The hidden cause of cultural stagnation

Long copyrights incentivize IP management over creativity

Today’s post is from Chris Dalla Riva, who writes the newsletter Can’t Get Much Higher about the intersection of music and data, and whose book, “Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us About the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves,” is out now.

Everybody’s saying it: culture is stuck. Or at a standstill. Or collapsing. And it’s not just journalists and critics who talk like this. Surveys show regular people also think that popular culture is not doing well.

While I am skeptical of some of these ideas, people do have a decent point. The box office is jammed with prequels, sequels, and remakes. The highest grossing concert tours are often by artists from decades ago. Brand logos all look the same. Color is disappearing from the world.

Most people point to the internet, social media platforms, and curation algorithms as the causes of this stagnation, and I think there’s a lot of truth to those perspectives. But there’s a powerful force that is often left out of these discussions, one that is — ironically — meant to protect creatives: copyright. Let’s turn to the world of music, a world that I am very familiar with, to understand how.

The Music Catalog Purchasing Craze

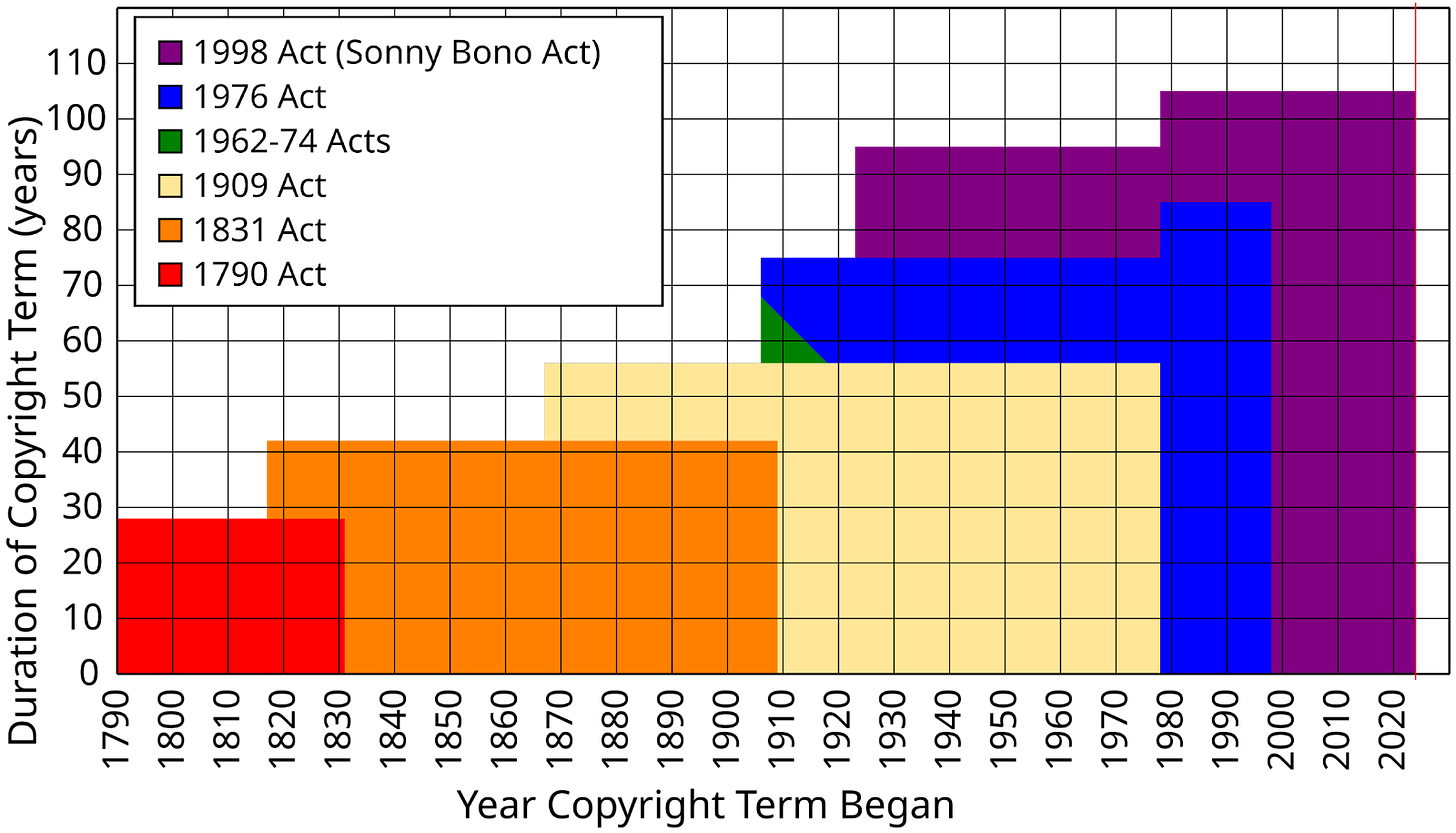

Copyright lasts a long time. Currently, works are protected in the United States for the life of the author plus 70 years for individual works and 95 years for anonymous works or works for hire. That means art can often remain valuable for more than a century, creating a huge incentive to buy up old copyrights and squeeze them for cash.

