The power of a single-issue group

Narrow interests can get things done and reduce polarization

Chris Elmendorf and David Schleicher wrote a piece for Niskanen’s Hypertext magazine arguing that it’s time for YIMBYism to transcend its single-issue orientation and become something more like a moderate “urban growth and reform coalition,” linking housing reform with issues like public safety and education quality. I like this idea a lot; I think the Grow SF organization and Daniel Lurie’s wildly popular new mayoralty in San Francisco offer proof of concept. In my real life, I’ve had some meetings and conversations to try to build bridges between YIMBYs in DC and the local business interests and charter school advocates who anchor “moderate” factional politics.

This strikes me as a particularly under-funded brand of politics, because it’s essentially the politics of rich people who live in cities.

Faced with a wave of support for Zohran Mamdani, rich New Yorkers mostly seem to be whining ineffectually while circling the wagons around the city’s stationary bandits. Instead, wealthy moderate New Yorkers should fund real para-party institutions. Those institutions should pair critiques of democratic socialism and defense of the business community with an actual agenda for urban reform, an agenda that would take on housing challenges but also the hapless MTA and other aspects of the dysfunctional status quo. And I’ll be less subtle here than the Niskanen publication itself: Donors should give money to multi-issue think tanks like Niskanen so they have the resources to work on the full suite of urban issues.

That said, without disagreeing with anything Elmendorf and Schleicher say in favor of this option, I do want to pitch it as both/and rather than either/or.

I think that the strength of YIMBYism over the past 10-15 years has largely derived from its single-issue orientation during a time of relentless political polarization.

Plenty of influential YIMBY leaders have what I think are toxic, quasi-fascistic views on social and cultural issues. Some YIMBYs support the dramatic expansion of the welfare state, and others support Trump’s egregious OBBBA legislation. There are YIMBYs who hate charter schools and YIMBYs who favor unregulated school choice. And while I absolutely do want to build multi-issue organizations that push a coherent vision of reform urbanism, I want to acknowledge that, not only are there YIMBY leftists, there are also legislators who vote for good housing bills who would never in a million years identify as an “urbanist” of any kind.

It’s good for housing policy to have organizations that monolithically focus on housing. But I also think it would be good for America to have a resurgence of single-issue groups that are not closely aligned with larger coalitions.

The grand coalitions

A funny thing about American politics is that in the early 1980s, when the secular increase in partisan polarization was just beginning, the conventional wisdom was that parties were going the way of the dodo. Journalists, political scientists, and politicians themselves conceived of political parties almost, by definition, as only lightly ideological machine-type organizations that were obsessively focused on winning.

This was in part a reaction to the rise of highly ideological issue organizations in the 1970s. NARAL and the NRA didn’t really care about winning elections in order to control patronage — they cared about abortion rights and gun rights. They would happily sink an effective politician in a primary if he wasn’t supportive of their key issue. And they would endorse across party lines. Democrats, early on, were more influenced by the feminist movement and more open to feminist input on a range of topics, including abortion rights. But when the issue was fresh on the political scene, there were plenty of pro-life Catholic Democrats and plenty of pro-choice Republican WASPs. The environmental movement fought battles with business interests, but they fought battles with labor unions too.

These groups seemed to be dissolving the traditional fabric of American political parties, turning the labels into somewhat meaningless vessels as entrepreneurial politicians assembled both electoral and legislative coalitions on the fly.

But, of course, that’s not what happened.

The Reagan administration transformed the Republican Party into a semi-coherent vehicle for a semi-coherent conservative movement that worked across issue areas to pair gun rights and anti-abortion politics with the idea of siding with business against labor and environmentalists. It gave up on the GOP’s historic links to African-Americans and re-conceptualized the civil rights movement as just another push for government regulation. Because the rise of the conservative movement was so successful, it’s pretty well known and a lot of books have been written about it. The story of the parallel effort to create a successful coherent progressive movement is not as well-known, but as my friend Sam Rosenfeld details in his book “The Polarizers,” there was also a lot of deliberate work here too. Left-wing intellectuals, organizers, and funders spent years building bridges between labor, environmental, feminist, and civil rights organizations.

Out of this emerged a broad church, multi-issue progressive movement.

I met Heather Booth in 2010 when she was running an advocacy group called Americans for Financial Reform, which was pushing for tougher Dodd-Frank provisions and a strong Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. It was only later that I learned she’d been involved in CORE and SNCC in the 1960s and the Jane Collective in the 1970s and coal strikes in the 1980s. She’s both emblematic of the emergence of coherent multi-issue progressivism, and also one of the leaders who literally did the work. In part, the work was stitching together these large constituency pillars. But it was also identifying gaps in the ecosystem and making the argument that even if there wasn’t a large organized constituency around financial reform, it’s a hot topic in politics and there should be a distinct progressive movement position on it.

