairly easy to tweak vaccines to target new variants. And the virus has evolved so rapidly that an update seems obviously warranted — classic Omicron (BA.1 on the chart below) is already gone from the world, and even BA.2 is rapidly fading in favor of BA.5.

All indications are that (a) vaccines work against BA.5 in the sense that you are better off vaccinated than unvaccinated, and (b) an Omicron-optimized vaccine will be better against BA.5 than a classic vaccine.

So in a narrow sense, this is clearly the right policy call: we ought to update the vaccines, and we ought to offer a new round of boosters to people with the updated vaccines.

But in a broader sense, we’ve gone from the impressive technical achievement of rolling out the original vaccines in record time to a sorry situation in which the FDA is authorizing Omicron-optimized boosters only after Omicron has vanished from the earth. We’re not even really going to get these shots in people’s arms in time to protect them from BA.2 — we’re hoping to catch BA.5 with a vaccine that is two variants old. And what’s particularly upsetting is the clinical trials for the Omicron-optimized vaccine started on January 25. The science itself was done before the trials began.

As Eric Topol writes, “it took more than 7 months for the Omicron BA.1 booster to be tested, a delay that is exceedingly long and unacceptable relative to the timing of validation and production of the original vaccines in 10 months during 2020.”

Slowly updating vaccines to chase variants that are already in the rearview mirror is not an acceptable global Covid strategy. We need to speed up the pace of clinical trials and invest serious financial resources in developing next-generation vaccines.

Most people seem to have tuned-out vaccination

I exist in the sociopolitical bubble where the people I know who are eligible for a second booster have mostly gotten one, where kids eligible for boosters have gotten boosters, and where parents of very young children were excited about the authorization of shots for young kids and rushed out to get their toddlers vaccinated.

Most of the people who do public health journalism, most of the relevant bureaucrats, most of the people who run the Biden White House, and most of the academics commenting on public health issues in the media are here with me in this bubble. But it’s really worth underscoring that the majority of the public is not. Most adults got vaccinated soon after that became possible, and a large minority of older children got vaccinated.

But when making policy, it’s important to acknowledge that a majority of the public is not in this bubble. According to the CDC, very few non-seniors are boosted at all. We also know from previous reporting that the CDC is almost certainly overcounting boosters and undercounting first shots. So the reality is that to a very large extent, Americans got their first shots and then just moved on, tuning out subsequent vaccination efforts.

It seems to me that public health officials have been spending way too much time worrying about whether new vaccines will undermine confidence in existing ones and splitting hairs about who is vulnerable enough to be eligible for a second booster. The reality is that we should be allowing anyone who wants additional boosters to get them, recognizing that the practical demand is likely to be low. But we also need to recognize that improving the actual biomedical technology is critical to improving uptake. Covid has gotten sufficiently tangled up in nasty politics and ill-will that a significant share of the population is now showily defiant about virus risks.

If we could tell people something like “every fall you’re going to get an up-to-date shot optimized for the latest variant,” then we could probably get decent uptake like we do with the flu shot. But telling people that every fall you’re going to get a booster optimized for the variant two variants ago is absurd — we need to work faster than that.

We need faster approvals

Back in February of 2021, the FDA suggested that in the future, variant-optimized vaccine updates would be fast-tracked for approval.

They suggested at the time that companies “would need to submit new data that shows the modified vaccine produces a similar immune response and is safe, similar to the process for annual flu vaccines,” and this could be done “without the need for lengthy clinical trials.”

That would have been a good idea! But instead they seem to have opted for months of intensive clinical trials. The problem there, which should be obvious, is that while the clinical trials enhance our confidence that the new booster is in fact more effective against Omicron, they also radically decrease the real-world efficacy of the Omicron-optimized booster by ensuring that it gets into people’s arms far too late. As the original coverage stated, the FDA understands this tradeoff perfectly well in the case of the flu vaccine. Incidentally, it is genuinely true that because flu vaccines are sort of rushed out the door, their efficacy varies a great deal from year to year. In theory it would be better to test more carefully. But time is of the essence so the best thing to do, all things considered, is approve vaccines quickly and let people get their annual shots.

Doing the same for Covid seems like a no-brainer, but for some reason they didn’t do it.

The good news, however, is that they very recently announced that future optimized boosters will be able to skip the clinical trials.

And let’s note again that if more testing is really truly needed, we ought to organize human challenge trials in which volunteers agree to be deliberately exposed to the virus in order to collect data rapidly. Given the endemic nature of the virus and the collapse of public support for non-pharmaceutical interventions, there is at this point no good reason to avoid challenge trials. You’re not really sparing the volunteers any risks, you’re simply denying people the opportunity to do something heroic and useful for their community.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.