The widespread ownership of guns in the United States is the predominant reason we have so much more homicide than the developed countries of Europe and Asia. Differential availability of guns also largely explains why, inconveniently for Republicans, there is generally more murder happening in red states than in blue ones.

The standard GOP cope is to argue that the murders are happening in “blue cities,” but that just reflects the fact that essentially all cities are blue in the contemporary United States. When you look at the rare city with a Republican mayor like Jacksonville in Florida, you see a lot more homicide than in New York. That’s because criminals aren’t magicians or kung-fu masters; their ability to kill people depends on their access to lethal weapons. And unfortunately there is substantial interplay between the legal market for guns and the black market for guns. The NYT ran a great piece last week about the large number of guns used in crimes that are stolen from parked cars — the more guns floating around, the more people get shot. Morgan Williams has a great paper looking at a gun policy reform in Missouri where the state legislature made it easier to buy guns legally with the result that shootings surged in Kansas City and St. Louis. Non-gun homicides actually fell because assailants were equipping themselves with better weapons. But precisely because guns are more deadly than knives or bats, this generates an overall increase in death.

Do note, though, that essentially all of this action is being driven by handguns.

The big long guns, including those with features that would get them tagged as “assault weapons” and also long guns without those features, are collected by hobbyists for use in tacky family photos. They’re stockpiled for use in a hypothetical civil war. They’re used for fun. And occasionally (though still far too often), they are used in a rare-but-spectacular spree killing that electrifies the nation because it affects middle-class suburbanites who are unaccustomed to having their lives impacted by violence. These guns are too big and too expensive, though, to be the weapons of choice for “ordinary” crime — the type responsible for the overwhelming majority of gun deaths in the U.S.

That they are so frequently at the center of our national gun debate strikes me as an understandable reaction to horrific events. I’m a dad with a kid in school and I feel this anguish in my gut and I see it in the eyes of my fellow parents all the time. I get it. But the focus on the very most spectacular events to the exclusion of “normal” shootings generates bad policy analysis. We have policy solutions at our disposal that would address the proliferation of illegal handguns that drives the bulk of gun deaths in this country.

The limited relevance of assault weapons

Public opposition to banning handguns is overwhelming. It’s also unchallenged by any remotely mainstream Democratic Party politician, which seems like a reasonable response to the reality of public opinion.

But that means thought-leaders on the left need to exert some discipline and mindfulness when they post about newsworthy shootings. I fully endorse the implication of this chart Steven Rattner posted, which is that the large aggregate number of guns in the United States is why the United States has so many gun deaths. But a majority of these gun deaths are suicides, and a very large majority of gun homicides are committed with handguns. So as an intervention in the debate about assault weapons, it loses some of its persuasiveness.

When high-profile commentators like Rattner say this stuff — and even more so when they are amplified by someone like David Axelrod, who is arguably the single most successful and respected progressive political strategist — it sends a powerful signal to the audience for progressive political commentary that this is a fruitful messaging direction.

But is it? A federal assault weapons ban, if passed, would have a minimal impact on that “gun deaths” number. A federal assault weapons ban also isn’t going to pass. Sometimes it’s politically constructive to discuss things your opponents in Congress are going to block. But a high-profile national debate about assault weapons doesn’t help Jon Tester and Joe Manchin and Sherrod Brown get re-elected. It’s probably bad for Bob Casey and Tammy Baldwin and Elissa Slotkin, too. We also know that media coverage of mass shootings and post-shooting gun control debates leads to an increase in gun sales. So while Rattner and Axelrod posting that chart is good for social media engagement, it’s probably counterproductive both in terms of partisan politics and in terms the actual quantity of guns around.

And again, while it’s absolutely true that the volume of guns and the volume of gun deaths are closely related, that relationship is not driven by high-profile mass shootings or the regulation of assault weapons.

