Francis Fukuyama’s “The End of History and the Last Man” and Samuel Huntington’s “The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order” annoyed seemingly everyone when they came out in the early ‘90s. And yet, something about their core arguments was compelling enough that people still reference them both decades later.

I’ve been thinking about these books in the context of the war in Ukraine and the varied responses from countries around the world. The scale of the mobilization against Russia certainly has a “history is back” flavor. Fukuyama fans maintained throughout the Global War on Terror that his book never argued that historical events would stop occurring, but it did argue that a certain flavor of big picture ideological contestation was a thing of the past. And while the volume of sanctioning against Russia is certainly a big deal, it is meaningfully contested. Russia has a powerful ally in China, a durable relationship with India, and many countries around the world who just don’t think a showdown over Ukraine is worth the cost.

But many wealthy states do see Russian aggression against Ukraine as worth upending the global economy, and if you had to characterize these countries, I think the idea of “the West” — complete with the seemingly bizarre gerrymander that assigns Portugal to the same cultural group as Australia rather than Brazil — is useful. So score one for the Clash of Civilizations? Perhaps not.

The current resurgence of great power politics throws into relief the extent to which the civilizations thesis doesn’t hold up in detail. In particular, if you want to understand what’s going on in Ukraine, Fukuyama’s Neo-Hegelian view sheds much more light on the matter than framing the conflict as a war between Catholicism and Orthodoxy.

Events after history’s end

Every time something dramatic happens in the world, someone feeling clever tweets “remember the end of history?” But the actual thesis of the book was that communism was the Final Boss of global ideology and that from there on out, the struggle for democracy would be just a fight against not-democracy — people who want to rig elections or crack down on opposition parties for squalid self-interested reasons — rather than against conflicting ideologies.

I think of Mexico as a paradigmatic example of a country at the frontier of struggle after the end of history.

Mexico has a lot of problems specifically related to governance. The rule of law is weak. The functioning of democratic institutions is uncertain. Crime and political corruption are endemic. But nobody is “against” competitive elections, free press, effective state monopoly on violence, and the impartial application of the law. There are big questions about how to actually get those outcomes and about whether AMLO is making things better or worse, questions about whether American policy is as helpful as it should be. And most of all, it’s just quite difficult to pull out of a bad equilibrium.

But there’s no ideology of “Cartelism” whose proponents argue it’s good on principle to have international drug trafficking gangs that operate with impunity. No young idealists in foreign countries are arguing for the export of Mexico’s governance model to their homelands.

The very boring fact is that creating effective governing institutions is hard. And Fukuyama went on to write two very good, albeit less famous, macro history books on the subject of creating effective institutions (“The Origins of Political Order” and “Political Order and Political Decay”), both of which take as a starting point that the central issue of our time is not big government versus small government (Denmark vs. Australia) but good government vs. bad government (Denmark and Australia vs. Mexico). Where the End of History thesis takes a blow isn’t the continued occurrence of events, but the high ideological stakes of the Global War on Terror.

Islam’s bloody borders

The tumult that al-Qaeda and related groups unleashed on the world is fundamentally hard to fit into the End of History framework.

By contrast, it fits pretty nicely into Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” framework, which posited that the future of world politics wouldn’t be ideological conflict, but the civilizational conflict between broad groups defined largely along religious lines. Islamists did explicitly conceptualize politics as having this kind of religious rather than national or ideological basis. And Huntington observed in the 1990s something he called “Islam’s bloody borders,” a tendency toward wars and violence wherever Muslim and non-Muslim communities found themselves in close contact. That applied most prominently at the time to Bosnia and the conflict between Muslims and Serbs in Kosovo, but also to conflicts in the North Caucasus and Kashmir. Then 9/11 created a dynamic where low-level conflicts involving a Muslim group and a non-Muslim group in places from the Philippines to Nigeria were characterized as proxy conflicts, with the United States typically aiding local governments against Islamist insurgents.

I think it’s incredibly interesting the extent to which this has all faded without any real resolution. The United States did not “win” the war on terror in any real sense, but it kind of petered out. Some GWOT-linked conflicts continue while others have faded. And the whole “bloody borders” idea looks to have been driven largely by demographics — a lot of Muslim countries were very youth-heavy in the 2000s, which is often associated with violence and disorder. The main lines of conflict in the current Middle East have Israel teaming up with UAE and Saudi Arabia to fight proxy battles with Iran, while Turkey and Russia fight some partly-related and partly-distinct proxy battles. Nobody is strictly sticking with a principle of religious or civilizational solidarity here, and crucially, no actual governments have really thrown in with the idea of a pan-Islamic move against “the West.”

