Unleash the trailers

It's time to end regulatory discrimination against manufactured housing

In America’s most expensive housing markets, the dominant cost feature is the land, not the actual construction of buildings. So I’ve never written much about the bizarrely low (and by some measures, falling) productivity in the construction industry. In the markets where we have the biggest problems, better construction isn’t what we need — our existing construction is “good enough,” and just allowing more of it on the priciest parcels of land would be great.

That said, the poor productivity performance is interesting. And it does matter for housing affordability in the cheaper parts of the country which, after all, is most of the country. And while the overall issue is complicated, there does seem to be one fairly simple solution for kickstarting change — ensure total regulatory parity between small single-family homes built in factories (“trailers” or “mobile homes”) and stick-built single-family homes.

Technology enthusiasts sometimes go around the bend touting the benefits of modularization to change everything about the construction industry. Austin Vernon has a great post detailing the roots of cost issues and rightly, I think, pouring cold water on the idea of a huge breakthrough here. It’s worth your time, and I obviously agree with the bottom line that zoning is key. But I also think he is underrating the possibility that land reforms could drive further technological improvements.

Way at the end of his post he delivers this as point two:

Trailers already cater to cost-conscious consumers. They are cheap at $50 per square foot. Eliminate the zoning regulations that restrict new trailer parks. Allow buyers to finance trailers as regular real estate. If the government subsidizes 30-year mortgages for well-off buyers, extend the same to trailer buyers. Better yet, remove all that involvement and level the playing field. If trailer sales increased, factories could be more numerous and closer to markets or increase volume, lowering costs

This is right on, but I think Vernon is missing an important regulatory disadvantage facing small manufactured homes (“trailers”) and is to some extent downplaying the significance of unlocking them for wider use.

Some terminology that is important!

Because I grew up in Manhattan, for the longest time I thought a “mobile home” meant an RV — like the idea was you would drive it around.

Obviously, RVs exist. During the Great Depression, when the country was experiencing severe economic hardship, it was also semi-common for families who’d lost their land or their livelihoods to be reduced to living in “trailers” — small accessory vehicles that you could drag around the country behind your car while searching for work.

Both of these terms convey a sense of itinerant that makes them seem inherently undesirable as permanent habitations.

