Today is either Columbus Day or Indigenous People’s Day depending on exactly where you live and per usual for federal holidays, Slow Boring is going to take the day off and bring an old article out from behind the paywall. Today’s offering is a history of third parties in America, written back when Joe Biden was going to be the Democratic Party nominee, making the point that two presidential nominees being unpopular was neither necessary nor sufficient to making a third party bid viable.

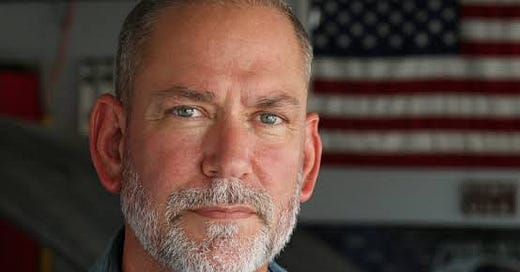

But I also wanted to talk about Dan Osborn, an independent who is making a real go of challenging Deb Fischer in Nebraska. His polling has been looking really good recently so he’s about to get hit with a ton of Republican Party super pacmoney and he could really use hard money from moderate small donors.

I’ll probably write more about Osborn soon (he probably calls it Columbus Day), but just to note in the context of this post that I think the Osborn route is how third parties could make a big difference in reducing American polarization. You could imagine a small caucus featuring people like him, Lisa Murkowski, and Jared Golden both holding the balance of power in congress and also serving as a pole of attraction for other members who have moderate instincts but currently don’t see any path to upward mobility other than playing to their side’s respective groups.

When I wrote about the failures of No Labels as a moderate political play, I wanted to focus on constructive suggestions for what moderate donors could do, and not get bogged down in why spoiler campaigns are dumb in the context of the American political system.

But I do think the broader question of third party campaigns is worth engaging with on its own terms, because the United States is kind of an outlier here.

First-past-the-post electoral institutions obviously discourage third party voting relative to highly proportional systems. But most FPTP countries that I’m familiar with have a decent amount of third party voting, and at times even see third party representation in their legislation. One reason the Tories in the UK are poised for such an extreme drubbing is that not only is Labour pretty popular, but the Tories are bleeding votes to a right-wing splinter party. A couple of elections ago, the UK was governed by a coalition government because various third parties did well enough to ensure that nobody had a majority. Canada right now has a Liberal minority government that has been relying on limited cooperation with a left-wing third party to pass legislation. France has an upcoming legislative election in which strategic party alliances and tactical voting are a huge deal, and their most recent second round presidential election was between two different “third parties,” with the traditional center-left and center-right both locked out.

There are institutional differences that help explain this kind of thing, but it’s also an area where I’d be inclined to push against over-indexing on structural explanations and under-indexing on contingencies and the quirks of history. I don’t think it’s that hard to imagine a world where Donald Trump ended up being a third party candidate — or one where Emmanuel Macron never bolted the Socialist Party to become a third party winner.

A major reason US third parties are so marginal right now, I think, is that we simply haven’t seen the right alignment between ambitious personalities, the relevant structural features, and an interest in building real institutions. Instead, third partyism seems to suggest itself in a highly personality-centric way — which is really the opposite of what a political party is for and goes against the grain of American institutions, where there’s nothing really stopping a charismatic and forceful politician from waltzing into an established party and winning primaries. To understand where opportunities for third party success might lie, it’s useful to look at history — because third parties really have had significant influence in the past.

When do third party candidates succeed?

One major fallacy of No Labels-ism is that it’s based on the intuitive-sounding idea that both major-party candidates being unpopular creates a strong opportunity for a third party.

There’s a real logic to that, but I think it’s defied by history.

Consider the 1992 presidential election. Bill Clinton won with a pretty pathetic 43 percent of the popular vote, which Republicans used in 1993-1994 to promote party unity by arguing that he had no mandate. But note that in late October of 1992, Clinton was viewed favorably by a 64-33 margin in Gallup’s surveys. So even though most people didn’t vote for him, he actually enjoyed a far stronger base of support than any Trump or Biden has ever had. Not only that, George H.W. Bush, who Clinton beat, was at 61-39. People were, in fact, disappointed with his handling of the oil shock recession, and Republicans had been in office for 12 years, so there was plenty of Bush fatigue. But people didn’t hate him. He was seen as a moderate and pragmatic Republican who generally handled foreign affairs well.

Ross Perot did well not because people hated the two major-party nominees, but in part, precisely because they were both seen as moderate and sensible. Perot spoke to a distinct and essentially proto-Trumpy constituency that was mad about globalization and skeptical of establishment politics. But the other thing that helped him get votes was the difficulty of convincing soft Republicans to be terrified of Clinton or soft Democrats to be terrified of Bush. And I think if you look at the other really big third party years — 1912, 1924, and 1968 — you see something similar. In particular, all three 1912 candidates kind of positioned themselves as progressives (in the sense that was meant at the time), while both parties nominated conservatives in 1924, so LaFollette got a lot of traction as a progressive.

