The two-state solution is still best

In defense of a cringe idea

Saying you support a two-state solution to the Israel/Palestine conflict is the most cringe position imaginable.

If you want to participate in pro-Israel politics you’re supposed to say that Israel has repeatedly offered this only to have it rejected so there’s nothing more to talk about and certainly no case for pressure. Besides, everybody knows that anti-Israel politics is just antisemitism so it doesn’t matter what the Israeli government says or does about anything. And if you want to participate in contemporary pro-Palestinian politics, you’re supposed to agree with Yousef Mounayyer that the two-state solution is dead and agree with Ben Burgis that “from the river to the sea” is nothing more than “a call for democracy and equality.”

Meanwhile, Mansour Abbas, who heads the most important political party for Palestinian citizens of Israel, supports a two-state solution.

The governments of Egypt and Jordan and of America’s allies in the Persian Gulf support a two-state solution. A two-state solution is endorsed by the Palestinian Authority in Ramallah. It’s also endorsed by Marwan Barghouti, the most popular Palestinian political leader, who is currently sitting in an Israeli prison for his role in orchestrating the Second Intifada. It’s backed by United Nations resolutions. In theory, it’s backed by Joe Biden, though as his critics will point out, there’s no teeth to that position since in practice US support for Israel is not conditioned on anything relevant. But a key reason that Biden’s two-statism is so hollow is that when Barack Obama tried to exert meaningful pressure toward two states, he was undercut in Congress. A lot of pro-Israel politicians in both parties are at least nominally in favor of such a solution, but they are more in favor of being pro-Israel than of any particular outcome so they don’t favor pressure — particularly in a context where the Israeli government has clearly turned the page on this.

But that still leaves us with the question of Palestine.

I think that if you’re a young person who’s on the left because you think climate change is real and abortion rights are important and health care should be a right rather than a privilege, you almost certainly also think that it’s awful to see so many Palestinian civilians dying in Gaza. You probably “sympathize more” (as the pollsters say) with the Palestinians because they are suffering more. And you would like to be pro-Palestinian. If you look around at what your peers are posting, it’s clear that the pro-Palestinian thing you are supposed to say is that Israel is settler-colonialism, similar to Apartheid South Africa, and that system should be destroyed. Realistically, 99.9 percent of people aren’t going to put any more thought into it than “I want to signal solidarity with Palestinian suffering so I’m gonna repost these slogans.”

