Two cheers for American higher education

Let's subsidize community college and crack down on scams, but American college finance has big successes

I was thinking of writing yet again about student debt cancellation, but I think it’s more important to take a step back and consider the pro-cancellation camp’s broader issues with the whole student loan system than to continue the argument about one-off cancellation.

And here I absolutely agree there are problems (see “There Are Too Many Scams in Higher Education”). I also think the extent to which things are systematically better in Europe thanks to more generous subsidies is generally overstated. The subsidies in Europe are more generous, which absolutely does contribute to the lower tuition. But the aggregate spending volumes are also lower, the college experience is crappier, fewer people enroll in college, and Europe is much worse at cultivating excellent universities.

I often find myself somewhat at odds with Leftist College Professor Twitter over higher education issues, but I have no sympathy for the rightists who hate the college professor community so much that they want to tear American higher education to the ground. Leftist Professors, being leftists, don’t like to say nice things about America or the virtues of our more market-oriented higher education sector, but surely they’ve noticed that the net flow of Leftist College Professors is from Europe to the United States. Our schools have more money — in part because they are empowered to charge high tuition, which students can afford because of loans — and this allows them to hire many of Europe’s top Leftist College Professors, which is a big reason we have the best universities in the world.

There is more to life than the tippy-top of the education distribution and there are some real areas for reform and rebalancing in the United States higher education space. But some of the policy ideas I used to routinely offer — like making subsidies more evenly spread across types of institutions — are now happening, and the situation is getting better.

Fundamentally, though, I do feel bad for the large cohort of college graduates who are a bit younger than I am. I was born in 1981 at the very beginning of the “millennial” wave. I graduated college in 2003 and settled into a career quickly, so by the time the economy collapsed in the winter of 2008-2009, I was on the ladder. But if you look at the cohort just behind me, the demographic bulge is larger and people had their early career years either derailed by the Great Recession or else they graduated into a crappy labor market. That’s an awful, scarring experience. It was awful for the people in those cohorts who didn’t go to college, and it was awful for the college graduates. And it created this “student loan” discourse that I think on some level is really about the horrible macroeconomic management that allowed a weak labor market to persist for nearly a decade. The actual higher education issue looks pretty different in today’s stronger labor market — especially if we adopt a more realistic view of European higher education practice.

Student loans are a form of subsidy

It’s important to recognize that student loans are a subsidy to students and to colleges. The typical framing from the left is to characterize student debt as a deficit — a deficit that should be filled by direct government subsidies. But the student loan program is itself a subsidy relative to a pure market system. It allows people to spend more on college tuition than they would otherwise be able to spend. That helps some people be able to afford college who otherwise couldn't afford it.

But it also allows schools to raise their total spending (and therefore tuition) over what would otherwise be possible. And I think we see that this is what happens. I’ve been to the campus of the University of Minnesota and also to the campus of the University of Helsinki which is the top school in Finland. Finland and Minnesota are about the same size, and Minnesota’s appropriation to the University of Minnesota is about the same size as Finland’s subsidy to the University of Helskinki. But Minnesota has twice the number of undergraduates and about three times the staff. It also has a nicer campus — starting with the fact that it’s a coherent campus instead of being scattered across four different clusters in the Helsinki area.

If you add it all up, University of Minnesota’s average annual budget of $4.2 billion dwarfs the University of Helsinki’s 703 million euros.

So while a person might take the position that Minnesota should simply cut a much larger check to its flagship university than Finland does, in practice copying the Finnish approach would mean shrinking the university and making it more austere. What American higher education lacks in direct appropriations, it more than makes up for with credit and tax deduction programs that funnel additional private resources into the higher education sector. If you look across the G7, you’ll see that despite our relatively paltry direct higher ed spending as a share of GDP, we send a lot of kids to college.

You can also see that America’s college completion rate isn’t great. That’s not the only driver of the gap between enrollments and final attainment (there’s a lag based on older, less-educated cohorts and Canada boosts its numbers with a heavily skills-focused immigration system) but it’s an issue that we’ll return to.

For now, though, the point is just that on the high end — by which I mean not just the Ivy League but flagship state universities, too — our system allows for generously funded schools that are the envy of the world.

