The humanities should be harder

Low standards have devalued non-STEM study

If you major in philosophy, as I did, you will inevitably get jokes about whether they’re hiring at the philosophy factory. The truth, though, is that philosophy majors have above-average earnings compared to the typical college graduate. And that’s not just a function of would-be philosophers going to law school. People whose terminal degree is a bachelor’s in philosophy earn pretty good money.

Most philosophy departments have a line about this, pitching students on the very real value of the skills that philosophy undergraduates practice.

I don’t think those departmental lines are wrong, exactly. Skills like reading texts closely, understanding the logical structure of arguments, and writing persuasively certainly do come in handy in a wide range of settings. That said, I don’t think this explains much about the relative earning power of a philosophy degree. The skills you learn studying history — reading documents, evaluating evidence — are also broadly applicable. What’s interesting isn’t that philosophy-type skills have some utility, it’s that philosophy majors earn more than history majors or English majors or students of other traditional, non-STEM academic topics.

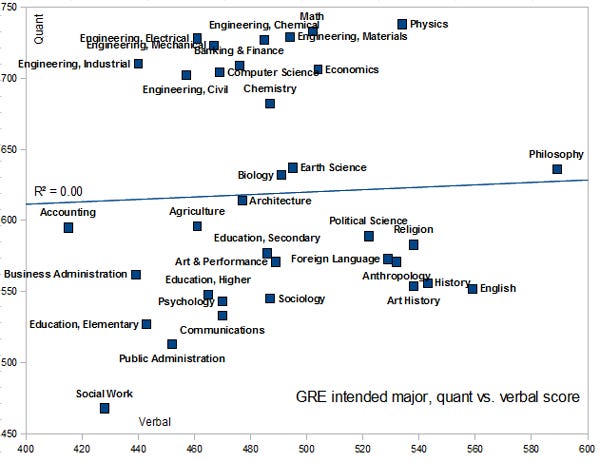

And I think Scotty Hendricks nailed the explanation in a Big Think piece he wrote a couple of years ago: philosophy majors earn more because philosophy majors are smarter, on average, than students of other traditional liberal arts disciplines.

But why are philosophy majors smarter?

I don’t fully understand the historical or sociological factors behind this. Whatever the factors are, though, they are highly contingent. Philosophy professors have higher GRE scores than professors of English or history or sociology. They run classes that are relatively difficult and that dissuade people from pursuing the major unless they’re smart and hardworking. Philosophy graduate programs don’t have many slots to offer, and the few slots they have go to people with high GRE scores. And the cycle continues.

I was thinking about this the other day when I saw a round of Twitter discourse expressing frustration that English and history students don’t get the same respect as STEM students

.

I believe deeply in the value of studying literature and history and philosophy and big ideas. And DOGE just gave the entire country an object lesson in the dangers of Arrogant Smart STEM Guy Syndrome.

But if you want respect, you need to earn that respect. The way to make humanistic learning more respected and prestigious, it seems to me, is to make the classes harder. Assign more work. Grade the work more harshly. Get the laziest and dumbest students to opt out. And then repeat the cycle.

The gut-course equilibrium

This is a touchy subject, so I want to be clear. I’m talking here specifically about undergraduate education. What happens beyond that, I have much less information on, and the relevant considerations seem different.

And I’m not saying that studying undergraduate-level humanities is inherently easier than studying a science or engineering topic.

In fact, I’m saying the reverse.

At an undergraduate level, colleges can make courses as arbitrarily difficult or easy as they want. And in practice, science departments choose to make their classes hard. Science faculty have grant money to do research and run labs. That’s great, people like to have money. But administering labs and writing proposals is also a lot of work. The people doing this stuff don’t really care how many undergrads want to take their classes, and have no particular desire to spend their time dealing with subpar or un-motivated students. So the norm in these departments is to have challenging courses that “weed out” or scare off weaker or less motivated students.

The downside of this arrangement is that the actual quality of the teaching is often pretty bad. The professors don’t care if anyone enjoys their classes, and the grad students have job opportunities in the labs rather than just as teachers. But the upside is that if you study physics and get passing grades, you’re going to learn a lot of physics.

What’s more, when I tell people Kate majored in physics at MIT, most of them think, “oh wow, she’s smart,” not “wouldn’t an English major be more qualified to edit your blog?”

Humanities departments are in structurally worse financial shape. The faculty don’t have the same scale of research grants coming in. And they can’t tell the world that their work is curing disease or winning wars or unlocking new forms of clean energy. They genuinely want students to enroll in their classes, because teaching is their calling card. But if you want students to enroll in your classes, you have to give the customers what they want. And while that isn’t necessarily “easy classes,” it’s definitely “good grades,” and over the long term, the only way to give people the good grades that they want is to make the standards low.