We see this happening right now. Over the last few years, labels, publishers, and private equity firms have been buying the catalogs of famous musicians for eye-popping sums. Neil Young sold his catalog to Hipgnosis Songs Fund for $150 million. Phil Collins and his Genesis bandmates sold theirs to Concord for $300 million. Bob Dylan also sold his to Universal for $300 million. Bruce Springsteen’s went to Sony for $550 million. And that only scratches the surface.

Why would anyone pay so much for a catalog of aging songs? It turns out there’s still a lot of money to be made on hits from decades ago. Billy Joel, for example, hasn’t released a studio album since 1993, yet he remains the 169th most popular artist on Spotify. Every time the Piano Man’s music is streamed, purchased, covered, or placed in the background of a movie or television show, he gets paid. Investors are betting that much music of the past will remain valuable long into the future.

Still, you can’t just sit on a music catalog for a hundred years and expect to rake in the dough. Popular culture changes fast. Most people aren’t listening to music from 1965, let alone 1925. If you want kids to be listening to “Yellow Submarine” 50 years from now, someone has to show it to them. Investors are aware of this, and that’s why they go to great lengths to remarket, repackage, and relitigate the past.

Remarket: Let’s Make a Movie!

In 2020, Authentic Brands Group was trying to reinvigorate Elvis Presley’s brand. After purchasing 85 percent of the King’s likeness, publishing, and estate in 2013, yearly earnings had fallen 30 percent. The company needed to make the “Heartbreak Hotel” singer cool again. Among other things, they decided to produce a new Elvis Presley biopic. The 2022 film, directed by Baz Luhrmann, grossed more than $280 million.

This Elvis Presley strategy has been played out repeatedly in the past decade.

