To build an egalitarian society you need taxes

It's difficult, but there's no shortcuts

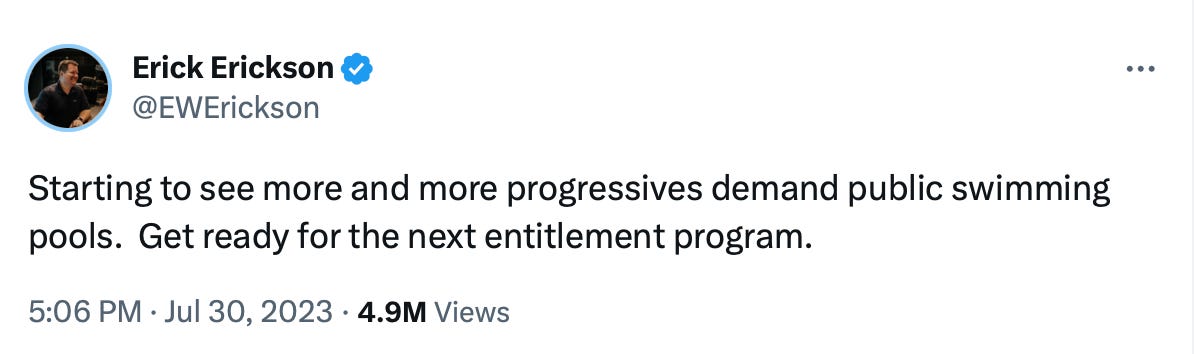

I was thinking more about elite college admissions and why I find that discourse frustrating when I saw this Erick Erickson tweet about the evils of public swimming pools.

I’m puzzled by the suggestion that this is some new thing. I’ve really only ever lived in New York City and Washington, D.C., and both places have public pools and have had them for my whole life. I like the D.C. pool system a lot; it’s a good way to cool down in the summer, and there was also a time when I was going to an indoor pool almost every winter Saturday with my kid to pass the time. We’re not as frequent users of those indoor pools as we used to be, but we still enjoy them on occasion.

More broadly, though, the existence of public recreational facilities is surely something Erickson is aware of. Every town I’ve ever been to has public parks and playgrounds. America has lots of public beaches. During Covid, I frequently drove out to various nature preserves and state parks and battlefields in the suburbs to go on kid-friendly hikes. Now that indoor living is back, I’m not out hiking that much. But we still do it sometimes with friends. Who doesn’t like having public recreational facilities?

What does this have to do with college admissions? Well, because I think it’s such a natural and correct vision of what an egalitarian society looks like. The point of the city pools isn’t that access to the pool is “fair” — like they are genuinely choosing the best swimmers on merit rather than relying on privilege or insider connections — the point is that the pool is open to everyone. If you want to go down to the Barry Farm pool and use an indoor waterslide on a winter’s day, you just go. If you want to have a picnic in the park, you just go. If you want to grab a book from the library, you just go.

The downside of all of this is that providing public services costs money. Things that cost money need to be paid for with taxes, and people generally don’t like to pay taxes. So that’s the push and pull — quality services (yay!) versus high taxes (boo!) — which is part of what politics is about. But this is the debate. In an egalitarian society you have relatively high taxes and lots of services and benefits, so the gaps between those with the highest and lowest material living standards are relatively modest. That’s the name of the game, not the procedural fairness by which people come to obtain relative positions in the social hierarchy.

The arbitrariness of merit

A tick of the modern age is that if you’re successful, you’re supposed to demonstrate humility by talking about various forms of identity-based privilege you’ve benefitted from in life. And those are, sure enough, real things.

But I think those privileges barely scratch the surface. The fact of the matter is that whatever privileges I may have benefitted from in life, a big part of the reason I’m successful is that I am, in fact, much better than the average person at writing high volumes of cogent articles. But this is a bit of a time-bound and arbitrary talent. I’ve worked alongside a lot of people who are better than I am at taking 2–3 weeks to write a single long-form article. I’m more successful than most of those people, because it happens to be the case that at our particular point in history, taking 2–3 weeks to write a single long-form article is a less valuable skill than writing 4–5 columns per week. But 25 years ago it was exactly the opposite; in the print age, column inches were scarce and the winning strategy was to be someone who, given enough time and effort, could generate something really, really good. In the digital age, space is plentiful and the winning strategy is to fill the space with content that’s pretty interesting or informative or entertaining.

These are related skills — the people who are really good at one are usually at least above average at the other — but they are distinct. And it’s not just a question of practice. I have tried over the years to do feature writing, and I just don’t reach the heights that many other people in the field are capable of.

I’m fortunate not only to be alive at a time when the kind of content production I’m good at is valuable but to have come along in the industry right when things were turning. I graduated from college in 2003, and for the first four or five years of my career, digital work was still considered low status. That meant it was relatively easy to get my foot in the door, and I was already a well-established voice when the 2008 financial crisis blew up print journalism in a way it’s never recovered from. That’s tremendous good luck in life. But it’s not luck as opposed to merit, it’s that questions of what skills happen to be valuable and who has them and at what time are all highly contingent. And these market judgments about what skills are valuable not only shift over time, they aren’t ethical judgments about people’s worth.