This progressive movement has historically been less influential over the Democratic Party than the conservative movement has been over the GOP. But that’s changing. The Biden administration, unlike its predecessors, relied heavily on progressive institutions to guide its staffing. And Democrats now raise the vast majority of their money from ideological progressive donors rather than transactional interests. Having dissolved partisanship in the 1970s, the new ideological movements now anchor polarized political parties in a way that’s much more rigid than ever before.

The decline of the single-issue group

One result of this is that the two parties have become more ideological. But another is that issue advocacy groups have become less focused on their actual issues and more focused on the omni-cause.

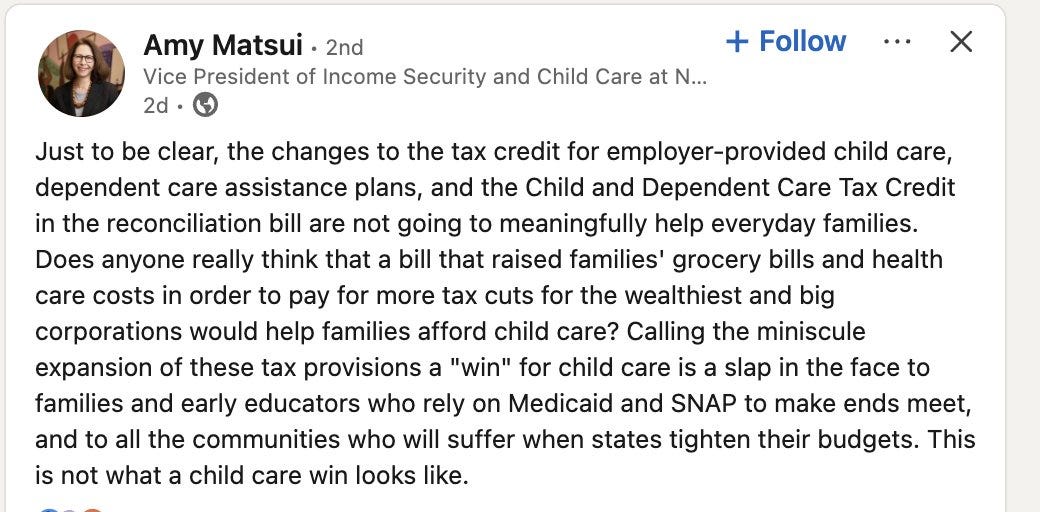

Sometimes this is downright comical. I heard a story about an abortion rights group canceling a canvassing campaign in support of a Democratic challenger in the 2024 cycle because they didn’t like a position she’d taken on border security. But often it’s more subtle. For example, Rachel Cohen wrote a good story about how there’s $16 billion in day care funding tucked away in OBBBA, which her article characterized as “a child care win.” Amy Matsui, who does child care policy at the National Women’s Law Center, blasted Cohen on the grounds that OBBBA is a bad law.

And she’s right — it is a bad law, as I’ve said many times. But it’s rare to write a multi-trillion dollar piece of legislation with dozens and dozens of provisions and not come up with at least one good one. There’s a child care win in this law. More and more organizations, though, find themselves subordinated to the larger logic of the coalition. Perhaps the most infamous example of this is the ACLU, which saw an influx of money during Trump’s first term and expanded to take on a wider range of causes, but also semi-abandoned its traditional role as a content-neutral defender of free speech.

This was a real loss for the ecosystem.

Participating in ideological coalitional politics is a perfectly legitimate thing to do. But defending free speech is also an important cause; it’s just inherently a cause that is never going to fit comfortably into a partisan or ideological coalition. A reasonable person can appreciate both kinds of work and donate money to both coalition-oriented organizations and to organizations that mount a principled defense of free speech. But it’s really challenging for a single entity to do both at the same time.

On that specific issue, fortunately, FIRE has grown beyond its original campus mandate and stepped into the free speech space vacated by the ACLU.

But many causes are arguably best served by a kind of bifurcated strategy. Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America primarily tries to help Republicans win elections, which makes sense given the large partisan gap on reproductive freedom policy. That said, even though there’s a strong case that Democrats should be trying to recruit anti-abortion candidates like John Bel Edwards in the Deep South, the anti-abortion movement is so enmeshed in the broader ecosystem of conservative politics that they aren’t making that case. Similarly, pro-choice groups largely refused to work with Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski on their effort to craft federal abortion rights legislation. Neither side can actually get federal bills passed because they’re so wedded to all-or-nothing strategies and grand coalitions rather than trying to find members on the other side they can collaborate with.