Investment group purchases the intellectual property of a star from yesteryear

Investment group needs to create new revenue streams to turn a profit

Investment group produces a biopic

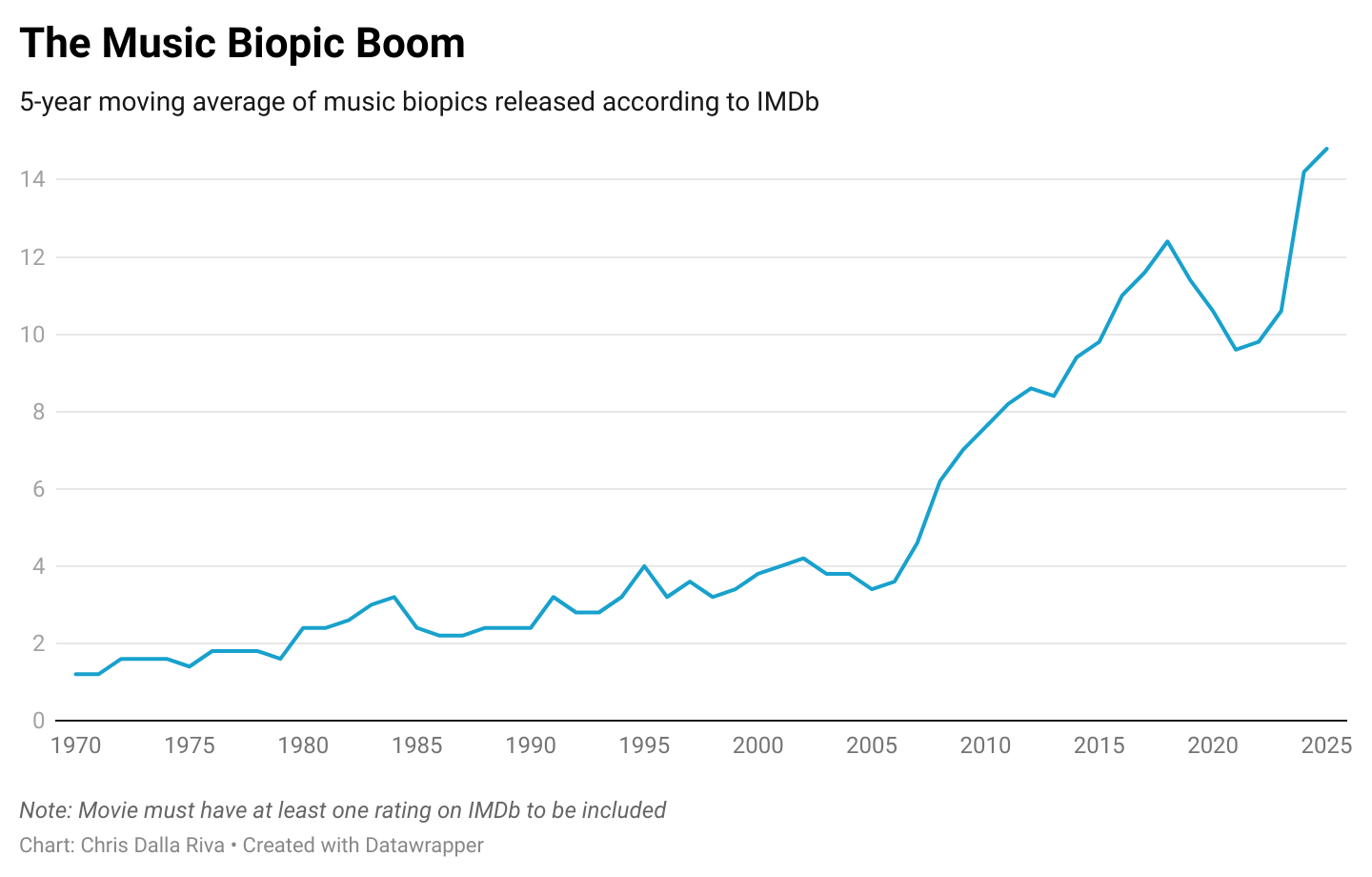

As I reported in my newsletter, we are seeing more than 200 percent more music biopics released each year on average as compared to just a few decades ago. Many of these biopics are released after the recent sale of intellectual property. As you might imagine, when gobs of money and resources are used to retell stories of the past, there is less of those things left for new stories.

Repackage: Let’s Make a Song!

In the same way that you may have noticed a surge in music biopics over the last decade, you may have also noticed huge hits sampling and interpolating elements of older hits. Shaboozey’s number one hit “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” interpolates large pieces of J-Kwon’s 2004 smash “Tipsy.” Jack Harlow’s number one hit “First Class” is built around a sample of Fergie’s 2006 number one hit “Glamorous.” Drake and Future’s “Way 2 Sexy” interpolates elements of Right Said Fred’s 1991 number one hit “I’m Too Sexy.”

Though sampling builds on a rich musical tradition, the reason some of these songs are created is the same reason modern biopics are created. In 2023, for example, Pitchfork reported that after Hipgnosis Songs Fund purchased the Rick James catalog, they began pitching A-listers on sampling “Super Freak.” Nicki Minaj and her team jumped at the offer and scored a smash with the bland “Super Freaky Girl.” Again, the promotion of songs like these come at the expense of novel ideas.

Relitigate: Let’s File a Lawsuit!

If remaking works of the past does not provide enough of a financial return, you can also just file a bunch of lawsuits. In 2019, the Wall Street Journal noted a 31 percent increase in musical copyright-infringement cases filed between 2015 and 2018. Many of those cases never make it very far, but litigation that goes the distance has increased too.