Lionel Messi is fortunate to be a great soccer player and even more fortunate to be at the peak of his fame at a moment when an influx of U.S. and Saudi money is making soccer skills more valuable. But he’s not a better, more meritorious person than a really good elementary school teacher who also coaches a youth soccer team. Teaching just doesn’t scale in the same way that being a star entertainer does, so it doesn’t pay off in the same way. It’s good on a lot of levels to mostly let people buy and sell things at prices they want, but that’s a means to generate an efficient allocation of resources, not a moral judgment.

Egalitarian countries tax and spend

What should we do about this? Well, if you look at countries that have a more egalitarian distribution of material resources than the United States, what you generally find is a larger system of taxes and transfers.

And I would say that this kind of look at disposable household income probably understates the extent of implicit redistribution because it slights the value of in-kind public services. John Kenneth Galbraith wrote decades ago about “private affluence and public squalor” in the United States, and the gap has probably grown larger since then.

Some people seem to regard this as a kind of cheating.

James Heckman, who’s a major advocate for early childhood education programs, complains that Denmark has a fairly high level of social stratification despite its generous welfare state. Their preschools, in other words, aren’t good enough to somehow undo the fact that kids from the top decile are much more likely to end up in the top decile than are kids from the bottom decile.

But this seems to me like missing the point. In Denmark, the actual gap in living standards between the bottom and top deciles is much smaller. You can’t do anything about the fact that some people are better at certain things than other people or that some skills are more lucrative than other skills. But you can absolutely do something about the consequences of being on the bottom. In the United States, these consequences are severe relative to a world in which we have a universal child allowance, guaranteed health insurance, safer streets, and better public transit. But the consequences are much less severe compared to what they would be if we implement House Republicans’ plan to take away poor kids’ nutrition assistance or close all the public pools. This stuff isn’t a distraction from questions about preschool quality and college admissions — the actual standard of living people end up with is the most important thing.

The goal is broad-based prosperity

Of course, your city can’t build pools and hire lifeguards unless it has a dynamic, growing economy. Nobody wants to live in a highly egalitarian society that’s equal because everybody is poor.

It’s easy to underrate how much growth matters to this kind of thing. But take Social Security. Due to population aging, we’re going to need some mix of tax increases and benefit cuts to avoid exhaustion of the Social Security Trust Fund in the relatively near future. Those are unpalatable choices. But if productivity growth had continued on its 1996–2005 trajectory for the past 15+ years, the need for changes would be much smaller and further off in the future.

Back when Lyndon Johnson enacted the Great Society, the American economy was in the middle of a period of very robust growth. That made it much easier, both politically and economically, to invest in social services than it is under contemporary circumstances.

At the same time, an expansive welfare state should make it easier to maintain pro-growth policies. Everyone craves a certain amount of security in life, but a dynamic economy involves ups and downs. When I was born, my mother was a very expert analog graphic designer who had lots of X-Acto knives, T-squares, rubber cement, and little strips of typographic lead. Computers killed off that mode of graphic design and devalued those skills. Work related to media is unusually prone to technological disruption because the First Amendment largely precludes people in our fields from creating huge regulatory barriers to entry. But lots of Americans currently have their nominal earnings propped up by occupational licensing rules or other weird franchises like the laws that protect car dealership owners and liquor distributors. Homeowners tend to favor NIMBY structures that make everyone (including most homeowners) poorer on average but that mitigate downside risk.

It’s better in all these cases to genuinely go for growth and have a general social guarantee that the fruits of prosperity will be spread through taxes and public services.

Having fair opportunities is, of course, part of that. Society suffers when talented people are locked out of the chance to make major contributions due to their race, gender, or other circumstances in life. And this is as much an issue for growth as for equality — if Katalin Karikó hadn’t been able to become a scientist and develop mRNA technology, we’d all be much worse off. But opening up opportunities for the most talented members of disadvantaged groups doesn’t change the fact that some people are bound to end up at the bottom of any social hierarchy. And the big question of justice and equality is ultimately how are those people faring, which is going to come down to society’s overall level of prosperity and its ability and willingness to share the benefits of growth with everyone.

That stuff is kind of a hard lift politically and can be sort of a bummer to think about, so I understand the desire to find “one weird trick” solutions to social inclusion and economic equality. But it’s important to face reality in a more clear-eyed way.

I tend to be in favor of free trade, skeptical of unions (particular public service unions), opposed to excessive regulations, and a number of other positions that would likely be seen as right of center or at least centrist.

But it's generally because I believe that taxing winners and using that revenue to fund a high level of public services for all is a better way to achieve social goals. I would significantly increase the current level of taxes in the U.S. and use those resources to make our public services and safety net better.

It’s true that earnings are not based on merit. But they are based on generating value for other people. And that seems pretty fair to me.

The utilitarian case for higher taxes is very strong. But the justice case is pretty weak - largely rich people do deserve their money.