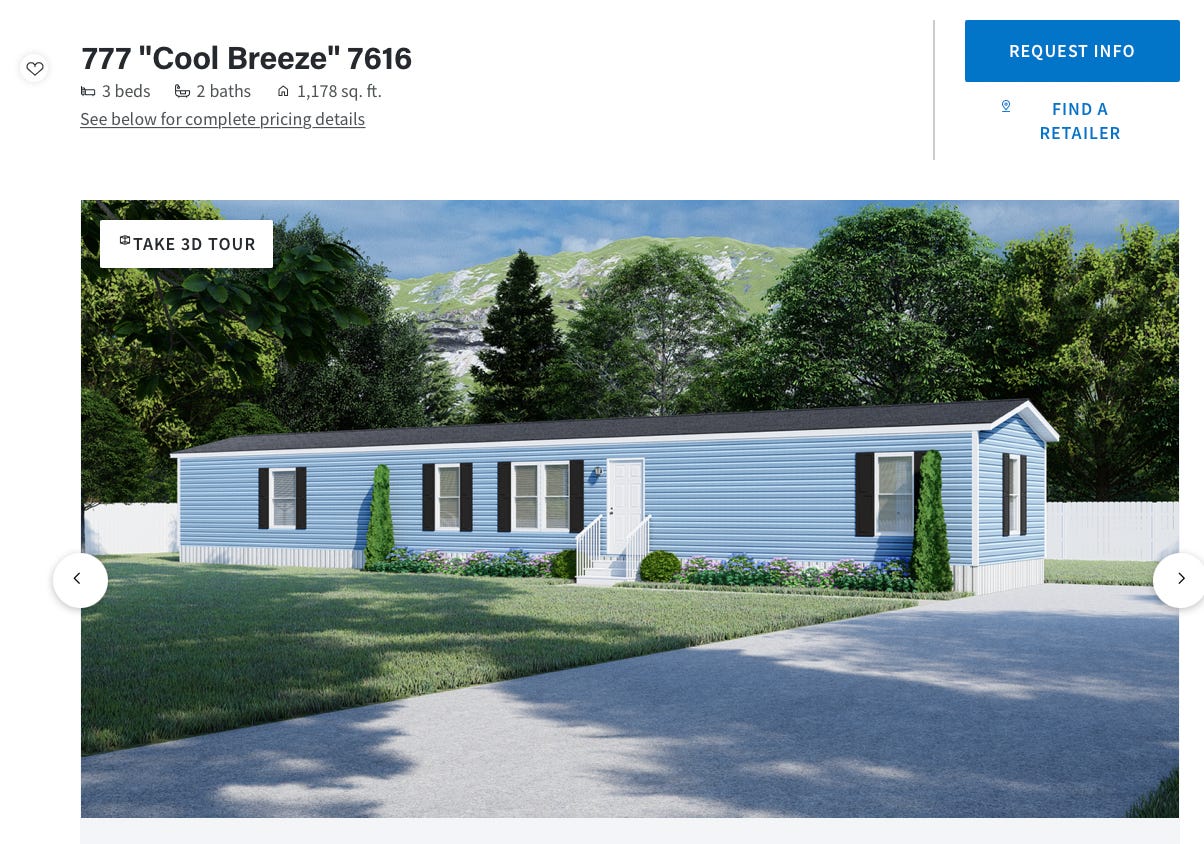

Something like this from Clayton Homes, by contrast, is clearly not supposed to be moved around. It’s just a regular small house. The difference is that it’s built in a factory and then delivered to the site where you plop it down.

This is the cheapest way to build a home. And because it’s the cheapest way to build a home, homes that look like this are inherently “cheap-looking,” and people who have money will normally pay a large premium in order to get a home that does not look like this. That being said, if you don’t have a lot of money or are oblivious to snobbishness, it’s a perfectly good place to live with very cheap construction costs.

I’m going to call this a small manufactured house.

Then there are larger manufactured homes like this one from GoLogic where you can’t move the whole house. Instead, you build a bunch of panels in a factory then you move the panels to the site and you build the house there.

Last but not least, you can have a custom manufactured house where it’s done as panels in a factory, but rather than buying a preset home plan, you work with a designer to create a custom set of panels that are assembled on site. GoLogic does that too.

Architects have gotten really interested in these high-end prefab concepts and Dwell magazine likes to write about them, so when you see commentary on the topic of prefab, it often focuses on the high end. Here, though, I think Vernon’s diagnosis is correct. The dream of prefab drastically reducing the construction costs of custom homes sounds really cool, but it does not match the reality. If we are going to see disruptive changes in home construction, it’s more likely to come from the low-end.

High-end and low-end change

For a while, everyone in the technology industry loved talking about Clayton Christensen’s concept of “disruption.”

His idea is that oftentimes, companies get really, really, really good at serving their existing customers, and really, really, really focused on endlessly upselling them on more and more stuff or more elaborate customizations. Then some new player comes along with a product that’s half as good at a quarter of the price. But the old player is focused on his existing customers and says to them “you don’t want the competition’s half-as-good garbage.” And mostly, they don’t. But some new customers who weren’t served by the old expensive product start buying the new cheap one. So the incumbent doubles down on serving the high-end of the market and congratulates himself on his high margins.

But over time, the cheap new entrant gets better and better and starts eroding the incumbent’s market share. Yet the incumbent is so attached to his existing customers that he fears introducing any new, cheaper products to compete with the entrant because they’ll cannibalize his existing sales. Next thing you know, the incumbent is on the ash heap of history.

This is a good story, and it’s sometimes how things work. But then along came Elon Musk, who became extremely rich by reminding everyone that things can also work the other way.

Tesla’s big idea was to make an electric car that was really, really awesome and would appeal to people with gobs money who don’t care about value at all, but just want a great car. This time the naysayers concede that the car is cool, but they point out that cars are a mass market. You can’t build a car company just around people with silly amounts of money to spend. But Musk uses his super-rich customers to accomplish three things:

Through learning-by-doing, they get better at making the Model S, and costs go down incrementally.

The Model S is the customer base for a nationwide network of high-quality EV charging stations.

Through learning-by-doing, they get better specifically at making the kind of batteries they need, with batteries being a general-purpose component of any kind of electric car.

Then you start taking your improved battery capabilities and use them to build the Model 3, a car that is less awesome than the Model S but a more plausible value proposition for a much larger set of economically comfortable people. And the 3 can also use the supercharger network. So now you have an electric car that, while not cheap, isn’t outrageous either. And the superchargers address normal people’s biggest concern about electric cars. Next thing you know, Musk is so rich that people are getting mad that we don’t tax unrealized capital gains.