The strong logic of bipartisanship

One of the oddities of our increasingly rigid party system is that the logic of American political institutions still militates in favor of most policy change being bipartisan. The filibuster plays a role in that. But more fundamentally, the importance of bipartisanship stems from the fact that we have geographically defined legislative districts, weak party control over nominations, and an open and entrepreneurial political system. If you want any kind of reform that results in concentrated losses and diffuse gains, you’re going to find that the very large number of veto points gives those who want to avoid concentrated losses lots of opportunities to block change. You can get around that by elevating your issue to the very tippy top of your party’s agenda, and then getting your preferred party to win a trifecta, but that’s hard.

The other way to do it is to make your cause bipartisan. When there is sincere buy-in from energetic legislators on both sides of the aisle, there is often a way to get something done. When that buy-in isn’t there, it’s much harder.

To bring this back to YIMBYs, as best I can tell, the biggest difference between states like Maine, Washington, and Texas that are putting big wins on the board and those like New York and Maryland that aren’t, is bipartisanship. It doesn’t technically make a difference. With a trifecta, you could just pass a really good one-party bill. But I do understand that practical politicians tend to be cautious in their expenditure of political capital. Indeed, I’m often in the position of urging Democrats to be more cautious, so I need to acknowledge that the case for caution applies even to my pet issues. One of the strengths of housing reform as a topic, though, is that the best way to be politically safe is to do things that are bipartisan, and land use is a topic with a lot of potential scope for bipartisanship.

Of course, the point of the Elmendorf/Schleicher proposal is to try to embed YIMBYism in a broader nexus of moderate urban reform causes, which is certainly consistent with bipartisanship. And as I said, I would genuinely love to see more funding flow to the creation of multi-issue organizations along the lines they’re suggesting. But per Brian Hanlon’s points here, even in that context, I think there’s real value in sustaining genuine single-issue housing organizations.

One of their core arguments is that support for allowing density is strongly correlated with personal preference for city living, so making cities more appealing with safer streets and better schools will build support for YIMBYism. I agree with that. But the converse is also true, that in practice, YIMBYism finds a lot of support among people with a personal preference for city living, which, in practice, is mostly people with left-wing politics. I would love to persuade those people that they are wrong about important aspects of criminal justice and education policy. But if you made sharing my views on those topics the price of admission to the YIMBY coalition, I’m afraid we’d just lose a lot of people.

Conversely, successful YIMBY bills get a lot of support from people who aren’t “urbanists” at all and don’t care about things like mass transit.

North Carolina’s lower house passed a sweeping parking reform bill in June that, if it passes the state senate as well, will leapfrog New York City on this issue, because reformers in NC completely detached it from anything related to transit or urbanism. Of course, in the short-term, parking-light projects are still mostly going to be built in places where there’s good transit, which means that most projects in North Carolina are still going to include tons of parking. But self-driving cars may completely detach off-street parking from the concept of walkable urbanism. It’s just good economic policy to adopt flexible land use rules in advance of technological change.

At any rate, I’m well aware that this is an annoyingly ambiguous in which I am refusing to take my own side of the argument. I’ve often been frustrated by blue state YIMBYs who are excessively focused on bolstering their “we’re the true progressives” credentials rather than on building bridges with moderates. I want the kind of para-party that Elmendorf and Schleicher are talking about to exist.

But mostly, I think the whole space of land use is massively under-funded relative to its objective importance, and we should both have multi-issue moderate urbanism organizations and single-issue housing policy groups. Because I agree that in some sense, the non-housing problems of urban governance are a limiting factor to long-term YIMBY success. But I also think YIMBYs have put a lot more points on the board than almost any other contemporary movement, precisely because we’ve pursued a single-issue strategy in a polarized era.

The bagel that most nearly replaces the everything bagel while still remaining a single-flavor bagel is the onion bagel.

This is a self-evident truth on which all people of good will can agree.

YIMBYism should rebrand as promoting construction jobs, which is obviously literally true. 'Getting rid of NIMBYism creates good-paying blue collar jobs locally' is a popular message- Americans love job programs. Construction can be OK paying, sometimes lucrative for skilled trades, but also can't be offshored, seems to have low automation potential, etc. It should be a great replacement for factory work. It's also a very willing employer of men from tough neighborhoods, men with criminal records, etc. You think a roofing crew cares if you have a felony?

If YIMBYs could get construction workers to testify in favor of building projects, it'd help sharpen their message and push on the class divide a little bit- it's usually the upper middle class that's *against* construction in their neighborhoods. OTOH, I can't imagine the average YIMBY I know or see online have an actual conversation with someone in the trades, so that alliance might need a little bit of work