If you squint at the first 10 to 20 years of the 21st century, you can certainly see the contours of a Clash of Civilizations. But it doesn’t particularly look like the defining feature of international politics.

The return of “the west”

This is Huntington’s map of the world divided into his civilizations.

It does resemble the map of countries currently sanctioning Russia, with “the west” plus Japan imposing sanctions while everyone else refrains.

That’s of course not to say that every non-sanctioning country is pro-Russian, just that this conflict has a definite vibe of Russia vs. “the West” rather than Russia vs. the world. Probably the most Huntingtonian aspect of the global response is that the sanctions bandwagon includes countries like Switzerland and New Zealand that aren’t in NATO or other formal alliance relationships but are definitely part of the western cultural milieu, but does not include Muslim NATO member Turkey.

But to test a hypothesis, you need to look at the boundary conditions. And Huntington’s “civilizational” account of conflict totally breaks down when you delve into the details of what’s happening here.

There’s no Orthodox bloc

Russia is really big and Eastern Orthodox Christianity has not had a ton of missionary success in the past thousand years, so the vast majority of the land area occupied by Eastern Orthodox Christians is in the Russian Federation. As a result, a map of Huntington’s Orthodox bloc looks very similar to a map of Russia. But if you zoom in, he posits that Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Cyprus, and Georgia should all be joining Russia, Serbia, and Belarus in the Orthodox Bloc.

Instead, those countries have all lined up with the West to levy sanctions. Now in four cases, that’s because these countries are part of the European Union and the EU sanctions are a collective entity. And Georgia is doing it because Georgia has a separate and longstanding conflict with Russia regarding Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

But these are the exceptions that test the rule. If Orthodox countries can join the EU, that calls into question the notion of a firm cultural dividing line between the East and the West. The EU has very clunky decision-making, and if the Orthodox Four strongly objected to sanctioning Russia, they could potentially prevent it. And the Georgia-Russia conflict stems from the fact that the Georgian government was pursuing NATO membership and integration with the West. Western countries turned out to be leerier of backing Georgia than they ultimately proved with Ukraine, but that’s because Georgia is geographically disconnected from non-Russian Europe, so it’s not perceived as a kind of forward defense of Poland and the Baltics the way that Ukraine is.

The other awkward thing for the “civilizations” theory is that the most pro-Russian country in the EU is Catholic Hungary, whose leader — Viktor Orbán — likes Putin. And of course lots of anti-EU politicians like Marine LePen in France and Matteo Salvini in Italy have ties to Putin. But this has nothing to do with civilizations. The EU is a big deal, so it’s natural for it to be a source of controversy in EU member states. And because European unity is bad for Putin, Putin cultivates support for anti-EU politicians.

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is proving embarrassing for his European friends, though, because despite specific complaints about the EU, the war underscores the fundamental value of European integration.

Ukraine is not much of a civilizational clash

It’s also worth noting that Huntington made a specific prediction about Ukraine, which he saw as a country that is “cleft” in civilizational terms between Orthodoxy and a more western-oriented Protestant/Catholic side.