It’s also important to note that when you post something misleading, you are much more likely to mislead your base than your opponents. Conservative gun enthusiasts are aware of what’s misleading about this chart. Liberals are the ones who develop the mistaken belief that a modest, slightly popular federal gun regulation would dramatically reduce the level of lethal violence in the United States when that actually isn’t true. Everyone is entitled to push for small-bore change with modest upsides, and banning assault rifles would absolutely be a good idea. But it’s not a good idea to fool yourself about what’s at stake in your own policy proposal. Meanwhile, if we want to reduce the number of handguns floating around, we have options.

When guns are outlawed …

Something that I don’t think most normie Democrats realize is that at some point in the past 10 years, the criminal justice reform wing of the progressive coalition decided that arresting people for carrying guns illegally is bad. In the Prison Policy Institute’s mass incarceration pie chart, weapons charges are listed as non-violent public order crimes.

Keith Alexander recently wrote a piece for the Washington Post about the shocking discovery that the US Attorney for D.C., Matthew Graves, is declining to prosecute two-thirds of the cases that MPD brings to his office. In response to Alexander’s question, Graves reassures us that these are not violent crimes he’s letting slide:

Graves said the declinations are mostly coming after arrests in cases such as gun possession, drug possession and misdemeanors — not in violent crimes. He said his office last year prosecuted 87.9 percent of arrests made in homicides, armed carjackings, assaults with intent to kill and first-degree sexual assault cases. According to figures provided to The Washington Post, that percentage is higher than the 85.7 prosecuted cases in 2021, but down from 95.6 percent of prosecuted cases in 2018.

Note, again, that in this framework, gun possession is considered a non-violent offense. Just before the latest mass shooting re-ignited a national debate about assault weapons, the Marshall Project published a big feature complaining about gun possession arrests, arguing that this drives the racial disparity in incarceration. Larry Krasner, the progressive prosecutor running the show in Philadelphia, takes the same view and, like Graves, has cut down on gun possession prosecutions.

The view that having lots of people walking and driving around town while in possession of firearms isn’t a problem is, of course, a relatively mainstream view in American politics. But it’s the conservative view. If conservatives had their way, anyone living on the South Side of Chicago could easily walk into a gun shop and buy a handgun that he’s then free to carry, openly or concealed, wherever he wants. Most residents of Illinois and of other progressive jurisdictions recognize that this would have the downside consequence of a lot more murders. Again, per Williams’ paper, this is exactly what happened when Missouri liberalized gun laws — more people got guns legally, which meant more people got guns, which meant more people got shot. Note that in Williams’ data, virtually all of the additional homicides had Black victims.

I really think the leaders of the progressive movement need to get a bunch of stakeholders and smart people around a table and try to decide what we’re saying here.

If the incarceration generated by arresting and imprisoning people for carrying guns is intolerable, we should legalize carrying guns, aware that this will lead to more murder.

If “guns are the problem” and the high level of gun violence in the United States is intolerable, we should insist on arresting and prosecuting people carrying illegal guns.

My read of the situation is that the current level of incoherence results largely from sincere confusion. We know, for example, that Joe Biden is a crime moderate and always has been. We also know that Biden is not a gun control moderate. And yet it’s a Biden appointee working as U.S. Attorney for D.C. who’s decided that declining to prosecute gun possession cases is no big deal. The gun control people and the criminal justice reform people are working on separate tracks, and not enough attention is being paid to the need for politicians to craft a coherent account of what they’re trying to accomplish.

I do want to note for the record that the reformers have an explanation for how they reconcile their orthodox anti-gun view with their objection to enforcing gun laws. Their theory is that first you pass a national ban on the manufacture or sale of guns to civilians. Then you back it up with a mandatory buyback. The buyback won’t really be enforced (prison is bad!), but nonetheless a large fraction of the population will voluntarily comply. That automatically reduces the number of guns in circulation, and over time the police will seize more guns in the course of arresting violent criminals, and since the legal supply of new guns has been cut off, the swamp slowly drains, even if nobody is ever arrested for gun possession.

That’s a nice story, but it’s lightyears from any form of social, legal, or political reality in the United States. In practice, authorities face a tradeoff between strictly enforcing gun laws and accepting more gun violence.