High-end American higher education is really good

Boris Johnson’s government recently rolled out an initiative to let recent graduates of the world’s top universities move to the UK. That required them to come up with a definition of the world’s top universities. Of the 38 on the list, a staggering 20 are American. And while it’s true most of those are private (though private schools benefit from student loans and are not outside the ambit of American higher education funding), there are six US public universities on the list versus five European universities. There are five California universities on the list (Stanford, Caltech, and three UCs) versus one from Germany.

This is really good! Of course, not every American public flagship university is as good as UT-Austin, the University of Michigan, or UCLA. But the states themselves pursue a variety of strategies with regard to their systems. In Wyoming, for example, the in-state tuition is really cheap.

And that’s because, as you’ll see here, Wyoming is one of the most generous public higher ed funders around. Vermont, on the opposite side of the spectrum, is very stingy with subsidy and has high tuition.

But note that tuition doesn’t correspond mechanically to subsidy. Florida has low tuition and low subsidy. Both the California model of excellent public higher ed and the Florida model of “cheap, good enough” higher ed seem like plausible ideas. Texas is somewhere in the middle. There are plenty of states that may have landed at bad points on the tradeoff curve, but these are the three biggest states, so that’s pretty good.

What we have a relatively decentralized system with a good amount of competition and that generates pretty good results. But there is a fly in the ointment.

The basis of competition

A big issue with competition in the higher ed marketplace is that very little emphasis is put on trying to measure how much students learn in school versus how smart are they when they graduate.

But the quality of your graduates is a mixed function of the quality of your educational programming and the quality of the students you have to work with. The graduates of the UT Austin campus are on average smarter than the graduates of the UT El Paso campus in part because Texas is harder to get into than UTEP. It would require a shocking failure of the educational programming to not end up with better outputs. So when schools try to compete and get “better,” in practice that means trying to get better freshmen, not do a better job of educating the freshmen they have.

That means if a pile of money lands in a school’s lap, the operative question is “what will make the students we want want to come here?”

And that could mean all kinds of things. Over at the University of Alabama they have an outdoor pool complex that “features a lazy river, splash pad, kiddie pool, water slide, and the Bama Cabana for refreshments,” which sounds awesome but seems like it has questionable educational value.

Now, again, at the highest end, the incentives probably actually are pretty aligned — if you’re trying to get the very best students, you want to invest in things that sad nerds enjoy, like really good libraries. One of my favorite things about Harvard was the great speakers and fellows they brought to the Institute of Politics; I also got to play SimCity with the former mayor of Cincinnati and get pizza with HHS Secretary Tommy Thompson and ask him about Bush-era Medicare reforms.

But because anything that is in the bundle labeled “college” is eligible for student loans, there is definitely an incentive to roll a lot of stuff into the bundle. If tuition gets you into a campus gym, then students loans are covering your gym membership. Absent loans, the incentive is to make the bundle skinnier. You pay tuition for what only a college can provide. If you also want a gym membership, then you go buy a gym membership.