The Dwell People keep hoping for an Elon Musk of prefab housing, but it keeps not working. The big problem is that while making modules in a factory and shipping them to the site could be a lot cheaper than building on-site from scratch, you need to operate at a massive scale to achieve those gains. You need factories running at full capacity and delivery distances that aren’t too arduous. That means you need tons and tons of demand for the panels. At the start of the process, you’re not at that scale, so your cost advantage is illusory. At this point, the problem with high-end prefab is that while it’s interesting, it’s not obviously better in a way that would make lots of people want to buy them.

But at the low end, we are just dealing with regulatory barriers.

Regulations cripple small manufactured homes

Most of the Zoning Discourse is focused on big cities and barriers to multifamily construction.

But it is very common for jurisdictions to draw a zoning distinction between a manufactured single-family home and a stick-built single-family home. See Daniel Mandelker’s “Zoning Barriers to Manufactured Housing,” the 2011 HUD report “Regulatory Barriers to Manufactured Housing Placement,” and various state-level reports like “Local Land Use Regulation of Manufactured Housing” or this report on zoning from a manufactured housing trade group.

This is just a straight-up financial penalty on low-income families with the benefits flowing to homebuilding companies who benefit from the lack of competition. It’s the rural/exurban equivalent of bans on multifamily housing in cities and inner-ring suburbs, but without even the fig leaf justifications related to noise and traffic. We’ve made housing more expensive than it has to be by, in some areas, banning the use of the lowest-cost form of housing.

There are also some more subtle issues. James Schmitz from the Minneapolis Fed has done a lot of work on this topic. I found his latest paper on this to be a little confusingly organized because he chose to frontload a somewhat idiosyncratic definition of “monopoly,” but the guts of the paper explain a regulatory scandal. During the postwar boom in manufactured housing, the typical practice was to mount a small manufactured home on a chassis to transport it to its destination and then remove the chassis and place the home on a foundation or even on top of a basement. Then came a federal crackdown on manufactured housing designed to benefit homebuilders, which requires that the chassis not be removed:

The permanent chassis requirement has a significant negative impact on the industry. First, by requiring a chassis, the regulation endeavors to make the small modular home resemble a trailer, linking the prejudices of trailers with small-modular homes. Second, since the house has a chassis, local zoning laws can often be applied to block it from the local area. Third, since it has a chassis, it’s argued that it can be moved (though they aren’t moved), so that the houses are financed as cars (with personal loans) and not real estate. Fourth, the regulation increases the cost of manufacturing the house.

In other words, a small manufactured house is disfavored because it’s mobile like a vehicle but it is also required by law to be mobile like a vehicle.

I know this has been a long article, but the needed change here is really very simple. You should be allowed to remove the chassis from a factory-built house, and then having done so, every other aspect of the law — zoning, mortgages, etc. — should draw no distinction between a house built in a factory and placed on a foundation and a house built on-site.

Up from the trailer park

This is inherently speculative, but I think there is reason to believe that there is significant room for low-end disruption of the housing market achieved by eliminating regulatory discrimination against manufactured homes.

For starters, we know that a non-trivial share of the population is being poorly served by the existing market. There is a lot of homelessness in the United States, and we also have about 6% of the population living in housing that’s considered overcrowded. A healthy chunk of this, obviously, is accounted for by urban land use issues that won’t be fixed by small manufactured homes. But every little bit helps, and plenty of land in American cities is occupied by single-family homes.

But the current rules not only impair the supply of manufactured homes — they specifically prevent the move further up the market that is the essence of low-end disruption.

After all, part of what happens when you zone factory-built homes out of desirable neighborhoods is that you basically guarantee that affluent people won’t buy them, so the upside to making higher-quality and more expensive units is limited. But absent regulatory constraints, a factory-built house wouldn’t necessarily need to be a “cheap” option, per se — just a better all-around value proposition than a stick-built house.

The other thing is that factory-built houses benefit from increasing returns to scale. When factories are running at capacity, unit costs are lower. When demand is sufficient to open more factories, shipping costs fall. So you can have a flywheel of falling costs and higher quality.

Does this ever get you to the universe where modular panels are disrupting custom homebuilding?

