Trump's tariffs mean big opportunities for corruption

The White House will be picking winners and losers

I didn’t write about tariffs or trade policy in Monday’s post on the economic implications of a GOP sweep in November. That’s in part because, to the extent any policy issue has been debated in the 2024 campaign, it’s been tariffs. But it’s mostly because I wanted to focus on legislation, and the weird thing about tariffs is that the structure of American trade law gives the president broad authorization to raise tariffs without any new act of Congress. A lot of this was set up in an earlier political context, when the broad assumption was that presidents would rarely want to raise tariffs. And for a while when Trump was president, I thought his enthusiasm for tariffs might thermostatically push Democrats in favor of free trade and create some bipartisan support for rolling back executive branch unilateralism in this area. Instead, Democrats themselves piled onto a backlash against “neoliberalism,” and Biden has largely kept Trump’s tariffs in place.

Now, though, Trump is promising to come into office and implement a 10 percent tax on all imports, plus a higher tax on all imports from China.

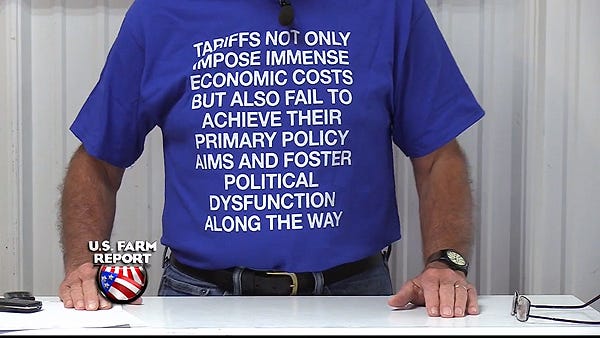

This t-shirt, designed by Scott Lincicome who does trade policy at the Cato Institute, offers a pithy criticism of Trump’s proposed tariffs:

I’ve written several times about the “immense economic costs” aspect of this, including higher consumer prices and higher interest rates. There’s also the part where you “fail to achieve their primary policy aims” because taxing imported intermediate goods hurts American exporters. If US-based factories need to pay higher prices for foreign-made gaskets, that becomes a reason to put the whole factory in Mexico, where they can get the cheap gaskets. It’s fine to say we should reject laissez faire dogmatism and come up with some kind of industrial strategy, but “higher taxes on everything” is not much of a strategy. If you raise these concerns with conservatives who know what they’re talking about, they promise that the actual policy will be more nuanced than that. Trade war enthusiast John Carney was telling me the other day that Trump’s tariffs won’t really lead to soaring berry prices because most berries the US imports come from Mexico,1 and Trump wouldn’t want to jeopardize his signature USMCA trade deal by applying his 10 percent tax to imports from Mexico.

Maybe? But this is where the political dysfunction comes in.

Tariff exemptions with an honest, non-corrupt president

It’s frustrating to argue about Trump’s policy ideas, because two of his defenders’ go-to talking points are “Donald Trump is a huge liar” and “Donald Trump has no idea what he’s talking about.” Any time you construct an argument of the form, “Trump says he will do X, the consequences of X are likely to be Y, and Y is bad,” they respond with some version of the old saw about how you need to take Trump seriously, not literally.

That said, it is true that while Trump never says this on the campaign trail or in any of his official policy material, the reality of tariff policy is that what the executive branch unilaterally giveth, the executive branch can (and does) unilaterally taketh away. So whatever sweeping tariffs he imposes, he will also grant exceptions.