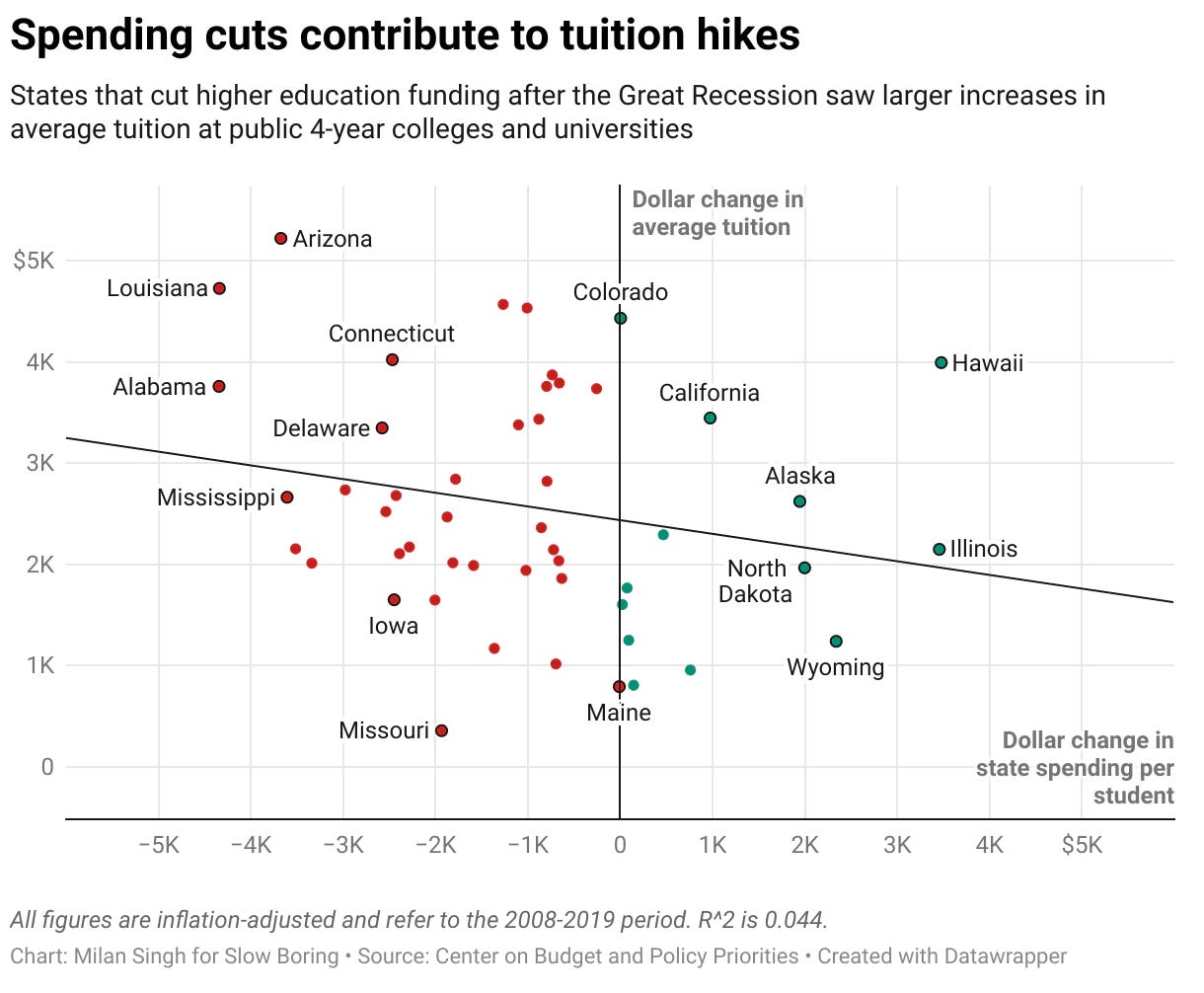

There’s also a lot of talk about administrative bloat in this context. But one man’s bloat is another’s vital campus program. The University of Minnesota has a nine-person Office for Equity and Diversity led by Vice President Michael Goh; the University of Helsinki has an Equality and Diversity Committee led part-time by the Vice Rector of the University and featuring one full-time staffer from the HR office. Is this waste or is it important? You can probably guess my opinion. But regardless of what I think about the office, this stuff exists because someone wants it. I’ve posted this chart before, but we can see that while there is a statistical association between state investments in higher ed funding and tuition trends, it’s a pretty loose association.

And that’s because tuition-setting is genuinely a complicated calculus. Separate from any question of state subsidy, Minnesota clearly could make tuition a bit cheaper by firing the diversity office. Or they could make tuition higher and build more cool swimming pools. They could try to hire more star faculty. Or they could get stingier with their faculty offers and risk losing out on more talent to private schools.

I don’t have a sweeping judgment here about what’s right or wrong, just the observation that if you plow more subsidy into a college that is already enjoying robust demand, the natural reaction is to spend the money, not cut the price. If you want the price to be lower, you need to demand spending discipline. But it’s not obvious that should be the priority if people are willing to pay the existing price.

Breaking down the college bundle

I’ve been talking about flagships, but of course there are all kinds of public schools.