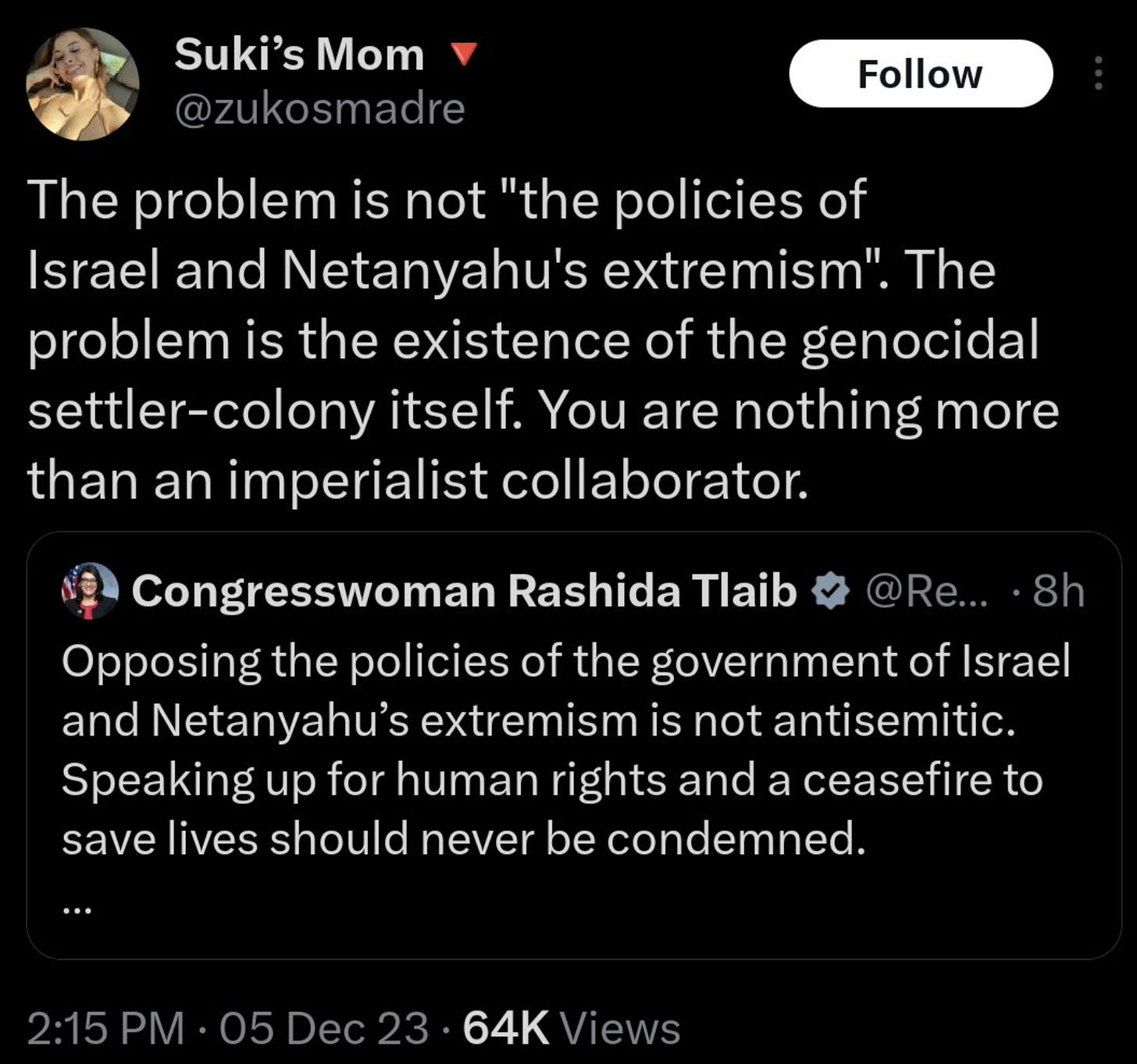

If someone shows up and says “look, guys, if we tell Israel that we want ‘free Palestine from the River to the Sea,’ occupation and war will continue indefinitely, whereas if we tell Israel that we want an independent Palestinian state, we might be able to get it,” that person is going to get yelled at. Idiots on the internet are happy to yell at Rashida Tlaib for insufficient anti-Israel posturing, so no normal person is going to stand up for the view that moderation of Palestinian demands is the best way to achieve a better life.

But there’s still the matter of Abbas (and the other Abbas) and the Arab League and the UN and most of the other people close to the situation.

So it’s worth saying that the cringe position here is the correct one. The most plausible path, by far, to a better life for Palestinian people and to a more peaceful region is the creation of two independent states for two people.

The myth of Israeli generosity

A perennial issue for countries attempting external-facing propaganda is that the internal audience also sees it, and the content of the external message is influenced by internal concerns. And I think that Israeli messaging on the conflict (Hasbara) has so influenced Israeli domestic opinion that a lot of Israelis have become genuinely confused about what’s been going on.

Here are some true things:

In 1948, when Jews represented about a quarter of the population of Mandate Palestine and Arabs wanted to halt Jewish immigration, an offer was made to give Jews half the land for a Jewish State that could then host more Jewish immigrants. Arabs rejected that as a bad deal, so a war was fought, and the Jews ended up with a larger state than they were offered in partition.

When Arab states controlled the Gaza Strip and the West Bank from 1948-1967, they could have created Palestinian states (though not a unified Palestinian state because that would have required Israeli cooperation) on those territories. But they did not. Instead, Jordan annexed the West Bank, and then later Egypt and Syria and Jordan attacked Israel.

The Palestinian predicament really is substantially a result of poor decision-making on the Arab side of the conflict.

But Israelis seem to have convinced themselves that their governments spent the entire Oslo period making generous offers of statehood to the Palestinian Authority, only to be brushed away. What actually happened is that the Peres and Rabin governments never held final status talks, then Israel elected a prime minister who opposed the whole idea of a Palestinian state. In 2000/2001 and again in 2008, Palestinian leaders were summoned by the United States to attend summits with lame duck Israeli leaders who were sinking in the polls and on the verge of losing power.

At Camp David, Yasser Arafat blundered and did not offer a real counterproposal to Ehud Barak. But in 2008, Abu Mazen did make a real counterproposal — one that would have involved evacuating more settlements than Israel wanted to evacuate and in exchange would have improved transportation logistics between Palestinian towns. But his negotiations with Ehud Olmert didn’t matter because Olmert resigned the next day. Olmert’s coalition partner, Shas, rejected Olmert’s offer as too generous. Olmert’s successor as the head of the Kadima Party, Tzipi Livni, ran on a platform of continuing negotiations in the spirit of those talks and she lost. That was in 2009, and since then, nobody has come close to obtaining a Knesset majority for the kind of policies that Olmert put on the table in Annapolis.