In 1968, Humphrey was moderate on the war, Nixon was moderate on domestic policy, and neither opposed the Civil Rights Act, so there was a door for Wallace. If Democrats had nominated someone more left-wing, Nixon would’ve had an easier time consolidating the Wallace voters into his camp (as happened in 1972). And if Democrats had nominated a leftist and Nixon had run on rolling back Medicare and Social Security, then most people would have held their nose and picked the major party nominee they hated least.

There is one example — John Anderson in 1980 — that comes close to the “voting third party because the major nominees suck” model. In that year, an unpopular incumbent faced off against a GOP nominee who was seen as coming from his party’s extreme wing. Anderson, a moderate Republican, bolted the party and wound up hurting Carter by giving people who didn’t like Reagan a shot at casting an anti-Carter protest vote. But note that Anderson got many fewer votes than Perot or Wallace — even somewhat fewer votes than Perot’s second run in 1996.

A dislike of the major party candidates simply has not driven the most successful third party bids. People vote for third party presidential nominees less because they hate both major party choices than because they don’t see a strong contrast between them. Trying to run up the middle in polarized conditions is extremely unpromising.

Third parties in congress

Given the way American institutions work, I find it slightly more interesting that third parties have historically had such limited impact on Congress. If you go way, way back to the time before the Civil War, the Anti-Masonic party and the anti-immigration Know-Nothing party did periodically challenge the Democratic-Whig duopoly. But since then, third party impact has been extremely marginal.

And we know in general that the pre-war Whig Party was a pretty rickety construction. They won a couple of presidential elections by recruiting military men (William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor) to run on their line, but never got a major Whig leader like Henry Clay elected. Eventually, they were replaced by the Republican Party as the opposition to the Democrats. But part of what you can see on this chart with the surging Know-Nothing wins in 1850 is that the Whig Party was already dying when pro-slavery Democrats passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. The original leaders of the GOP — William Seward, Salmon Chase, Charles Sumner, and Abraham Lincoln — were almost all ex-Whigs, and in their first presidential campaign, they went for the classic Whig tactic of nominating a general.

But while the old Whig Party had been designed to attract the broadest possible coalition against Andrew Jackson (including pro-slavery southerners), the Republican Party centered the anti-slavery issue and tried to assemble the broadest possible coalition against expansion of slavery into the territories. That was good enough to get America’s abolitionist minority to vote for the new party in a way they’d never wanted to vote Whig. The new party was also very clever about disproportionately putting forward ex-Democrats as their actual nominees in races. The voting base and the top leadership were mostly ex-Whigs, but the key target voters were Northern Democrats who wanted to keep slavery out of the west, so they tried to put those faces forward.

This worked, obviously, but since then, third party representation in Congress has been fairly minor. The Populist and especially Progressive (“Bull Moose”) social movements were influential, but they didn’t really get off the ground as partisan projects. A big reason for that is American parties are unexpectedly resilient, in part because they are so formally weak.

Parties bend instead of breaking

We don’t generally spend a lot of time thinking about the 1894 midterm elections, but they really illustrate the limits and promise of third party politics.

During and after the Civil War, Republicans mostly dominated American politics, winning the White House in 1860, 1864, 1868, 1872, 1876, and 1880. Finally, in 1884, Grover Cleveland won as a Democrat. Republicans at this point in time supported a high tariff to protect industry, believed in using the revenue generated by that tariff to pay generous pensions to Union veterans, encouraged the growth of railroads and homestead farming as their pitch to western voters, and had an increasingly vestigial interest in the idea that Black people living in the South should be allowed to vote. Cleveland beat them as what’s called a “Bourbon Democrat,” putting together a kind of classical liberal coalition that believed in lower tariffs, less spending, and no federal effort at civil rights enforcement, and also emphasized the idea that Republicans are corrupt.

Cleveland had an okay term but lost in 1888 to Benjamin Harrison, even while winning the popular vote. Then in 1892, Cleveland retook the White House. But the very next year, a major banking crisis generated financial panic and depression, resulting in a huge anti-Cleveland backlash in the 1894 midterms and, eventually, in Republicans gaining seats all up and down the ballot.

