The stationary bandits of New York City

Urban governance needs reform, not whatever the Cuomo/Mamdani debate is

For most of recorded human history, government has been fundamentally predatory. Prehistoric hunter-gatherer bands could maintain decent material conditions with some luck, but the lifestyle didn’t really lend itself to stockpiling wealth. As a result, social structure was necessarily somewhat egalitarian and there wasn’t that much to steal.

Things changed with agriculture.

A settled farming community can produce more food than it needs to survive, which means that raiders can profitably steal it. But as Mancur Olson pointed out in his later work, as profitable as banditry may be, a skilled group of warriors might decide that it’s even more profitable to act as “stationary bandits.”

Instead of sporadically raiding farming communities, stationary bandits live nearby and tax them — they are, in other words, the government. James Scott argues in his book Against The Grain for the specific significance of the interplay between banditry, state-formation, and the cultivation of grains like wheat, barley, and rice. Unlike tubers, these crops are easily visible on the surface. They have to be harvested at specific times of year, so it’s easy to know when to tax or steal them. And unlike fruits and vegetables, they can be dried and stored for a long time, which allows for the accumulation of large stores of wealth.

Stationary bandit theory is cynical about government, but not entirely negative.

One of Olson’s points is that stationary bandits, unlike roving ones, have some genuine interest in encouraging the communities they govern to prosper. They need to protect their victims from other bands of bandits. If they provide things like law and order, basic infrastructure, and other growth-oriented public services, then there’s more tax revenue to secure. Stationary bandits want to cultivate the growth of artisan classes and skilled craftspeople who can make stuff for them. They want to protect trade routes and facilitate commerce. It is much better to live in a community where you need to fork over taxes once a year or else armed men will kill you than to live in a community where armed men stroll through periodically, killing and stealing at random. And this is validated even in the modern day. A very good new paper from Raúl Sánchez de la Sierra shows that in the somewhat anarchic circumstances of the contemporary DRC, communities are better off when they’re ruled by predatory militias than when things are just in a state of chaos.

Still, these are predatory regimes. There’s a delta between “tax revenue received” and “useful services provided,” a delta reflected in the lavish palaces and luxury lifestyles of the rulers.

The projects of democracy and liberal rights aim to change that and refocus government spending away from things like building huge pyramids and toward taking care of the sick, elderly, and disabled. But it’s important to recognize that the whole idea of government as even aspirationally serving the public interest is relatively new compared to the history of the state. And it’s deeply imperfectly executed, especially in circumstances where voters aren’t closely monitoring the elected officials and over geographies that have strong underlying economic fundamentals.

Which is part of the reason why governance in rich American cities often seems so bad: The agglomeration externalities create a lot of surplus for the rulers to appropriate and most residents don’t pay close attention to politics, so extractive political coalitions run cities for their own benefit.

Governance for the governors

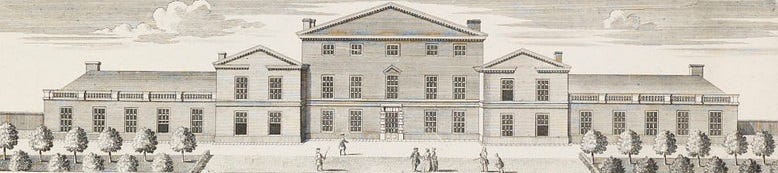

This is a picture of what was the main building in the Kew Palace complex circa 1734, when it was the residence of Frederick, Prince of Wales.

At this time, the sustained spurt of productivity growth associated with economic modernization had been under way in England for about 130 years. But real wages were not growing for the average English person and in fact were significantly lower than they had been in the 15th century.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.