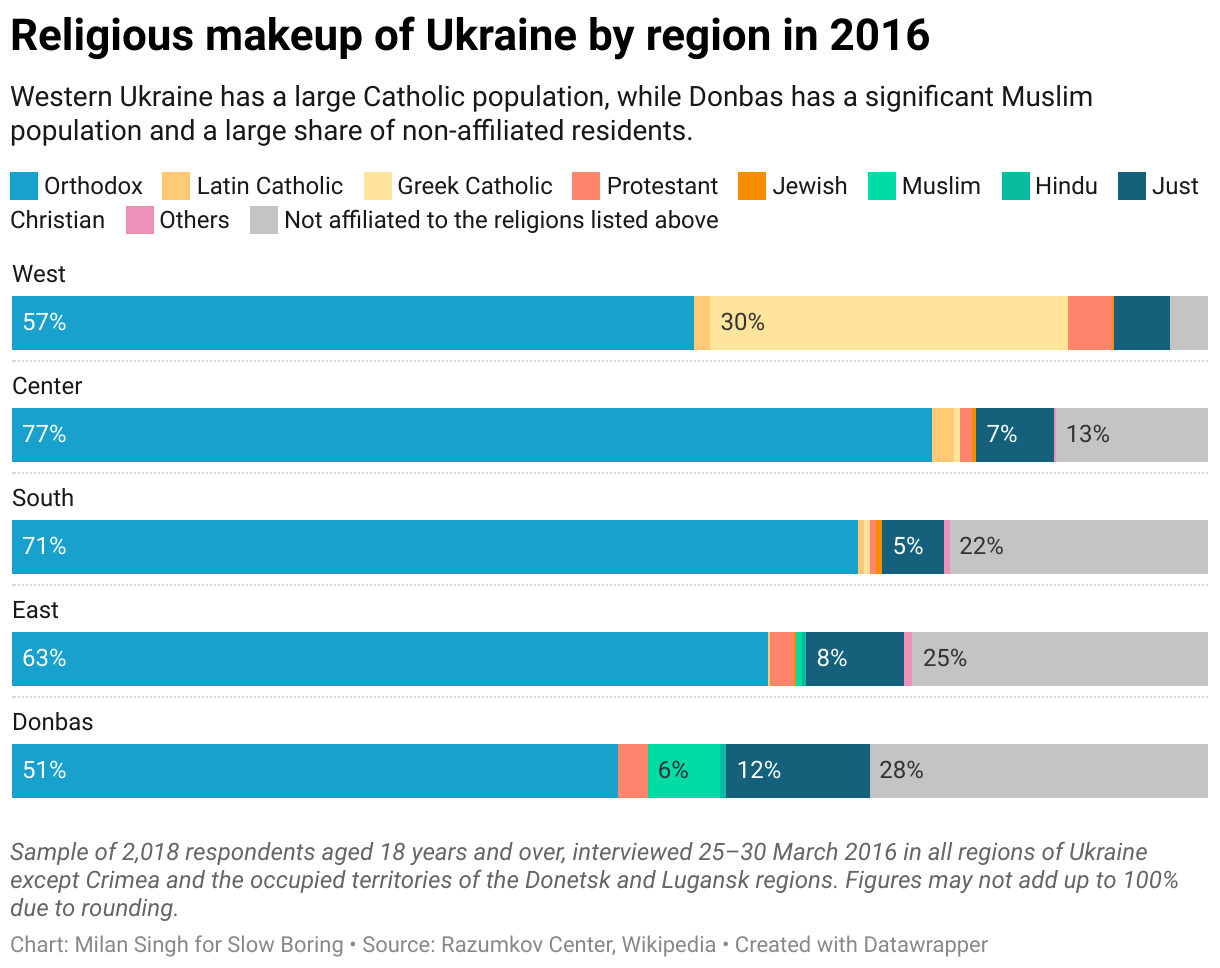

It is unquestionably true that Ukraine has historically been divided between Russian and western influences. Parts of contemporary Ukraine were governed from Warsaw or Vienna at various points, while others were under the sway of Moscow. In the eastern part of the country, lots of people speak Russian natively. In the west, lots of people are members of a Catholic church rather than an Eastern Orthodox one. But I think this internal divide actually undermines Huntington’s passion for dichotomies. You can certainly posit an ideal-type person who lives in Kharkiv, grew up speaking Russian at home, and practices Orthodox Christianity, or someone who is a Ukrainian-speaking Catholic who lives in Lviv.

But many Ukrainians don’t fit those neat categories. The vast majority of Ukrainian Catholics belong to Greek-rite churches, which have a lot of liturgical and cultural overlap with Orthodox Christianity.1 And there are lots of Ukrainian-speaking Orthodox Christians in Ukraine. Lots of Ukrainians are bilingual. And while there’s a regional element to the Ukrainian faith divide, all regions of the country are heavily Orthodox and the east actually stands out mostly for having more secular people than anything else.

Of course, low levels of religiosity are typical of Russian society as well. And the Russia-adjacent Donbas region’s relatively large Muslim minority is also a feature of the Russian Federation. Putin’s Russia, just like the Tsarist entities he looks back to, is a multiethnic polity with Chechen soldiers in Ukraine and a Defense Minister from the predominantly Buddhist Tuvan ethnic group.

So Ukraine fighting with Russia doesn’t map very well onto the Huntington framework. And the “cleft” portrayal of Ukraine, in particular, actually seems increasingly less relevant to understanding the current fight.