And one interesting thing you can see in the College Board data is that both spending and price trends are very different at different points in the prestige hierarchy and there are also differences in rates versus levels. The institutions that grant doctoral degrees get the most subsidy, but they charge the highest tuition. And that was true even before a decade of spending cuts pushed them to charge even more.

By contrast, lower-end schools that offer only a bachelor’s or an associate’s degree charge less tuition despite receiving less subsidy. But their level of subsidy has been rising for the past ten years, and while tuition hasn’t fallen, it has at least stayed flat.

This seems like a good trend and has forced me to update my opinion about subsidies since things have changed from the circa-2009 fact pattern of massive inequality. I’m glad to see the gap narrow so much, and if I were in charge of a state’s higher education policy, I would fully close it so all institutions receive the same per student subsidy. There would then be an understanding that the low-end institutions should charge very low tuition and be relatively austere, while your top research universities are free to try to charge people high tuition if they are willing to pay for the extra spending.

Fundamentally, I think the idea of trying to subsidize down the tuition at the top schools doesn’t make much sense because at the current prices, these schools are already hard to get into. Nobody is forcing you to go to the most expensive university in the state. Making sure the cheap schools stay cheap and decent to provide an alternative is a good investment. But subsidizing the best schools into cheapness would be wasteful, and mandating that they stay cheap through austerity would undermine excellence. I’m trying to stay out of the debt forgiveness hornets nest, but this is where we do see a mismatch between reality and the discourse — the people most empowered in the debt debate are graduates of good colleges, but those people are clearly benefitting from the opportunity to attend a selective school even when you consider the impact of debt. The people being poorly served by the system are the people attending (and often not graduating from) much worse schools.

Focus on the low end

I always thought the Obama administration had basically the right idea: a school that is routinely enrolling students who end up earning so little money that they can’t make payments on their loans ought to be cut off from the student loan program.

In order to avoid angering his political allies, Obama structured this rule so as to only apply to for-profit schools, which really were massively overrepresented among the bad actors. Then Betsy DeVos took office and made the reasonable point that excluding non-profits was an unfair form of bias. But instead of applying the same rule even-handedly, she scrapped the rule. Since that time, a lot of bad for-profit education providers have become contractors. Today, instead of enrolling in a crappy online-only for-profit degree program, you can enroll in an online-only degree program from a reputable nonprofit institution — except the program will be crappy and run by the company that used to run for-profit schools, now a for-profit contractor for a non-profit institution.

This is really bad and we ought to stop it. But note, again, that increasing the level of public subsidy to the worst actors in higher education is not the solution to the portion of the debt problem that looks like “I got taken-in by a scam.” We might want to help the scam victims ex post, but the main policy priority has to be shutting down scams.

It’s also worth saying that these low-end problems are almost certainly alleviating. The supply of teenagers is currently dwindling at a time when the labor market is really hot, so bad schools are facing increasingly fierce competition. As I said at the top, I think that in the fullness of time we’ll see the “student debt crisis” as mostly a tragic conjunction of demographic luck and bad macroeconomic stabilization policy and actually not a higher education policy problem at all. We should absolutely act more forcefully to crack down on scams, but the teen employment boom combined with selective schools getting less selective for demographic reasons will be a crackdown all of its own.

American universities were able to hire the best and brightest long before very high tuition engendered by subsidized student loans became available.

In fact, they not only did that, but also hired a great number of “merely“ talented teaching professors and lectures as well.

In the era in which they’ve transitioned to student loan-driven tuition increases as a model for funding, they have instead squandered vast sums of money on useless shit, at the same time is cutting stable professor and lecture positions in favor of adjuncts paid peanuts.

The entire current student loan system needs to be done away with, and the massive administrative and lifestyle bloat that it allowed needs to be extirpated root and branch.

The only “someone” who wants this shit is the bureaucracy staffing it.

We have too many kids going to college and too few going to trade schools or directly into the workforce. The result is an over-educated, under-skilled populace, and many of those people are now earning too little to pay back their loans for their education.

Until we stop sending the message to the vast majority of high school students that they should go to college, this problem won't be solved regardless of any loan forgiveness program.