“Broken Windows” helps you find illegal guns

I’ve been in Chicago for a fellowship the last few weeks and recently rode the CTA Green Line into the Loop from the South Side. Few people were riding the train and many of those who were were smoking. That made me think of the revival of interest in “broken windows” policing and routine public order enforcement.

My read of the evidence is that the main broken windows hypothesis (that disorderly conduct like people smoking on the L leads to serious violent crime) is probably wrong. That being said, I personally found it kind of unpleasant to be riding in a hotbox train car. My guess is that we made it illegal to smoke on trains because people found the smoke annoying and wanted people not to do it, and that seems like a perfectly valid reason to me. Back in 1998, I saw tons of people breaking the rules and smoking on the Metro in Paris. There was no violent crime problem associated with this (no guns!), and at the time I didn’t mind (I was a teenaged heavy smoker), but people are entitled to set standards of conduct for their mass transit system and enforce them.

Where I do think “broken windows” helped contribute to the 1990s crime drop is that when you arrest someone for some obvious crime, you can pat them down and see if they have a gun.

The first-order impact of this, yes, is to increase the number of people in prison for non-violent offenses. But the second-order impact is you start deterring people from carrying guns. The third-order impact is that because there is less gun-carrying, people feel less threatened by gun violence so their own risk-reward function shifts in favor of not carrying a gun. This strategy brought violence down a lot, and I think in high-crime cities it should be revived. It’s also a strategy that faces diminishing returns, at which point some departments (mostly famously the NYPD in New York) implemented “stop and frisk” in high-crime neighborhoods, targeting people who weren’t committing crimes. I think it’s very easy to understand why this angered the people targeted (overwhelmingly Black and Hispanic men) and their loved ones.

Stop and frisk was halted by federal courts, and contrary to the fears expressed by the NYPD, shootings didn’t go up.

I think the main lesson here is really that New York City, which is unusually heavily policed and much safer than the average American city, was at a point before 2020 where it was hard to make further safety gains by cracking down on gun-carrying. In general, the country as a whole had made a lot of progress against violent crime but still had a lot of it compared to other developed countries. A good reform idea would have been to try to start pivoting to something more like Thomas Abt’s “focused deterrence” concept that tries to be less blunt in terms of who police target. But in general, I think we have reason to believe that a campaign of rigorous enforcement of the rules is a good way to find illegal guns and that people who have illegal guns should be punished. That doesn’t fix everything, but it does a lot of good and aligns much better with the “guns are the problem” diagnosis than a ban on assault weapons does.