During his previous term, Trump imposed tariffs on China that were modest in scale compared to his current proposals. Nonetheless, after imposing those tariffs, he granted hundreds of exemptions in response to thousands of waiver requests from American companies. This is, officially, a way to be responsive to the concern about failing to achieve the primary policy aims. Trump, for example, exempted certain parts of swimming pool vacuum cleaners from the tariff regime, along with “electronic scales for continuous weighing of quartz, powder and resin on conveyors” and “aluminum radiators for motor vehicles.” These are things that you use to make other things. And you are allowed, as a company, to go hat-in-hand to the Commerce Department and say, “Hey, look, to run my company I need some electronic scales for continuous weighing of quartz, powder, and resin on conveyors, and the only makers of the appropriate kind of electronic scales are based in China, and if I need to pay high taxes on my scales then my whole company will be disadvantaged relative to foreign competitors who are taking advantage of cheap Chinese-made electronic scales for all their weighing of quartz, powder, and resin on conveyors.”

As stated, that sounds like a perfectly cogent argument for granting the exemption.

But I personally have no idea what an electronic scale for continuous weighing of quartz, powder, and resin on conveyors really is or what the market for such scales looks like. Suppose some American scale company tells me they, in fact, do make electronic scales for continuous weighing of quartz, powder, and resin on conveyors and the waiver should not be granted. But then the waiver applicant responds that it’s not the right kind of electronic scale and that being forced to use this misaligned scale will wreck their business. And then the scale maker says of course his scales will work fine, it’s just that the lazy applicant doesn’t want to retool his application.

This policy essentially forces the Commerce Department to turn itself into a little central planning office for the American economy. And even if you assume perfect good faith on the part of all the political appointees and career staff,2 it’s not reasonable to expect them to do a good job making all of these technical decisions.

The existing Trump/Biden tariff regime is relatively mild, so the burden on the bureaucracy is relatively mild, and the amount of political dysfunction is also relatively mild. It also, at least kinda sorta, has a foreign policy rationale that is comprehensible and widely shared, though even under the status quo you see plenty of cracks. Last week the Biden administration announced new penalties on importing certain metals from Mexico, because they said the metal in question is actually Chinese metal being routed through Mexico to avoid tariffs. This is a plausible worry, but it’s another example of how effectively implementing a protectionist trade regime requires detailed industry-specific knowledge. Attempting to impose this level of scrutiny on every industry simultaneously means putting incredible faith in bureaucratic management of the economy.

The politicization of everything

If you dramatically increase both the scope of tariffs — applying them, as Trump says he will, to all categories of goods from all countries — and also the scale of the tariffs (as Trump says he will on China), you dramatically raise the stakes of this kind of showdown.

And, of course, political considerations inevitably enter into the mix.

I started with the example of the electronic scales for continuous weighing of quartz, powder, and resin on conveyors, because that sounds on its face like a legitimate example of a specialized intermediate good that American companies really need access to. It’s also quite obscure. But lots of stuff that’s made in China is not obscure. Apple, for example, is an incredibly high-profile American consumer goods manufacturer that relies on Chinese manufacturing for a large share of its products. Some of that is final assembly based on China, but a lot of it is reliance on Chinese-made components for products that are very complicated. I am not a Republican, so I actually think raising the price that Apple’s upscale consumer base pays for its various gadgets is not the worst idea in the world. Accomplishing this via tariffs is roundabout and inefficient compared to a proper tax regime, but I’m not going to cry for Apple superusers.

But it’s a high-profile company, and as Republicans know, middle class people don’t like to pay higher taxes. During Trump’s first term, he initially vowed that Apple would get no exemptions in the spring of 2019, but then in the fall, there were a lot of stories about how prices on Apple products might go up. By September, Apple was winning limited exemptions. Then, in December, Trump reached a “Phase 1” trade deal with China, which was used as a pretext to exempt iPhones, and in March 2020, Apple won an exemption for Apple Watches, too.

Any highly discretionary process becomes political.