This is not to say that peace would have been achieved had Livni won. The Olmert proposal was different from the Abbas proposal, and it’s not clear Abbas could have sold his proposal domestically either. But here’s my point: Imagine a world in which Livni won and stuck to Olmert’s proposals and didn’t allow settlements outside Olmert’s proposed borders. Even if that didn’t lead to peace, it would be a factually different situation in which one could truthfully say that the cause of ongoing occupation was Palestinian unwillingness to say yes. But that’s not the world we are in. Israeli politics has only very fitfully flirted with the two-state solution and mostly rejected it.

Not because Israelis are all fanatics (though many of them are), but because crucial swathes of Israeli opinion are genuinely fearful of the security implications of a two-state solution.

A two-state solution has become safer

Israel is very small. When AIPAC organizes tours of the country, they famously take people on a helicopter ride to visually illustrate the size of the country, and upon return to America, you’re supposed to recount that anecdote to demonstrate that you’re pro-Israel. They wouldn’t send me on one of their trips for journalists (but it’s been a while since I asked, and I still like free trips!) so I have not personally experienced this, but it really is a small country. The idea that the West Bank could be used as a base for deadly attacks not only on Jerusalem but on Tel Aviv and Haifa isn’t crazy.

But since Oslo, the Israeli relationship with Jordan has gotten much better.

The country’s relationships with the UAE, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait are also vastly improved. It has a very strong working relationship with the government of Egypt. Syria, meanwhile, has completely collapsed as a state capable of credibly threatening anyone. At this point, not only do these countries sincerely have no interest in attacking Israel, they clearly want to ally with Israel against Iran. The sticking point is the Palestinian issue. It’s a really “bad look” for the Sunni states to be seen as aligning with Israel against Iran while Iran backs the Palestinian cause.

Under those circumstances, a Republic of Palestine is not a military threat to Israel, it’s a critical partner in sealing a partnership between Israel and other friendly states in the region.

This is important because while the haggling over the exact boundaries obviously matters, there’s also the basic question of whether Israel should pursue a two-state solution. The Israeli answer has mostly been “no,” with prime ministers only sporadically going for it on their political deathbeds and in the face of intra-coalition dissension.

I think this is based on an outdated assessment of the security situation and also on a misreading of Palestinian reluctance. Pro-Israel political culture is soaked with paranoia about a “two-phase” Palestinian plan in which first, you get a Palestinian state and then you try to seize the rest of the land from the Jews. There is some evidence for this in polling of the Palestinian population, and of course demands for a “right of return” for generations of descendants of people who fled the 1948 war in some sense amount to such a plan.

But Israelis should take more seriously the fact that Arafat rejected Barak’s insulting first offer at Camp David and his better second offer at Taba. And they should take even more seriously that when Abbas received Olmert’s offer at Annapolis, he replied with a counter-offer that featured a bunch of small differences regarding the precise border. There was no secret plan to make a deal and then welch on it — Palestinian leaders know that would be catastrophic in terms of both domestic and international politics and are, in fact, trying to negotiate a good deal for themselves.

A good deal is still possible

Of course, Israelis will say that Palestinians don’t want a good deal for themselves, they want to push the Jews out.

Of course, there are millions of Palestinians and some of them do want that. Even more, the Palestinians are embedded in a larger Arab World that contains hundreds of millions of people, the vast majority of whom have no concrete stake in obtaining Palestinian statehood, but who do nurse various anti-Zionist grudges. From a pure discourse standpoint, a good way of bridging the gap between Palestinians’ concrete interest in securing national sovereignty and the sizable audience for ideological anti-Zionism is to claim that a two-state solution is now impossible. This is normally argued with reference to Israel’s habit of building far-flung settlements in the Jordan River Valley and along the mountain ridge that runs through the center of the West Bank.

But endless repetition does not make this true. Here, courtesy of the Israel Policy Forum, is a map developed by Shaul Arieli in which 77 percent of settlers are absorbed into Israel via small annexations, and the Republic of Palestine is fully compensated with land swaps.

Resettling 150,000 Jews into Israel proper is not a totally trivial undertaking, but about a million Soviet Jews made aliyah in the 1990s, so it’s hardly unprecedented.

There’s a slightly odd horseshoe between Israeli fanatics and doctrinaire Marxists trying to convince the world that Israel has some kind of material stake in maintaining these settlements. The truth, though, is that it’s not 1923, and controlling agricultural land is not an important part of the Israeli economy. Israel does face significant housing cost issues that help push people into the settlements (which are subsidized by the government), but this is a banal urban planning and housing policy issue. Israel is a densely populated country (comparable to Belgium or the Netherlands and denser than Japan) that doesn’t have a big, dense transit-oriented city with a proper metro system. But that’s a question of national priorities. Israel has chosen to invest resources in establishing far-flung settlements in order to control the West Bank rather than in mass transit in Tel Aviv which would be a much more workable solution.