Ukraine is searching for The End of History

For the clearest depiction of Ukraine as a “cleft” country, look at the voting maps of the two elections that featured pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych as a candidate. In the first (2004), the Yanukovych-friendly incumbent regime tried to rig the runoff in his favor, triggering mass protests and the Orange Revolution.

That movement was largely portrayed in the West as a heroic good vs. evil battle for the sake of democracy, but the country was clearly deeply divided — largely along linguistic lines — and a few years later (with the help of Paul Manafort), Yanukovych ran again and won.

Ukraine was sufficiently “cleft” that Putin could achieve his core goals essentially within the confines of Ukrainian electoral politics.

But here’s where things went off the rails for Putin.

Ukraine was poorer than its EU-member neighbors and the gap was growing. And as Fukuyama would tell you, people everywhere have some basic similarities: namely, they don’t like being poor. And as I’ve written before, the path to riches for Ukraine was really clear: try to follow Poland, Romania, Hungary, and Slovakia into a closer trading relationship with Germany and enter the Germany-centric auto supply chain.

Poor countries that have deep economic ties to Germany and other Western European countries can get rich as low-cost suppliers of manufactured goods to the richer countries of Europe.

The top export of Poland is car parts (followed by cars), and the top destination is Germany. For Romania, it’s also car parts followed by cars, with Germany as the top destination. Hungary and Slovakia shake things up: there it’s cars followed by car parts, again with Germany as the top destination. Ukraine’s top export is seed oil, and its top trade partner is Russia. And the problem with being part of a Russia-centric economic system is that the Russian economy is based on fossil fuel extraction. Germany’s manufacturing economy can send supply-chain tendrils out to its neighbors, who start out manufacturing the lowest-value components and then move up. But there’s no value chain that Russia can export.

In February of 2013, under Yanukovych and with his allies enjoying a majority in parliament, Ukraine was poised to ratify an association agreement with the EU. Putin didn’t like that and pressured Yanukovych to make a deal with Russia instead. In November 2013 Yanukovych acquiesced, triggering massive protests and ultimately leading to the Revolution of Dignity, Putin annexing Crimea,2 and Russia sponsoring separatist rebellions in the Donbas region.

Since then, Ukraine has become steadily less cleft.

The pro-Russian faction lost power in 2014 when it became clear that the bar for being pro-Russian was “voluntarily abandon your best chance for economic development” rather than “have a lot of Russian-language shows on TV.” And that’s because the pro-Russian faction was ultimately controlled by Moscow and did not reflect the interests and aspirations of Russophone Ukrainians. That put the anti-Russian faction in the driver’s seat for years, but they didn’t do a great job of governing the country. That led to Zelenskyy’s landslide win in 2019, where he did much better in the eastern parts of the country than the west. Zelenskyy is a native Russian speaker, and part of his platform was to be more open to negotiating with Russia to end the conflict in Donbas.

This did not work (obviously), but its very failure successfully consolidated Ukrainian identity precisely because Zelenskyy’s policy initially was not seen as coming from a place of hardcore Ukrainian nationalism. What Zelensky was trying to give people was the basic ingredients of the end of history: good government, autonomy, and prosperity through integration with the richer parts of the world. In his own mind, Putin is surely waging some kind of battle for Russian civilization. But by shelling the cities of eastern Ukraine, he’s just confirmed to everyone that he doesn’t care about them — or really anyone — and that the way forward is to have an independent country on the road to EU membership.

Great power conflict is back

If you go back to Huntington’s map, one of the other things he asserts is the existence of a “Sinic” civilization that encompasses the People’s Republic of China along with Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam. He acknowledges that these countries do not have a warm relationship with the PRC, but asserts that the primacy of civilizational dynamics will prevail and lead them to bandwagon with China.

That’s an important point because, in broad terms, it can be hard to distinguish the Clash of Civilizations hypothesis from the more banal hypothesis that Russia and China are big important countries that don’t like to be bossed around.

But everything we’ve seen since the book was published looks more like the banal scenario than the civilizations one. Vietnam, despite not having much in common with the United States politically, is trying to align with us to protect itself from China. Korea and Taiwan, meanwhile, are clearly following Japan’s path toward integration with the West. You see that in their increasingly consolidated domestic democratic political systems. But also more broadly we had a Korean-language film win Best Picture at the Oscars, we have K-Pop global supergroups, we have Squid Game, and most of all we have these countries joining the West in sanctioning Russia.