I do think Vernon’s skepticism here may be warranted. The big issue is that once you get into higher price points, you are really dealing with the vagaries of taste and fashion. Affluent people seem to be happy to pay a lot of money for extensive customizability, while generating productivity gains via modularity depends on standardization. On the other hand, fashions can change. Right now it’s very normal for an affluent family to buy a custom home and fill it with furniture from chain stores. Thanks to pandemic-induced supply chain issues, I wound up buying a custom desk from a local craftsman this past year. If you go that route, you pay a price premium, but you also get something nice. Maybe in the future, we’ll see more modularity in homes and more customization in furniture.

Limited gains could be very valuable

This also fundamentally ties back into other aspects of land use. An open question that we debate in YIMBY circles is what happens to land prices in YIMBYtopia when we’re allowed to build anything anywhere. On one level, deregulation should increase land value. On another level, reduced scarcity should make land more affordable. The boring, sensible answer is “it varies from place to place.” But one possible situation is that in a new, more affordable, more density-friendly world, people of means who prefer low-density living end up getting much larger houses or more of a reversion to sprawling estates with out-buildings.

Anything like that sort of changes what competition is all about in construction. That being said, even if the gains end up being limited to the low end of the market that’s still a very big deal.

We have homeless people in America. We have people living in overcrowded housing. We have people trapped in neighborhoods with high crime and bad schools. Housing is both a key to human dignity and also a key to all kinds of access to economic opportunity. We also just have a lot of people who, if they could spend less on housing, would have more to spend on other things. That spending could power the economy forward in other ways.

Anti-modular NIMBYism has some relationship to anti-density NIMBYism, but they are fundamentally different in other ways. Opposition to factory-built housing is really not about impact on neighbors at all — it’s protectionism. These moves were driven by the National Association of Homebuilders because homebuilders like making money.

Part of the joy of a full-employment economy is that we can say no to protectionism. We don’t need to “create jobs” in the current economic climate; we need to produce the goods and services that people need more cheaply and more effectively. Legalizing trailers is one huge way to do that.

Regulatory capture across the country is a huge impediment to improving people's lives. Matt highlights one area in this post (essay?, blog?, I never know how to describe a substack writing), but it extends into almost every part of our lives. Licensing rules for everything from hairdressers to car dealerships to real estate brokers inhibit competition and act as a hidden tax on consumers while protecting entrenched interests.

President Biden's recent executive orders are a good step, but they are limited in scope. The battle against these silly regulations - is it really necessary to require 2,000 hours of training to be a barber? - happens primarily at the state level. This should be an area where conservatives and progressives come together - more competition, enabling a pathway for lower-income people to improve their lives and a shrinking the regulatory state. Entrenched interests, though, have captured so many of the licensing bodies, it will take dedicated people working the details. I'd love to know how to find and support anyone who is working in this area.

I write the newsletter Construction Physics, which is what Austin based most of his post on, and have written about this issue a lot.

First, a bit of a clarification. Manufactured homes are homes that don't meet local building codes, but instead meet the HUD code for manufactured homes (which, among other things, requires the permanent chassis). But there's nothing stopping anyone from building a home in a factory that meets local building codes, and putting it up on a normal site just like a normal house. The reason this isn't more popular is that it tends to be more expensive than traditional construction.

The main issue preventing returns to scale in home construction is shipping and logistics. Homes are so big that to prefabricate them you have to either break them into panels (adding a lot of upfront complexity and still having significant site work) or ship them as large modules that require carefully planned routes, follow cars, large cranes to set, etc. The result is that you tend to see prefabricated homes (and other buildings) shipped relatively short distances, generally less than 500 miles. This fundamentally limits how big a market you can serve and what sort of scale you can achieve.

Even manufactured homes don't really get around this. Clayton has something like 17 factories around the country to deliver a relatively small number of homes (in the neighborhood of 50,000).

Many, many companies have tried and failed to overcome this, Katerra (a 2B-dollar prefab construction startup that just went bankrupt) being the latest.

Also, I think Matt is overstating the importance of high land cost. The vast majority of population growth (and thus new construction) occurs in the south and the southwest, places where the land cost is very low and the cost of a new house often approaches the cost of construction. You actually see a fairly strong correlation between cost of construction and population growth, but NOT any correlation between home cost with the price of land and population growth. So lowering the cost of construction would have fairly enormous effects if you could figure out how to do it.

For manufactured homes, I think the larger issue than zoning is the way they're financed. These are almost never financed as real estate, but as personal property. So the loans for them have higher interest rates, and they don't maintain their value over time the way a traditional home does. But there's a new type of manufactured home called a "CrossMod" that's advertised as built like a manufactured home but financed like a traditional home - we'll see how that does.