Separate from the logistics, Israeli leaders would be reluctant to either forcibly resettle its citizens or to abandon them in a new State of Palestine. If Israel didn’t care about minimizing settler relocations, they could have accepted proposals that PA negotiators made in 2001 and 2008 that would have maximized West Bank contiguity at the cost of significant evacuations.

But in terms of convincing Israel to make changes that it is reluctant to make, there is no way that “evacuate 150,000 people and move them a few miles west” becomes a tougher ask than “abolish the fundamental identity of your country.”

And that remains true whether you are talking about a persuasion campaign, revolutionary violence, diplomatic pressure from the United States, or a massive sanctions effort.

It matters what Palestinians ask for

I think that western critics of Israel have done Palestinians a real disservice by indulging sloppy Overton Window thinking in which putting binationalism on the table increases pressure on Israel to cut a deal to avoid it.

The exact opposite is the case — putting binationalism on the table makes Palestinians look unreasonable and extreme and increases western reluctance to put pressure on Israel. In part, because of the colonialist and racial overtones that draw the attention of western intellectuals, the West is going to side with Israel in a zero-sum conflict between Palestine and Israel, a basically functional liberal democracy that serves as a recognizable kindred spirit. Of course, what distinguishes Israel from other liberal democracies is that it’s ruling over occupied territory, denying citizenship to most of that territory’s residents, and planting settlements on it.

If you want to get people to pressure them to stop that, you need to be calculated and precise — you want them to stop that specific thing as an end goal. When you refer to urban warfare as “genocide,” chant about liberation “from the river to the sea,” and complain a lot about stuff that happened 70+ years ago, that makes most people feel that Israel should get a pass on all of it.

I would also note in this regard that people who angrily protest that decolonization means binational democracy seem to put exactly zero effort into trying to figure out the logistical details of how this is supposed to work.

Many of these arguments hinge on the supposed impracticalities of a two-state solution, but there’s no shortage of maps that have been drawn over the years that precisely delineate hypothetical borders and land swaps while one-staters have … nothing. What kind of electoral system will be implemented? How will the constitution work? How are you going to deal with armed non-state actors? To be generous, it’s a utopian program being pushed by people who aren’t very thoughtful. To be less generous, it’s a blueprint for war and killing. Realistically, the whole thing is being driven by oddball campus norms in which you’re never supposed to critique the actions of the people fighting oppression, so the most extreme slogans inevitably win out.

The truth, though, is that Palestinians are in a vulnerable position. They deserve better than their current lot in life. To get something better, they are going to need to recruit third parties to put pressure on Israel. And to do that, they need to formulate a defensible political agenda — a halt to settlement expansion, negotiations over a deal featuring a mix of evacuations and land swaps — that appeals to fair-minded people. This is exactly what Arab actors with actual skin in the game — the PA in Ramallah, Ra’am in Israel, the leaders in Cairo and Riyadh, etc. — have been saying, but they are continually undercut by posturing radicalism that prolongs the conflict.

Great post! I've learned a lot from this and your other posts on the conflict. But I think "actually, the real problem is housing and transit policy in Tel Aviv" deserves some sort of award for Most Yglesian Take of 2023 :-)

Some thoughts.

1. We largely don't really know what Palestinians' demands for an acceptable state are. If you listen to Tareq Baconi's recent appearance on Ezra Klein's podcast, for instance, he claims that the right of return is *an absolute minimum* demand for Palestinians. He seems to believe Hamas was in the right to scuttle the peace process, since the right of return was never on the table. Ezra seems shocked at how crazy all of this sounds.

By all appearances, though, Palestinians seem to be willing to endure extreme suffering in order to avoid accepting anything that is less than their minimum acceptable state. So it's important to actually figure out what those demands are, and no one has ever articulated them.

EDIT: Some commenters have noted that I misunderstood Baconi (keeping the original just so others can see what I had written before being corrected). What he's saying, apparently, is that Israel needs to *acknowledge* a right to return. But still, I'd like to know exactly what is considered an acceptable offer of a state.

2. It's telling that we have this assumption that a two-state solution requires some plan to evacuate the Jews from the West Bank. On the other hand, we never talk about a two-state solution requiring a symmetric plan to evacuate Arabs from Israel. Even the staunchest leftists operate under this assumption without realizing how damning it is.

Why do we make this assumption? Everyone knows why.

3. I also find it odd that discourse always talks about this issue as though the more powerful party needs to be the one to make concessions. So, for example, Barak's offer of a state is considered "insulting" because it didn't include exactly 100% of the West Bank, and there was no mention of the patently insane "right of return." Shouldn't Israel be willing to give Palestinians a little more, given that they hold all the cards?

This logic is really never applied anywhere else, for obvious reasons. In conflicts, losers make concessions, not winners! Has a country ever lost this many *offensive* wars against an opponent and then felt entitled to make demands?