And if you look at the non-sanctioners, what they have in common is not that they aren’t “western,” but that (unlike Japan, Korea, and Taiwan) they are poor and don’t want to make economic sacrifices for the sake of Ukraine. Meanwhile, of course, even Europe is still buying Russian natural gas. They believe strongly in the Ukrainian cause, but they also believe in keeping the heat on during wintertime. China is genuinely supporting Russia because China wants to have an ally. But most of the world, both western and non-western, is balancing a principled stand with practical material concerns.

The end of history and its limits

I think this all essentially reflects the basic logic of the end of history, which is simply that the prospect of economic and political integration with an ever-growing West is very compelling.

People in Romania and Bulgaria don’t want to be part of an Orthodox bloc; they want to be rich. People in Russophone Ukraine don’t want Ukrainian economic policy to be made for the convenience of the Russian government. Even if most people don’t have a particularly deep or principled attachment to democracy, they do care about their own interests. Most Russians’ interests are not represented in the Russian political system, which has let the government go off on a foreign policy adventure that is impoverishing its citizens. And even before the war itself, the Russian economy was paying a non-trivial price for its government’s determination to have a large independent industrial base and autonomous defense industry.

At the end of the day, Russia is awfully poor for such a big, empty country with enormous per person endowments of natural resources. In PPP-adjusted terms, it’s ahead of Bulgaria but behind Romania, Latvia, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Portugal. A Russia that was more integrated with the West, more dominated by efficient multi-national companies, and less inclined to waste resources on doomed efforts to compete with the United States would be much better off. Yes, they’d give up some autonomy in the warm embrace of post-historical liberalism and globalization. But Putin’s resistance is turning his country into an adjunct of China, not winning independence.

And just as Putin’s resistance meets a dead-end in China, so have liberalism and globalization. The PRC regime seems, if anything, much more solidly entrenched and repressive today than it did in the mid-1990s. China has also become much wealthier and more capable, manifesting none of the cultural bandwagoning that Huntington predicted but nonetheless achieving steadily rising living standards, all without conceding anything to liberalism. And that is where 1990s-style optimism about the future of democracy hits a dead end.

The PRC is a fundamentally more formidable entity than Putin’s Russia, and I think we’re a long way from getting a grip on what to do about it.

I’m going to admit to being pretty fuzzy on how this actually works … I read a Wikipedia article about it, but it seems weird.

This has, of course, had the unintended effect of weakening pro-Russian groups’ electoral strength in Ukraine.

For anyone confused by Eastern Christianity: As an Arab guy in diaspora, I have spent a lot of time hanging out with both Eastern Catholics (mostly Maronite and Chaldean, but also some Coptic Catholics and Greek-rite Melkite Catholics) and Orthodox (mostly Coptic, but my roommate sophomore year of college was an Eastern Orthodox Palestinian), even though I’m neither myself. This is the distinction I’ve found (mostly from that roommate, who ended up getting a degree in theology):

"Catholic" v "Orthodox" is about polity, i.e. who gets to call the shots in the church. More specifically, it’s whether you think the Pope is the Top Christian and everyone (who's Christian) should listen to him, or if he’s just the Patriarch of the Latin Church who deserves respect but is just another top prelate among many others.

The rite thing is about what you actually say and do in church. It turns out the Pope doesn’t really care what you actually do in church day to day as long as you recognize him as Top Christian and doesn’t deviate from Church doctrine. Eastern Orthodoxy has pretty much exactly the same doctrine as Catholicism outside of the pope thing (and maybe the filioque), so all an Orthodox church needs to change to become "Catholic" is say "ok we recognize the Pope as Top Christian now" and they’re now Catholics. But if you walked in, you’d be forgiven if you thought they were Orthodox. ("Rite" is usually also about liturgical language, but ever since the Vatican II switch to the vernacular for Latin-rite churches, this distinction is a bit blurrier.)

NOTE: None of this addresses Eastern v. Oriental Orthodoxy, which is a whole 'nother can of worms.

“The PRC is a fundamentally more formidable entity than Putin’s Russia, and I think we’re a long way from getting a grip on what to do about it.”

For the moment, allow its own internal contradictions to play out while we prevent it from playing conquistador in East Asia.

There’s no way to know exactly how the current challenges facing the Chinese state, and the interplay between a citizenry that’s come to expect quite a bit of economic freedom and yearly improvement and a centralizing, totalizing state will play out, so let’s not try just yet.

The current posture taken by the US is probably close to correct as a holding pattern, so long as we can get Germany to be serious about its role and that of the EU.