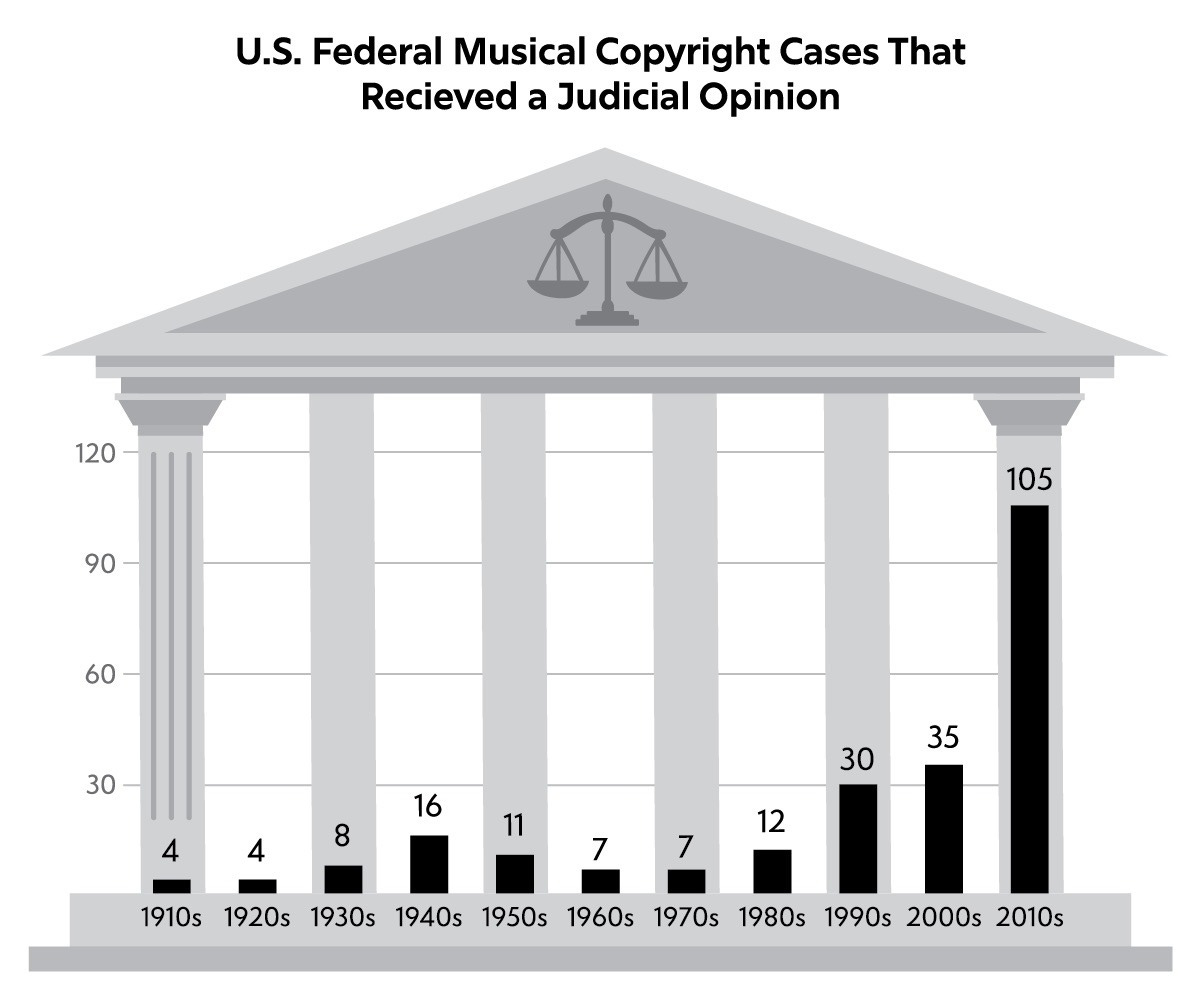

In my book “Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us About the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves,” I found that the number of musical copyright-infringement cases that received a judicial opinion at the federal level grew 200 percent between the 2000s and the 2010s.

Some of these lawsuits represent legitimate grievances. But most illustrate how exorbitant copyright terms allow the most successful rightsholders to bully the next generation of artists. The Marvin Gaye estate, for example, is notoriously litigious, suing anyone for so much as making music with a similar vibe as Mr. Gaye.

Of note, Marvin Gaye has been dead since 1984. Because his music won’t enter the public domain until 2054, his estate can try to maximize the return on his intellectual property by threatening — and often following through on — lawsuits. (Remixes and biopics also help, which the Gaye estate has been involved with in addition to their courtroom shenanigans.)

Of course, there’s nothing inherently wrong with trying to enforce your copyright in court. There’s nothing inherently wrong with making a music biopic. There’s also nothing inherently wrong with sampling and remixing older works. There isn’t even anything wrong with investing in intellectual property of the past.