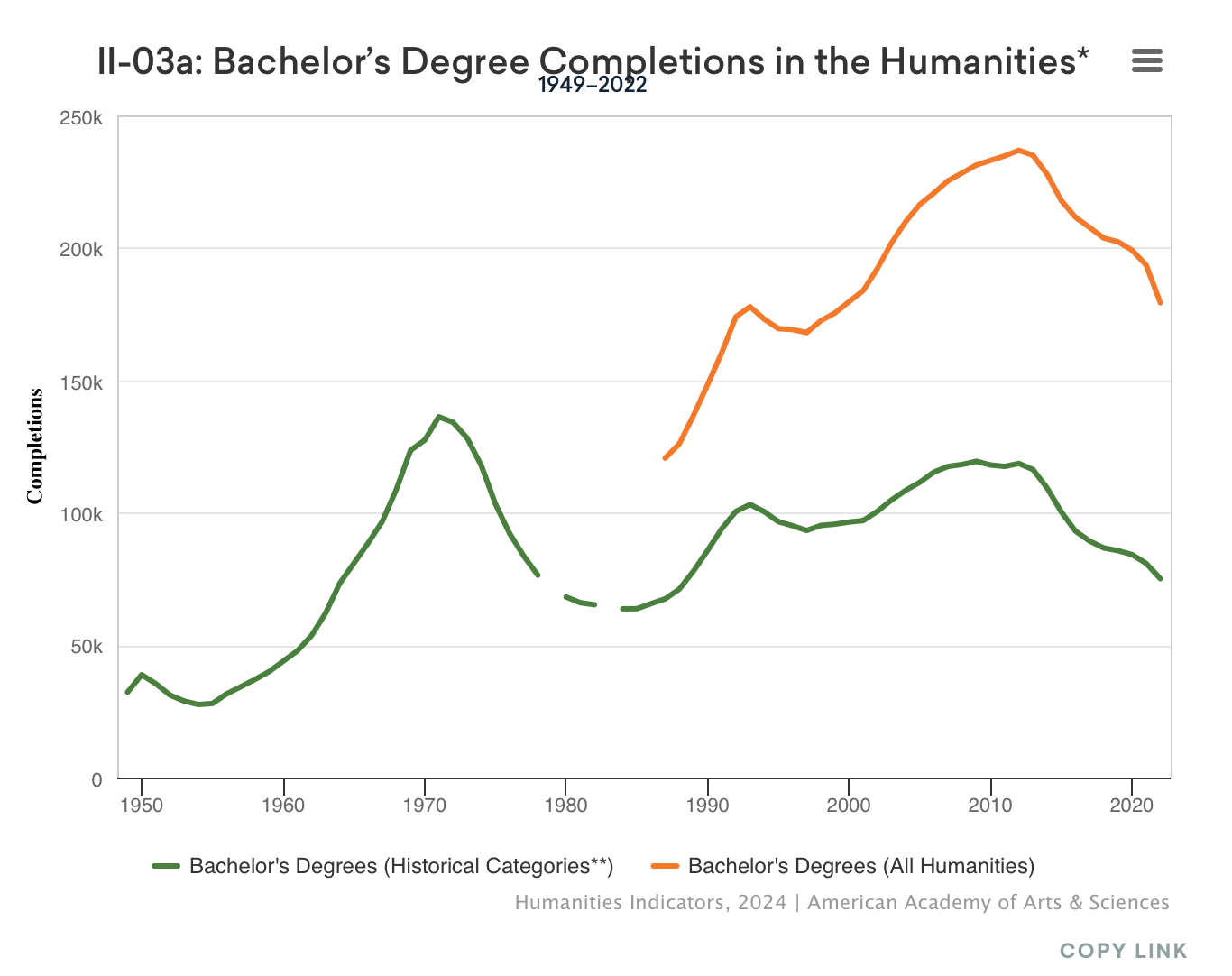

This worked well enough for the relevant stakeholders for a long time, but it’s now sort of falling apart. The chart below shows the number of bachelor’s degrees awarded in the traditional humanities disciplines (classics, English, history, foreign languages, linguistics, and philosophy) and, in more recent years, for a wider range of new humanities majors. Both have been tumbling for the past 10–15 years as students lose faith in the value of these degrees.

I know some people welcome this as a sign of growing pragmatism on the part of students. But I think there’s something tragic about this loss of interest. And I think that too much pandering to market demand has ultimately been self-defeating. Lots of people would like to get good grades without working that hard, but the reason they want that is they think the degree will have value. But the value of a degree is tied up in the idea that you need to be smart and hard-working to get one.

Making classes harder seems easy

A 2024 Atlantic article by Rose Horowitch argued that a shockingly large share of contemporary undergraduates at selective colleges struggle to read complete books. She blamed high schools for this, which she said have backed away from assigning whole books, which she in turn blames on various education policy choices. I think Michael Petrilli convincingly debunked that explanation, and I know there was a lot of debate among academics as to whether Horowitch was overstating the extent of the phenomenon.

But almost everyone seemed to agree that the phenomenon is real, and that the brain-scrambling impact of smartphones and ubiquitous short-form video clearly has something to do with it.

On some level, if students are struggling to read whole books, the solution is for professors to assign whole books.

A kid who’s capable of getting a good SAT score and getting into a good college does, in fact, have the basic capacity to read a long book. But he very well may not have the discipline or habits of mind to actually do the assignment. That’s what school is for, though, to learn things, including discipline and habits of mind.