Policing a gun-rich society

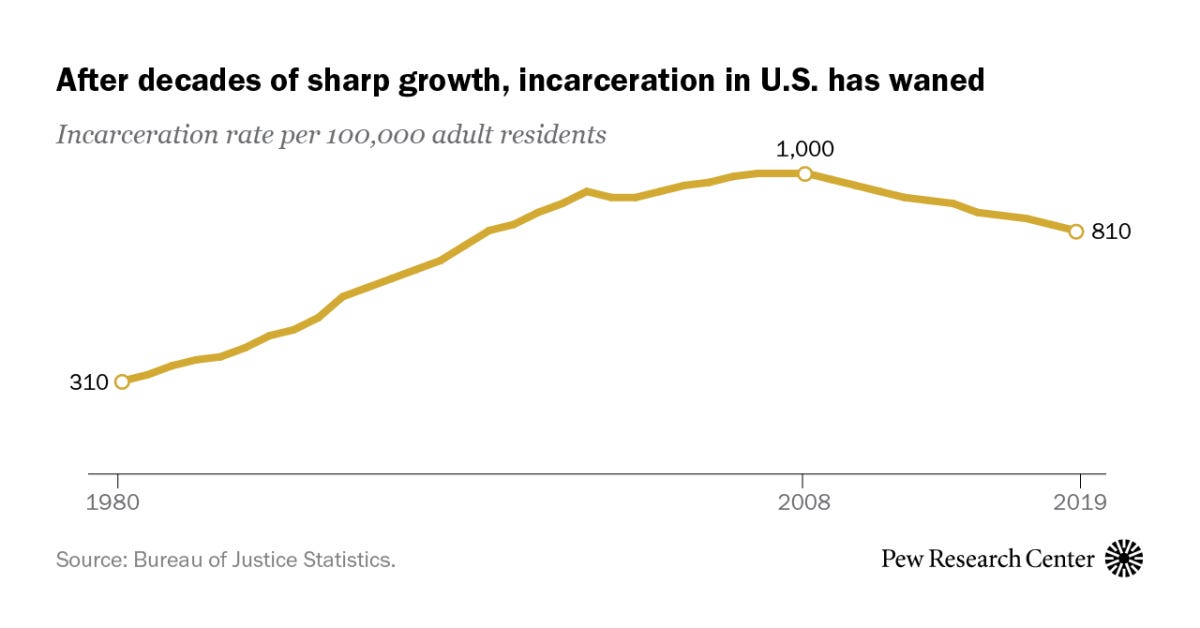

I think it’s really worth emphasizing that incarceration was falling before 2020 under an urban policy regime that emphasized strict street-level enforcement and arresting people for illegal gun possession.

Some of that decline is because we started legalizing drugs, some of it is because a few states made prison sentences shorter, and some of it is because fewer people were getting shot, which led to fewer people doing hard time for serious crimes.

The goal of strict enforcement of the handgun rules, at the end of the day, isn’t really to incarcerate some huge class of handgun carriers and keep them off the streets. It’s to create a situation where fewer people have guns, and therefore various neighborhood disputes and gang beefs are less likely to turn into shootings. It seems to work pretty well. But if you think it’s unconscionable to put people in prison for carrying guns, then it would make more sense to throw in with the conservatives and actually make it legal. To be clear, though, that’s a bad idea. Progressives are right about guns, and we ought to act like we’re right and re-embrace the successful strategy of enforcing gun laws.

It’s also just a fact of life that as long as the country is more awash with guns than other peer democracies, we are going to have a higher risk of violence and we’re going to need more policing and more incarceration. That’s regrettable, and I would hope over time to tighten the gun laws at both the state and federal levels. A good part of an iterative campaign to achieve that, though, is to demonstrate that gun regulation can work and can be vigorously enforced and that trafficking and carrying illegal guns is not a harmless activity.

There is no gun debate. There is only demagoguery masquerading as debate. It is boring, not in the slow-boring way, but boring because it is all a rehash with no real path to resolution.

Prosecutorial discretion, though, is a real issue with concrete examples that permeate multiple policy issues. Our lazy acceptance of prosecutorial discretion is driven by a good faith understanding that we have more laws than resources to enforce them, so some picking-and-choosing is to be expected. That has historically been true for prosecutorial discretion in most cases, but this has changed a lot over the past 15 years in ways that are really bad for our system of government.

When used as a way to advance policy, as is happening in D.C., prosecutorial discretion is a perversion of justice and undermines democracy. If representatives cannot pass a law and expect it to be "faithfully executed", then we cease to be a nation of laws at all. If the executive branch chooses to ignore some laws because they, and not the legislature, think the law is wrong then that is dangerously close to authoritarianism, with the application of the law being subject to the whims of one person alone.

To paraphrase the headline of today's essay: "The policy-driven prosecutorial discretion is the problem"

Every legal gun owner in the United States knows this. This is literally the conversation whenever gun owners talk about gun control.

It’s the most obvious, yet under discussed issue whenever gun control is discussed. And one of the main reasons gun owners say things like... 1st enforce the laws you already have before making new ones.

Of course, it will never happen.

Disclaimer: I own several guns. All locked away in a safe. I don’t shoot nearly as much as I would like, but it is fun.

Side note: nothing compares to Alaska for open or concealed carry or firearms. Though the little town in Eastern Oregon that my cabin is in comes close.