But when you combine huge investments with digital platforms that make the past and present equally accessible, along with copyrights that will likely last more than a century, you get a situation where — as Pitchfork’s Marc Hogan put it in 2021 — “the handful of artists who struck it biggest in previous generations may cast an ever-larger shadow over the future.”

What Can We Do?

I don’t think we should abolish intellectual property rights. In fact, I think those rights are vital to the flourishing of creative industries. But our culture sits at a troubling intersection where creative tools are more accessible than ever before, but more money seems to be flowing into works of the past than works of the present. If copyright terms were shortened, there would be a stronger incentive to find the next generation of talent.

But how long should those terms be?

Sadly, we don’t have a ton of wiggle room. Copyright is largely governed by international treaties. The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works has been signed onto by 181 countries (including the US) and stipulates that the minimum term of protection should be at least the life of the author plus 50 years if the author is known and 50 years from publication if the author is unknown.

According to law professor Sam Ricketson, amending the terms of the Berne Convention is “highly unlikely,” so the best the U.S. may be able to do is adhere to the minimums. Even so, shortening from 95 years to 50 years, and life plus 70 years to life plus 50 years, would be a step in the right direction.

In the meantime, there are other tools that could help alleviate this issue. Some have suggested making it easier for authors to terminate their copyrights. Others have pushed for more clearly defining “transformative use,” which could cut down on frivolous litigation. Still, others have suggested lowering the caps for statutory damages in infringement cases.

While all of those would be helpful, I think the most impactful policy-fix would be the expansion of “compulsory licensing.”

Compulsory licenses allow a third party to use a protected work without the owner’s consent, provided royalties are paid to the owner. Not only does the Berne Convention lay out guidelines for compulsory licensing, but these licenses have been used to great effect in the U.S. and abroad.

In 1909, for example, Congress established a compulsory mechanical license in the world of music. This meant that if you wanted to cover, say, Bruce Springsteen’s “Dancing in the Dark,” you wouldn’t need express permission from the Boss. Anyone could release a cover of the song so long as they filed some paperwork and paid the government-mandated royalty rate.

Without the compulsory license, everyone — from the smallest artist to the biggest star — would need to get direct permission from the original songwriter and negotiate a royalty rate to perform a cover. This would have led to dramatically fewer covers being released. But because of compulsory licensing, musical interpretations flourished across a range of genres (e.g., jazz, blues, rock) during the 20th century with copyright owners still being compensated.

In other countries, compulsory licensing has also been established for “orphan works,” or those for which the author cannot be located. In these cases, governments have elected to step in and grant a limited, non-transferable license for a work. Compulsory licensing schemes could clearly be applied in a variety of artistic scenarios. In fact, I’ve previously advocated in Slow Boring for a compulsory license to be established for music samples.

This reasoning may strike you as odd. If Disney, for example, was forced to license various parts of the “Star Wars” universe to other creators, wouldn’t we just end up with an avalanche of horrible “Star War”-related content? Possibly. But because Disney has a monopoly on the idea, no one else can try to outdo them.

The compulsory license for cover songs again proves a good comparison here. There are scores of covers that are now considered the canonical version of a song. In a world without a compulsory license — or the public domain — it’s possible those would not exist (e.g., Jimi Hendrix covers Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower,” Jeff Buckley covers Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” Sinéad O’Connor covers Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U”).

Though we have largely focused this discussion around music, I want to make it clear that the same dynamics are playing out in nearly every creative industry. When film studios spend millions on legacy brands and old television series are rebooted and video game studios refuse to license out-of-print games, we are witnessing the same painful effects of long copyright terms in these fields.

There is no simple fix to make our culture more dynamic. But if we can advocate for any changes that prevent intellectual property from being weaponized, shorten the revenue runway for older works, and lower friction for the creation of newer works, then we might just create a world that incentivizes the creation of new works while still compensating the artists of yore.

Thank you to Adam Mastroianni for feedback on the post.

Thanks for featuring me! I love talking about how to make copyright work better for artists and think it’s an especially important issue in the age of AI.

I think the switch to streaming media has to be a big part of this discussion. Back in the olden days, if you really liked something, you bought the album. I've got CDs I bought as a kid in the 90s, the money changed hands back then, and that was that. Occasionally I dust one off and play it, but no further revenue is generated, they can't even harvest data that I did it for their algorithms. But with streaming, someone gets paid every time a song is played, no matter how old. This makes popular back catalogs very valuable.