But if Republican gains were the primary impact of the anti-Cleveland backlash, a major secondary impact is that it helped Populists win a bunch of seats, especially in the South where the Republicans weren’t viable. To dramatically oversimplify, the Populists disagreed with the bipartisan consensus in favor of the Gold Standard and also had a lot of anti-business, anti-elite, pro-localism vibes — beyond the specific contours of the gold controversy — that echo to this day.1 The upshot of this, though, was that in 1896, Democrats abandoned Cleveland’s “Bourbon” approach and nominated William Jennings Bryan on an anti-gold platform, and Populist currents were just incorporated into mainstream Democratic Party politics. Similarly, it was much more common for self-identified progressives to win races as Democrats or Republicans, though the later Progressive Movement did spur some third party election wins. But the movement influenced both parties until FDR’s presidency decisively aligned progressive thought inside the New Deal coalition.

If American parties were more centralized and disciplined, the Bourbons would have retained control of the Democratic Party in a way that might have allowed an institutionally distinct People’s Party to emerge — perhaps bringing actual two-party politics to the Jim Crow South rather than the peculiar brand of factionalized one-party herrenvolk democracy that dominated the first half of the twentieth century.

Third parties today

I don’t really know what’s going to happen with RFK Jr. in the 2024 race, but it seems clear that his whole campaign is propped up by Trump donors hoping he’ll serve as an anti-Biden spoiler. This is actually so clear by now that it’s potentially backfiring, with Kennedy arguably mostly appealing to pissed off ex-Democrats whose second choice would be Trump.

Regardless, he’s not running to win, and he’s definitely not running to establish any kind of durable institution that would represent anyone or do anything.

And I think that’s the signature flaw of almost all recent third party politics. If you look back at Ralph Nader’s circa 2000 critique of the Democratic Party, those ideas have been pretty successful. But the success has come from conducting factional politics within the Democratic Party, to the point of Bernie Sanders mostly dropping the independent schtick and launching multiple Democratic Party primary bids.

Trying to create a genuine, institutionally distinct national party would be a lot of work compared to something like the RFK podcast tour, and it’s not obvious what the upside is. And I would say that moderate Democrats over the past 10-15 years have mostly suffered from a lack of factional organizing. Michael Bloomberg wore a bunch of different partisan hats over the course of his terms as Mayor of New York City, but his identity has always clearly been as a Democrat who has reformist ideas about urban governance. There are a bunch of people like that scattered across America’s cities, but there’s no broad network comparable to the Democratic Socialists of America or the Working Families Party that institutionalizes them.

WFP is an interesting model in this regard. They have “party” in the name, and in their home state of New York, they are organized as an actual political party. That’s because New York has a unique system of fusion voting in which a person can be the nominee of more than one party simultaneously, so WFP operates outside the institutional Democratic Party as a separate party that may or may not endorse the Democratic Party nominee. WFP organizers promote fusion voting in other states, but they haven’t waited on that to scale up — they just operate in other places as a factional left-wing organization. What I think is correct about that approach is that they firmly anchor on the importance of building an institutionalized network of candidates and elected officials, and then are flexible on the exact nature of that institution. Most third party efforts tend to start and end with a personality — Perot, Kennedy, whoever — or with the idea of a third party (No Labels) without ever committing to institutions.

The key thing, though, is that you can’t assume that dislike for the leadership of the two major parties will make people want to vote for an alternative. You need to think about opportunities to win races down ballot and build institutions that shift the parties themselves.

1 - my half joking solution to Columbus Day (the OG woke holiday made to recognize Italianx contributions to America) is to rename it Amerigo Vespucci day since he's a nice guy who made some maps and has the New World named after him

2 - CT also allows fusion voting and WFP also works with the state Democratic party on nominations

3 - I am going to re-up and slightly modify a comment made a few weeks back that was smacked around a bit because I used the word "breakup" in terms of the post-Trump GOP. It seems to me that the presidential competitiveness of the Trump GOP requires Trump's unique ability to activate low propensity voters and that no other GOP leader has that juice. Even if Trump wins this election I think there will be another election in 2028. I think the odds of a pretty nasty post-Trump reckoning within the GOP are high and they risk becoming more akin to the California GOP but at a national level. In California you have quasi-one party rule, but as we Borers know there's growing factions of YIMBY vs NIMBY, process vs results, etc. Is the future of American politics California? What happens if post-Trump the GOP realizes it just isn't competitive nationally? Or, how does the GOP emerge from Trump as a competitive party? What does that party look like?

I have thought for a while that the best way for a US third party would be to not jump into the high-profile, high-visibility presidential race where everyone has an incentive to punch on you left and right as a spoiler. Instead, you'd target specific seats in Congress that are winnable and only run there on a focussed agenda, then create a workable small coalition of high-leverage votes in Congress to drive that agenda (in a knife's edge majority like the current US house has, you'd effectively be a swing block). This would probably give you a high profile to drive the conversation, and you would basically build up the infrastructure over a decade before ever wading into a presidential race.

Why do both major US small parties (libertarian and green) struggle to break into the US house?