Theoretically, the waivers are granted on a technical basis. But there’s only so much capacity to do technical and legal analysis from scratch. In practice, agencies are relying in part on the strength of the cases that are submitted to them by the people making the requests. Some of that is the actual strength on the merits, but some of it is the quality of the lawyers and lobbyists these companies can afford to hire. And, of course, if your company is in a swing state or has close ties to a member of Congress the White House cares about or (like Apple) is salient in the media, other people start getting involved in the meetings to decide what should happen. You can be optimistic that a well-run administration won’t let political considerations run roughshod over everything else. But realistically, you can’t take the politics out of politics. In a discretionary process, the interests of companies with political clout will be weighted more heavily than those of outsiders or startups. And companies will need, at the margin, to shift their time and attention to the process of getting waivers and away from making good products.

Bringing Trump back in

And when it comes to Trump we’re clearly not just talking about much higher tariffs than under Biden — we’re talking about an administration run by Donald Trump.

Trump is not a bloodless technocrat or a policy wonk who’s going to insist that every one of the thousands and thousands of waiver requests that come through the Commerce Department should be evaluated strictly on the merits. Trump’s supporters say he’s a showman who places a high value on loyalty and public relations and doesn’t really care about details or the merits of policies.

In his hands, this is going to be an orgy, not just of politicization, but of corruption.

He’ll be able to deny waivers to companies with too many employees who donate to Democrats, or grant them to companies that funnel money into his hotels. One of the big plot lines of the first Trump administration was that the bulk of the personnel working for him were more-or-less generic Republicans, many of whom ended up having various fallings-out with their new leader because they didn’t want to follow his illegal orders. There’s been a lot of discussion of various policy proposals associated with Project 2025, but the main thrust of the project as I understand it is an effort to pre-screen potential job-seekers for loyalty to Trump. The reason John McEntee is in charge of it is his personal relationship with Trump. The point is to build a state apparatus that is as amenable as possible to misuse.

Over the past year, I’ve seen a lot of business types develop new respect for Trump, and also get really enthusiastic about Javier Milei in Argentina. And I do get that Milei has strong Trump-like vibes. But realistically, if you want to understand the economic policies that wrecked Argentina, it’s not anything to do with the welfare state or environmental rules or other normal progressive stuff. What started as a little effort at protectionism and industrial policy sprawled over the years into a vast web of clientelism and patronage, where political connections determined who could do business and on what terms. Over the course of a single four-year term, the damage would likely be limited (though Trump would probably reap a lot of bribes), but it risks entrenching a whole new way of doing economic policy in the United States, one in which presidential grace and favor is the key to doing business.

The USDA’s Economic Research Service does not actually have a “berries” category. But for the record, 98 percent of imported blackberries and 99 percent of imported raspberries are from Mexico, but only 20 percent of strawberries and 33 percent of blueberries.

Recall that Trump is also planning to politicize civil service hiring, but that’s a story for another day.

I completely understand the case Matt is making here. Trump is corruption made flesh. But I want to provide a good, honest, neoliberal shrill reminder that even *honest* trade tariffs are quite bad. When Americans buy stuff from foreigners, they typically do so because it's cheaper. Thus tariffs require Americans to pay more. This mechanically reduces incomes, and makes us poorer. It also reduces the productivity of the economy, by forcing us to shift more capital into obtaining inputs than would be the case without the tariffs (which leaves less capital for everything else). So it's a double whammy: poorer immediately, and poorer and economically weaker over the longer term, because of the hit to productivity and efficiency.

We no doubt do need a measure of industrial policy to ensure we can produce things like artillery shells, warships, attack drones and the like. And given the hostility of China, that list probably has to include things like microprocessors and pharmaceutical precursors.

But, really, we ought to be doing the minimum amount of trade restricting consistent with our national security needs. I remember thinking, shortly after the 2020 election: "Democrats in Congress ought to take advantage of this window to narrow the scope of the executive branch's power to restrict foreign trade." Pity they didn't. And too late now.

Great issue to highlight. Since the free-trade consensus is dead, and a tarrif heavy system is also bad as you point out here, I wonder what a better system look like? It would be great if we could achieve a bipartisan consensus that friend-shoring is a good idea, then the limited tarriff regime could be focused on China and paired with subsidizing domestic production and/or production in friendly countries.