Probably nothing in your life will ever actually hinge on whether you can read The Odyssey and come up with something intelligent to say about it. But educated people have been doing this for centuries. It’s a proven exercise. And apparently, now more than ever, we need to put students through the paces on this kind of exercise, since we are well past the era when reading books for pleasure is the most enjoyable entertainment available.

Which is certainly not to say that I fetishize reading whole books. I remember well my two-book set of D.D. Raphael’s edited volume “British Moralists: 1650–1800,” which is all excerpts. But it’s excerpts from Hobbes and Locke and Hume and Bentham and lesser-known figures like Bernard Mandeville and Francis Hutcheson, plus a selection of Adam Smith’s work on moral philosophy, which is less well known than his economics. Again, a person will get by just fine in life without reading this. But it’s a good exercise for your mind.

And I think reading really is like exercise. If you’re going to lift weights, you’re supposed to exhaust your muscles. If you’re going to run, you’re supposed to run fast enough to tax your cardiovascular system. Exercising is hard work, because the point is to work hard. If it’s not hard, you’re not doing it. And college should be like that. Getting good grades should require significant effort. People who are dumb or lazy should be getting bad grades and flunking out of school.

Better fewer, but better?

The risk of higher standards and more rigorous grading, of course, is that fewer people will complete college. But that seems fine.

I don’t care for the schtick where college graduates who desperately want their kids to go to college write articles for other people who went to college, where the thesis is “maybe we shouldn’t have so many people going to college.”

So I’m really not trying to gatekeep or argue that only a select few should be pursuing degrees in history or English or other liberal arts. But I think that if you want to see people studying these subjects, you have to make their study valuable. And for it to be valuable, the programs need to be rigorous.

To go back to the joke about the philosophy factory, I don’t think we should be haunted by the specter of a world where students come out of college incredibly well informed about George Eliot or W.V.O. Quine or the history of the Holy Roman Empire or Sophocles or the role of women in Meiji Japan or whatever other “useless” topic you can think of, and then find themselves unemployable. This is a fake problem. The problem stalking the humanities is a suspicion that students are coming out of school with humanities BAs, but without an impressive level of knowledge about their ostensible topics of study.

Lowering standards and dumbing things down was a fake solution to the mostly fake problem of alleged uselessness — if the English department couldn’t offer you valuable job skills, it could at least offer you an easy path to a degree.

But making it easy denudes the degree of value, as if a gym mislabeled all their weights to make it easier to put up big numbers on your bench press. Obviously everyone would love a gym where they’re always setting miraculous new personal bests. But once you figure out you’re not actually getting stronger, that model is going to collapse. Right now, a lot of what’s going on looks to me like universities trying to catch a falling knife of prestige, with certain departments responding to waning interest in the classics by doing things like removing the requirement that classics majors learn Greek and Latin. Traditionally, I think doing well as a classics major was impressive precisely because you had to do difficult things like learn dead languages. If you lower the bar, what’s the point?

I don’t think it’s even remotely knowable ex ante where the popularity of humanities programs would settle if we raised the bar. Initially, colleges would almost certainly see a drop in enrollment. And the drop might be sticky with humanistic knowledge becoming a kind of esoteric activity maintained by a small elite. I think it’s at least possible, though, that if a humanities education were treated as valuable by educators — significant workloads, high standards, some level of common canon that students across schools are expected to master — that students and society at large would discover the value of pursuing it.

As a squishy humanities-inflected social science guy who never shuts the hell up on this topic here, I agree 10,000%. But four caveats:

- the risks of being a first mover on tougher standards, either as an individual educator or institution, are immense while the possibility of payoff is remote;

- as long as there is an insistance that undergraduate education must be evaluated solely in terms of monetizable societal benefit, the above risk / payoff ratio becomes even more lopsided;

- everyone has to accept the possibility that it is their child who will decisively wash out of any such higher-standard program, dyslexia or other verbal/literacy difficulties nothwithstanding;

- without succumbing to The Discourse on AI in education in either direction, I'm just going to say "embrace AI as a productivity-enhancing technology" and "significantly increase the rigor of undergraduate humanities education" are, at best, two goals that are hard to reconcile with each other.

Professor in a humanities discipline at a research university here. I love the idea in principle, but here is the practical problem.

My Dean has made it clear that what matters to him when making decisions (especially decisions about whether to replace professors when they leave or retire, what kinds of financial support for department activities etc.) is “metrics”. And he has said openly that the single metric that matters most in this context is class sizes - how many students the department teaches.

So if we make our courses so hard that our enrollments collapse by half, we will lose massively. So our strong incentive is to keep enrollments high, which is best done by not making it unfeasibly hard to get a good grade.

This does mean that our major looks less prestigious, for the reason Matt explained, so we attract fewer majors and probably lower quality students doing those majors. But the Dean doesn’t care about that, provided the overall undergraduate numbers hold up via our elective courses.

The way I handle this personally is by still setting whole books, lots and lots of reading, and making it clear that I want people to do it - while at the same time setting papers, exams etc. that students can do well on even if they haven’t done all the reading.

And yes, I’m aware of a certain inconsistency in this, but it’s the best I can think of, given the pressures on me.